The Effect of Concentration on Rate – Student Sheet to Study to Discuss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Change and Human Health: Risks and Responses

Climate change and human health RISKS AND RESPONSES Editors A.J. McMichael The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia D.H. Campbell-Lendrum London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom C.F. Corvalán World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland K.L. Ebi World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, European Centre for Environment and Health, Rome, Italy A.K. Githeko Kenya Medical Research Institute, Kisumu, Kenya J.D. Scheraga US Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, USA A. Woodward University of Otago, Wellington, New Zealand WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION GENEVA 2003 WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Climate change and human health : risks and responses / editors : A. J. McMichael . [et al.] 1.Climate 2.Greenhouse effect 3.Natural disasters 4.Disease transmission 5.Ultraviolet rays—adverse effects 6.Risk assessment I.McMichael, Anthony J. ISBN 92 4 156248 X (NLM classification: WA 30) ©World Health Organization 2003 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from Marketing and Dis- semination, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel: +41 22 791 2476; fax: +41 22 791 4857; email: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications—whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution—should be addressed to Publications, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; email: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Atomic Layer Deposition on Dispersed Materials in Liquid Phase by Stoichiometrically Limited Injections

COMMUNICATION www.advmat.de Atomic Layer Deposition on Dispersed Materials in Liquid Phase by Stoichiometrically Limited Injections Benjamin P. Le Monnier, Frederick Wells, Farzaneh Talebkeikhah, and Jeremy S. Luterbacher* deposition.[2] Since then, processes for Atomic layer deposition (ALD) is a well-established vapor-phase technique depositing a range of materials including for depositing thin films with high conformality and atomically precise oxides, nitrides, hybrids and even metals [3–5] control over thickness. Its industrial development has been largely confined have been developed. This wide to wafers and low-surface-area materials because deposition on high-surface- variety of materials combined with its atomic-level precision has made ALD area materials and powders remains extremely challenging. Challenges with a formidable tool for the fabrication of such materials include long deposition times, extensive purging cycles, and nanostructured materials such as transis- requirements for large excesses of precursors and expensive low-pressure tors, solar cells and fuel cells.[6] equipment. Here, a simple solution-phase deposition process based on More recently, processes have been subsequent injections of stoichiometric quantities of precursor is performed developed to apply ALD to high-surface- area materials (>10 m2 g−1), including using common laboratory synthesis equipment. Precisely measured precursor powders for various applications, from stoichiometries avoid any unwanted reactions in solution and ensure layer-by- passivation of photoactive material to cata- layer growth with the same precision as gas-phase ALD, without any excess lyst preparation.[7,8] With such materials, precursor or purging required. Identical coating qualities are achieved when long exposure time (minutes vs millisec- onds for wafers), both for purge and reac- comparing this technique to Al2O3 deposition by fluidized-bed reactor ALD tion cycles, must be coupled with effec- (FBR-ALD). -

Chapter 12 Lecture Notes

Chemical Kinetics “The study of speeds of reactions and the nanoscale pathways or rearrangements by which atoms and molecules are transformed to products” Chapter 13: Chemical Kinetics: Rates of Reactions © 2008 Brooks/Cole 1 © 2008 Brooks/Cole 2 Reaction Rate Reaction Rate Combustion of Fe(s) powder: © 2008 Brooks/Cole 3 © 2008 Brooks/Cole 4 Reaction Rate Reaction Rate + Change in [reactant] or [product] per unit time. Average rate of the Cv reaction can be calculated: Time, t [Cv+] Average rate + Cresol violet (Cv ; a dye) decomposes in NaOH(aq): (s) (mol / L) (mol L-1 s-1) 0.0 5.000 x 10-5 13.2 x 10-7 10.0 3.680 x 10-5 9.70 x 10-7 20.0 2.710 x 10-5 7.20 x 10-7 30.0 1.990 x 10-5 5.30 x 10-7 40.0 1.460 x 10-5 3.82 x 10-7 + - 50.0 1.078 x 10-5 Cv (aq) + OH (aq) → CvOH(aq) 2.85 x 10-7 60.0 0.793 x 10-5 -7 + + -5 1.82 x 10 change in concentration of Cv Δ [Cv ] 80.0 0.429 x 10 rate = = 0.99 x 10-7 elapsed time Δt 100.0 0.232 x 10-5 © 2008 Brooks/Cole 5 © 2008 Brooks/Cole 6 1 Reaction Rates and Stoichiometry Reaction Rates and Stoichiometry Cv+(aq) + OH-(aq) → CvOH(aq) For any general reaction: a A + b B c C + d D Stoichiometry: The overall rate of reaction is: Loss of 1 Cv+ → Gain of 1 CvOH Rate of Cv+ loss = Rate of CvOH gain 1 Δ[A] 1 Δ[B] 1 Δ[C] 1 Δ[D] Rate = − = − = + = + Another example: a Δt b Δt c Δt d Δt 2 N2O5(g) 4 NO2(g) + O2(g) Reactants decrease with time. -

