Federalism in Nepal: a Tharu Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nepal Side, We Must Mention Prof

The Journal of Newar Studies Swayambhv, Ifliihichaitya Number - 2 NS 1119 (TheJournal Of Newar Studies) NUmkL2 U19fi99&99 It has ken a great pleasure bringing out the second issue of EdltLlo the journal d Newar Studies lijiiiina'. We would like to thank Daya R Sha a Gauriehankar Marw&~r Ph.D all the members an bers for their encouraging comments and financial support. ivc csp~iilly:-l*-. urank Prof. Uma Shrestha, Western Prof.- Todd ttwria Oregon Univers~ty,who gave life to this journd while it was still in its embryonic stage. From the Nepal side, we must mention Prof. Tej Shta Sudip Sbakya Ratna Kanskar, Mr. Ram Shakya and Mr. Labha Ram Tuladhar who helped us in so many ways. Due to our wish to publish the first issue of the journal on the Sd Fl~ternatioaalNepal Rh&a levi occasion of New Nepal Samht Year day {Mhapujii), we mhed at the (INBSS) Pdand. Orcgon USA last minute and spent less time in careful editing. Our computer Nepfh %P Puch3h Amaica Orcgon Branch software caused us muble in converting the files fm various subrmttd formats into a unified format. We learn while we work. Constructive are welcome we try Daya R Shakya comments and will to incorporate - suggestions as much as we can. Atedew We have received an enormous st mount of comments, Uma Shrcdha P$.D.Gaurisbankar Manandhar PIID .-m -C-.. Lhwakar Mabajan, Jagadish B Mathema suggestions, appreciations and so forth, (pia IcleI to page 94) Puma Babndur Ranjht including some ~riousconcern abut whether or not this journal Rt&ld Rqmmtatieca should include languages other than English. -

Policy Note for the Federalism Transition in Nepal

Policy Note for the Federalism Transition in Nepal AUGUST 2019 Empowered lives. Resilient nations. Abbreviations and Acronyms CIP Capital Investment Plan FCNA Federalism Capacity Needs Assessment HEZ Himalayan Ecological Zone GDP Gross Domestic Product GRB Gender Responsive Budgeting GESI Gender Equality and Social Inclusion GoN Government of Nepal IPC Inter-Provincial Council LDTA Local Development Training Academy LGCDP Local Governance and Community Development Program LMBIS Line Ministry Budget Information System MOFAGA Ministry of Federal Affairs and General Administration NPSAS National Public Sector Accounting Standards NNRFC National Natural Resource and Fiscal Commission O&M Organization and Management OPMCM Office of the Prime Minister and Council of Ministers PEFA Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability PFM Public Financial Management PIFIP Physical Infrastructure and Facility Improvement Plan PPSC Provincial Public Service Commission PLGs Provincial and Local Governments SUTRA Sub-National Treasury Regulatory Application TEZ Terai Ecological Zone i Table of Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms ........................................................................................................................ i Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................................... ii Foreword .................................................................................................................................................... -

Federalism Is Debated in Nepal More As an ‘Ism’ Than a System

The FEDERALISM Debate in Nepal Post Peace Agreement Constitution Making in Nepal Volume II Post Peace Agreement Constitution Making in Nepal Volume II The FEDERALISM Debate in Nepal Edited by Budhi Karki Rohan Edrisinha Published by United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Support to Participatory Constitution Building in Nepal (SPCBN) 2014 United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Support to Participatory Constitution Building in Nepal (SPCBN) UNDP is the UN’s global development network, advocating for change and connecting countries to knowledge, experience and resources to help people build a better life. United Nations Development Programme UN House, Pulchowk, GPO Box: 107 Kathmandu, Nepal Phone: +977 1 5523200 Fax: +977 1 5523991, 5523986 ISBN : 978 9937 8942 1 0 © UNDP, Nepal 2014 Book Cover: The painting on the cover page art is taken from ‘A Federal Life’, a joint publication of UNDP/ SPCBN and Kathmandu University, School of Art. The publication was the culmination of an initiative in which 22 artists came together for a workshop on the concept of and debate on federalism in Nepal and then were invited to depict their perspective on the subject through art. The painting on the cover art titled ‘’Emblem” is created by Supriya Manandhar. DISCLAIMER: The views expressed in the book are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of UNDP/ SPCBN. PREFACE A new Constitution for a new Nepal drafted and adopted by an elected and inclusive Constituent Assembly (CA) is a key element of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) of November 2006 that ended a decade long Maoist insurgency. -

