Doctor of Philosophy in POLITICAL SCIENCE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allahabad Division)-2018

List of Sixteen Lok Sabha- Members (Allahabad Division)-2018 S. Constituency/ Name of Member Permanent Address & Mobile No. Present N. Party Address & Mobile No. 1 CNB/BJP Dr. Murli Manohar Joshi 9/10-A tagore Nagar, Anukul 6, Raisina Road. New Chandra Banerjee Road, Allahabad- Delhi-110001 211002,(UP) Tel.No. (011) C/O Mr. Lalit Singh, 15/96 H Civil 23718444, 23326080 Lines, Kanpur-208001 Phone No. 0512-2399555 2 ALD/BJP Sri Shyama Charan Gupta. 44- Thornhill Road, Allahabad A-5, Gulmohar Park, .211002 (U.P) Khelgaon Road, New Ph.N0. (0532)2468585 & 86 Delhi-110049 Mob.No. 09415235305(M) Fax.N. (0532)2468579 Tels. No.(011)26532666, 26527359 3 Akbarpur Sri Devendra Singh Bhole 117/P/17 Kakadev, Kanpur (CNB/Dehat)/ Mob No.9415042234 BJP Tel. No. 0512-2500021 4 Rewa/BJP Sri Janardan Mishra Villagae & Post- Hinauta Distt.- Rewa Mob. No.-9926984118 5 Chanduli/BJP Dr. Mahendra Nath Pandey B 22/157-7, Sarswati Nagar New Maharastra Vinayaka, Distt.- Varanasi (UP) Sadan Mob. No. 09415023457 K.G. Marg, New Delhi- 110001 6 Banda/BJP Sri Bhairon Prasad Mishra Gandhiganj, Allahabad Road Karvi, Distt.-Chitrakut Mob. No.-09919020862 7 ETAH/BJP Sri Rajveer Singh A-10 Raj Palace, Mains Road, Ashok Hotel, (Raju Bhaiya) Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh Chankayank Puri New (0571) 2504040,09457011111, Delhi-110021 09756077777(M) 8 Gautam Buddha Dr. Mahesh Sharma 404 Sector- 15-A Nagar/BJP Noida-201301 (UP) Tel No.(102)- 2486666, 2444444 Mob. No.09873444255 9 Agra/BJP Dr. Ram Shankar Katheriya 1,Teachers home University Campus 43, North Avenue, Khandari, New Delhi-110001 Agra-02 (UP) Mob. -

List of OBC Approved by SC/ST/OBC Welfare Department in Delhi

List of OBC approved by SC/ST/OBC welfare department in Delhi 1. Abbasi, Bhishti, Sakka 2. Agri, Kharwal, Kharol, Khariwal 3. Ahir, Yadav, Gwala 4. Arain, Rayee, Kunjra 5. Badhai, Barhai, Khati, Tarkhan, Jangra-BrahminVishwakarma, Panchal, Mathul-Brahmin, Dheeman, Ramgarhia-Sikh 6. Badi 7. Bairagi,Vaishnav Swami ***** 8. Bairwa, Borwa 9. Barai, Bari, Tamboli 10. Bauria/Bawria(excluding those in SCs) 11. Bazigar, Nat Kalandar(excluding those in SCs) 12. Bharbhooja, Kanu 13. Bhat, Bhatra, Darpi, Ramiya 14. Bhatiara 15. Chak 16. Chippi, Tonk, Darzi, Idrishi(Momin), Chimba 17. Dakaut, Prado 18. Dhinwar, Jhinwar, Nishad, Kewat/Mallah(excluding those in SCs) Kashyap(non-Brahmin), Kahar. 19. Dhobi(excluding those in SCs) 20. Dhunia, pinjara, Kandora-Karan, Dhunnewala, Naddaf,Mansoori 21. Fakir,Alvi *** 22. Gadaria, Pal, Baghel, Dhangar, Nikhar, Kurba, Gadheri, Gaddi, Garri 23. Ghasiara, Ghosi 24. Gujar, Gurjar 25. Jogi, Goswami, Nath, Yogi, Jugi, Gosain 26. Julaha, Ansari, (excluding those in SCs) 27. Kachhi, Koeri, Murai, Murao, Maurya, Kushwaha, Shakya, Mahato 28. Kasai, Qussab, Quraishi 29. Kasera, Tamera, Thathiar 30. Khatguno 31. Khatik(excluding those in SCs) 32. Kumhar, Prajapati 33. Kurmi 34. Lakhera, Manihar 35. Lodhi, Lodha, Lodh, Maha-Lodh 36. Luhar, Saifi, Bhubhalia 37. Machi, Machhera 38. Mali, Saini, Southia, Sagarwanshi-Mali, Nayak 39. Memar, Raj 40. Mina/Meena 41. Merasi, Mirasi 42. Mochi(excluding those in SCs) 43. Nai, Hajjam, Nai(Sabita)Sain,Salmani 44. Nalband 45. Naqqal 46. Pakhiwara 47. Patwa 48. Pathar Chera, Sangtarash 49. Rangrez 50. Raya-Tanwar 51. Sunar 52. Teli 53. Rai Sikh 54 Jat *** 55 Od *** 56 Charan Gadavi **** 57 Bhar/Rajbhar **** 58 Jaiswal/Jayaswal **** 59 Kosta/Kostee **** 60 Meo **** 61 Ghrit,Bahti, Chahng **** 62 Ezhava & Thiyya **** 63 Rawat/ Rajput Rawat **** 64 Raikwar/Rayakwar **** 65 Rauniyar ***** *** vide Notification F8(11)/99-2000/DSCST/SCP/OBC/2855 dated 31-05-2000 **** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11677 dated 05-02-2004 ***** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11823 dated 14-11-2005 . -

