Kinetics 651

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SF Chemical Kinetics. Microscopic Theories of Chemical Reaction Kinetics

SF Chemical Kinetics. Lecture 5. Microscopic theory of chemical reaction kinetics. Microscopic theories of chemical reaction kinetics. • A basic aim is to calculate the rate constant for a chemical reaction from first principles using fundamental physics. • Any microscopic level theory of chemical reaction kinetics must result in the derivation of an expression for the rate constant that is consistent with the empirical Arrhenius equation. • A microscopic model should furthermore provide a reasonable interpretation of the pre-exponential factor A and the activation energy EA in the Arrhenius equation. • We will examine two microscopic models for chemical reactions : – The collision theory. – The activated complex theory. • The main emphasis will be on gas phase bimolecular reactions since reactions in the gas phase are the most simple reaction types. 1 References for Microscopic Theory of Reaction Rates. • Effect of temperature on reaction rate. – Burrows et al Chemistry3, Section 8. 7, pp. 383-389. • Collision Theory/ Activated Complex Theory. – Burrows et al Chemistry3, Section 8.8, pp.390-395. – Atkins, de Paula, Physical Chemistry 9th edition, Chapter 22, Reaction Dynamics. Section. 22.1, pp.832-838. – Atkins, de Paula, Physical Chemistry 9th edition, Chapter 22, Section.22.4-22.5, pp. 843-850. Collision theory of bimolecular gas phase reactions. • We focus attention on gas phase reactions and assume that chemical reactivity is due to collisions between molecules. • The theoretical approach is based on the kinetic theory of gases. • Molecules are assumed to be hard structureless spheres. Hence the model neglects the discrete chemical structure of an individual molecule. This assumption is unrealistic. • We also assume that no interaction between molecules until contact. -

Department of Chemistry

07 Sept 2020 2020–2021 Module Outlines MSc Chemistry MSc Chemistry with Medicinal Chemistry Please note: This handbook contains outlines for the modules comprise the lecture courses for all the MSc Chemistry and Chemistry with Medicinal Chemistry courses. The outline is also posted on Moodle for each lecture module. If there are any updates to these published outlines, this will be posted on the Level 4 Moodle, showing the date, to indicate that there has been an update. PGT CLASS HEAD: Dr Stephen Sproules, Room A5-14 Phone (direct):0141-330-3719 email: [email protected] LEVEL 4 CLASS HEAD: Dr Linnea Soler, Room A4-36 Phone (direct):0141-330-5345 email: [email protected] COURSE SECRETARY: Mrs Susan Lumgair, Room A4-30 (Teaching Office) Phone: 0141-330-3243 email: [email protected] TEACHING ADMINISTRATOR: Ms Angela Woolton, Room A4-27 (near Teaching Office) Phone: 0141-330-7704 email: [email protected] Module Topics for Lecture Courses The Course Information Table below shows, for each of the courses (e.g. Organic, Inorganic, etc), the lecture modules and associated lecturer. Chemistry with Medicinal Chemistry students take modules marked # in place of modules marked ¶. Organic Organic Course Modules Lecturer Chem (o) o1 Pericyclic Reactions Dr Sutherland o2 Heterocyclic Systems Dr Boyer o3 Advanced Organic Synthesis Dr Prunet o4 Polymer Chemistry Dr Schmidt o5m Asymmetric Synthesis Prof Clark o6m Organic Materials Dr Draper Inorganic Inorganic Course Modules Lecturer Chem (i) i1 Metals in Medicine -

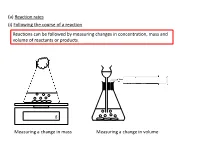

(A) Reaction Rates (I) Following the Course of a Reaction Reactions Can Be Followed by Measuring Changes in Concentration, Mass and Volume of Reactants Or Products

