Human Automata, Identity and Creativity in George Du Maurier's Trilby and Raymond Roussel's Locus Solus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6681/theater-souvenir-programs-guide-1881-1979-256681.webp)

Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979]

Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979] RBC PN2037 .T54 1881 Choose which boxes you want to see, go to SearchWorks record, and page boxes electronically. BOX 1 1: An Illustrated Record by "The Sphere" of the Gilbert & Sullivan Operas 1939 (1939). Note: Operas: The Mikado; The Goldoliers; Iolanthe; Trial by Jury; The Pirates of Penzance; The Yeomen of the Guard; Patience; Princess Ida; Ruddigore; H.M.S. Pinafore; The Grand Duke; Utopia, Limited; The Sorcerer. 2: Glyndebourne Festival Opera (1960). Note: 26th Anniversary of the Glyndebourne Festival, operas: I Puritani; Falstaff; Der Rosenkavalier; Don Giovanni; La Cenerentola; Die Zauberflöte. 3: Parts I Have Played: Mr. Martin Harvey (1881-1909). Note: 30 Photographs and A Biographical Sketch. 4: Souvenir of The Christian King (Or Alfred of "Engle-Land"), by Wilson Barrett. Note: Photographs by W. & D. Downey. 5: Adelphi Theatre : Adelphi Theatre Souvenir of the 200th Performance of "Tina" (1916). 6: Comedy Theatre : Souvenir of "Sunday" (1904), by Thomas Raceward. 7: Daly's Theatre : The Lady of the Rose: Souvenir of Anniversary Perforamnce Feb. 21, 1923 (1923), by Frederick Lonsdale. Note: Musical theater. 8: Drury Lane Theatre : The Pageant of Drury Lane Theatre (1918), by Louis N. Parker. Note: In celebration of the 21 years of management by Arthur Collins. 9: Duke of York's Theatre : Souvenir of the 200th Performance of "The Admirable Crichton" (1902), by J.M. Barrie. Note: Oil paintings by Chas. A. Buchel, produced under the management of Charles Frohman. 10: Gaiety Theatre : The Orchid (1904), by James T. Tanner. Note: Managing Director, Mr. George Edwardes, musical comedy. -

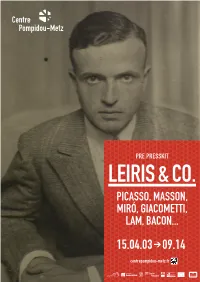

15.04.03 >09.14

PRE PRESSKIT LEIRIS & CO. PICASSO, MASSON, MIRÓ, GIACOMETTI, LAM, BACON... > 15.04.03 09.14 centrepompidou-metz.fr CONTENTS 1. EXHIBITION OVERVIEW ......................................................................... 2 2. EXHIBITION LAYOUT ............................................................................ 4 3. MICHEL LEIRIS: IMPORTANT DATES ...................................................... 9 4. PRELIMINARY LIST OF ARTISTS ........................................................... 11 5. VISUALS FOR THE PRESS ................................................................... 12 PRESS CONTACT Noémie Gotti Communications and Press Officer Tel: + 33 (0)3 87 15 39 63 Email: [email protected] Claudine Colin Communication Diane Junqua Tél : + 33 (0)1 42 72 60 01 Mél : [email protected] Cover: Francis Bacon, Portrait of Michel Leiris, 1976, Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris © The Estate of Francis Bacon / All rights reserved / ADAGP, Paris 2014 © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Bertrand Prévost LEIRIS & CO. PICASSO, MASSON, MIRÓ, GIACOMETTI, LAM, BACON... 1. EXHIBITION OVERVIEW LEIRIS & CO. PICASSO, MASSON, MIRÓ, GIACOMETTI, LAM, BACON... 03.04 > 14.09.15 GALERIE 3 At the crossroads of art, literature and ethnography, this exhibition focuses on Michel Leiris (1901-1990), a prominent intellectual figure of 20th century. Fully involved in the ideals and reflections of his era, Leiris was both a poet and an autobiographical writer, as well as a professional -

