Information in Advance of the Adoption of the List of Issues on Brazil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rights in the Pandemic Mapping the Impact of Covid-19 on Human Rights

Bulletin No. 10 RIGHTS IN THE PANDEMIC MAPPING THE IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON HUMAN RIGHTS SÃO PAULO • 20/01/2021 OFFPRINT Cite: Ventura, D.; Reis, R. An unprecedented attack on human rights in Brazil: the timeline of the federal government’s strategy to spread Covid-19. Offprint. Translation by Luis Misiara, revision by Jameson Martins. Bulletin Rights in the Pandemic n. 10, São Paulo, Brazil, CEPEDISA/USP and Conectas Human Rights, January 2021. Credits: The Bulletin entitled RIGHTS IN THE PANDEMIC - Mapping the impact of Covid-19 on human rights is a scientific publication of Conectas Human Rights and the Center for Studies and Research on Health Law (CEPEDISA) of the University of São Paulo (USP) that will be released every two weeks for a limited time. Editors: Camila Lissa Asano, Deisy de Freitas Lima Ventura, Fernando Mussa Abujamra Aith, Rossana Rocha Reis and Tatiane Bomfim Ribeiro Researchers: André Bastos Ferreira, Alexia Viana da Rosa, Alexsander Silva Farias, Giovanna Dutra Silva Valentim and Lucas Bertola Herzog AN UNPRECEDENTED ATTACK ON HUMAN RIGHTS IN BRAZIL: the timeline of the federal government’s strategy to spread Covid-19 n February 2020, the Ministry of Health 1. federal normative acts, including the I presented the Contingency Plan for the enacting of rules by federal authorities and response to Covid-191. Unlike other countries2, bodies and presidential vetoes; the document did not contain any reference to ethics, human rights or fundamental freedoms, 2. acts of obstruction to state and municipal not even to those related to the emergency government efforts to respond to the routine, such as the management of scarce pandemic; and supplies or the doctor-patient relationship, ignoring both Brazilian law (Law no. -

Golden Lion Tamarin Conservation

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 CONTENTS 46 DONATIONS 72 LEGAL 85 SPECIAL UNIT OBLIGATIONS PROJECTS UNIT UNIT 3 Letter from the CEO 47 COPAÍBAS 62 GEF TERRESTRE 73 FRANCISCANA 86 SUZANO 4 Perspectives Community, Protected Areas Strategies for the CONSERVATION Emergency Call Support 5 FUNBIO 25 years and Indigenous Peoples Project Conservation, Restoration and Conservation in Franciscana 87 PROJETO K 6 Mission, Vision and Values in the Brazilian Amazon and Management of Biodiversity Management Area I Knowledge for Action 7 SDG and Contributions Cerrado Savannah in the Caatinga, Pampa and 76 ENVIRONMENTAL 10 Timeline 50 ARPA Pantanal EDUCATION 16 FUNBIO Amazon Region Protected 64 ATLANTIC FOREST Implementing Environmental GEF AGENCY 16 How We Work Areas Program Biodiversity and Climate Education and Income- 88 17 In Numbers 53 REM MT Change in the Atlantic Forest generation Projects for FUNBIO 20 List of Funding Sources 2020 REDD Early Movers (REM) 65 PROBIO II Improved Environmental 21 Organizational Flow Chart Global Program – Mato Grosso Opportunities Fund of the Quality at Fishing 89 PRO-SPECIES 22 Governance 56 TRADITION AND FUTURE National Public/Private Communities in the State National Strategic Project 23 Transparency IN THE AMAZON Integrated Actions for of Rio de Janeiro for the Conservation of 24 Ethics Committee 57 KAYAPÓ FUND Biodiversity Project 78 MARINE AND FISHERIES Endangered Species 25 Policies and Safeguards 59 A MILLION TREES FOR 67 AMAPÁ FUND RESEARCH 26 National Agencies FUNBIO THE XINGU 68 ABROLHOS LAND Support for Marine and -