Andrea Deoudes, Kinetics: a Clock Reaction

A Kinetics Experiment The Rate of a Chemical Reaction: A Clock Reaction Andrea Deoudes February 2, 2010 Introduction: The rates of chemical reactions and the ability to control those rates are crucial aspects of life. Chemical kinetics is the study of the rates at which chemical reactions occur, the factors that affect the speed of reactions, and the mechanisms by which reactions proceed. The reaction rate depends on the reactants, the concentrations of the reactants, the temperature at which the reaction takes place, and any catalysts or inhibitors that affect the reaction. If a chemical reaction has a fast rate, a large portion of the molecules react to form products in a given time period. If a chemical reaction has a slow rate, a small portion of molecules react to form products in a given time period. This experiment studied the kinetics of a reaction between an iodide ion (I-1) and a -2 -1 -2 -2 peroxydisulfate ion (S2O8 ) in the first reaction: 2I + S2O8 I2 + 2SO4 . This is a relatively slow reaction. The reaction rate is dependent on the concentrations of the reactants, following -1 m -2 n the rate law: Rate = k[I ] [S2O8 ] . In order to study the kinetics of this reaction, or any reaction, there must be an experimental way to measure the concentration of at least one of the reactants or products as a function of time. -2 -2 -1 This was done in this experiment using a second reaction, 2S2O3 + I2 S4O6 + 2I , which occurred simultaneously with the reaction under investigation. Adding starch to the mixture -2 allowed the S2O3 of the second reaction to act as a built in “clock;” the mixture turned blue -2 -2 when all of the S2O3 had been consumed. -

SF Chemical Kinetics. Microscopic Theories of Chemical Reaction Kinetics

SF Chemical Kinetics. Lecture 5. Microscopic theory of chemical reaction kinetics. Microscopic theories of chemical reaction kinetics. • A basic aim is to calculate the rate constant for a chemical reaction from first principles using fundamental physics. • Any microscopic level theory of chemical reaction kinetics must result in the derivation of an expression for the rate constant that is consistent with the empirical Arrhenius equation. • A microscopic model should furthermore provide a reasonable interpretation of the pre-exponential factor A and the activation energy EA in the Arrhenius equation. • We will examine two microscopic models for chemical reactions : – The collision theory. – The activated complex theory. • The main emphasis will be on gas phase bimolecular reactions since reactions in the gas phase are the most simple reaction types. 1 References for Microscopic Theory of Reaction Rates. • Effect of temperature on reaction rate. – Burrows et al Chemistry3, Section 8. 7, pp. 383-389. • Collision Theory/ Activated Complex Theory. – Burrows et al Chemistry3, Section 8.8, pp.390-395. – Atkins, de Paula, Physical Chemistry 9th edition, Chapter 22, Reaction Dynamics. Section. 22.1, pp.832-838. – Atkins, de Paula, Physical Chemistry 9th edition, Chapter 22, Section.22.4-22.5, pp. 843-850. Collision theory of bimolecular gas phase reactions. • We focus attention on gas phase reactions and assume that chemical reactivity is due to collisions between molecules. • The theoretical approach is based on the kinetic theory of gases. • Molecules are assumed to be hard structureless spheres. Hence the model neglects the discrete chemical structure of an individual molecule. This assumption is unrealistic. • We also assume that no interaction between molecules until contact. -

