Wyndham Lewis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

15.04.03 >09.14

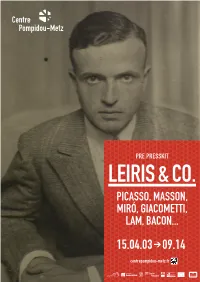

PRE PRESSKIT LEIRIS & CO. PICASSO, MASSON, MIRÓ, GIACOMETTI, LAM, BACON... > 15.04.03 09.14 centrepompidou-metz.fr CONTENTS 1. EXHIBITION OVERVIEW ......................................................................... 2 2. EXHIBITION LAYOUT ............................................................................ 4 3. MICHEL LEIRIS: IMPORTANT DATES ...................................................... 9 4. PRELIMINARY LIST OF ARTISTS ........................................................... 11 5. VISUALS FOR THE PRESS ................................................................... 12 PRESS CONTACT Noémie Gotti Communications and Press Officer Tel: + 33 (0)3 87 15 39 63 Email: [email protected] Claudine Colin Communication Diane Junqua Tél : + 33 (0)1 42 72 60 01 Mél : [email protected] Cover: Francis Bacon, Portrait of Michel Leiris, 1976, Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris © The Estate of Francis Bacon / All rights reserved / ADAGP, Paris 2014 © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Bertrand Prévost LEIRIS & CO. PICASSO, MASSON, MIRÓ, GIACOMETTI, LAM, BACON... 1. EXHIBITION OVERVIEW LEIRIS & CO. PICASSO, MASSON, MIRÓ, GIACOMETTI, LAM, BACON... 03.04 > 14.09.15 GALERIE 3 At the crossroads of art, literature and ethnography, this exhibition focuses on Michel Leiris (1901-1990), a prominent intellectual figure of 20th century. Fully involved in the ideals and reflections of his era, Leiris was both a poet and an autobiographical writer, as well as a professional -

Copyright by Douglas Clifton Cushing 2014

Copyright by Douglas Clifton Cushing 2014 The Thesis Committee for Douglas Clifton Cushing Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Resonances: Marcel Duchamp and the Comte de Lautréamont APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Linda Dalrymple Henderson Richard Shiff Resonances: Marcel Duchamp and the Comte de Lautréamont by Douglas Clifton Cushing, B.F.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin August 2014 Dedication In memory of Roger Cushing Jr., Madeline Cushing and Mary Lou Cavicchi, whose love, support, generosity, and encouragement led me to this place. Acknowledgements For her loving support, inspiration, and the endless conversations on the subject of Duchamp and Lautréamont that she endured, I would first like to thank my fiancée, Nicole Maloof. I would also like to thank my mother, Christine Favaloro, her husband, Joe Favaloro, and my stepfather, Leslie Cavicchi, for their confidence in me. To my advisor, Linda Dalrymple Henderson, I owe an immeasurable wealth of gratitude. Her encouragement, support, patience, and direction have been invaluable, and as a mentor she has been extraordinary. Moreover, it was in her seminar that this project began. I also offer my thanks to Richard Shiff and the other members of my thesis colloquium committee, John R. Clarke, Louis Waldman, and Alexandra Wettlaufer, for their suggestions and criticism. Thanks to Claire Howard for her additions to the research underlying this thesis, and to Willard Bohn for his help with the question of Apollinaire’s knowledge of Lautréamont. -

