PROTOCOL STUDY TITLE: Evaluation of Reading Speed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vision Screening Training

Vision Screening Training Child Health and Disability Prevention (CHDP) Program State of California CMS/CHDP Department of Health Care Services Revised 7/8/2013 Acknowledgements Vision Screening Training Workgroup – comprising Health Educators, Public Health Nurses, and CHDP Medical Consultants Dr. Selim Koseoglu, Pediatric Ophthalmologist Local CHDP Staff 2 Objectives By the end of the training, participants will be able to: Understand the basic anatomy of the eye and the pathway of vision Understand the importance of vision screening Recognize common vision disorders in children Identify the steps of vision screening Describe and implement the CHDP guidelines for referral and follow-up Properly document on the PM 160 vision screening results, referrals and follow-up 3 IMPORTANCE OF VISION SCREENING 4 Why Screen for Vision? Early diagnosis of: ◦ Refractive Errors (Nearsightedness, Farsightedness) ◦ Amblyopia (“lazy eye”) ◦ Strabismus (“crossed eyes”) Early intervention is the key to successful treatment 5 Why Screen for Vision? Vision problems often go undetected because: Young children may not realize they cannot see properly Many eye problems do not cause pain, therefore a child may not complain of discomfort Many eye problems may not be obvious, especially among young children The screening procedure may have been improperly performed 6 Screening vs. Diagnosis Screening Diagnosis 1. Identifies children at 1. Identifies the child’s risk for certain eye eye condition conditions or in need 2. Allows the eye of a professional -

Jaeger Eye Chart

Jaeger Eye Chart DIRECTIONS FOR USE The Jaeger eye chart (or Jaeger card) is used to test and document near visual acuity at a normal reading distance. Refractive errors and conditions that cause blurry reading vision include astigmatism, hyperopia (farsightedness) and presbyopia (loss of near focusing ability after age 40). If you typically wear eyeglasses or contact lenses full-time, you should wear them during the test. 1. Hold the test card 14 inches from the eyes. Use a tape measure to verify this distance. 2. The card should be illuminated with lighting typical of that used for comfortable reading. 3. Testing usually is performed with both eyes open; but if a significant difference between the two eyes is suspected, cover one eye and test each eye separately. 4. Go to the smallest block of text you feel you can see without squinting, and read that passage aloud. 5. Then try reading the next smaller block of text. (Remember: no squinting!) 6. Continue reading successively smaller blocks of print until you reach a size that is not legible. 7. Record the “J” value of the smallest block of text you can read (example: “J1”). DISCLAIMER: Eye charts measure only visual acuity, which is just one component of good vision. They cannot determine if your eyes are “working overtime” (needing to focus more than normal, which can lead to headaches and eye strain). Nor can they determine if your eyes work properly as a team for clear, comfortable binocular vision and accurate depth perception. Eye charts also cannot detect serious eye problems such as glaucoma or early diabetic retinopathy that could lead to serious vision impairment and even blindness. -

AAO 2018 2019 BCSC Sectio

The American Academy of Ophthalmology is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) to provide continuing medical education for physicians. The American Academy of Ophthalmology designates this enduring material for a maximum of 15 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity. CME expiration date: June 1, 2021. AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ may be claimed only once between June 1, 2018, and the expiration date. BCSC® volumes are designed to increase the physician’s ophthalmic knowledge through study and review. Users of this activity are encouraged to read the text and then answer the study questions provided at the back of the book. To claim AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ upon completion of this activity, learners must demonstrate appropriate knowledge and participation in the activity by taking the posttest for Section 3 and achieving a score of 80% or higher. For further details, please see the instructions for requesting CME credit at the back of the book. The Academy provides this material for educational purposes only. It is not intended to represent the only or best method or procedure in every case, nor to replace a physician’s own judgment or give specic advice for case management. Including all indications, contraindications, side eects, and alternative agents for each drug or treatment is beyond the scope of this material. All information and recommendations should be veried, prior to use, with current information included in the manufacturers’ package inserts or other independent sources, and considered in light of the patient’s condition and history. -

Screening for Visual Impairment in Children Ages 1–5 Years: Update for the USPSTF