Ochem ACS Review 23 Aryl Halides

ACS Review Aryl Halides 1. Which one of the following has the weakest carbon-chlorine bond? A. I B. II C. III D. IV 2. Which compound in each of the following pairs is the most reactive to the conditions indicated? A. I and III B. I and IV C. II and III D. II and IV 3. Which of the following reacts at the fastest rate with potassium methoxide (KOCH 3) in methanol? A. fluorobenzene B. 4-nitrofluorobenzene C. 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene D. 2,4,6-trinitrofluorobenzene 4. Which of the following reacts at the fastest rate with potassium methoxide (KOCH 3) in methanol? A. fluorobenzene B. p-nitrofluorobenzene C. p-fluorotoluene D. p-bromofluorobenzene 5. Which of the following is the kinetic rate equation for the addition-elimination mechanism of nucleophilic aromatic substitution? A. rate = k[aryl halide] B. rate = k[nucleophile] C. rate = k[aryl halide][nucleophile] D. rate = k[aryl halide][nucleophile] 2 6. Which of the following is not a resonance form of the intermediate in the nucleophilic addition of hydroxide ion to para -fluoronitrobenzene? A. I B. II C. III D. IV 7. Which chlorine is most susceptible to nucleophilic substitution with NaOCH 3 in methanol? A. #1 B. #2 C. #1 and #2 are equally susceptible D. no substitution is possible 8. What is the product of the following reaction? A. N,N-dimethylaniline B. para -chloro-N,N-dimethylaniline C. phenyllithium (C 6H5Li) D. meta -chloro-N,N-dimethylaniline 9. Which one of the reagents readily reacts with bromobenzene without heating? A. -

Department of Chemistry

07 Sept 2020 2020–2021 Module Outlines MSc Chemistry MSc Chemistry with Medicinal Chemistry Please note: This handbook contains outlines for the modules comprise the lecture courses for all the MSc Chemistry and Chemistry with Medicinal Chemistry courses. The outline is also posted on Moodle for each lecture module. If there are any updates to these published outlines, this will be posted on the Level 4 Moodle, showing the date, to indicate that there has been an update. PGT CLASS HEAD: Dr Stephen Sproules, Room A5-14 Phone (direct):0141-330-3719 email: [email protected] LEVEL 4 CLASS HEAD: Dr Linnea Soler, Room A4-36 Phone (direct):0141-330-5345 email: [email protected] COURSE SECRETARY: Mrs Susan Lumgair, Room A4-30 (Teaching Office) Phone: 0141-330-3243 email: [email protected] TEACHING ADMINISTRATOR: Ms Angela Woolton, Room A4-27 (near Teaching Office) Phone: 0141-330-7704 email: [email protected] Module Topics for Lecture Courses The Course Information Table below shows, for each of the courses (e.g. Organic, Inorganic, etc), the lecture modules and associated lecturer. Chemistry with Medicinal Chemistry students take modules marked # in place of modules marked ¶. Organic Organic Course Modules Lecturer Chem (o) o1 Pericyclic Reactions Dr Sutherland o2 Heterocyclic Systems Dr Boyer o3 Advanced Organic Synthesis Dr Prunet o4 Polymer Chemistry Dr Schmidt o5m Asymmetric Synthesis Prof Clark o6m Organic Materials Dr Draper Inorganic Inorganic Course Modules Lecturer Chem (i) i1 Metals in Medicine -