(a) Reaction rates (i) Following the course of a reaction Reactions can be followed by measuring changes in concentration, mass and volume of reactants or products. g Measuring a change in mass Measuring a change in volume Volume of gas produced of gas Volume Mass of beaker and contents of beaker Mass Time Time The rate is highest at the start of the reaction because the concentration of reactants is highest at this point. The steepness (gradient) of the plotted line indicates the rate of the reaction. We can also measure changes in product concentration using a pH meter for reactions involving acids or alkalis, or by taking small samples and analysing them by titration or spectrophotometry. Concentration reactant Time Calculating the average rate The average rate of a reaction, or stage in a reaction, can be calculated from initial and final quantities and the time interval. change in measured factor Average rate = change in time Units of rate The unit of rate is simply the unit in which the quantity of substance is measured divided by the unit of time used. Using the accepted notation, ‘divided by’ is represented by unit-1. For example, a change in volume measured in cm3 over a time measured in minutes would give a rate with the units cm3min-1. 0.05-0.00 Rate = 50-0 1 - 0.05 = 50 = 0.001moll-1s-1 Concentration moll Concentration 0.075-0.05 Rate = 100-50 0.025 = 50 = 0.0005moll-1s-1 The rate of a reaction, or stage in a reaction, is proportional to the reciprocal of the time taken. -

Predictive Models for Kinetic Parameters of Cycloaddition

Predictive Models for Kinetic Parameters of Cycloaddition Reactions Marta Glavatskikh, Timur Madzhidov, Dragos Horvath, Ramil Nugmanov, Timur Gimadiev, Daria Malakhova, Gilles Marcou, Alexandre Varnek To cite this version: Marta Glavatskikh, Timur Madzhidov, Dragos Horvath, Ramil Nugmanov, Timur Gimadiev, et al.. Predictive Models for Kinetic Parameters of Cycloaddition Reactions. Molecular Informatics, Wiley- VCH, 2018, 38 (1-2), pp.1800077. 10.1002/minf.201800077. hal-02346844 HAL Id: hal-02346844 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02346844 Submitted on 5 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 0DQXVFULSW &OLFNKHUHWRGRZQORDG0DQXVFULSW&$UHYLVLRQGRF[ Predictive models for kinetic parameters of cycloaddition reactions Marta Glavatskikh[a,b], Timur Madzhidov[b], Dragos Horvath[a], Ramil Nugmanov[b], Timur Gimadiev[a,b], Daria Malakhova[b], Gilles Marcou[a] and Alexandre Varnek*[a] [a] Laboratoire de Chémoinformatique, UMR 7140 CNRS, Université de Strasbourg, 1, rue Blaise Pascal, 67000 Strasbourg, France; [b] Laboratory of Chemoinformatics and Molecular Modeling, Butlerov Institute of Chemistry, Kazan Federal University, Kremlyovskaya str. 18, Kazan, Russia Abstract This paper reports SVR (Support Vector Regression) and GTM (Generative Topographic Mapping) modeling of three kinetic properties of cycloaddition reactions: rate constant (logk), activation energy (Ea) and pre-exponential factor (logA). -

CHEMICAL KINETICS Pt 2 Reaction Mechanisms Reaction Mechanism

Reaction Mechanism (continued) CHEMICAL The reaction KINETICS 2 C H O +→5O + 6CO 4H O Pt 2 3 4 3 2 2 2 • has many steps in the reaction mechanism. Objectives ! Be able to describe the collision and Reaction Mechanisms transition-state theories • Even though a balanced chemical equation ! Be able to use the Arrhenius theory to may give the ultimate result of a reaction, determine the activation energy for a reaction and to predict rate constants what actually happens in the reaction may take place in several steps. ! Be able to relate the molecularity of the reaction and the reaction rate and • This “pathway” the reaction takes is referred to describle the concept of the “rate- as the reaction mechanism. determining” step • The individual steps in the larger overall reaction are referred to as elementary ! Be able to describe the role of a catalyst and homogeneous, heterogeneous and reactions. enzyme catalysis Reaction Mechanisms Often Used Terms •Intermediate: formed in one step and used up in a subsequent step and so is never seen as a product. The series of steps by which a chemical reaction occurs. •Molecularity: the number of species that must collide to produce the reaction indicated by that A chemical equation does not tell us how step. reactants become products - it is a summary of the overall process. •Elementary Step: A reaction whose rate law can be written from its molecularity. •uni, bi and termolecular 1 Elementary Reactions Elementary Reactions • Consider the reaction of nitrogen dioxide with • Each step is a singular molecular event carbon monoxide. -