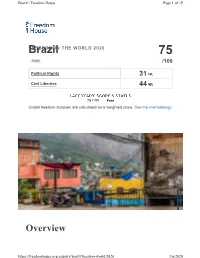

Freedom in the World Report 2020

Brazil | Freedom House Page 1 of 19 BrazilFREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 75 FREE /100 Political Rights 31 Civil Liberties 44 75 Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. Overview https://freedomhouse.org/country/brazil/freedom-world/2020 3/6/2020 Brazil | Freedom House Page 2 of 19 Brazil is a democracy that holds competitive elections, and the political arena is characterized by vibrant public debate. However, independent journalists and civil society activists risk harassment and violent attack, and the government has struggled to address high rates of violent crime and disproportionate violence against and economic exclusion of minorities. Corruption is endemic at top levels, contributing to widespread disillusionment with traditional political parties. Societal discrimination and violence against LGBT+ people remains a serious problem. Key Developments in 2019 • In June, revelations emerged that Justice Minister Sérgio Moro, when he had served as a judge, colluded with federal prosecutors by offered advice on how to handle the corruption case against former president Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, who was convicted of those charges in 2017. The Supreme Court later ruled that defendants could only be imprisoned after all appeals to higher courts had been exhausted, paving the way for Lula’s release from detention in November. • The legislature’s approval of a major pension reform in the fall marked a victory for Brazil’s far-right president, Jair Bolsonaro, who was inaugurated in January after winning the 2018 election. It also signaled a return to the business of governing, following a period in which the executive and legislative branches were preoccupied with major corruption scandals and an impeachment process. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO Race and Political

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO Race and Political Representation in Brazil A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Andrew Janusz Committee in charge: Professor Scott Desposato, Co-Chair Professor Zoltan Hajnal, Co-Chair Professor Gary Jacobson Professor Simeon Nichter Professor Carlos Waisman 2019 Copyright Andrew Janusz, 2019 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Andrew Janusz is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Co-Chair University of California San Diego 2019 iii DEDICATION For my mother, Betty. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page . iii Dedication . iv Table of Contents . v List of Figures . vi List of Tables . vii Acknowledgements . viii Vita ............................................... x Abstract of the Dissertation . xi Introduction . 1 Chapter 1 The Political Importance of Race . 10 Chapter 2 Racial Positioning in Brazilian Elections . 20 Appendix A . 49 Chapter 3 Ascribed Race and Electoral Success . 51 Appendix A . 84 Chapter 4 Race and Substantive Representation . 87 Appendix A . 118 Appendix B . 120 Chapter 5 Conclusion . 122 Bibliography . 123 v LIST OF FIGURES Figure 2.1: Inconsistency in Candidate Responses Across Elections . 27 Figure 2.2: Politicians Relinquish Membership in Small Racial Groups . 31 Figure 2.3: Politicians Switch Into Large Racial Groups . 32 Figure 2.4: Mayors Retain Membership in the Largest Racial Group . 34 Figure 2.5: Mayors Switch Into the Largest Racial Group . 35 Figure 2.6: Racial Ambiguity and Racial Switching . 37 Figure 2.7: Politicians Remain in Large Groups . 43 Figure 2.8: Politicians Switch Into Large Groups . -

“Pacification” for Whom?

“PACIFICATION” FOR WHOM? Marielle Franco MARIELLE PRESENT! Marielle Franco, aged 38, a Rio de Janeiro city councilor elected with 46,502 votes in 2016, was shot dead in an ambush on 14 March 2018. As a black woman, a lesbian and a mother who grew up in the Maré favela, Marielle turned to human rights activism when she was 19 years old and routinely had to contend with machismo, racism and LGBTphobia in her work. Nothing changed when she served as city councilor: shortly after taking office, Marielle was made chair of the Rio de Janeiro City Council Women’s Commission – a job whose results were released three months after her murder.1 Five of the bills she submitted were approved: Bill 17/2017 – Espaço Coruja (“Night Owl”): crèches for parents who work or study at night; Bill 103/2017 – Dia de Thereza de Benguela no Dia da Mulher Negra: a homage to the 18th century black leader Thereza de Benguela to be celebrated on the same date as Black Woman’s Day; Bill 417/2017 – Assédio não é passageiro: a campaign to raise awareness and combat sexual assault and harassment; Bill 515/2017 – Efetivação das Medidas Socioeducativas em Meio Aberto: to guarantee social and educational measures for young offenders; Bill 555/2017 – Dossiê Mulher Carioca: compilation of an annual report with statistics on violence against women. As a long-time vocal opponent of the militarisation of life, her political and academic output demonstrate the strength of someone who knew, from an early age, the devastation caused by institutional violence. -

