Downloaded from National Election Watch ( Which Compiles Information from Affidavits Submitted by Candidates During the Nomination Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAHARASHTRA Not Mention PN-34

SL Name of Company/Person Address Telephone No City/Tow Ratnagiri 1 SHRI MOHAMMED AYUB KADWAI SANGAMESHWAR SANGAM A MULLA SHWAR 2 SHRI PRAFULLA H 2232, NR SAI MANDIR RATNAGI NACHANKAR PARTAVANE RATNAGIRI RI 3 SHRI ALI ISMAIL SOLKAR 124, ISMAIL MANZIL KARLA BARAGHAR KARLA RATNAGI 4 SHRI DILIP S JADHAV VERVALI BDK LANJA LANJA 5 SHRI RAVINDRA S MALGUND RATNAGIRI MALGUN CHITALE D 6 SHRI SAMEER S NARKAR SATVALI LANJA LANJA 7 SHRI. S V DESHMUKH BAZARPETH LANJA LANJA 8 SHRI RAJESH T NAIK HATKHAMBA RATNAGIRI HATKHA MBA 9 SHRI MANESH N KONDAYE RAJAPUR RAJAPUR 10 SHRI BHARAT S JADHAV DHAULAVALI RAJAPUR RAJAPUR 11 SHRI RAJESH M ADAKE PHANSOP RATNAGIRI RATNAGI 12 SAU FARIDA R KAZI 2050, RAJAPURKAR COLONY RATNAGI UDYAMNAGAR RATNAGIRI RI 13 SHRI S D PENDASE & SHRI DHAMANI SANGAM M M SANGAM SANGAMESHWAR EHSWAR 14 SHRI ABDULLA Y 418, RAJIWADA RATNAGIRI RATNAGI TANDEL RI 15 SHRI PRAKASH D SANGAMESHWAR SANGAM KOLWANKAR RATNAGIRI EHSWAR 16 SHRI SAGAR A PATIL DEVALE RATNAGIRI SANGAM ESHWAR 17 SHRI VIKAS V NARKAR AGARWADI LANJA LANJA 18 SHRI KISHOR S PAWAR NANAR RAJAPUR RAJAPUR 19 SHRI ANANT T MAVALANGE PAWAS PAWAS 20 SHRI DILWAR P GODAD 4110, PATHANWADI KILLA RATNAGI RATNAGIRI RI 21 SHRI JAYENDRA M DEVRUKH RATNAGIRI DEVRUK MANGALE H 22 SHRI MANSOOR A KAZI HALIMA MANZIL RAJAPUR MADILWADA RAJAPUR RATNAGI 23 SHRI SIKANDAR Y BEG KONDIVARE SANGAM SANGAMESHWAR ESHWAR 24 SHRI NIZAM MOHD KARLA RATNAGIRI RATNAGI 25 SMT KOMAL K CHAVAN BHAMBED LANJA LANJA 26 SHRI AKBAR K KALAMBASTE KASBA SANGAM DASURKAR ESHWAR 27 SHRI ILYAS MOHD FAKIR GUMBAD SAITVADA RATNAGI 28 SHRI -

Parivartan Yatra" in Saharanpur (Uttar Pradesh) Saturday, 05 November 2016

Salient Points of Speech by BJP National President, Shri Amit Shah Flagging Off "Parivartan Yatra" in Saharanpur (Uttar Pradesh) Saturday, 05 November 2016 Salient Points of the Speech of BJP National President Shri Amit Shah during Parivartan Yatra, Saharanpur In 2014, western Uttar Pradesh had laid the foundation of BJP’s spectacular victory in Lok Sabha elections. This time too, we are kick starting our campaign from western UP. The Parivartan Yatra, which will travel through the state and conclude on December 24, will lay the foundation for BJP’s two third majority in ensuing assembly elections. In 2014, the large hearted voters of Uttar Pradesh gave BJP 73 of 80 Lok Sabha seats that enabled us to form a full majority government at the centre. The approaching assembly elections of UP are crucial for the state’s future. In the last 15 years, it was either SP or BSP that formed the government and as a result, development in the state has completely stopped. If one wants to see development, he should visit villages in BJP ruled states. Each village has 24 hour power, ambulance reaches within 8 minutes, youth doesn’t have to migrate in search of jobs, and there is water in farmlands. Uttar Pradesh has become a laggard on the development index and those responsible for progress of the state are fighting among themselves. Uncle (Shivpal Yadav) is abusing his nephew (Akhilesh Yadav) and vice versa while aunt (Mayawati) is abusing both. None of them are bothered about development. Neither SP or BSP can bring development in the state. -