CHEMISTRY.Pdf

SYLLABUS FOR THE POST OF LECTURER 10+2 CHEMISTRY PHYSICAL CHEMISTRY Thermodynamics Partial molar properties; partial molar free energy, partial molar volume from density measurements, Gibbs- Duhem equation, Fugacity of gases, calculation of fugacity from P, T data concept of ideal solutions, Rault’s Law, Duhen-Margules equation, Henry Law, Concept of activity and activity co-efficients. Chemical Kinetics and Photochemistry Theories of reaction rates, absolute reaction rates and collision theory, ionic reactions, photochemical reactions, explosion reactions, flash photolysis. Surface Chemistry Langmuir adsorption isotherm, B.E.T. adsorption isotherm, Chemisorptions-its kinetics and thermodynamics. Electro Chemistry Liquid junction potential Quantum Chemistry Eigen functions and eigen values; Angular momentum and eigen values of angular momentum, spin, Pauli exclusion principle, operator concept and wave mechanics of simple systems, particle in ring and rigid rotator, simple harmonic oscillator and the Hydrogen atom. Postulates of quantum, mechanics, elementary concept of perturbation theory, application of variation method and perturbation method to simple harmonic oscillator. Schrödinger’s equation (time dependent). INORGANIC CHEMISTRY Description of VB, MO and VSEPR theories, Three electron bond, Hydrogen bond, theories of hydrogen bonding, Inorganic semi conductors and super conductors, structure and bonding in Zoolites and orthosilicates, Borates; Nitrogen-Phosphorus cyclic compounds polyhalides. Organometallic Compounds Definition, classification, Transition metal-to carbon sigma bonded compounds. Synthesis and bonding of Alkyne and allyl transition metal complexes, cyclo pentadienyl and arene metal complexes, Homogeneous catalysis involving organometallic compounds; Hydrogenation, Polymerisation, preparation, structure and applications of organometallic compounds of Boron. Coordination Numbers Spectrochemical series, John-Teller distortion, colour and magnetic properties of coordination compounds, crystal field theory, M.O treatment of actahedral complexes. -

Chemistry (CHEM) 1

Chemistry (CHEM) 1 CHEMISTRY (CHEM) GenEd Learning Objective: Key Literacies CHEM 5: Kitchen Chemistry CHEM 1: Molecular Science 3 Credits 3 Credits CHEM 5 Kitchen Chemistry (3) (GN)(BA) CHEM 5 focuses on an Selected concepts and topics designed to give non-science majors an elementary discussion of the chemistry associated with foods and appreciation for how chemistry impacts everyday life. Students who cooking. It incorporates lectures and videos, reading, problem-solving, have received credit for CHEM 3, 101, 130, or 110 may not schedule and "edible"; home experiments to facilitate students' understanding of this course. CHEM 1 is designed for students who want to gain a better chemical concepts and scientific inquiry within the context of food and appreciation of chemistry and how it applies to everyone's everyday cooking. Please note that this is a chemistry class presented in a real life. You are expected to have an interest in understanding the nature of world interactive way, not a cooking class! The course will start from a science, but not necessarily to have any formal training in the sciences. primer on food groups and cooking, proceed to the structures of foods, During the course, you will explore important societal issues that can be and end with studies of the physical and chemical changes observed in better understood knowing some concepts in chemistry. The course is foods. Students will develop an enhanced understanding of the chemical largely descriptive, though occasionally a few simple calculations will principles involved in food products and common cooking techniques. be done to illuminate specific information. -