The Fin-De-Siècle Bohemian's Self-Division by John Brad Macdonald Department of English Mcgill Univers

Ambivalent Ambitions: The fin-de-siècle Bohemian’s Self-Division By John Brad MacDonald Department of English McGill University, Montreal December, 2016 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Brad MacDonald 2016 ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................... iii Abstract ...........................................................................................................................................v Résumé .......................................................................................................................................... vi Introduction ....................................................................................................................................1 I. The Rise of the Parisian Mecca: The Beginning of French Bohemia ............................14 II. From The Left Bank to Soho: The Early Days of English Bohemia ............................22 III. Rossetti, Whistler, and Wilde: The Rise of English Bohemianism .............................27 IV. Tales from the Margins: The Bohemian Text ..............................................................47 Chapter One: “Original work is never dans le movement”: The Bohemian Collective in George Moore’s A Modern Lover ...............................................................................................................59 Chapter Two: “A Place for -

Stage Hypnosis in the Shadow of Svengali: Historical Influences, Public Perceptions, and Contemporary Practices

STAGE HYPNOSIS IN THE SHADOW OF SVENGALI: HISTORICAL INFLUENCES, PUBLIC PERCEPTIONS, AND CONTEMPORARY PRACTICES Cynthia Stroud A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2013 Committee: Dr. Lesa Lockford, Advisor Dr. Richard Anderson Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Scott Magelssen Dr. Ronald E. Shields © 2013 Cynthia Stroud All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Lesa Lockford, Advisor This dissertation examines stage hypnosis as a contemporary popular entertainment form and investigates the relationship between public perceptions of stage hypnosis and the ways in which it is experienced and practiced. Heretofore, little scholarly attention has been paid to stage hypnosis as a performance phenomenon; most existing scholarship provides psychological or historical perspectives. In this investigation, I employ qualitative research methodologies including close reading, personal interviews, and participant-observation, in order to explore three questions. First, what is stage hypnosis? To answer this, I use examples from performances and from guidebooks for stage hypnotists to describe structural and performance conventions of stage hypnosis shows and to identify some similarities with shortform improvisational comedy. Second, what are some common public perceptions about stage hypnosis? To answer this, I analyze historical narratives, literary and dramatic works, film, television, and digital media. I identify nine -

Book Club Discussion Guide

Book Club Discussion Guide Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier ______________________________________________________________ About the Author Daphne du Maurier, who was born in 1907, was the second daughter of the famous actor and theatre manager-producer, Sir Gerald du Maurier, and granddaughter of George du Maurier, the much-loved Punch artist who also created the character of Svengali in the novel Trilby. After being educated at home with her sisters, and then in Paris, she began writing short stories and articles in 1928, and in 1931 her first novel, The Loving Spirit, was published. Two others followed. Her reputation was established with her frank biography of her father, Gerald: A Portrait, and her Cornish novel, Jamaica Inn. When Rebecca came out in 1938 she suddenly found herself to her great surprise, one of the most popular authors of the day. The book went into thirty-nine English impressions in the next twenty years and has been translated into more than twenty languages. There were fourteen other novels, nearly all bestsellers. These include Frenchman's Creek (1941), Hungry Hill (1943), My Cousin Rachel (1951), Mary Anne (1954), The Scapegoat (1957), The Glass-Blowers (1963), The Flight of the Falcon (1965) and The House on the Strand (1969). Besides her novels she published a number of volumes of short stories, Come Wind, Come Weather (1941), Kiss Me Again, Stranger (1952), The Breaking Point (1959), Not After Midnight (1971), Don't Look Now and Other Stories (1971), The Rendezvous and Other Stories (1980) and two plays— The Years Between (1945) and September Tide (1948). She also wrote an account of her relations in the last century, The du Mauriers, and a biography of Branwell Brontë, as well as Vanishing Cornwall, an eloquent elegy on the past of a country she loved so much. -