4. the Freedom Struggle of 1857

4. The Freedom Struggle of 1857 In 1857, a great struggle took place in India which completely shook the British Government. This struggle did not arise all of a sudden. Earlier as well many such struggles took place in India against the British. The scope of the struggle of 1857 and its background was taken into consideration by V.D.Savarkar in his book ‘The Indian War of Independence 1857’. Later many revolutionaries got inspiration from it to fight against the British. Struggle before 1857 : At every place where the British rule was established in India, the local people had to bear the ill effects of British government. The Indians started feeling that they are exploited in every strata due to the company's rule. This resulted in increase of discontent against their rule. For your information Paika Rebellion : From mediaeval times, there was a system of Paikas existing in Odisha. The standing army of various independent kings were known as ‘Paika’. Rent free lands were granted to them for cultivation by the king. The Paikas earned their livelihood through it. In return, they were supposed to stand by the king’s side in case of eruption of war. In 1803, the English conquered Odisha. They took over the hereditary rent free lands granted to the Paikas. This made the Paikas angry. Similarly, common man’s life had also become miserable because of rise in salt price due to tax imposed on it by the British. This resulted in an armed rebellion of Paikas against the British in 1817. Bakshi Jaganbandhu Bidyadhar led this revolt. -

Dr. Bhagat Singh Biography by Chapman

Doctorji: An Exhibit on the Life of Dr. Bhagat Singh Thind Exhibit Dates: November 17, 2016 – January 15, 2016 Dr. Bhagat Singh Thind was born on October 3, 1892 into a well-known military Kamboj Sikh Thind family in the village Taragarh/Talawan in District Amritsar, Punjab. His father S. Buta Singh Thind was retired as a Subedar Major from the British Indian Army. His mother Icer Kaur died when Dr. Thind was only a child, but left an indelible mark on him. Dr. Thind’s ancestors had served in the Sikh army of Maharaja Ranjit and before that, in the Marjeewra Sikh fauj of the 10th Lord and earned a reputation as a warrior family. S. Buta Singh Thind and his family and relations were very dedicated Sikhs and actively participated in Sikh Morcha for possession of lands belonging to Gurudwara Pheru, at Lahore in 1924 and earlier in Nankana Sahib Morcha in 1921, where out of eighty-six Singh Shaheeds, thirty-two were the Kamboj Singhs. S. Buta Singh Thind was jailed for several years and lost his military pension as a consequence. In this Gurudwara Morcha, S. Buta Singh also persuaded several other Kamboj Singhs, if Shekhupuru, to actively participate in the movement. Dr. Bhagat Singh Thind had clearly inherited his love for Sikhism and humanity from his devoted Sikh parents and relatives. After his high school graduation in 1908, Dr. Thind attended Khalsa College, Amritsar and obtained his College Degree. While a student at Khalsa College, Dr. Thind studied American history and the literature of Emerson, Whitman, and Thoreau. -