Nepal's Constitution (Ii): the Expanding

NEPAL’S CONSTITUTION (II): THE EXPANDING POLITICAL MATRIX Asia Report N°234 – 27 August 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. THE REVOLUTIONARY SPLIT ................................................................................... 3 A. GROWING APART ......................................................................................................................... 5 B. THE END OF THE MAOIST ARMY .................................................................................................. 7 C. THE NEW MAOIST PARTY ............................................................................................................ 8 1. Short-term strategy ....................................................................................................................... 8 2. Organisation and strength .......................................................................................................... 10 3. The new party’s players ............................................................................................................. 11 D. REBUILDING THE ESTABLISHMENT PARTY ................................................................................. 12 1. Strategy and organisation .......................................................................................................... -

![New Accessions, July– September 2019) Compiled by Karl-Heinz Krämer [Excerpt from the Complete Literature Index of Nepal Research]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6544/new-accessions-july-september-2019-compiled-by-karl-heinz-kr%C3%A4mer-excerpt-from-the-complete-literature-index-of-nepal-research-816544.webp)

New Accessions, July– September 2019) Compiled by Karl-Heinz Krämer [Excerpt from the Complete Literature Index of Nepal Research]

ACADEMIC WORKS AND SELECTED PRESS ARTICLES (New accessions, July– September 2019) Compiled by Karl-Heinz Krämer [Excerpt from the complete literature index of Nepal Research] Acharya, Vagyadi. 2019. Decline of constitutionalism: Ensure separation of powers. The Himalayan Times, 2 July 2019 Adhikari, Ajaya Kusum. 2019. Digitalizing farming: Digitalizing farming process by providing farmers access to the internet can help solve most of the problems facing Nepali farmers, including improving competitiveness in farming. República, 25 July 2019 Adhikari, Ajaya Kusum. 2019. State of real estate: How is it possible that land prices in Nepali cities with poor infrastructure are close to land prices in London, New York, Tokyo and Shanghai?. República, 11 September 2019 Adhikari, Bipin. 2019. Building District Coordination Committees. Annapurna Express, 16 August 2019 Adhikari, Chandra Shekhar. 2019. ‘Honorary’ foreign policy: NRNs are honorary consuls in Australia, Canada, Portugal, the US and Germany. They have no responsibility besides catering to high level Nepali dignitaries when they visit these countries. Annapurna Express, 12 July 2019 Adhikari, Devendra. 2019. Solar energy promotion: Learn from Bangladesh. The Himalayan Times, 5 September 2019 Adhikari, Jagannath. 2019. Reviving Nepal’s rural economy: Nepal can take cues from post-second world war Tuscany and promote agro-tourism. The Kathmandu Post, 20 August 2019 Adhikari, Kriti. 2019. Children of slain journalists find succor: But for how long?. Annapurna Express, 12 July 2019 Adhikari, Pradip. 2019. Reimagining education: Students need to be trained to challenge conventional wisdom and to create new ideas. These skills can be garnered if students are allowed free thought and taught questioning skills. -

NEWAR ARCHITECTURE the Typology of the Malla Period Monuments of the Kathmandu Valley