Apresentação Do Powerpoint

ESTRUTURA MINISTERIAL DO GOVERNO BOLSONARO PRESIDENTE DA REPÚBLICA Jair Bolsonaro VICE-PRESIDENTE DA REPÚBLICA Hamilton Mourão CIÊNCIA, TECNOLOGIA, DESENVOLVIMENTO SECRETARIA DE GABINETE DE AGRICULTURA, CIDADANIA DEFESA ECONOMIA CASA CIVIL ADVOGADO-GERAL INOVAÇÕES E REGIONAL SECRETARIA-GERAL SEGURANÇA PECUÁRIA E Onyx Lorenzoni Fernando Paulo GOVERNO DA UNIÃO COMUNICAÇÃO Rogério Marinho Walter Sousa INSTITUCIONAL ABASTECIMENTO Azevedo Guedes Luiz Eduardo Ramos Floriano Peixoto André Luiz Mendonça Marcos Pontes Braga Neto Augusto Heleno Tereza Cristina TURISMO BANCO MINAS E MULHER, DA CONTROLADORIA-GERAL EDUCAÇÃO INFRAESTRUTURA JUSTIÇA E MEIO RELAÇÕES SAÚDE Marcelo CENTRAL ENERGIA FAMÍLIA E DA UNIÃO Abraham Tarcísio Gomes de SEGURANÇA AMBIENTE EXTERIORES Luiz Henrique Álvaro Roberto Campos Bento Costa DOS DIREITOS Wagner Rosário Weintraub Freitas PÚBLICA Ricardo Salles Ernesto Araújo Mandetta Antônio Neto Sérgio Moro Lima Leite HUMANOS Damares Alves CASA CIVIL DA PRESIDÊNCIA DA REPÚBLICA Ministro - Walter Souza Braga Netto Entidade Órgãos de assistência direta e imediata ao ministro de Estado Órgãos específicos singulares vinculada Fonte: Decretos nº 9.679; nº 9.698; e nº 9.979, de Subchefia de 2019 Análise e Diretoria de Assessoria Diretoria de Acompanha Subchefia de Secretaria Gabinete do Governança, Especial de Secretaria ITI – Instituto Assessoria Secretário- Gestão e mento de Articulação e Secretaria Especial do Ministro - Inovação e Comunicaçã Especial de Nacional de Especial - Executivo - Informação - Políticas Monitoramen Especial -

Federative Republic of Brazil • National Press

ISSN 1677-7042 FEDERATIVE REPUBLIC OF BRAZIL • NATIONAL PRESS Year CLVIII Nº 144-A Brasília - DF, Wednesday, July 29, 2020 1 § 4 In the event of entry into the country by road, other land or summary by water transport, the exceptions referred to in item II and paragraphs "a" and "c" of item V of caput they do not apply to foreigners from the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela. Presidency of the Republic ............................................... .................................................. ......... 1 ..................... This complete edition of the DOU consists of 1 page .................... Art. 4 The restrictions mentioned in this Ordinance do not prevent: I - the execution of previously authorized cross-border humanitarian actions Presidency of the Republic by local health authorities; II - the traffic of border residents in twin cities, through the CIVIL HOUSE presentation of a border resident document or other supporting document, provided that reciprocity in the treatment of Brazilians by the neighboring country is guaranteed; and Ordinance CC-PR / MJSP / MINFRA / MS No. 1, OF JULY 29, 2020 III - the free traffic of road cargo transportation, even if the driver is not It provides for the exceptional and temporary restriction on the entry of fit in the list referred to in art. 3rd, in the manner provided for in the legislation. foreigners into the country, of any nationality, as recommended by the National Health Surveillance Agency - Anvisa. Single paragraph. The provisions of item II of caput does not apply to the border with Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela. THE CHIEF MINISTERS OF THE CIVIL HOUSE OF THE PRESIDENCY OF THE REPUBLIC, Art. 5 Exceptionally, the foreigner who is in a land border country and JUSTICE AND PUBLIC SAFETY, INFRASTRUCTURE AND HEALTH, in the use of the powers conferred on them by having to cross it to board a flight back to your country of residence may enter the Federative Republic of Brazil with art. -