7. from Democracy to Kleptocracy

Outlook Saurabh Singh/ From Democracy to Kleptocracy Extracts from the Affidavit Submitted to the Venkatswamy Commission by Prem Shankar Jha ...The Tehelka tapes provided State Trading Corporation of India being spent on each election even the first incontrovertible, visual for refund of kickbacks amounting as elections themselves became proof of what was common to $6 million, on three contracts to more and more frequent, as the knowledge among journalists and purchase sugar from it, for a total stability of governments diminished, others involved in public affairs that sum of $45 million, that the STC had and especially after the separation agents continued to operate as dishonoured. In 1987 we received of Central from State elections in intermediaries in defence contracts, the first incontrovertible evidence 1971. But there was no legally and that kickbacks on Defence and, of kickbacks in the Bofors gun and permissible method for raising more by inference other foreign contracts HDW submarine deals. These were than a tiny fraction of the sums that had become one of the principal the high points that, seen against were being spent. Where was the methods of meeting the need of the backdrop of periodic reports of rest of the money coming from?... political parties for funds to fight the Comptroller and Auditor- The root of the all-pervasive elections and to meet their running General’s (CAG’s) office, made me corruption exposed by Tehelka lies expenses. conclude that the cloud of in a lacuna in the Indian Constitution. Till March 13 this year the assertions, rumours and gossip This is the lack of any provision evidence available had been indirect about kickbacks on virtually every for meeting the cost of running a and inferential. -

Mau Violence

An Exclusive Citizens Report MAU RIOTS: A REPORT Introduction: There is a lot of confusion in the media and at socio-political levels about the communal tension and widespread violence that began in Mau on October 13-14, 2005. Consequently, “Saajhi Duniya” considered it necessary to visit Mau and acquaint itself with the real situation. The first team from Saajhi Duniya visited Mau on October 20, when the city was under total curfew. Again on October 30 and 31, representatives of Saajhi Duniya went to Mau. This team comprised Prof. Roop Rekha Verma (social activist and secretary, Saajhi Duniya), Mr Vibhuti Narain Rai (president, Saajhi Duniya, litterateur and activist on issues related to communalism) and Mr Nasiruddin Haider Khan (journalist). Mr Jai Parkash Dhumketu (litterateur and activist) from Mau also joined the group. This team not only visited the riot-affected areas in Mau but also inquired into the causes of the violence. The team spoke to victims of the violence, social and political workers, the general public and officers of the district administration. The following report is the outcome of our efforts, over three days, to understand the recent riots in Mau. Mau (also called Maunath Bhanjan) has always been a communally sensitive district. Previously a part of Azamgarh, Maunath Bhanjan witnessed periodic bouts of communal violence every few years. The population of Mau is 18,53,997 with an urban population of 3,60,369 and a rural population of 14,93,628. Within this population, around 80.5 per cent are Hindus, out of which 90 per cent of the population is rural and approximately 10 per cent is urban. -

