“Let's Drink to 1997”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

The New Hong Kong Cinema and the "Déjà Disparu" Author(S): Ackbar Abbas Source: Discourse, Vol

The New Hong Kong Cinema and the "Déjà Disparu" Author(s): Ackbar Abbas Source: Discourse, Vol. 16, No. 3 (Spring 1994), pp. 65-77 Published by: Wayne State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41389334 Accessed: 22-12-2015 11:50 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wayne State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Discourse. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.157.160.248 on Tue, 22 Dec 2015 11:50:37 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The New Hong Kong Cinema and the Déjà Disparu Ackbar Abbas I For about a decade now, it has become increasinglyapparent that a new Hong Kong cinema has been emerging.It is both a popular cinema and a cinema of auteurs,with directors like Ann Hui, Tsui Hark, Allen Fong, John Woo, Stanley Kwan, and Wong Rar-wei gaining not only local acclaim but a certain measure of interna- tional recognitionas well in the formof awards at international filmfestivals. The emergence of this new cinema can be roughly dated; twodates are significant,though in verydifferent ways. -

Hole a Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers

University of Dundee DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Going Down the 'Wabbit' Hole A Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers Barrie, Gregg Award date: 2020 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 Going Down the ‘Wabbit’ Hole: A Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers Gregg Barrie PhD Film Studies Thesis University of Dundee February 2021 Word Count – 99,996 Words 1 Going Down the ‘Wabbit’ Hole: A Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers Table of Contents Table of Figures ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Declaration ............................................................................................................................................ -

The Whistleblowers

A U S F I L M Australian Familiarisation Event Mathew Tang Producer Mathew Tang began his career in 1989 and has since worked on over 30 feature films, covering various creative and production duties that include assistant directing, line-producing, writing, directing and producing. In 1999, Mathew debuted as a screenwriter on The Kid, a film that went on to win Best Supporting Actor and Actress in the Hong Kong Film Awards. In 2005, he wrote, edited and directed his debut feature B420 which received The Grand Prix Award at the 19th Fukuoka Asian Film Festival and Best Film at the 4th Viennese Youth International Film Festival in 2007. Mathew served as Associate Producer and Line Producer on Forbidden Kingdom and oversaw the Hollywood blockbuster’s entire production in China. In 2008 and 2009 he was Vice President of Celestial Pictures. From 2009- 2012, he was the Head of Productions at EDKO Films Ltd. In the summer of 2012, he founded Movie Addict Productions and the company produced four movies. Mathew is currently an Invited Executive Member of the Hong Kong Screenwriters’ Guild and a Panel Examiner of the Hong Kong Film Development Council. Johnny Wang Line Producer Johnny Wang started working for the movie industry in 1989 and by the year 2002, he started working at Paramount Studios on the project Tomb Raider 2 as production supervisor on location in Hong Kong. Since then, he has line produced 20 movies in Hong Kong, China and other locations around the world. Johnny has been an executive board member of the HKMPEA (Hong Kong Movie Production Executives Association) for more than four years. -

The Fight Master, Spring/Summer 2007, Vol. 30 Issue 1

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Fight Master Magazine The Society of American Fight Directors Summer 2007 The Fight Master, Spring/Summer 2007, Vol. 30 Issue 1 The Society of American Fight Directors Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/fight Part of the Acting Commons, Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, Performance Studies Commons, and the Theatre History Commons THE FIGHTIGHT MASTERASTER www.safd.org Spring/Summer 2007 JournalJournal ofof thethe SocietySociety ofof AmericanAmerican FightFight DirectorsDirectors FEARLESSEARLESS ShanghaiShanghai JournalJournal PreservingPreserving ourour HistoryHistory TheThe StagesStages ofof DeathDeath FitFit forfor FightingFighting ORWARDING ETURN ERVICE EQUESTED PRSRT STD F & R S R US Postage PAID Bartlett, IL Permit No. 51 All photos by Al Foote III The Society of American Fight Directors and The University of Nevada-Las Vegas College of Fine Arts, Department of Theatre present The 2007 National Stage Combat Workshops/West July 9-27, 2007 Intermediate Actor/Combatant Workshop (IACW) Advanced Actor/Combatant Workshop (AACW) Take the next step. This workshop is designed for performers who Open to qualified actors who are well versed in a wide variety of wish to build on their existing knowledge. Students will strengthen weapons styles, this intense workshop offers the opportunity to be their skills by focusing on performance and execution of technique, challenged at a highly sophisticated level. Participants will study receive introductory training in weapon styles not offered at the technical and theatrical applications of advanced weapon styles. beginner level and the opportunity to take Skills Proficiency Tests Scene work will be an integral part of the training. Students will be toward official SAFD recognition in stage combat skills. -