J.M. Barrie and the Du Mauriers

Volume 15 Number 4 Article 6 Summer 7-15-1989 J.M. Barrie and the Du Mauriers Rebecca A. Carey Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Carey, Rebecca A. (1989) "J.M. Barrie and the Du Mauriers," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 15 : No. 4 , Article 6. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol15/iss4/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Notes the influence of several members of the Du Maurier family on the writings of J.M. Barrie—particularly on Peter Pan. Additional Keywords Barrie, J.M.—Characters—Captain Hook; Barrie, J.M.—Relation to Du Maurier family; Du Maurier, George—Influence on J.M. Barrie This article is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. -

Manderley: a House of Mirrors; the Reflections of Daphne Du Maurier’S Life in Rebecca

Manderley: a House of Mirrors; the Reflections of Daphne du Maurier’s Life in Rebecca by Michele Gentile Spring 2014 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in English in cursu honorum Reviewed and approved by: Dr. Kathleen Monahan English Department Chair _______________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor Submitted to the Honors Program, Saint Peter's University 17, March 2014 Gentile2 Table of Contents Dedication…………………………………………………………………………..3 Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………...3 Abstract……………………………………………………………………………..4 Introduction………………………………………………………………………...5 Chapter I: The Unnamed Narrator………………………………………………….7 Chapter II: Rebecca……………………………………………………………….35 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………...54 Works Cited Page…………………………………………………………………55 Gentile3 Dedication: I would like to dedicate this paper to my parents, Tom and Joann Gentile, who have instilled the qualities of hard work and dedication within me throughout my entire life. Without their constant love and support, this paper would not have been possible. Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. Monahan for serving as my advisor during this experience and for introducing me to Daphne du Maurier‟s literature. Dr. Monahan, your assistance has made this process much less overwhelming and significantly more enjoyable. I would also like to thank Doris D‟Elia in assisting me with my research for this paper. Doris, your help allowed me to enjoy writing this paper, rather than fearing the research I needed to conduct. Gentile4 Abstract: Daphne du Maurier lived an unconventional life in which she rebelled against the standards society had set in place for a woman of her time. Du Maurier‟s inferiority complex, along with her incestuous feelings and bisexuality, set the stage for the characters and events in her most famous novel, Rebecca. -

Copyright by Douglas Clifton Cushing 2014

Copyright by Douglas Clifton Cushing 2014 The Thesis Committee for Douglas Clifton Cushing Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Resonances: Marcel Duchamp and the Comte de Lautréamont APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Linda Dalrymple Henderson Richard Shiff Resonances: Marcel Duchamp and the Comte de Lautréamont by Douglas Clifton Cushing, B.F.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin August 2014 Dedication In memory of Roger Cushing Jr., Madeline Cushing and Mary Lou Cavicchi, whose love, support, generosity, and encouragement led me to this place. Acknowledgements For her loving support, inspiration, and the endless conversations on the subject of Duchamp and Lautréamont that she endured, I would first like to thank my fiancée, Nicole Maloof. I would also like to thank my mother, Christine Favaloro, her husband, Joe Favaloro, and my stepfather, Leslie Cavicchi, for their confidence in me. To my advisor, Linda Dalrymple Henderson, I owe an immeasurable wealth of gratitude. Her encouragement, support, patience, and direction have been invaluable, and as a mentor she has been extraordinary. Moreover, it was in her seminar that this project began. I also offer my thanks to Richard Shiff and the other members of my thesis colloquium committee, John R. Clarke, Louis Waldman, and Alexandra Wettlaufer, for their suggestions and criticism. Thanks to Claire Howard for her additions to the research underlying this thesis, and to Willard Bohn for his help with the question of Apollinaire’s knowledge of Lautréamont. -