Ordinance No. 518, of NOVEMBER 12, 2020 - DOU - National Press

11/18/2020 Ordinance No. 518, OF NOVEMBER 12, 2020 - DOU - National Press OFFICIAL DIARY OF THE UNION Posted in: 12/11/2020 | Edition: 216-A | Section: 1 - Extra A | Page: 1 Órgão: Presidência da República/Casa Civil Ordinance No. 518, OF NOVEMBER 12, 2020 It provides for the exceptional and temporary restriction on the entry of foreigners into the country, of any nationality, as recommended by the National Health Surveillance Agency - Anvisa. THE CHIEF MINISTERS OF THE CIVIL HOUSE OF THE PRESIDENCY OF THE REPUBLIC, JUSTICE AND PUBLIC SECURITY, INFRASTRUCTURE AND HEALTH, in the use of the powers conferred on them by art. 87, sole paragraph, items I and II, of the Constitution, and art. 3rd, art. 35, art. 37 and art. 47 of Law No. 13,844, of June 18, 2019, and in view of the provisions of art. 3rd, caput, item VI, of Law No. 13,979, of February 6, 2020, and Considering the declaration of public health emergency of international importance by the World Health Organization on January 30, 2020, due to the human infection with the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (covid-19); Considering that it is a principle of the National Public Security and Social Defense Policy, provided for in item VI of the caput of art. 4 of Law No. 13,675, of June 11, 2018, the efficiency in preventing and reducing risks in emergency situations that may affect people's lives; Considering the need to give effectiveness to the health measures to respond to the covid-19 pandemic provided for in Ordinance No. -

The Murder of Brazilian Councilwoman and Activist Marielle Franco

Analyzing polarization in Twitter: The murder of Brazilian councilwoman and activist Marielle Franco Abstract. Social media has allowed people to publicly express, at near zero cost, their opinions and emotions on a wide range of topics. This recent scenario allows the analysis of social media platforms to several purposes, such as predicting elections, exploiting influential users or understanding the polarization of public opinion on polemic topics. In this work, we analyze the Brazilian public percep- tion related to the murder of a Rio councilwoman, Marielle Franco, member of a left-wing party and human-rights activist. We propose a polarity score to capture whether the tweet is positive or negative and then we analyze the score evolution over the time, after the murder. Finally, we evaluate our approach correlating the polarity score with human judgment over a randomly sampled set of tweets. Our preliminary results show how to measure polarity on public opinion using a weighted dictionary and how it changes over time. Keywords: Social media, Sentiment analysis, Opinion Mining. 1 Introduction Over the last years, an increasing number of people actively use the Internet to exchange information and convey emotions, allowing studies that examine how technology can influence people’s feelings. Social media platforms have become an important source of data to capture those emotions, opinions and sentiments on several topics and debates – from the Mediterranean refugee’s crisis (Coletto et al., 2016) to political leanings (Conover et al., 2011) (Tumasjan et al., 2010). Twitter platform is especially powerful because of its very nature, which encourages people to have public conversations and debates, sharing their thoughts with others, creating solidary networks or politically engaged movements. -

Narrative Disputes Over Family-Farming Public Policies in Brazil: Conservative Attacks and Restricted Countermovements

Niederle, Paulo, et al. 2019. Narrative Disputes over Family-Farming Public Policies in Brazil: Conservative Attacks and Restricted Countermovements. Latin American Research Review 54(3), pp. 707–720. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.366 SOCIOLOGY Narrative Disputes over Family-Farming Public Policies in Brazil: Conservative Attacks and Restricted Countermovements Paulo Niederle1, Catia Grisa1, Everton Lazaretti Picolotto2 and Denis Soldera1 1 Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, BR 2 Federal University of Santa Maria, BR Corresponding author: Paulo Niederle ([email protected]) This article analyzes the conservative narratives underlying current changes in Brazilian rural development public policies. It first presents an overview of the recognition and institutionalization of family farming and the main policies created in support of this segment. Subsequently, it discusses how a conservative narrative started to question the ability of these policies to integrate family farmers into modern agricultural markets. Focusing on how this narrative tries to legitimate a new “referential” for public action, the article analyzes the discourse on newly occurring segregation between agricultural policies for productive farmers and social policies for unproductive ones. It demonstrates how this discourse excludes family farmers from the social pact that prevailed over the past three decades and depended on the state as an actor to mediate the contradictions in the unstable coexistence of agribusiness and family-farming logics. Finally, it analyzes how rural social movements are reacting to this process. Este artigo analisa as narrativas conservadoras que sustentam as atuais mudanças nas políticas públicas de desenvolvimento rural no Brasil. Em primeiro lugar, analisa o processo de reconhecimento e institucionalização da agricultura familiar e das principais políticas criadas para este segmento. -