Palermo Deathtrip

188 Spirits of Place Palermo Deathtrip Iain Sinclair Dead already and dead again. – Jack Kerouac he shadows of war planes printing across bare, bone- dry fi elds. Another invasion fl eet in a cloudless sky-ocean. Sandcastles and defensive mounds fl oat- T ing free like barrage balloons. From Africa and the scatt ered islands, they fi nd their justifi cation in the aerial devas- tation that travelled the other way, south, with iron crosses on the wings. A golden gerfalcon on a Norman batt le standard. Flicker- ing newsreels swamped by martial music and the choke of strident propagandist voices. In the year of my birth. In the safety of windowless studios. Fire-storms against Templars and populace in their cool burrows. In round-bellied grain cellars. And catacombs. Sleeping on platforms of sleepers, the folded dead hidden from sunlight. A harvest of Su- perfortress bombs for the port, the occupied city. Icarus refl exes in 190 Spirits of Place Palermo Deathtrip 191 a leather helmet. From this lung-pinching height the landscape is A folly. A strong woman of the north in snowy wrap. Acolytes a map of mortality. Gold pillars and tributes to a water clock in the in white suits and dark glasses. Made darker with aircraft paint. interior dazzle of the Palatine Chapel. Blinding them from the forbidden sight as a Homeric sun rises, in cloud-piercing searchlight beams, over the blue mountains. Across g the harbour. As the fishing boats putputput out to sea. Hefty handmaidens attend, catching the towelling wrap as the presence 1985. -

Richard Kostelanetz

Other Works by Richard Kostelanetz Fifty Untitled Constructivst Fictions (1991); Constructs Five (1991); Books Authored Flipping (1991); Constructs Six (1991); Two Intervals (1991); Parallel Intervals (1991) The Theatre of Mixed Means (1968); Master Minds (1969); Visual Lan guage (1970); In the Beginning (1971); The End of Intelligent Writing (1974); I Articulations/Short Fictions (1974); Recyclings, Volume One (1974); Openings & Closings (1975); Portraits from Memory (1975); Audiotapes Constructs (1975); Numbers: Poems & Stories (1975); Modulations/ Extrapolate/Come Here (1975); Illuminations (1977); One Night Stood Experimental Prose (1976); Openings & Closings (1976); Foreshortenings (1977); Word sand (1978); ConstructsTwo (1978); “The End” Appendix/ & Other Stories (1977); Praying to the Lord (1977, 1981); Asdescent/ “The End” Essentials (1979); Twenties in the Sixties (1979); And So Forth Anacatabasis (1978); Invocations (1981); Seductions (1981); The Gos (1979); More Short Fictions (1980); Metamorphosis in the Arts (1980); pels/Die Evangelien (1982); Relationships (1983); The Eight Nights of The Old Poetries and the New (19 81); Reincarnations (1981); Autobiogra Hanukah (1983);Two German Horspiel (1983);New York City (1984); phies (1981); Arenas/Fields/Pitches/Turfs (1982); Epiphanies (1983); ASpecial Time (1985); Le Bateau Ivre/The Drunken Boat (1986); Resume American Imaginations (1983); Recyclings (1984); Autobiographicn New (1988); Onomatopoeia (1988); Carnival of the Animals (1988); Ameri York Berlin (1986); The Old Fictions -

Raymond Roussel En Iberia

31/3/2021 Raymond Roussel en Iberia. La traducción de sus métodos de escritura RAYMOND ROUSSEL EN IBERIA. LA TRADUCCIÓN DE SUS MÉTODOS DE ESCRITURA Hermes Salceda Departamento de Filología inglesa, francesa y alemana Universidad de Vigo 2020 Recibido: 20 enero 2020 Aceptado: 24 abril 2020 Introducción Ya nadie duda que Raymond Roussel (1877-1933) es uno de los escritores franceses más originales e innovadores de principios del siglo XX, sin embargo, el prestigio que se asocia a su figura no va acompañado de una difusión en otras lenguas. Roussel es un caso de desajuste extremo entre el capital simbólico que se le atribuye (la influencia que se le reconoce en las letras y en las artes) y la limitada circulación de su obra fuera de los distinguidos círculos de iniciados. Estamos ante el más ilustre desconocido de las letras francesas del siglo XX. En la escasa difusión de sus libros han influido factores variados, entre ellos su difícil penetración en el espacio académico y, sin duda, los complejos problemas de traducción que presentan sus textos (compuestos la mayoría, con su famoso Procedimiento basado en asociaciones hominímicas y homofónicas). Esto explica, por ejemplo, que no se haya traducido a ninguna de las lenguas del mundo, el más conocido de sus libros, su testamento literario Como escribí algunos libros míos (1935) y que haya tan pocas versiones de su obra más compleja, Nouvelles Impressions d’Afrique (1932). Con todo, las dificultades específicas de su escritura (su modo radical de plantear «ecuaciones lingüísticas» como principal fuente de invención ficcional) han interpelado a excelentes traductores en las distintas lenguas de la península ibérica. -