Screening for Visual Impairment in Children Ages 1–5 Years: Update for the USPSTF AUTHORS: Roger Chou, MD,a,b,c Tracy Dana, MLS,a and abstract Christina Bougatsos, BSa CONTEXT: Screening could identify preschool-aged children with vi- aOregon Evidence-Based Practice Center and Departments of bMedicine and cMedical Informatics and Clinical Epidemiology, sion problems at a critical period of visual development and lead to Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon treatments that could improve vision. KEY WORDS OBJECTIVE: To determine the effectiveness of screening preschool- impaired visual acuity, vision screening, vision tests, preschool aged children for impaired visual acuity on health outcomes. children, refractive errors, amblyopia, amblyogenic risk factors, random dot E stereoacuity test, MTI photoscreener, patching, METHODS: We searched Medline from 1950 to July 2009 and the Co- systematic review chrane Library through the third quarter of 2009, reviewed reference ABBREVIATIONS lists, and consulted experts. We selected randomized trials and con- USPSTF—US Preventive Services Task Force trolled observational studies on preschool vision screening and treat- logMAR—logarithmic minimal angle of resolution ALSPAC—Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children ments, and studies of diagnostic accuracy of screening tests. One in- RR—relative risk vestigator abstracted relevant data, and a second investigator CI—confidence interval checked data abstraction and quality assessments. VIP—Vision in Preschoolers PLR—positive likelihood ratio RESULTS: Direct evidence on the effectiveness of preschool vision NLR—negative likelihood ratio screening for improving visual acuity or other clinical outcomes re- MTI—Medical Technology and Innovations OR—odds ratio mains limited and does not adequately address whether screening is D—diopter(s) more effective than no screening. -

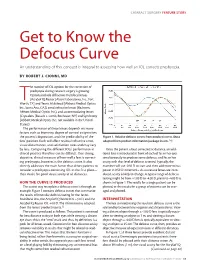

Get to Know the Defocus Curve an Understanding of This Concept Is Integral to Assessing How Well an IOL Corrects Presbyopia

CATARACT SURGERY FEATURE STORY Get to Know the Defocus Curve An understanding of this concept is integral to assessing how well an IOL corrects presbyopia. BY ROBERT J. CIONNI, MD he number of IOL options for the correction of presbyopia during cataract surgery is growing. Options include diffractive multifocal lenses (AcrySof IQ Restor [Alcon Laboratories, Inc., Fort TWorth, TX] and Tecnis Multifocal [Abbott Medical Optics Inc., Santa Ana, CA]), zonal refractive lenses (ReZoom; Abbott Medical Optics Inc.), and accommodating lenses (Crystalens [Bausch + Lomb, Rochester, NY] and Synchrony [Abbott Medical Optics Inc.; not available in the United States]). The performance of these lenses depends on many factors such as biometry, degree of corneal astigmatism, the patient’s disposition, and the predictability of the Figure 1. Relative defocus curves from product inserts. (Data lens’ position. Each will affect residual refractive error, adapted from product information/package inserts.1,2) visual disturbances, and satisfaction rates and may vary by lens. Comparing the different IOLs’ performance in Once the patient is best corrected at distance, an addi- clinical practice therefore can be difficult. One strong, tional lens is introduced in front of each of his or her eyes objective, clinical measure of how well a lens is correct- simultaneously to produce some defocus, and his or her ing presbyopia, however, is the defocus curve. It also acuity with that level of defocus is tested. Typically, the directly addresses the main factor that drives patients to examiner will use -0.50 D to start and then add more minus consider a presbyopia-correcting IOL in the first place— power in 0.50 D increments. -

Your Source Vision

Good-Lite Product Catalog YOUR SOURCE for VISION Cognitive Test • Grating Acuity • Wall Charts • Handheld Charts • EyeSpy 20/20 • 10x18 Charts • ETDRS Charts • Low Vision • Intermediate Vision • Near Vision • Read- ing Cards • ETDRS Cabinet • Spot Vision Screener • ESV1200 - 9x14 • ESV1018 - 10x18 • Insta-Line • CSV-1000 • Super Pinhole • Accessories • Screening Software • Testing Software • Fixation • Occluders • Fun Frames • Prisms • Hyperopia • Retinoscopy • Eye Models • Stereo Test • Worth 4-Dot • Color Books & Tests • D15 Style Color Test • Desaturated 1-800-263-3557 Color Test • Projector Slides • Continuous Text • Adult Charts • Children Charts • Pediatric Charts • Vectographic Slides • Amsler Grid • Campimeter • Prism Bar • Loose Prism • Spanish • Vectograph • Maddox • Cylinders • Phoropter • Trial Lens/Frames • Filters • Risley • Eye PatchesGOOD-LITE • LEA Symbols • LEA Numbers • Contrast Sensitivity • Visual Field • Cognitive Vision • Adaptation • Color Vision • Optokinetic • Tangent Screen • Flat & Curved Prism • Magnifier • Flipper • Slit Lamp Celebrating More Than 80 Years of Good-Lite The Good-Lite Company is celebrating In the 1970s, Palmer worked with Otto in children and adults with developmental more than 80 years as the industry leader Lippmann, MD, to develop HOTV optotypes delays/disabilities. The American Academy of in illuminated cabinets; evidence-based eye using Sloan letters. Lippmann’s HOTV Pediatrics, et al., includes LEA Symbols on its charts, such as the LEA Symbols, and many optotypes — a modified version of a Stycar list of recommended tests for preschool vision more vision screening and testing products matching letters test based on Snellen screening. available in this catalog and online. letters — are useful for screening and testing Good-Lite values its key role in helping vision The combined efforts of Robert Good, vision of children as young as age 3 years. -