Transparency Issue April 3.Qxd

Volume II, No. 2 May-June 2007 Transparency Review Journal of Transparency Studies, Centre for Media Studies (CMS) MAYAWATI DEBUNKS MEDIA CONTENTS U.P. Assembly Elections The Chairman of Centre for Media Studies effectively (1) Mayawati Debunks Media, Money & demolishes the pre-election myth of the might of money, Muscle Power musclemen and the media in the success or failure of the (Dr. N. Bhaskar Rao) -3 respective political parties (2) Silent Revolution in U.P The author analyses the results and pinpoints certain (Mr. Bhibhu Mohapatra) -5 notably distinct features in this election (3) Crime and Punishment Reports in the media on some of the interesting aspects (Transparency Studies) -7 relating to parties and contestants. (4) Five-Star Jails in India The Former Director, CBI says politicians in some of (Mr. Joginder Singh) -12 the jails enjoy all the comforts of a home, making a mockery of their supposed incarceration RIGHT TO INFORMATION Implementation Research Needed Reviewing the working of the RTI, the author concludes, (Dr. N. Bhaskar Rao) -14 with some hard facts, that there is an urgent need to undertake research on the whole gamut of the Act in the light of the two-year experience on the ground On a petition seeking to view documents relating to the Ansari’s Appointment appointment of one of the Central Commissioners, the (Transparency Studies) -16 CIC left it to the Prime Minister’s Office to decide the petition in the light of its earlier orders on similar issues CIC Briefs -17 Some Reports on CIC desicions and court interventions Editor: Ajit Bhattacharjea CEC Protects Dalits Against Bahubalis utting this issue together has proved shock perhaps because they are conveyed a fascinating learning experience. -

No End to Crimes Against Dalits

www.openthemagazine.com 50 12 OCTOBER /2020 OPEN VOLUME 12 ISSUE 40 12 OCTOBER 2020 CONTENTS 12 OCTOBER 2020 5 6 8 14 16 18 22 28 LOCOMOTIF INDRAPRASTHA MUMBAI TOUCHSTONE SOFT POWER WHISPERER IN MEMORIAM OPEN ESSAY The House of By Virendra Kapoor NOTEBOOK The sounds of our The Swami and the By Jayanta Ghosal Jaswant Singh Is it really over Jaswant Singh By Anil Dharker discontents Himalayas (1938-2020) for Trump? By S Prasannarajan By Keerthik Sasidharan By Makarand R Paranjape By MJ Akbar By James Astill and TCA Raghavan 32 32 BROKEN BOLLYWOOD Divided, self-referential in its storytelling, all too keen to celebrate mediocrity, its reputation in tatters and work largely stalled, the Mumbai film industry has hit rock bottom By Kaveree Bamzai 40 GRASS ROOTS Marijuana was not considered a social evil in the past and its return to respectability is inevitable in India By Madhavankutty Pillai 44 THE TWILIGHT OF THE GANGS 40 Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath has declared war on organised crime By Virendra Nath Bhatt 22 50 STATECRAFT Madhya Pradesh’s Covid opportunity By Ullekh NP 44 54 GLITTER IN GLOOM The gold loan market is cashing in on the pandemic By Nikita Doval 50 58 62 64 66 BETWEEN BODIES AND BELONGING MIND AND MACHINE THE JAISHANKAR DOCTRINE NOT PEOPLE LIKE US A group exhibition imagines Novels that intertwine artificial Rethinking India’s engagement Act two a multiplicity of futures intelligence with ethics with its enemies and friends By Rajeev Masand By Rosalyn D’Mello By Arnav Das Sharma By Siddharth Singh Cover by Saurabh Singh 12 OCTOBER 2020 www.openthemagazine.com 3 OPEN MAIL [email protected] EDITOR S Prasannarajan LETTER OF THE WEEK MANAGING EDITOR PR Ramesh C EXECUTIVE EDITOR Ullekh NP By any criterion, 2020 is annus horribilis (‘Covid-19: The EDITOR-AT-LARGE Siddharth Singh DEPUTY EDITORS Madhavankutty Pillai Surge’, October 5th, 2020). -

Muslim Legislators of Uttar Pradesh

The Hindu Centre for Politics and Public Policy is a division of Kasturi & Sons Ltd., publishers of The Hindu and group newspapers. It was inaugurated by the President of India, Pranab Mukherjee on January 31, 2013. The aim of The Hindu Centre is to promote research, dialogue and discussion to enable the creation of informed public opinion on key issues facing India to safeguard, strengthen and nourish parliamentary democracy and pluralism, and to contribute to the nation’s economic, social and political betterment. In accordance with this mission, The Hindu Centre publishes Policy Reports drawing upon the research of its scholars, to explain and highlight issues and themes relating to political affairs and public policy. These are intended to aid the public in making informed judgments on issues of public importance. The Hindu Centre publishes the Policy Reports online, and can be accessed at www.thehinducentre.com/publications/policy-report/ Published by: The Hindu Centre for Politics and Public Policy, 859&860, Anna Salai, Chennai 600002, [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the publisher. The Phenomenon of Political Dynasties Among the Muslim Legislators of Uttar Pradesh Mohd Osama Public Policy Scholar, The Hindu Centre for Politics and Public Policy (February – May, 2018) --- ABSTRACT his report on the phenomenon of political dynasties among Muslims in Uttar Pradesh is an empirical enquiry into the extent it has impacted the legislature. The report bases T its findings in the fieldwork conducted in Uttar Pradesh to determine the dynastic credentials of Muslim legislators over the last two decades, and finds that the more marginalised a community, the larger the number of political dynasties it will have in the Legislature. -