Rapid Behaviour Assessment and Ranking of PRI Members, Natural and Faith Based Leaders and Dipstick Assessment of ASHA, Anganwadi Workers

Rapid Behaviour assessment and ranking of PRI members, Natural and faith based leaders And Dipstick assessment of ASHA, Anganwadi workers Bihar and Uttar Pradesh 1 Febr16 Table of Contents Executive Summary Key Recommendations 1. Background 1.1 Programme: A brief description on intervention, geography, school settings 1.2 Objectives of the study 2. Methodology 2.1 Sample size calculation 3. Data collection and tools 3.1 Training of teams 3.2 Ensuring data quality 4. Socio Demographic Profile Go to Table of Contents 2 Executive Summary The aim of the study is to assess the behaviour and knowledge of the PRI members and ASHA Angadawadi workers on issues such as open defecation and hand washing practices and also their awareness about the Swach Bharat Program of the Indian Government. For the purpose of the Study, a survey was carried out in 4 Districts of UP and Bihar in which respondents from over 201 villages were interviewed. Amongst the ASHA and Angadwadi workers, almost all have received some sort of formal education and also hygiene training and all of them are house makers. On the other side, primary occupation of most of the PRI members is farming with very less in business and self- employment. When asked about the time given by these workers and leaders in interacting and solving issues of the fellow villagers, over 57% in Bihar and 52% in UP said to devote somewhere between 1 to 2 hours every day. In the survey conducted, lack of proper facilities was founded to be the major reason behind open defecation with more than 75% of the respondents in both states saying so. -

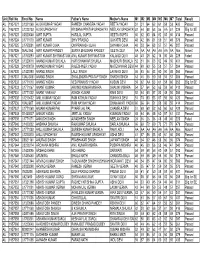

Unit Roll No Enrol No Name Father's Name Mother's Name M1 M2 M3 M4 M5 M6 M7 Total Result AU 1957021 U1321068 ALOK KUMAR YADAV RA

Unit Roll No Enrol No Name Father's Name Mother's Name M1 M2 M3 M4 M5 M6 M7 Total Result AU 1957021 U1321068 ALOK KUMAR YADAV RAMESH CHANDRA YADAV REETA YADAV 51 51 64 62 61 58 53 400 Passed AU 1957022 U1223703 ALOK UPADHYAY KRISHNA PRATAP UPADHYAY NEELAM UPADHYAY52 44 58 63 56 AA 51 324 Elig.for SE AU 1957023 U0820048 AMIT GUPTA HARILAL GUPTA GEETA GUPTA 60 52 63 64 62 53 60 414 Passed AU 1957024 U1771070 AMIT KUMAR SHIV PRASAD GAYATRI DEVI 48 42 66 61 59 51 49 376 Passed AU 1957025 U1760291 AMIT KUMAR OJHA OM PRAKASH OJHA SHYAMA OJHA 48 53 64 63 57 57 45 387 Passed AU 1957026 05AU/363 AMIT KUMAR PANDEY SURYA BHUSHAN PANDEY GEETA DEVI AA AA AA AA AA AA AA Abs Absent AU 1957027 U1760293 AMIT KUMAR SHRIWASTAW ANIL KUMAR SHRIWASTAW KALANDI DEVI 48 40 29 52 15 00 45 229 Failed AU 1957028 U1320016 ANAND KUMAR SHUKLA HARI SHANKAR SHUKLA MADHURI SHUKLA 52 51 64 63 62 49 60 401 Passed AU 1957029 D1430079 ANAND KUMAR YADAV RAJESHWER YADAV MATESHWARI DEVI 44 60 63 55 58 57 57 394 Passed AU 1957030 U1420380 ANAND SINGH LALJI SINGH LAVANGI DEVI 46 63 54 43 60 50 48 364 Passed AU 1957031 13AU/3081 ANAND SINGH SHAILENDRA PRATAP SINGH SHASHI SINGH 63 48 55 50 58 55 57 386 Passed AU 1957032 U1771010 ANAND YADAV VED PRAKASH YADAV KUSUM DEVI 59 62 AA 53 61 58 60 353 Elig.for SE AU 1957033 U1771067 ANANT KUMAR ARVIND KUMAR MISHRA SHALINI MISHRA 54 57 64 53 65 59 60 412 Passed AU 1957034 U1771002 ANANT VABHAV ASHOK KUMAR RANI DEVI 52 64 60 57 53 48 50 384 Passed AU 1957035 U1210432 ANIL KUMAR YADAV RAM KISHUN YADAV SUKHIYA DEVI 51 70 63 53 67 56 60 420 Passed -