Palermo Deathtrip

188 Spirits of Place Palermo Deathtrip Iain Sinclair Dead already and dead again. – Jack Kerouac he shadows of war planes printing across bare, bone- dry fi elds. Another invasion fl eet in a cloudless sky-ocean. Sandcastles and defensive mounds fl oat- T ing free like barrage balloons. From Africa and the scatt ered islands, they fi nd their justifi cation in the aerial devas- tation that travelled the other way, south, with iron crosses on the wings. A golden gerfalcon on a Norman batt le standard. Flicker- ing newsreels swamped by martial music and the choke of strident propagandist voices. In the year of my birth. In the safety of windowless studios. Fire-storms against Templars and populace in their cool burrows. In round-bellied grain cellars. And catacombs. Sleeping on platforms of sleepers, the folded dead hidden from sunlight. A harvest of Su- perfortress bombs for the port, the occupied city. Icarus refl exes in 190 Spirits of Place Palermo Deathtrip 191 a leather helmet. From this lung-pinching height the landscape is A folly. A strong woman of the north in snowy wrap. Acolytes a map of mortality. Gold pillars and tributes to a water clock in the in white suits and dark glasses. Made darker with aircraft paint. interior dazzle of the Palatine Chapel. Blinding them from the forbidden sight as a Homeric sun rises, in cloud-piercing searchlight beams, over the blue mountains. Across g the harbour. As the fishing boats putputput out to sea. Hefty handmaidens attend, catching the towelling wrap as the presence 1985. -

Richard Kostelanetz

Other Works by Richard Kostelanetz Fifty Untitled Constructivst Fictions (1991); Constructs Five (1991); Books Authored Flipping (1991); Constructs Six (1991); Two Intervals (1991); Parallel Intervals (1991) The Theatre of Mixed Means (1968); Master Minds (1969); Visual Lan guage (1970); In the Beginning (1971); The End of Intelligent Writing (1974); I Articulations/Short Fictions (1974); Recyclings, Volume One (1974); Openings & Closings (1975); Portraits from Memory (1975); Audiotapes Constructs (1975); Numbers: Poems & Stories (1975); Modulations/ Extrapolate/Come Here (1975); Illuminations (1977); One Night Stood Experimental Prose (1976); Openings & Closings (1976); Foreshortenings (1977); Word sand (1978); ConstructsTwo (1978); “The End” Appendix/ & Other Stories (1977); Praying to the Lord (1977, 1981); Asdescent/ “The End” Essentials (1979); Twenties in the Sixties (1979); And So Forth Anacatabasis (1978); Invocations (1981); Seductions (1981); The Gos (1979); More Short Fictions (1980); Metamorphosis in the Arts (1980); pels/Die Evangelien (1982); Relationships (1983); The Eight Nights of The Old Poetries and the New (19 81); Reincarnations (1981); Autobiogra Hanukah (1983);Two German Horspiel (1983);New York City (1984); phies (1981); Arenas/Fields/Pitches/Turfs (1982); Epiphanies (1983); ASpecial Time (1985); Le Bateau Ivre/The Drunken Boat (1986); Resume American Imaginations (1983); Recyclings (1984); Autobiographicn New (1988); Onomatopoeia (1988); Carnival of the Animals (1988); Ameri York Berlin (1986); The Old Fictions -