A Brief Analysis of China's Contemporary Swordsmen Film

ISSN 1923-0176 [Print] Studies in Sociology of Science ISSN 1923-0184 [Online] Vol. 5, No. 4, 2014, pp. 140-143 www.cscanada.net DOI: 10.3968/5991 www.cscanada.org A Brief Analysis of China’s Contemporary Swordsmen Film ZHU Taoran[a],* ; LIU Fan[b] [a]Postgraduate, College of Arts, Southwest University, Chongqing, effects and packaging have made today’s swordsmen China. films directed by the well-known directors enjoy more [b]Associate Professor, College of Arts, Southwest University, Chongqing, China. personalized and unique styles. The concept and type of *Corresponding author. “Swordsmen” begin to be deconstructed and restructured, and the swordsmen films directed in the modern times Received 24 August 2014; accepted 10 November 2014 give us a wide variety of possibilities and ways out. No Published online 26 November 2014 matter what way does the directors use to interpret the swordsmen film in their hearts, it injects passion and Abstract vitality to China’s swordsmen film. “Chivalry, Military force, and Emotion” are not the only symbols of the traditional swordsmen film, and heroes are not omnipotent and perfect persons any more. The current 1. TSUI HARK’S IMAGINARY Chinese swordsmen film could best showcase this point, and is undergoing criticism and deconstruction. We can SWORDSMEN FILM see that a large number of Chinese directors such as Tsui Tsui Hark is a director who advocates whimsy thoughts Hark, Peter Chan, Xu Haofeng , and Wong Kar-Wai began and ridiculous ideas. He is always engaged in studying to re-examine the aesthetics and culture of swordsmen new film technology, indulging in creating new images and film after the wave of “historic costume blockbuster” in new forms of film, and continuing to provide audiences the mainland China. -

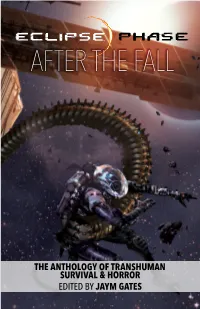

Eclipse Phase: After the Fall

AFTER THE FALL In a world of transhuman survival and horror, technology allows the re-shaping of bodies and minds, but also creates opportunities for oppression and puts the capa- AFTER THE FALL bility for mass destruction in the hands of everyone. Other threats lurk in the devastated habitats of the Fall, dangers both familiar and alien. Featuring: Madeline Ashby Rob Boyle Davidson Cole Nathaniel Dean Jack Graham Georgina Kamsika SURVIVAL &SURVIVAL HORROR Ken Liu OF ANTHOLOGY THE Karin Lowachee TRANSHUMAN Kim May Steven Mohan, Jr. Andrew Penn Romine F. Wesley Schneider Tiffany Trent Fran Wilde ECLIPSE PHASE 21950 Advance THE ANTHOLOGY OF TRANSHUMAN Reading SURVIVAL & HORROR Copy Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios EDITED BY JAYM GATES Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. Some content licensed under a Creative Commons License (BY-NC-SA); Some Rights Reserved. © 2016 AFTER THE FALL In a world of transhuman survival and horror, technology allows the re-shaping of bodies and minds, but also creates opportunities for oppression and puts the capa- AFTER THE FALL bility for mass destruction in the hands of everyone. Other threats lurk in the devastated habitats of the Fall, dangers both familiar and alien. Featuring: Madeline Ashby Rob Boyle Davidson Cole Nathaniel Dean Jack Graham Georgina Kamsika SURVIVAL &SURVIVAL HORROR Ken Liu OF ANTHOLOGY THE Karin Lowachee TRANSHUMAN Kim May Steven Mohan, Jr. Andrew Penn Romine F. Wesley Schneider Tiffany Trent Fran Wilde ECLIPSE PHASE 21950 THE ANTHOLOGY OF TRANSHUMAN SURVIVAL & HORROR Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios EDITED BY JAYM GATES Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. -