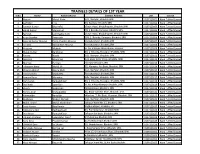

TRAINEES DETAILS of 1ST YEAR S.No Name Fathers Name Contact Address UID Course 1 Naeem Mohd

TRAINEES DETAILS OF 1ST YEAR S.No Name Fathers Name Contact Address UID Course 1 Naeem Mohd. Yasin 122, Alampur, Bhadohi SRN 0107120101 Hand Tuffted Carpet 2 Saif Khan Firoj 63, Kashipur Bhadohi SRN 0107120102 Hand Tuffted Carpet 3 Santosh Kumar DharmRaj Chauri Road, Bhuddhapatti, Bhadohi SRN 0107120103 Hand Tuffted Carpet 4 Satish Kumar Munna Lal 78, 1-Revada Paraspur, Bhadohi SRN. 0107120104 Hand Tuffted Carpet 5 Ramesh Late Raghu Nath Chauri Road, Bhuddhapatti, Bhadohi SRN 0107120105 Hand Tuffted Carpet 6 Kripa Shanker Amarnath 183, 1- Revada, Paraspur, Bhadohi, SRN 0107120106 Hand Tuffted Carpet 7 Sravesh Kumar Maurya Prem Chandra Maurya Pureshyampur,Bhadohi,SRN 0107120107 Hand Tuffted Carpet 8 Ari Devi Baboo Ram Maurya Pureshyampur,Bhadohi,SRN 0107120108 Hand Tuffted Carpet 9 Haseena Mehtab H. No. 8 Rayan Madiyahuan, Jaunpur. 0107120109 Hand Tuffted Carpet 10 Manoj Kumar Ramkaran 40, 1- Revada, Paraspur, Bhadohi, SRN. 0107120110 Hand Tuffted Carpet 11 Farooq Wazid 181, Alampur, Bhadohi, SRN. 0107120111 Hand Tuffted Carpet 12 Nand Lal Bharat Lal 141, Bajar Srdar Khan, Bhadohi, SRN 0107120112 Hand Tuffted Carpet 13 Mumtaj Furman Alampur,Bhadohi,SRN 0107120113 Hand Tuffted Carpet 14 Tabassum Bano Mohd. Sfi 95, Alampur, Nai Basti, Bhadohi, SRN. 0107120114 Hand Tuffted Carpet 15 Wakeel Ahmad Amina Shah 144, Alampur, Bhadohi, SRN. 0107120115 Hand Tuffted Carpet 16 Fool chandra Shankatha Pureshyampur,Bhadohi,SRN 0107120116 Hand Tuffted Carpet 17 Aimana Bano Mumataz 106, Alampur, Bhadohi, SRN. 0107120117 Hand Tuffted Carpet 18 Ram Karan Ramaabhilash 40, 1- Revada, Paraspur, Bhadohi, SRN. 0107120118 Hand Tuffted Carpet 19 Shri Nath Jagar Dev H. No. 4 Noorkhanpur Bhadohi, SRN. -