BBarbaraarbara Gmińska-NowakGmińska-Nowak Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń Polish Institute of World Art Studies NEWAR ARCHITECTURE The typology of the Malla period monuments of the Kathmandu Valley INTRODUCTION: NEPAL AND THE KATHMANDU VALLEY epal is a country with an old culture steeped in deeply ingrained tradi- tion. Political, trade and dynastic relations with both neighbours – NIndia and Tibet, have been intense for hundreds of years. The most important of the smaller states existing in the current territorial borders of Nepal is that of the Kathmandu Valley. This valley has been one of the most important points on the main trade route between India and Tibet. Until the late 18t century, the wealth of the Kathmandu Valley reflected in the golden roofs of numerous temples and the monastic structures adorned by artistic bronze and stone sculptures, woodcarving and paintings was mainly gained from commerce. Being the point of intersection of significant trans-Himalaya trade routes, the Kathmandu Valley was a centre for cultural exchange and a place often frequented by Hindu and Buddhist teachers, scientists, poets, architects and sculptors.1) The Kathmandu Valley with its main cities of Kathmandu, Patan and Bhak- tapur is situated in the northeast of Nepal at an average height of 1350 metres above sea level. Today it is still the administrative, cultural and historical centre of Nepal. South of the valley lies a mountain range of moderate height whereas the lofty peaks of the Himalayas are visible in the North. 1) Dębicki (1981: 11 – 14). 10 Barbara Gmińska-Nowak The main group of inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley are the Newars, an ancient and high organised ethnic group very conscious of its identity. -

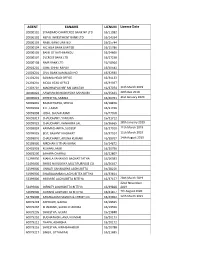

List of Active Agents

AGENT EANAME LICNUM License Date 20000101 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK NP LTD 16/11082 20000102 NEPAL INVESTMENT BANK LTD 16/14334 20000103 NABIL BANK LIMITED 16/15744 20000104 NIC ASIA BANK LIMITED 16/15786 20000105 BANK OF KATHMANDU 16/24666 20000107 EVEREST BANK LTD. 16/27238 20000108 NMB BANK LTD 16/18964 20901201 GIME CHHETRAPATI 16/30543 21001201 CIVIL BANK KAMALADI HO 16/32930 21101201 SANIMA HEAD OFFICE 16/34133 21201201 MEGA HEAD OFFICE 16/34037 21301201 MACHHAPUCHRE BALUWATAR 16/37074 11th March 2019 40000022 AAWHAN BAHUDAYSIYA SAHAKARI 16/35623 20th Dec 2019 40000023 SHRESTHA, SABINA 16/40761 31st January 2020 50099001 BAJRACHARYA, SHOVA 16/18876 50099003 K.C., LAXMI 16/21496 50099008 JOSHI, SHUVALAXMI 16/27058 50099017 CHAUDHARY, YAMUNA 16/31712 50099023 CHAUDHARY, KANHAIYA LAL 16/36665 28th January 2019 50099024 KARMACHARYA, SUDEEP 16/37010 11th March 2019 50099025 BIST, BASANTI KADAYAT 16/37014 11th March 2019 50099026 CHAUDHARY, ARUNA KUMARI 16/38767 14th August 2019 50199000 NIRDHAN UTTHAN BANK 16/14872 50401003 KISHAN LAMKI 16/20796 50601200 SAHARA CHARALI 16/22807 51299000 MAHILA SAHAYOGI BACHAT TATHA 16/26083 51499000 SHREE NAVODAYA MULTIPURPOSE CO 16/26497 51599000 UNNATI SAHAKARYA LAGHUBITTA 16/28216 51999000 SWABALAMBAN LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/33814 52399000 MIRMIRE LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/37157 28th March 2019 22nd November 52499000 INFINITY LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/39828 2019 52699000 GURANS LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/41877 7th August 2020 52799000 KANAKLAXMI SAVING & CREDIT CO. 16/43902 12th March 2021 60079203 ADHIKARI, GAJRAJ -