Reaction Kinetics in Organic Reactions

Autumn 2004 Reaction Kinetics in Organic Reactions Why are kinetic analyses important? • Consider two classic examples in asymmetric catalysis: geraniol epoxidation 5-10% Ti(O-i-C3H7)4 O DET OH * * OH + TBHP CH2Cl2 3A mol sieve OH COOH5C2 L-(+)-DET = OH COOH5C2 * OH geraniol hydrogenation OH 0.1% Ru(II)-BINAP + H2 CH3OH P(C6H5)2 (S)-BINAP = P(C6 H5)2 • In both cases, high enantioselectivities may be achieved. However, there are fundamental differences between these two reactions which kinetics can inform us about. 1 Autumn 2004 Kinetics of Asymmetric Catalytic Reactions geraniol epoxidation: • enantioselectivity is controlled primarily by the preferred mode of initial binding of the prochiral substrate and, therefore, the relative stability of intermediate species. The transition state resembles the intermediate species. Finn and Sharpless in Asymmetric Synthesis, Morrison, J.D., ed., Academic Press: New York, 1986, v. 5, p. 247. geraniol hydrogenation: • enantioselectivity may be dictated by the relative reactivity rather than the stability of the intermediate species. The transition state may not resemble the intermediate species. for example, hydrogenation of enamides using Rh+(dipamp) studied by Landis and Halpern (JACS, 1987, 109,1746) 2 Autumn 2004 Kinetics of Asymmetric Catalytic Reactions “Asymmetric catalysis is four-dimensional chemistry. Simple stereochemical scrutiny of the substrate or reagent is not enough. The high efficiency that these reactions provide can only be achieved through a combination of both an ideal three-dimensional structure (x,y,z) and suitable kinetics (t).” R. Noyori, Asymmetric Catalysis in Organic Synthesis,Wiley-Interscience: New York, 1994, p.3. “Studying the photograph of a racehorse cannot tell you how fast it can run.” J. -

Enzymatic Kinetic Isotope Effects from First-Principles Path Sampling

Article pubs.acs.org/JCTC Enzymatic Kinetic Isotope Effects from First-Principles Path Sampling Calculations Matthew J. Varga and Steven D. Schwartz* Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721, United States *S Supporting Information ABSTRACT: In this study, we develop and test a method to determine the rate of particle transfer and kinetic isotope effects in enzymatic reactions, specifically yeast alcohol dehydrogenase (YADH), from first-principles. Transition path sampling (TPS) and normal mode centroid dynamics (CMD) are used to simulate these enzymatic reactions without knowledge of their reaction coordinates and with the inclusion of quantum effects, such as zero-point energy and tunneling, on the transferring particle. Though previous studies have used TPS to calculate reaction rate constants in various model and real systems, it has not been applied to a system as large as YADH. The calculated primary H/D kinetic isotope effect agrees with previously reported experimental results, within experimental error. The kinetic isotope effects calculated with this method correspond to the kinetic isotope effect of the transfer event itself. The results reported here show that the kinetic isotope effects calculated from first-principles, purely for barrier passage, can be used to predict experimental kinetic isotope effects in enzymatic systems. ■ INTRODUCTION staging method from the Chandler group.10 Another method that uses an energy gap formalism like QCP is a hybrid Particle transfer plays a crucial role in a breadth of enzymatic ff reactions, including hydride, hydrogen atom, electron, and quantum-classical approach of Hammes-Schi er and co-work- 1 ers, which models the transferring particle nucleus as a proton-coupled electron transfer reactions. -

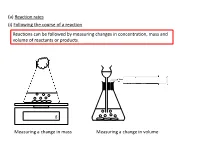

(A) Reaction Rates (I) Following the Course of a Reaction Reactions Can Be Followed by Measuring Changes in Concentration, Mass and Volume of Reactants Or Products

(a) Reaction rates (i) Following the course of a reaction Reactions can be followed by measuring changes in concentration, mass and volume of reactants or products. g Measuring a change in mass Measuring a change in volume Volume of gas produced of gas Volume Mass of beaker and contents of beaker Mass Time Time The rate is highest at the start of the reaction because the concentration of reactants is highest at this point. The steepness (gradient) of the plotted line indicates the rate of the reaction. We can also measure changes in product concentration using a pH meter for reactions involving acids or alkalis, or by taking small samples and analysing them by titration or spectrophotometry. Concentration reactant Time Calculating the average rate The average rate of a reaction, or stage in a reaction, can be calculated from initial and final quantities and the time interval. change in measured factor Average rate = change in time Units of rate The unit of rate is simply the unit in which the quantity of substance is measured divided by the unit of time used. Using the accepted notation, ‘divided by’ is represented by unit-1. For example, a change in volume measured in cm3 over a time measured in minutes would give a rate with the units cm3min-1. 0.05-0.00 Rate = 50-0 1 - 0.05 = 50 = 0.001moll-1s-1 Concentration moll Concentration 0.075-0.05 Rate = 100-50 0.025 = 50 = 0.0005moll-1s-1 The rate of a reaction, or stage in a reaction, is proportional to the reciprocal of the time taken. -