The Supreme Court of India Civil Original Jurisdiction Writ Petition (Crl.) No

THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION WRIT PETITION (CRL.) NO. 409 OF 2020 IN THE MATTER OF: STATE OF UTTAR PRADESH …. PETITIONER VERSUS JAIL SUPERINTENDENT (ROPAR) & ORS. …. RESPONDENTS INDEX SR. PARTICULARS PAGE NOS. NO. 1. Written Submissions on behalf of the Petitioner 1-23 DRAWN AND FILED BY: [GARIMA PRASHAD] Standing Counsel- State of U.P. B-10, Green Park Extension New Delhi-110016 FILED ON: 23.02.2021 PLACE: NEW DELHI THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA 1 CIVIL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION WRIT PETITION (CRL.) NO. 409 OF 2020 IN THE MATTER OF: STATE OF UTTAR PRADESH …. PETITIONER VERSUS JAIL SUPERINTENDENT (ROPAR) & ORS. …. RESPONDENTS WRITTEN SUBMISSIONS ON BEHALF OF THE PETITIONER A. BRIEF FACTUAL BACKGROUND: Criminal Trial is pending against the accused Respondent No.3 in ten heinous cases of murder, extortion, cheating, fraud, gangster acts being Case Crime Nos. 399/2010, 891/2020, 1182/2009, 1051/2007, 263/1990, 337/1997, 229/1991, 482/2010, 192/1996 and 20/2014 at the Special Court (MP/MLA) at Allahabad constituted by the Hon’ble Allahabad High Court. The Ld. Special Judge (MP/MLA) ordered to incarcerate Respondent No.3, in District Jail, Banda, U.P. so that Respondent No.3 could be produced before the Court on every date in each case ensuring that the criminal prosecution against Respondent No.3 who is a sitting MLA be concluded expeditiously. 2 In connection to Case Crime No. 05 of 2019 under Sections 386 and 506 IPC registered at Police Station Mathaur, District Mohali, State of Punjab on 08.01.2019, the Learned Judicial Magistrate-I Mohali issued a production warrant under Section 267of the Code of Criminal Procedure. -

Doctor of Philosophy in POLITICAL SCIENCE

BACKWARD CASTE MOVEMENT IN UTTAR PRADESH: STUDY OF SAMAJWADI PARTY THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy IN POLITICAL SCIENCE BY RAJMOHAN SHARMA UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. NIGAR ZUBERI DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH-202002 (INDIA) 2016 Prof. Nigar Zuberi Extension :( 0571) 2701720 Department of Political Science, Internal: 1560 Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh - 20 2002 (U.P.) India. Dated ………………… Certificate This is to certify that Mr. Rajmohan Sharma, Research Scholar, Department of Political Science, A.M.U., Aligarh has completed his Ph.D. thesis entitled “Backward Caste Movement in Uttar Pradesh: Study of Samajwadi Party ” under my supervision. The data materials, incorporated in the thesis have been collected from various sources. The researcher used and analyzed the aforesaid data and material systematically and presented the same with pragmatism. To the best of knowledge and understanding a faithful record of original research work has been carried out. This work has not been submitted partially or fully for any degree or diploma in Aligarh Muslim University or any other university. He is permitted to submit the thesis. I wish him all success in life. (Prof. Nigar Zuberi) Acknowledgement I thank to the Almighty for His great mercifulness and choicest blessings generously bestowed on me without which I could have never seen this work through. First of all, I would like to express the most sincere thanks and profound sense of gratitude to my supervisor Prof. Nigar Zuberi for her continuous support, valuable suggestions and constant encouragement in my Ph.D. work. I am deeply obliged for her motivation, enthusiasm and inspiration during the course of Ph.D. -