Roussel Brisset Duchamp

ROUSSEL BRISSET DUCHAMP Three Inventors: Brisset, Roussel, Duchamp 3 Three Inventors: Jean-Pierre Brisset, Raymond Roussel, Marcel Duchamp Maximilian Gilleßen Translated by Raphael Koenig Jean-Pierre Brisset, Raymond Roussel, Marcel Duchamp: three men whose names are inextricably linked by their respective intellectual trajectories, creative processes, and reception histories. Similarities between them abound, and can also be perceived in minute biographical details, accidents, and coincidences. Their well-known penchant for treating aesthetic issues as issues of methodology provided all three of them with the impetus to devote themselves to technical innovations, which is maybe a lesser known aspect of their respective works. Brisset, Roussel, and Duchamp all took out patents at the French Office national de la propriété industrielle: another feather in their cap, so to speak, in addition to their aesthetic achievements. While these technical inventions might seem far removed from their official, canonical bodies of work, it is precisely this distance that could allow us to shed new light on the leitmotivs and obsessions of their creators; they are the flip side of their linguistic, literary, and artistic endeavors, constituting their obscure but highly significant supplement. 4 Three Inventors: Brisset, Roussel, Duchamp Three Inventors: Brisset, Roussel, Duchamp 5 Brisset, or the Repetition of Origins desire, or fear, allow Brisset to retrace the history of the Jean-Pierre Brisset, who would have featured prominently slow transformation of the primitive frogs into modern alongside with Roussel in Duchamp’s “ideal library,”1 is best humans. For instance, he singles out the phonetic known as an author of linguistic and prophetic tractates, resemblance between the German word die Zähne (the in which he attempted to prove that humans had evolved teeth) and the French numeral dizaine (ten) as a means from frogs on the basis of a phonetic analysis of the French of investigating the early origins of our dentition. -

A Film by Peter Volkart

HOMMAGE À RAYMOND ROUSSEL A FILM BY PETER VOLKART with_PAUL AVONDET SANDRA KÜNZI narrator_VOLKER RISCH BODO KRUMWIEDE cinematography_HANSUELI SCHENKEL compositing_VOLKART&VOLKART PAUL AVONDET sound design_VOCO FAUXPAS sound mix_CHRISTIAN BEUSCH editing_HARALD & HERBERT producer_FRANZISKA RECK © 2005 RECK FILMPRODUKTION Unterstützt durch: Bundesamt für Kultur (EDI) Stadt und Kanton Zürich, Migros Kulturprozent re:view Familien-Vontobel-Stiftung, Dr. Adolf Streuli-Stiftung Ernst und Olga Gubler-Hablützel Stiftung, Volkart Stiftung Stiftung Birsig für Kunst und Kultur Friedrich-Jezler-Stiftung HOMMAGE À RAYMOND ROUSSEL A FILM BY PETER VOLKART Fiction, 35mm, Deutsche Originalversion (s.t. français, english subtitles), 15 min, Switzerland 2005 He was in the headlines for a brief period in the late 1920s: Igor Leschenko, the young physicist from Hermannstadt, whose bizarre experiments cast doubt upon the law of gravity. The debacle at the pataphysicist convention leads to a secret expedition to the point of zero gravity. Rare film documents of a hazardous journey beyond Zentropa through the Karfunkel archipelago. Will Leschenko ever find the Nanopol island? Igor Leschenko a brièvement fait les gros titres à la fin des années 20. Le jeune physicien d’Hermannstadt qui avait ébranlé la loi de la gravité avec ses expériences bizarres, c’est lui. La débâcle au congrès des pataphysiciens fut suivie d’une expédition secrète jusqu’au point d’anti-gravité. Des films documentaires rares retracent un voyage au-delà de Zentropa à travers l’archipel menaçant de Karfunkel. Igor Leschenko découvrira-t-il l’île Nanopol? Ende der 20er Jahre war er kurz in den Schlagzeilen: Igor Leschenko, der junge Physiker aus Hermannstadt, der mit seinen bizarren Experimenten das Gesetz der Schwerkraft ins Wanken bringt. -