Kinetics 651

Chapter 12 | Kinetics 651 Chapter 12 Kinetics Figure 12.1 An agama lizard basks in the sun. As its body warms, the chemical reactions of its metabolism speed up. Chapter Outline 12.1 Chemical Reaction Rates 12.2 Factors Affecting Reaction Rates 12.3 Rate Laws 12.4 Integrated Rate Laws 12.5 Collision Theory 12.6 Reaction Mechanisms 12.7 Catalysis Introduction The lizard in the photograph is not simply enjoying the sunshine or working on its tan. The heat from the sun’s rays is critical to the lizard’s survival. A warm lizard can move faster than a cold one because the chemical reactions that allow its muscles to move occur more rapidly at higher temperatures. In the absence of warmth, the lizard is an easy meal for predators. From baking a cake to determining the useful lifespan of a bridge, rates of chemical reactions play important roles in our understanding of processes that involve chemical changes. When planning to run a chemical reaction, we should ask at least two questions. The first is: “Will the reaction produce the desired products in useful quantities?” The second question is: “How rapidly will the reaction occur?” A reaction that takes 50 years to produce a product is about as useful as one that never gives a product at all. A third question is often asked when investigating reactions in greater detail: “What specific molecular-level processes take place as the reaction occurs?” Knowing the answer to this question is of practical importance when the yield or rate of a reaction needs to be controlled. -

S.T.E.T.Women's College, Mannargudi Semester Iii Ii M

S.T.E.T.WOMEN’S COLLEGE, MANNARGUDI SEMESTER III II M.Sc., CHEMISTRY ORGANIC CHEMISTRY - II – P16CH31 UNIT I Aliphatic nucleophilic substitution – mechanisms – SN1, SN2, SNi – ion-pair in SN1 mechanisms – neighbouring group participation, non-classical carbocations – substitutions at allylic and vinylic carbons. Reactivity – effect of structure, nucleophile, leaving group and stereochemical factors – correlation of structure with reactivity – solvent effects – rearrangements involving carbocations – Wagner-Meerwein and dienone-phenol rearrangements. Aromatic nucleophilic substitutions – SN1, SNAr, Benzyne mechanism – reactivity orientation – Ullmann, Sandmeyer and Chichibabin reaction – rearrangements involving nucleophilic substitution – Stevens – Sommelet Hauser and von-Richter rearrangements. NUCLEOPHILIC SUBSTITUTION Mechanism of Aliphatic Nucleophilic Substitution. Aliphatic nucleophilic substitution clearly involves the donation of a lone pair from the nucleophile to the tetrahedral, electrophilic carbon bonded to a halogen. For that reason, it attracts to nucleophile In organic chemistry and inorganic chemistry, nucleophilic substitution is a fundamental class of reactions in which a leaving group(nucleophile) is replaced by an electron rich compound(nucleophile). The whole molecular entity of which the electrophile and the leaving group are part is usually called the substrate. The nucleophile essentially attempts to replace the leaving group as the primary substituent in the reaction itself, as a part of another molecule. The most general form of the reaction may be given as the following: Nuc: + R-LG → R-Nuc + LG: The electron pair (:) from the nucleophile(Nuc) attacks the substrate (R-LG) forming a new 1 bond, while the leaving group (LG) departs with an electron pair. The principal product in this case is R-Nuc. The nucleophile may be electrically neutral or negatively charged, whereas the substrate is typically neutral or positively charged.