Lodna Area-X

Bharat Coking Coal Limited (A Subsidiary of Coal India Limited) Page No. Area:- Lodna -X, Unit:- Bararee coliiery, Colony:- Laxmi Colony Status as on LIST OF OCCUPANTS OF QUARTERS OF BCCL Place of working in If allotted to person other Designation & Personnel No. Whether Authorised SN Qtr. No. Type of Qtr. Name of Occupant case of BCCL than BCCL employees on Remarks if BCCL employee on rolls or unauthorised employee on rolls rolls. Details thereof 1 NA BLOCK-01//1 2 NA 1 Damaged N/A N/A N/A 3 NA 2 Damaged N/A N/A N/A N/A 4 NA 3 GOPAL privet N/A N/A UNAUTHORISED 5 NA 4 VACANT N/A N/A N/A N/A 6 NA 5 VACANT N/A N/A N/A N/A 7 NA 6 VACANT N/A N/A N/A N/A BLOCK-2 8 NA 1 RAJESH singh privet N/A N/A N/A 9 NA 2 AMRIT RAJBHAR Trammer 02750628 Bararee AUTHORISED 10 NA 3 Umashankar Ravidas privet N/A N/A UNAUTHORISED 11 NA 4 VACANT N/A N/A N/A N/A 12 NA 5 Dinesh Saw privet N/A N/A UNAUTHORISED 13 NA 6 Rajdeo Bhar privet N/A N/A UNAUTHORISED 14 NA 7 Dhamu pasawan privet N/A N/A UNAUTHORISED 15 NA 8 VACANT&DAMAGED N/A N/A N/A N/A BLOCK-3 16 NA 1 Brajesh Singh privet N/A N/A UNAUTHORISED 17 NA 2 Budhan Ram privet N/A N/A UNAUTHORISED 18 NA 3 Manoj Pasawan privet N/A N/A UNAUTHORISED 19 NA 4 Sunil Bauri privet N/A N/A UNAUTHORISED 20 NA 5 Ramesh Thakur privet N/A N/A UNAUTHORISED BLOCK-4 21 NA 1 Dhamu Pasawan Privet N/A N/A UNAUTOHRISED 22 NA 2 Birsha Munda Privet N/A N/A UNAUTHORISED 23 NA 3 Ashok Sharma Privet N/A N/A UNAUTHORISED 24 NA 4 VACANT Privet N/A N/A UNAUTHORISED 25 NA 5 Parwati kumari S/Guard 02793917 Bararee AUTHORISED 26 NA 6 VACANT N/A N/A N/A N/A 27 NA 7 Tinku Privet N/A N/A UNAUTHORISED 28 NA 8 VACANT N/A N/A N/A N/A BLOCK-5 29 NA 1 Tetari Devi Privet N/A N/A UNAUTHORISED 30 NA BLOCK-6/1 Bhikhari Saw Privet N/A N/A UNAUTHORISED 31 NA 2 VACANT NA N/A N/A N/A 32 NA 3 Subhash Sahis Privet N/A N/A UNAUTHORISED 33 NA 4 VACANT N/A N/A N/A N/A 34 NA 5 VACANT N/A N/A N/A N/A 35 NA 6 Awdhesh Yadav Privet N/A N/A UNAUTHROISED 36 NA 7 Sadhu Pasi Privet N/A N/A UNAUTHORISED 37 NA 8 VACANT N/A N/A N/A N/A 38 NA 9 Rajesh KR. -

RASHTRIYA SAHARA, Lucknow, 18.5.2021 Page No

RASHTRIYA SAHARA, Lucknow, 18.5.2021 Page No. 07, Size:(10.78)cms X (12.59)cms. ANI, Online, 18.5.2021 Page No. 0, Size:(0)cms X (0)cms. Delhi HC issues notice on plea of slum-dwellers, homeless people for food, shelter, financial help https://www.aninews.in/news/national/general-news/delhi-hc-issues-notice-on-plea-of- slum-dwellers-homeless-people-for-food-shelter-financial-help20210517125754/ The Delhi High Court on Monday issued notice on a plea of slum dwellers and homeless people, who sought direction to the Central Government, National Human Rights Commission of India (NHRC), Delhi government, Delhi police and other authorities to make adequate arrangements for their food, shelter, financial help, and employment skills and to provide them with ration cards, labour cards or other beneficiary cards for them. The bench of Justice DN Patel and Justice Jyoti Singh sought a response from all the respondents and adjourned the matter for June 4. Around six people, who are slum dwellers, homeless and belong to the poor section of the society with the help of two law students, had moved the Public Interest Litigation (PIL) and sought direction to NHRC, National Commission for protection of children rights, Delhi commission for protection of children rights, Delhi urban shelter improvement board, Delhi state legal service authority for an instant detailed survey of numbers of street dwellers, homeless, beggars across Delhi and direct the Government of NCT of Delhi to form a permanent committee to look after these people from time to time. The petitioners also sought direction for arrangement by creating community kitchens and provide quality food three times a day in their hands and make proper mechanisms for distribution.