Astavarga Plants- Threatened Medicinal Herbs of the North-West Himalaya

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312533047 Astavarga plants- threatened medicinal herbs of the North-West Himalaya Article · January 2012 CITATIONS READS 39 714 8 authors, including: Anupam Srivastava Rajesh Kumar Mishra Patanjali Research Institute Patanjali Bhartiya Ayurvigyan evum Anusandhan Sansthan 16 PUBLICATIONS 40 CITATIONS 43 PUBLICATIONS 84 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Rajiv K. Vashistha Dr Ajay Singh Hemwati Nandan Bahuguna Garhwal University Patanjali Bhartiya Ayurvigyan Evam Anusandhan Sansthan Haridwar 34 PUBLICATIONS 216 CITATIONS 5 PUBLICATIONS 79 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: ANTI FUNGAL ACTIVITY OF GANDHAK DRUTI AND GANDHAKADYA MALAHAR View project Invivo study of Roscoea purpurea View project All content following this page was uploaded by Rajesh Kumar Mishra on 10 September 2019. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Int. J. Med. Arom. Plants, ISSN 2249 – 4340 REVIEW ARTICLE Vol. 2, No. 4, pp. 661-676, December 2012 Astavarga plants – threatened medicinal herbs of the North-West Himalaya Acharya BALKRISHNA, Anupam SRIVASTAVA, Rajesh K. MISHRA, Shambhu P. PATEL, Rajiv K. VASHISTHA*, Ajay SINGH, Vikas JADON, Parul SAXENA Patanjali Ayurveda Research and Development Department, Patanjali Yogpeeth, Maharishi Dayanand Gram, Near Bahadrabad, Haridwar- 249405, Uttarakhand, India Article History: Received 24th September 2012, Revised 20th November 2012, Accepted 21st November 2012. Abstract: Astavarga eight medicinal plants viz., Kakoli (Roscoea purpurea Smith), Kshirkakoli (Lilium polyphyllum D. Don), Jeevak (Crepidium acuminatum (D. Don) Szlach), Rishbhak (Malaxis muscifera (Lindl.) Kuntze), Meda (Polygonatum verticillatum (Linn.) Allioni), Mahameda (P. -

The State We Are In

THE STATE WE ARE IN Dr. N.L. Dongre THE shocking incident of the beating and molestation of a young woman by a mob in Guwahati in Assam on July 9 has exposed the ugly underbelly of modern, globalised India, where women face violence, covertly and overtly, at home and outside. The incident has also exposed the lackadaisical manner in which these crimes are treated by the authorities and the general public, and subjected to all kinds of interpretations, which eventually deflects attention from the real issues behind the violent manifestation of and escalation in such crimes. It was not long ago, in June, that Rumi Nath, a young woman legislator of the ruling Congress in Assam, was beaten up by a mob just because she had dared to marry for the second time. In another case, a woman Member of Parliament from Dahod in Gujarat was beaten up by the police. The Guwahati incident attracted significant public attention, widely telecast as it was on the days following it and later repeatedly shown on leading television channels and social networking sites as a subject matter of discussion. How much of this was voyeuristic is anybody's guess. The focus shifted from the victim and the overall situation of rising crimes against women to the role of the media, the electronic media in particular, and the clumsy handling of the case by the National Commission for Women (NCW), a statutory body set up nearly two decades ago to strengthen the legal apparatus to protect women. 1 The NCW, which has assumed the role of a proactive body over the last one decade in terms of conducting several fact-finding and inquiry committees into random incidents of violence against women, went into mission mode after the Guwahati incident. -