Fonts Designed for Macular Degeneration: Impact on Reading

Low Vision Fonts Designed for Macular Degeneration: Impact on Reading Ying-Zi Xiong,1 Ethan A. Lorsung,1 John Stephen Mansfield,2 Charles Bigelow,3 and Gordon E. Legge1 1Department of Psychology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States 2Department of Psychology, State University of New York at Plattsburgh, Plattsburgh, New York, United States 3Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester, New York, United States Correspondence: Ying-Zi Xiong, De- PURPOSE. People with macular degeneration (MD) experience difficulties in reading due to partment of Psychology, University central-field loss. Two new fonts, Eido and Maxular Rx, have been designed specifically for of Minnesota, No. 79 East River Road individuals with MD. We have compared reading performance of these new fonts with three S219, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA; mainstream fonts (Times-Roman, Courier, and Helvetica). [email protected]. METHODS. Subjects with MD ( 19) and normally sighted subjects ( 40) were tested with Submitted: March 17, 2018 n ¼ n ¼ Accepted: July 15, 2018 digital versions of the MNREAD test using the five fonts. Maximum reading speed (MRS), critical print size (CPS), and reading acuity (RA) were estimated to characterize reading Citation: Xiong Y-Z, Lorsung EA, performance. Physical properties of the fonts were quantified by interletter spacing and Mansfield JS, Bigelow C, Legge GE. perimetric complexity. Fonts designed for macular degenera- tion: impact on reading. Invest Oph- RESULTS. Reading with MD showed font differences in MRS, CPS, and RA. Compared with thalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59:4182–4189. Helvetica and Times, Maxular Rx permitted both smaller CPS and RA, and Eido permitted https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.18-24334 smaller RA. -

Glaucoma Eye Examination Checklist

Glaucoma Eye Examination Checklist Glaucoma is an eye disease that causes irreversible loss of vision, and there are no symptoms until the advanced stages. Glaucoma New Zealand recommends that everyone, even people without symptoms of any eye problem, should have an examination to check for glaucoma by the time they are 45. If the exam is normal, then you should have a repeat glaucoma eye examination at least every five years. However, if you have a family history of glaucoma, or have other risk factors for developing glaucoma, then you may need to be seen at a younger age and followed up more regularly. As part of an eye examination to check for glaucoma, your optometrist or ophthalmologist should check the following: • You will be asked questions about your previous eye health, including any medications you may have taken for eye conditions, and any history of eye injury or surgery. • You will be asked about any family history of glaucoma and other eye diseases. • You will be asked about your general health, and about the medications you are currently taking or have taken in the past, particularly steroid medications. Some health conditions are associated with an increased risk of glaucoma. • Your focusing error will be assessed. People with high levels of focusing error are at increased risk of developing glaucoma. For example, people who are highly short- sighted are at higher risk of developing open angle glaucoma, and people who are very long-sighted have a higher risk of narrow angles and angle closure glaucoma. • You will be asked to read the smallest letters you can see on an eye chart. -

CHDP Pediatric Vision Screening

CHDP Pediatric Vision Screening Child Health and Disability Prevention (CHDP ) Program Systems of Care Division (SCD) California Department of Health Care Services 7/14/2017 1 Learning Objectives • Understand the importance of vision screening during childhood. • Become aware of eye problems that affect vision. • Describe and implement the CHDP program guidelines for referral and follow-up. • Identify the steps of vision screening and document results. 7/14/2017 2 Why Perform Vision Screening? • Recommended as part of the American Academy of Pediatrics Bright Futures Periodicity Schedule • For ages where risk assessment is required, see Bright Futures Pre-visit Questionnaire – Available in all ages 7/14/2017 3 Bright Futures Pre-Visit Questionnaire for 7-year-old 7/14/2017 4 Why Perform Vision Screening? • Primary Care Physicians and Nurses: – The first line of defense to detect preventable vision loss in children • Early detection of amblyopia - “lazy eye” – Leading cause of vision loss among children 7/14/2017 5 Amblyopia • Amblyopia is the leading cause of vision loss among children. • Eyes and brain are not working together. • One eye sees a blurred view and the other a normal view. The brain only processes the normal view. 7/14/2017 6 Amblyopia Amblyopia can only develop during childhood. • If not treated in childhood, amblyopia may result in permanent vision loss. • The most common cause of vision loss in adults 20-70 years of age is untreated childhood amblyopia. 7/14/2017 7 Amblyopia • Common causes are: – Untreated or unequal refractive errors (nearsighted, farsighted, astigmatism) – Strabismus “crossed eyes” – Obstruction (e.g. ptosis, cataract) 7/14/2017 8 Common Causes of Amblyopia 1. -