On Rate Constants: Simple Collision Theory, Arrhenius Behavior, and Activated Complex Theory

On Rate Constants: Simple Collision Theory, Arrhenius Behavior, and Activated Complex Theory 17th February 2010 0.1 Introduction Up to now, we haven't said much regarding the rate constant k. It should be apparent from the discussions, however, that: • k is constant at a specific temperature, T and pressure, P • thus, k = k(T,P) (rate constant is temperature and pressure depen- dent) • bear in mind that the rate constant is independent of concentrations, as the reaction rate, or velocity itself is treated explicity to be concen- tration dependent In the following, we will consider how the physical, microscopic detaails of reactions can be reasoned to be embodied in the rate constant, k. 1 Simple Collision Theory Let's consider the following gas-phase elementary reaction: A + B ! Products The reaction rate is straightforwardly: 1 Rate = k[A]α[B]β = k[A]1[B]1 α = 1 β = 1 N N = k A B V = volume V V Recall previous discussions of the total collisional frequency for heteroge- neous reactions: 8kT ∗ ∗ ZAB = σAB nA nB s πµ ∗ NA ∗ NB where the nA = V ; nB = V are number of molecules/particles per unit volume. We can see the following: 8kT NA NB ZAB = σAB s πµ V V k Here we see that the concepts| of collisions{z } from simple kinetic theory can be fundamentally related to ideas of reactions, particularly when we consider that elementary reactions (only for which we can write rate expressions based on molecularity and order mapping) can be thought of proceeding due to collisions (or interactions of some sort) of monomers (unimolecular), dimers(bimolecular), trimers (trimolecular), etc. -

Module 7 : Theories of Reaction Rates Lecture 32 : Theories of Reaction Rates - I : Collision Theory Objectives

Module 7 : Theories of Reaction Rates Lecture 32 : Theories Of Reaction Rates - I : Collision Theory Objectives After studying this lecture you will be able to do the following. Calculate collision frequency using kinetic theory. Distinguish between collision cross section and reaction cross section. Compare collision theory with Arrhenius theory and experiments. Define the steric factor. Rationalize the departure of collision theory from experiments for ionic reactions using the harpoon mechanism. 32.1Introduction In the earlier lectures on chemical kinetics, we have studied the empirical aspects in detail. We now begin the theoretical explanations of chemical rate processes. This is one of the most challenging areas in chemistry. Molecular structure is fairly well understood through the advances in spectroscopy and quantum chemistry. With the knowledge of the same molecular structures and intermolecular forces, chemical equilibrium (thermodynamics) can be predicted quite accurately. An understanding the rates of processes microscopically requires answers to several interesting questions. Some of the main questions are as follows. How close should the molecules approach one another for the reaction to occur? Does the reaction "occur" only after reaching this separation or does it start well before the distance of closest separation is reached? Do all the reactants react identically or is there a distribution over several possibilities? Do all "encounters" between the reactants produce the products? How closely can we monitor the progress of the reaction theoretically (as well as experimentally)? Over the last four decades, the time resolution of this monitoring has improved dramatically from microseconds to femtoseconds. While most of the above questions relate to gas phase processes, solution reactions have the additional contributions from the participation of the solvent. -