List of Successful Candidates

11 - LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 1 Nagarkurnool Dr. Manda Jagannath INC 2 Nalgonda Gutha Sukender Reddy INC 3 Bhongir Komatireddy Raj Gopal Reddy INC 4 Warangal Rajaiah Siricilla INC 5 Mahabubabad P. Balram INC 6 Khammam Nama Nageswara Rao TDP 7 Aruku Kishore Chandra Suryanarayana INC Deo Vyricherla 8 Srikakulam Killi Krupa Rani INC 9 Vizianagaram Jhansi Lakshmi Botcha INC 10 Visakhapatnam Daggubati Purandeswari INC 11 Anakapalli Sabbam Hari INC 12 Kakinada M.M.Pallamraju INC 13 Amalapuram G.V.Harsha Kumar INC 14 Rajahmundry Aruna Kumar Vundavalli INC 15 Narsapuram Bapiraju Kanumuru INC 16 Eluru Kavuri Sambasiva Rao INC 17 Machilipatnam Konakalla Narayana Rao TDP 18 Vijayawada Lagadapati Raja Gopal INC 19 Guntur Rayapati Sambasiva Rao INC 20 Narasaraopet Modugula Venugopala Reddy TDP 21 Bapatla Panabaka Lakshmi INC 22 Ongole Magunta Srinivasulu Reddy INC 23 Nandyal S.P.Y.Reddy INC 24 Kurnool Kotla Jaya Surya Prakash Reddy INC 25 Anantapur Anantha Venkata Rami Reddy INC 26 Hindupur Kristappa Nimmala TDP 27 Kadapa Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy INC 28 Nellore Mekapati Rajamohan Reddy INC 29 Tirupati Chinta Mohan INC 30 Rajampet Annayyagari Sai Prathap INC 31 Chittoor Naramalli Sivaprasad TDP 32 Adilabad Rathod Ramesh TDP 33 Peddapalle Dr.G.Vivekanand INC 34 Karimnagar Ponnam Prabhakar INC 35 Nizamabad Madhu Yaskhi Goud INC 36 Zahirabad Suresh Kumar Shetkar INC 37 Medak Vijaya Shanthi .M TRS 38 Malkajgiri Sarvey Sathyanarayana INC 39 Secundrabad Anjan Kumar Yadav M INC 40 Hyderabad Asaduddin Owaisi AIMIM 41 Chelvella Jaipal Reddy Sudini INC 1 GENERAL ELECTIONS,INDIA 2009 LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATE CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 42 Mahbubnagar K. -

CASTE SYSTEM in INDIA Iwaiter of Hibrarp & Information ^Titntt

CASTE SYSTEM IN INDIA A SELECT ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of iWaiter of Hibrarp & information ^titntt 1994-95 BY AMEENA KHATOON Roll No. 94 LSM • 09 Enroiament No. V • 6409 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Mr. Shabahat Husaln (Chairman) DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY & INFORMATION SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1995 T: 2 8 K:'^ 1996 DS2675 d^ r1^ . 0-^' =^ Uo ulna J/ f —> ^^^^^^^^K CONTENTS^, • • • Acknowledgement 1 -11 • • • • Scope and Methodology III - VI Introduction 1-ls List of Subject Heading . 7i- B$' Annotated Bibliography 87 -^^^ Author Index .zm - 243 Title Index X4^-Z^t L —i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my sincere and earnest thanks to my teacher and supervisor Mr. Shabahat Husain (Chairman), who inspite of his many pre Qoccupat ions spared his precious time to guide and inspire me at each and every step, during the course of this investigation. His deep critical understanding of the problem helped me in compiling this bibliography. I am highly indebted to eminent teacher Mr. Hasan Zamarrud, Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh for the encourage Cment that I have always received from hijft* during the period I have ben associated with the department of Library Science. I am also highly grateful to the respect teachers of my department professor, Mohammadd Sabir Husain, Ex-Chairman, S. Mustafa Zaidi, Reader, Mr. M.A.K. Khan, Ex-Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, A.M.U., Aligarh. I also want to acknowledge Messrs. Mohd Aslam, Asif Farid, Jamal Ahmad Siddiqui, who extended their 11 full Co-operation, whenever I needed. -