SANA GUTHI and the NEWARS: Impacts Of

SANA GUTHI AND THE NEWARS: Impacts of Modernization on Traditional Social Organizations Niraj Dangol Thesis Submitted for the Degree: Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education University of Tromsø Norway Autumn 2010 SANA GUTHI AND THE NEWARS: Impacts of Modernization on Traditional Social Organizations By Niraj Dangol Thesis Submitted for the Degree: Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies Faculty of Social Science, University of Tromsø Norway Autumn 2010 Supervised By Associate Professor Bjørn Bjerkli i DEDICATED TO ALL THE NEWARS “Newa: Jhi Newa: he Jui” We Newars, will always be Newars ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I regard myself fortunate for getting an opportunity to involve myself as a student of University of Tromsø. Special Thanks goes to the Sami Center for introducing the MIS program which enables the students to gain knowledge on the issues of Indigeneity and the Indigenous Peoples. I would like to express my grateful appreciation to my Supervisor, Associate Prof. Bjørn Bjerkli , for his valuable supervision and advisory role during the study. His remarkable comments and recommendations proved to be supportive for the improvisation of this study. I shall be thankful to my Father, Mr. Jitlal Dangol , for his continuous support and help throughout my thesis period. He was the one who, despite of his busy schedules, collected the supplementary materials in Kathmandu while I was writing this thesis in Tromsø. I shall be thankful to my entire family, my mother and my sisters as well, for their continuous moral support. Additionally, I thank my fiancé, Neeta Maharjan , who spent hours on internet for making valuable comments on the texts and all the suggestions and corrections on the chapters. -

Considering Dalits and Political Identity In

#$%&'#(')$#*%+,'-.+%/0$'$1.$,1/)'2,/3*%4/1& )+,4/0*%/,5'0$./14'$,0' 6+./1/)$.'/0*,1/1&'/,'/#$5/,/,5' $',*7',*6$. In this article I examine the articulation between contexts of agency within two kinds of discur- sive projects involving Dalit identity and caste relations in Nepal, so as to illuminate competing and complimentary forms of self and group identity that emerge from demarcating social perim- eters with political and economic consequences. The first involves a provocative border created around groups of people called Dalit by activists negotiating the symbols of identity politics in the country’s post-revolution democracy. Here subjective agency is expressed as political identity with attendant desires for social equality and power-sharing. The second context of Dalit agency emerges between people and groups as they engage in inter caste economic exchanges called riti maagnay in mixed caste communities that subsist on interdependent farming and artisan activi- ties. Here caste distinctions are evoked through performed communicative agency that both resists domination and affirms status difference. Through this examination we find the rural terrain that is home to landless and poor rural Dalits only partially mirrors that evoked by Dalit activists as they struggle to craft modern identities. The sources of data analyzed include ethnographic field research conducted during various periods from 1988-2005, and discussions that transpired through- out 2007 among Dalit activist members of an internet discussion group called nepaldalitinfo. -

Identity-Based Conflict and the Role of Print Media in the Pahadi Community of Contemporary Nepal Sunil Kumar Pokhrel Kennesaw State University

Kennesaw State University DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University Dissertations, Theses and Capstone Projects 7-2015 Identity-Based Conflict and the Role of Print Media in the Pahadi Community of Contemporary Nepal Sunil Kumar Pokhrel Kennesaw State University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/etd Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Pokhrel, Sunil Kumar, "Identity-Based Conflict and the Role of Print Media in the Pahadi Community of Contemporary Nepal" (2015). Dissertations, Theses and Capstone Projects. Paper 673. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses and Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IDENTITY-BASED CONFLICT AND PRINT MEDIA IDENTITY-BASED CONFLICT AND THE ROLE OF PRINT MEDIA IN THE PAHADI COMMUNITY OF CONTEMPORARY NEPAL by SUNIL KUMAR POKHREL A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Conflict Management in the College of Humanities and Social Sciences Kennesaw State University, Kennesaw, Georgia March 2015 IDENTITY-BASED CONFLICT AND PRINT MEDIA © 2015 Sunil Kumar Pokhrel ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Recommended Citation Pokhrel, S. K. (2015). Identity-based conflict and the role of print media in the Pahadi community of contemporary Nepal. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Kennesaw State University, Kennesaw, Georgia, United States of America. IDENTITY-BASED CONFLICT AND PRINT MEDIA DEDICATION My mother and father, who encouraged me toward higher study, My wife, who always supported me in all difficult circumstances, and My sons, who trusted me during my PhD studies. -