Surrealism Su Alism

7 × 10 SPINE: 0.8125 FLAPS: 0 Art history / Modernism SU n SURREALISM AT PLAY Susan Laxton writes a new history of surrealism in which she traces the central- ity of play to the movement and its ongoing legacy. For surrealist artists, play RRE took a consistent role in their aesthetic as they worked in, with, and against a post-WWI world increasingly dominated by technology and functionalism. Whether through exquisite corpse drawings, Man Ray’s rayographs, or Joan I Miró’s visual puns, surrealists became adept at developing techniques and pro- cesses designed to guarantee aleatory outcomes. In embracing chance as the means to produce unforeseeable ends, they shi ed emphasis from nal product to process, challenging the disciplinary structures of industrial modernism. As Laxton demonstrates, play became a primary method through which surrealism ALISM refashioned artistic practice, everyday experience, and the nature of subjectivity. “ is long-awaited and important book situates surrealism in relation to Walter Benjamin’s idea that, with the withering of aura, there is an expansion of room for play. Susan Laxton shows how surrealist activities unleashed the revolution- ary power of playfulness on modernity’s overvaluation of rationality and utility. In doing so, they uncovered technology’s ludic potential. is approach casts new light on the work of Man Ray, Joan Miró, and Alberto Giacometti, among AT PLAY AT others, in ways that also illuminate the work of postwar artists.” MARGARET IVERSEN, author of Photography, Trace, and Trauma “ André Breton began the Manifesto of Surrealism by remembering childhood and play: ‘ e woods are white or black, one will never sleep!’ Susan Laxton’s Surrealism at Play recaptures the sense that surrealism should be approached as an activity, and one as open and as transgressive as this. -

Locus Solus Impressions of Raymond Roussel Reading Roussel Was Also

Locus Solus 26 October 2011 - 27 February 2012 Locus Solus Impressions of Raymond Roussel Impressions of Raymond Roussel Often described by his contemporaries as a haughty Even if he was only to become aware of the fact late in his life, Reading Roussel was also fundamental to the creation of dandy, he did indeed spend most of his life retired during his lifetime Roussel attracted a great deal of enthusiasm Salvador Dali’s paranoiac-critical theory during the 1930s. To from society. Though his “life was constructed like among a generation of artists and poets. Marcel Duchamp, Roussel’s doubling of words, Dali answered with a doubling his books”, in the words of the psychiatrist Pierre who attended with Guillaume Apollinaire and Francis Picabia, of images. The crystal transparency of Roussel’s texts, in Janet, he was in reality an enthusiastic character, one of the performances of Impressions of Africa in 1912 was particular his poem The View, provided Dali with a model for whose worship of genius came firstly from his to recall it as a primary influence on his Large Glass. The his “rigurosa lógica de la Fantasía”. Confirming the necessary loyal attachment to his childhood memories and photographic precision of Roussel’s laconic writing, his taste exactitude of the imagination, it gane rise to visions that reading, and subsequently from his devotion to for technical and scientific innovations, as well as the absence materialise subconscious desires as closely as possible. those whom he considered to be great minds: Jules of any psychological depth in his characters, who seem simply Verne and Pierre Loti with their real or imaginary puppets lacking in depth, make Roussel one of the sources of the In an article published in the review Le Surréalisme au service travels, the astronomer Camille Flammarion or the “bachelor machines”, as the writer Michel Carrouges pointed de la Révolution, in 1933, a few months before Roussel’s death, poet Victor Hugo. -