Che 505 Chapter 6N

ChE 505 – Chapter 6N Updated 01/31/05 6. THEORY OF ELEMENTARY REACTIONS 6.1 Collision Theory Collision theory is the extension of the kinetic theory of gases in predicting reaction rates of a bimolecular gas phase reaction of the type: A + A → P (1) A + B → P (2) It is assumed that the reaction rate expressed in terms of disappearance of molecules of A is given by: ⎛ molecules⎞ − r? ⎜ ⎟ =2 fZ for reaction(1) A ⎝ cm 3 s ⎠ AA A factor two appears on the right hand side of eq (1) because for each collision two molecules of A disappear. ⎛ molecules⎞ − r? =−r? ⎜ ⎟ = fZ for reaction (2) A B ⎝ cm 3 s ⎠ AB where 3 ZA B - is the total number of collisions between molecules A and B in 1 cm of reaction mixture per second (frequency of collision per 1 cm3) 3 Z A A - is the total number of collisions among the molecules A in 1 cm per second f - the fraction of molecules that possess the required excess energy for reaction i.e the fraction of molecules that upon collision will react. The kinetic theory of gases postulates that the collision frequency Z A B is proportional to the size of the "target", to the relative mean velocity u AB,, and to the number concentrations of both molecular species. The size of the "target" is interpreted as the maximum area perpendicular to the trajectory of the moving A (or B ) molecule which when it contains a B (or A ) molecule will lead to an inevitable collision of the two. -

The Rate of a Chemical Reaction

Science Enhanced Scope and Sequence – Chemistry The Rate of a Chemical Reaction Strand Nomenclature, Chemical Formulas, and Reactions Topic Investigating chemical reactions and equations Primary SOL CH.3 The student will investigate and understand how conservation of energy and matter is expressed in chemical formulas and balanced equations. Key concepts include f) reaction rates, kinetics, and equilibrium. Related SOL CH.1 The student will investigate and understand that experiments in which variables are measured, analyzed, and evaluated produce observations and verifiable data. Key concepts include a) designated laboratory techniques; b) safe use of chemicals and equipment; c) proper response to emergency situations. Background Information Chemical kinetics is the study of rates of chemical reactions and reaction mechanisms—when and how fast a chemical reaction occurs. Many factors influence reaction rate. Two of the most important are the nature and properties of the reactants themselves, including particle size (surface area). Other factors, such as concentration, temperature, pressure, or the presence of a catalyst, will also affect the rate of a reaction. Collision theory can explain how these factors affect reaction rate. Collision-theory concepts: For a chemical change to occur, old bonds must be broken (an endothermic process) and new bonds must be formed (an exothermic process). The reactants must collide with each other to form products. The reactants must collide with each other at the correct angle and the correct molecular orientation. The collisions between reactants must be effective—i.e., they must have enough energy (called “activation energy”). Activation energy is the minimum energy needed for a reaction to occur. -

A Particle-Based Dissolution Model Using Chemical Collision Energy

A particle-based dissolution model using chemical collision energy Min Jiang1, Richard Southern1 and Jian Jun Zhang1 1National Centre for Computer Animation, Bournemouth University, Bournemouth, UK fmjiang, rsouthern, [email protected] Keywords: Dissolution, Solute, Solvent, Collision Theory, Activation Energy, Particle Excitation, SPH, Erosion. Abstract: We propose a new energy-based method for real-time dissolution simulation. A unified particle representation is used for both fluid solvent and solid solute. We derive a novel dissolution model from the collision theory in chemical reactions: physical laws govern the local excitation of solid particles based on the relative motion of the fluid and solid. When the local excitation energy exceeds a user specified threshold (activation energy), the particle will be dislodged from the solid. Unlike previous methods, our model ensures that the dissolution result is independent of solute sampling resolution. We also establish a mathematical relationship between the activation energy, the inter-facial surface area, and the total dissolution time — allowing for accurate artistic control over the global dissolution rate while maintaining the physical plausibility of the simulation. We demonstrate applications of our method using a number of practical examples, including antacid pills dissolving in water and hydraulic erosion of non-homogeneous terrains. Our method is straightforward to incorporate with existing particle-based fluid simulations. 1 INTRODUCTION low resolution sampling of the solute. A solute particle will become dislodged if the lo- cal energy exceeds a user specified activation energy. The reliance of films and games on realistic fluid While physically justified, this threshold does not pro- simulations has led to the popularity of this research vide a user with an intuition of the total dissolution topic, with most work in this field focused on the time.