Bhaktapur, Nepal's Cow Procession and the Improvisation of Tradition

FORGING SPACE: BHAKTAPUR, NEPAL’S COW PROCESSION AND THE IMPROVISATION OF TRADITION By: GREGORY PRICE GRIEVE Grieve, Gregory P. ―Forging a Mandalic Space: Bhaktapur, Nepal‘s Cow Procession and the Improvisation of Tradition,‖ Numen 51 (2004): 468-512. Made available courtesy of Brill Academic Publishers: http://www.brill.nl/nu ***Note: Figures may be missing from this format of the document Abstract: In 1995, as part of Bhaktapur, Nepal‘s Cow Procession, the new suburban neighborhood of Suryavinayak celebrated a ―forged‖ goat sacrifice. Forged religious practices seem enigmatic if one assumes that traditional practice consists only of the blind imitation of timeless structure. Yet, the sacrifice was not mechanical repetition; it could not be, because it was the first and only time it was celebrated. Rather, the religious performance was a conscious manipulation of available ―traditional‖ cultural logics that were strategically utilized during the Cow Procession‘s loose carnivalesque atmosphere to solve a contemporary problem—what can one do when one lives beyond the borders of religiously organized cities such as Bhaktapur? This paper argues that the ―forged‖ sacrifice was a means for this new neighborhood to operate together and improvise new mandalic space beyond the city‘s traditional cultic territory. Article: [E]very field anthropologist knows that no performance of a rite, however rigidly prescribed, is exactly the same as another performance.... Variable components make flexible the basic core of most rituals. ~Tambiah 1979:115 In Bhaktapur, Nepal around 5.30 P.M. on August 19, 1995, a castrated male goat was sacrificed to Suryavinayak, the local form of the god Ganesha.1 As part of the city‘s Cow Procession (nb. -

Locating Nepalese Mobility: a Historical Reappraisal with Reference to North East India, Burma and Tibet Gaurab KC* & Pranab Kharel**

Volume 6 Issue 2 November 2018 Kathmandu School of Law Review Locating Nepalese Mobility: A Historical Reappraisal with Reference to North East India, Burma and Tibet Gaurab KC* & Pranab Kharel** Abstract Most literature published on migration in Nepal makes the point of reference from 19th century by stressing the Lahure culture—confining the trend’s history centering itself on the 200 years of Nepali men serving in British imperial army. However, the larger story of those non-military and non-janajati (ethnic) Nepali pilgrimages, pastoralists, cultivators and tradesmen who domiciled themselves in Burma, North East India and Tibet has not been well documented in the mobility studies and is least entertained in the popular imagination. Therefore, this paper attempts to catalog this often neglected outmigration trajectory of Nepalis. Migrants venturing into Burma and North East India consist of an inclusive nature as the imperial army saw the overwhelming presence of hill janajatis in their ranks whereas Brahmins (popularly known as Bahuns) and Chettris were largely self-employed in dairy farming and animal husbandry. In tracing out the mobility of Nepalis to North East, Burma and Tibet it can be argued that the migrating population took various forms such as wanderers (later they became settlers), mercantilist, laborers, mercenary soldiers, and those settlers finally forced to become returnees. In this connection, documenting lived experiences of the living members or their ancestors is of paramount importance before the memory crosses the Rubicon. Introduction: In the contemporary Nepali landscape, the issue of migration has raised new interests for multiple actors like academicians, administrators, activists, development organizations, planners, policymakers, and students.