Scenodynamic Architecture and the Avant Garde Sozita Goudouna

Solitary Place: Scenodynamic Architecture and The Avant Garde Sozita Goudouna* The clarity and transparency of Roussel’s works, exclude the existence of other worlds behind things and yet we discover that we can't get out of this world. Everything is at a standstill, everything is always happening all over again. In 1914, Raymond Roussel (1877-1933), one of the ancestors of experimental writing and forerunners of avant-garde art practices, commissioned Pierre Frondaie a popular pulp fiction writer, to turn his novel Locus Solus (‘Solitary or Unique Place’) into a play. The production, however, was a complete failure. Roussel and his strangely titled work became the butt of jokes overnight, and everyone waited with impatient malice for the next play. The paper examines the three modular stages (and spaces/stages- locations/loci) of a three year project based on Roussel’s Locus Solus so as to discuss a wide range of possibilities of re-visioning and re-making the context in which Locus Solus was framed, misread, misunderstood and mis- fitted during the epoch it was written. The paper presents theoretical and artistic perspectives that reflect on the boundary between theatrical and visual practices, and on the contemporary focus that accompanies the relation between personhood and objecthood, in the theatre, by providing an overview of the ways in which the collaborating artists draw on ‘scenodynamic architecture’ and on scientific and technological developments to explore public interfaces between art and science, between public and private (solitary) space, new forms of creative expression and to unfold the wide range of disciplines, genres, theoretical, and artistic positions that comprise the relationships between spectator, artist, architect/scientist and director/curator. -

Human Automata, Identity and Creativity in George Du Maurier's Trilby and Raymond Roussel's Locus Solus

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-15-2012 12:00 AM Human Automata, Identity and Creativity in George Du Maurier's Trilby and Raymond Roussel's Locus Solus Adrienne M. Orr The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Christopher Keep The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Adrienne M. Orr 2012 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, French and Francophone Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Orr, Adrienne M., "Human Automata, Identity and Creativity in George Du Maurier's Trilby and Raymond Roussel's Locus Solus" (2012). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 703. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/703 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HUMAN AUTOMATA, IDENTITY AND CREATIVITY IN GEORGE DU MAURIER’S TRILBY AND RAYMOND ROUSSEL’S LOCUS SOLUS (Spine title: Human Automata, Identity and Creativity in Trilby and Locus Solus ) (Thesis format: Monograph) by Adrienne Orr Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Adrienne Orr 2012 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners ______________________________ ______________________________ Dr. -

Jules Verne and the French Literary Canon

DePauw University Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University Modern Languages Faculty publications Modern Languages 2000 Jules Verne and the French Literary Canon Arthur B. Evans DePauw University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.depauw.edu/mlang_facpubs Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons Recommended Citation Arthur B. Evans. "Jules Verne and the French Literary Canon." In Jules Verne: Narratives of Modernity, edited by Edmund Smyth, 11-39. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2000. Copyright Liverpool University Press. Available at: http://scholarship.depauw.edu/mlang_facpubs/58/ The original article may be obtained here: http://liverpool.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.5949/liverpool/ 9780853236948.001.0001/upso-9780853236948-chapter-2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Modern Languages at Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern Languages Faculty publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 11 [Appeared in Jules Verne: Narratives of Modernity. Edited by Edmund Smyth. Liverpool UP, 2000, pp. 11-39.] Arthur B. Evans Jules Verne and the French Literary Canon 1863-1905 The curious contradiction of Jules Verne’s popular success and literary rebuff in France began during his own lifetime—from the moment his first Voyages extraordinaires appeared in the French marketplace in 1863-65 until his death in 1905. From the publication of his earliest novels—Cinq semaines en ballon (1863), Voyage au centre de la Terre (1864), and De la Terre à la Lune (1865)—the sales of Verne’s works were astonishing, earning him the recognition he sought as an up-and-coming novelist.