On Easter, Violence Resurrects in Lanka

Follow us on: facebook.com/dailypioneer RNI No.2016/1957, REGD NO. SSP/LW/NP-34/2019-21 @TheDailyPioneer instagram.com/dailypioneer/ Established 1864 OPINION 8 WORLD 12 SPORT 15 Published From GOODBYE JET SUDAN PROTEST LEADERS TO EVERTON BEAT DELHI LUCKNOW BHOPAL BHUBANESWAR RANCHI RAIPUR CHANDIGARH AIRWAYS? UNVEIL CIVILIAN RULING BODY MANCHESTER UNITED 4-0 DEHRADUN HYDERABAD VIJAYWADA Late City Vol. 155 Issue 108 LUCKNOW, MONDAY APRIL 22, 2019; PAGES 16 `3 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable FIRST FILM IS SPECIAL: AYUSHMANN} } 14 VIVACITY www.dailypioneer.com On Easter, violence resurrects in Lanka 215 killed in 8 blasts; 3 Indians, 30 other foreigners among dead PTI n NEW DELHI Modi condemns string of eight devastating Ablasts, including suicide attacks, struck churches and attack, offers help; luxury hotels frequented by for- eigners in Sri Lanka on Easter Sunday, killing 215 people, including three Indians and an Sushma in touch American, and shattering a decade of peace in the island PNS n NEW DELHI Their names are Lakshmi, nation since the end of the bru- Narayan Chandrashekhar and tal civil war with the LTTE. ondemning the “cold- Ramesh, Sushma said adding The blasts — one of the Cblooded and pre-planned details are being ascertained. deadliest attacks in the coun- barbaric acts” in Sri Lanka, Sushma tweeted, “I con- try’s history — targeted St Prime Minister Narendra veyed to the Foreign Minister Anthony’s Church in Colombo, Modi spoke to Sri Lankan of Sri Lanka that India is St Sebastian’s Church in the President Maithripala Sirisena ready to provide all humani- western coastal town of and Prime Minister Ranil tarian assistance. -

General Awareness Mega Quiz for SSC CHSL

General Awareness Mega Quiz for SSC CHSL Q1. The Battle of Plassey was fought in? (a) 1757 (b) 1782 (c) 1748 (d) 1764 Q2. The Uprising of 1857 was described as the first Indian war of Independence by ? (a) V. D. Savakar (b) B. G. Tilak (c) R. C. Mazumdar (d) S.N. Sen Q3. Who succeeded Mir Jafar ? (a) Haider Ali (b) Tipu Sultan (c) Chanda Sahib (d) Mir Qasim Q4. Which of the following battles was fought by the allied forces of Shuja-ud-Daulah, Mir Kasim and Shah Alam against Robert Clive? (a) Battle of Buxar (b) Battle of Wandiwash (c) Battle of Chelianwala (d) Battle of Tarrain Q5. The Revolt of 1857 in Awadh and Lucknow was led by (a) Wajid Ali Shah (b) Begum Hazrat Mahal (c) Asaf-ud-daula (d) Begum Zeenat Mahal Q6. The Nawab of Awadh who permanently transferred his capital from Faizabad to Lucknow was (a) Safdarjang (b) Shuja-ud-Daulah (c) Asaf-ud-daula (d) Saadat Khan 1 www.bankersadda.com | www.sscadda.com | www.careerpower.in | www.adda247.com Q7. After the initial success of the Revolt of 1857, the objective for which the leaders of the Revolt worked was (a) to restore the former glory to the Mughal empire (b) to form a Federation of Indian States under the aegis of Bhadur Shah II (c) elimination of foreign rule and return of the old order (d) each leader wanted to establish his own power in his respective region Q8. Who among the following was thrice elected president of the Indian National Congress? (a) Dadabhai Naoroji (b) Surendranath Banerji (c) Gopal Krishna Gokhle (d) Shankaran Nair Q9.