Guidelines for School Vision Screening Programs: Kindergarten Through Grade12

Guidelines for School Vision Screening Programs: Kindergarten through Grade12 Colorado Department of Education January 2006 Preface The guidelines in this manual have been revised from the Guidelines for School Vision Screening Programs, September 1991, 2nd Edition.1 Recommendations for the updated guidelines are based on C.R.S. 22-1-116 and the National Association of School Nurses, To See or Not To See: Screening the Vision of Children in School, by Susan Proctor2. Standardization of school vision screening programs is lacking according to Susan Proctor (2005). Areas of needed remediation noted are (1) methodology, (2) frequency of screening, (3) visual functions assessed, and (4) criteria for referral. There remain no clinical standards for schools and children in school programs endorsed by, developed by, and disseminated to, all professionals interested and affected, including nurses, which recommend specific criteria to be employed in school screening programs for children of all ages. 3 In her book Susan Proctor references several researchers who have commented on the need for more standardization in the screening process.4 There remains a void in clear and cogent direction for comprehensive school screening parameters for persons from birth through age 22, which is the population range served by contemporary public schools. The intent of the revised Colorado Vision Screening Guidelines is to identify the tests and appropriate equipment to use for an optimal screening program as recommended by the latest research. These guidelines will continue to be amended and updated as new research and methodology evolve. 1 Colorado Department of Public Health & Environment (1991). Guidelines for school vision screening programs. -

Refractive Error & Visual Acuity

Refractive Error & Visual Acuity What is refractive error? Refractive error occurs when the eye is unable to focus light because it does not fall properly on the retina, causing vision to be blurry. For clear vision, light rays reflecting from an object need to fall directly onto the macula (the central part of the retina) in the back of the eye. The different parts of the eye and the length of the eye determines if the light rays focus on the back of the eye – this includes the cornea (the clear front surface of the eye), the lens (helps to bend the light toward the retina), and the liquid inside the eye (aqueous humor and vitreous). If the light does not focus on the retina, then blurry vision will result and this blurred vision is called refractive error. What are the types of refractive errors? Myopia (Nearsightedness): Myopia occurs when the eyeball is too long for light rays to focus properly on the retina. As a result, images of distant objects, such as road signs, appear blurred. Hyperopia (Farsightedness): Hyperopia occurs when the eyeball is too short for light rays to focus properly on the retina. As a result of moderate amounts of hyperopia, images of near objects, such as a text on a smartphone, appear blurred. Astigmatism: Astigmatism occurs primarily from an irregular shape of the front surface of the cornea at the front of the eye. In astigmatism, the cornea tends to be shaped more like a football instead of a basketball, and this difference in shape causes light rays to scatter across the retina instead of focusing properly on the retina. -

Banner Eye Care Visual Acuity Test 2.0 This Page Is ANSI Letter Sized (8.5”X11”)

Guide to In-Home Vision Testing Banner Eye Care How to set up the tests • This PDF document contains the following vision tests and instructions: • Letter Distance Chart: This is a common eye chart. This chart can be used with children who know all their letters and with adults who read. It assumes that people are literate, and can say the letters one at a time. • HOTV Distance Chart: This is a letter chart that is used with young children who are unsure of their letters, or for those who do not read. Instead of saying the letters on the chart, a helper points to letters on the HOTV Distance Chart one letter at a time, and the person being tested points to the matching letter on the HOTV Pointing Card. • Reading and HOTV Near Charts: This is used for testing vision close-up. Charts to test the ability to read words or match letters are provided. • Macular Function Chart: This chart contains the Amsler Grid that is used to detect vision problems resulting from damage to the retina (the inner surface of the back of the eye). • If you have a printer, print the individual pages for the charts you would like to use (shown below). • If you do not have a printer, the tests can be displayed on a computer screen either with Acrobat Reader, or as pictures. • Once you have a test printed or displayed on a computer screen, please check the image of the quarter, and compare it to an actual quarter. They should be the same size (1 inch, or 25 mm, across).