Re-Reading Villainy and Gender in Daphne Du Maurier's Rebecca

PATRIARCHAL HAUNTINGS: RE-READING VILLAINY AND GENDER IN DAPHNE DU MAURIER’S REBECCA Auba Llompart Pons Supervised by Dr Sara Martín Alegre Departament de Filología Anglesa i de Germanística MA in Advanced English Studies: Literature and Culture July 2008 PATRIARCHAL HAUNTINGS: RE-READING VILLAINY AND GENDER IN DAPHNE DU MAURIER’S REBECCA TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction (p. 1) 2. Revisiting Bluebeard’s Castle: Maxim de Winter’s Double Murder and du Maurier’s Re-working of the Femicidal Villain (p. 7) 2.1. The Identity Crisis of Bluebeard’s Second Wife: Psychological Destruction and Alienation in Manderley (p. 10) 2.2. Unlocking the Door of the Forbidden Cabin: Male Hysteria, Femicide and Maxim de Winter’s Fear of the Feminization of the Estate (p. 15) 3. From Bluebeard to ‘Gentleman Unknown’: The Victimization of Maxim de Winter and the Villainy of Patriarchy (p. 25) 3.1. “We Are All Children in Some Ways”: Vatersehnsucht , Brotherhood and the Crisis of Masculine Identity (p. 28) 3.2. “Last Night I Dreamt I Went to Manderley Again”: The Patriarchal System as the Ultimate Haunting Presence in Rebecca (p. 36) 4. Conclusions (p. 43) 5. Bibliography and Filmography (p. 45) 1. INTRODUCTION English writer Daphne du Maurier (1907 – 1989), author of novels, plays and short stories, has been described as “an entertainer born of entertainers” 1 (Stockwell, 1955: 214), who appeals to “the average reader looking for a temporary escape from the perils of this mortal life” (Stockwell, 1955: 221). Her best-known novel, Rebecca , first published in 1938, and adapted many times for the theatre, the cinema and the television 2, has proved to be “an enduring classic of popular fiction” (Watson, 2005: 13). -

Series 1. Actors, Actresses, Entertainers

Theatre Collection Illustrations / chiefly collected by Miss Angel Symon MSS 792 T37428 Series 1 A-D Yellow cells = Oversize, stored separately Grey = Missing? 1A. Actors and Actresses – individuals No. Details Year Notes 1a Abington, Mrs Frances 1815 Engraving 1b Abington, Mrs. As “Charlotte” in “The Hypocrite” 1786 Engraving 1c Abington, Mrs. as “Lady Polly?” [1812] Engraving 1d Abington, Mrs. as “Olivia” 1779 Engraving 2a Alexander, George Photograph 2b Alexander, George as “Orlando” 1896 Photo 3a Allan, Maud 2 postcards from photographs 1-2 4 Anderson, Miss Mary as “Hermione” Photograph 5 Anthony, Miss Hilda Postcard from photo, Hand-coloured. Addressed to Lenore Symon from Aube (?) Amos. Dated 11 January 1907 6 Asche, Oscar as “Petrichio” Photograph (Edinburgh Folio) 7 Atkins, Mrs Elizabeth as “Selima” in “Selima & Azor” Print 8 Baddely [Baddeley]. Mr Robert. Engraving 9 Baird, Dorothea as “Rosalind” Photograph (Edinburgh Folio) 10 Bandmann, Daniel E Photograph 11 Bandmann, Mrs Millicent Photograph 12a Bannister Junior, Mr John. as “Ben the Sailor” Engraving 12b Bannister, Mr. - as “Dick” in “Apprentice” Print 12c Bannister, Mr. John – Comedian 1795 Engraving 13 Baratti Photo 14 Barry, Spranger (1719-1777) as “Macbeth” Postcard of a Mezzotint by J. Gwinn (Harry Beard Collection) 15 Beattie [Beatty], May? Photo 16 Beattie [Beatty], Miss May 1906 Hand-coloured postcard from a photograph. Addressed to Miss Symon, from L. S. [Lenore Symon?] 17 Beaumont [Armes] Photograph 18 missing 19 Bellamy, Mrs. George Anne Engraving 20 Bellew, Kyrle as “Romeo” [1896] Photograph 21a Bennett, Mr George as “Lucius Cataline” Engraving 21b Bennet, Mr George as “Hubert” in “King John” Hand-coloured engraving 21c Bennett, Mr George.