Ata Da 3 ª Reunião, Ordinária, Da Comissão De Relações Exteriores E

SENADO FEDERAL Secretaria-Geral da Mesa ATA DA 3ª REUNIÃO, ORDINÁRIA, DA COMISSÃO DE RELAÇÕES EXTERIORES E DEFESA NACIONAL DA 3ª SESSÃO LEGISLATIVA ORDINÁRIA DA 56ª LEGISLATURA, REALIZADA EM 29 DE ABRIL DE 2021, QUINTA-FEIRA, NO SENADO FEDERAL, PLENÁRIO VIRTUAL DO SENADO FEDERAL. Às dez horas e quatro minutos do dia vinte e nove de abril de dois mil e vinte e um, no Plenário Virtual do Senado Federal, sob a Presidência da Senadora Kátia Abreu, reúne-se a Comissão de Relações Exteriores e Defesa Nacional com a presença dos Senadores Nilda Gondim, Esperidião Amin, Mara Gabrilli, Roberto Rocha, Flávio Arns, Marcos do Val, Soraya Thronicke, Nelsinho Trad, Carlos Viana, Chico Rodrigues, Telmário Mota, Cid Gomes e Fabiano Contarato, e ainda dos Senadores não membros Luis Carlos Heinze e Carlos Fávaro. Deixam de comparecer os Senadores Renan Calheiros, Fernando Bezerra Coelho, Jarbas Vasconcelos, Antonio Anastasia, Zequinha Marinho, Jaques Wagner, Humberto Costa e Randolfe Rodrigues. Havendo número regimental, a reunião é aberta. Passa-se à apreciação da pauta: Audiência Pública Interativa. Finalidade: Ouvir na qualidade de convidado o Excelentíssimo Senhor General Walter Souza Braga Netto - Ministro da Defesa, para prestar informações no âmbito de suas competências, conforme disposto art 103, § 2ºdo RISF. Participantes: General Walter Souza Braga Netto, Ministro da Defesa; Almirante Almir Garnier Santos, Comandante da Marinha.; General Paulo Sérgio Nogueira, Comandante do Exercito.; e Tenente-Brigadeiro do Ar Carlos de Almeida Baptista Junior, Comandante da Aeronáutica.. Resultado: Audiência Pública Interativa realizada. Nada mais havendo a tratar, encerra-se a reunião às quatorze horas e cinco minutos. Após aprovação, a presente Ata será assinada pela Senhora Presidente e publicada no Diário do Senado Federal, juntamente com a íntegra das notas taquigráficas. -

Universidade Da Beira Interior, Portugal)

DIRECTOR João Carlos Correia (Universidade da Beira Interior, Portugal) EDITORES | EDITORS João Carlos Correia (Universidade da Beira Interior, Portugal) Anabela Gradim (Universidade da Beira Interior, Portugal) PAINEL CIENTÍFICO INTERNACIONAL | INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC BOARD António Fidalgo (Universidade da Beira Interior, Portugal) Afonso Albuquerque (Universidade Federal Fluminense, Brasil) Alfredo Vizeu (Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Brasil) António Bento (Universidade da Beira Interior, Portugal) Barbie Zelizer (University of Pennsylvania, USA) Colin Sparks (University of Westminster, United Kingdom) Eduardo Camilo (Universidade da Beira Interior, Portugal) Eduardo Meditsch (Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Brasil) François Heinderyckx (Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgique) Elias Machado (Universidade Federal da Bahia, Brasil) Francisco Costa Pereira (Escola Superior de Comunicação Social, Portugal) Gil Ferreira (Universidade Católica Portuguesa) Helena Sousa (Universidade do Minho, Portugal) Javier Díaz Noci (Universidad del País Vasco, Espanã) Jean Marc-Ferry (Université Libre de Bruxelles, Institut d’Études Européennes, Belgique) João Pissarra Esteves (Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Portugal) João Canavilhas (Universidade da Beira Interior, Portugal) Joaquim Paulo Serra (Universidade da Beira Interior, Portugal) Jorge Pedro Sousa (Universidade Fernando Pessoa, Portugal) José Bragança de Miranda (Universidade Lusófona; Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Portugal) Manuel Pinto (Universidade do Minho, Portugal) Mark Deuze