Bullet in the Head

JOHN WOO’S Bullet in the Head Tony Williams Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Tony Williams 2009 ISBN 978-962-209-968-5 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Condor Production Ltd., Hong Kong, China Contents Series Preface ix Acknowledgements xiii 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head 1 2 Bullet in the Head 23 3 Aftermath 99 Appendix 109 Notes 113 Credits 127 Filmography 129 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head Like many Hong Kong films of the 1980s and 90s, John Woo’s Bullet in the Head contains grim forebodings then held by the former colony concerning its return to Mainland China in 1997. Despite the break from Maoism following the fall of the Gang of Four and Deng Xiaoping’s movement towards capitalist modernization, the brutal events of Tiananmen Square caused great concern for a territory facing many changes in the near future. Even before these disturbing events Hong Kong’s imminent return to a motherland with a different dialect and social customs evoked insecurity on the part of a population still remembering the violent events of the Cultural Revolution as well as the Maoist- inspired riots that affected the colony in 1967. -

Gender and the Family in Contemporary Chinese-Language Film Remakes

Gender and the family in contemporary Chinese-language film remakes Sarah Woodland BBusMan., BA (Hons) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2016 School of Languages and Cultures 1 Abstract This thesis argues that cinematic remakes in the Chinese cultural context are a far more complex phenomenon than adaptive translation between disparate cultures. While early work conducted on French cinema and recent work on Chinese-language remakes by scholars including Li, Chan and Wang focused primarily on issues of intercultural difference, this thesis looks not only at remaking across cultures, but also at intracultural remakes. In doing so, it moves beyond questions of cultural politics, taking full advantage of the unique opportunity provided by remakes to compare and contrast two versions of the same narrative, and investigates more broadly at the many reasons why changes between a source film and remake might occur. Using gender as a lens through which these changes can be observed, this thesis conducts a comparative analysis of two pairs of intercultural and two pairs of intracultural films, each chapter highlighting a different dimension of remakes, and illustrating how changes in gender representations can be reflective not just of differences in attitudes towards gender across cultures, but also of broader concerns relating to culture, genre, auteurism, politics and temporality. The thesis endeavours to investigate the complexities of remaking processes in a Chinese-language cinematic context, with a view to exploring the ways in which remakes might reflect different perspectives on Chinese society more broadly, through their ability to compel the viewer to reflect not only on the past, by virtue of the relationship with a source text, but also on the present, through the way in which the remake reshapes this text to address its audience. -

Special Issue Taiwan and Ireland In

TAIWAN IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE Taiwan in Comparative Perspective is the first scholarly journal based outside Taiwan to contextualize processes of modernization and globalization through interdisciplinary studies of significant issues that use Taiwan as a point of comparison. The primary aim of the Journal is to promote grounded, critical, and contextualized analysis in English of economic, political, societal, and environmental change from a cultural perspective, while locating modern Taiwan in its Asian and global contexts. The history and position of Taiwan make it a particularly interesting location from which to examine the dynamics and interactions of our globalizing world. In addition, the Journal seeks to use the study of Taiwan as a fulcrum for discussing theoretical and methodological questions pertinent not only to the study of Taiwan but to the study of cultures and societies more generally. Thereby the rationale of Taiwan in Comparative Perspective is to act as a forum and catalyst for the development of new theoretical and methodological perspectives generated via critical scrutiny of the particular experience of Taiwan in an increasingly unstable and fragmented world. Editor-in-chief Stephan Feuchtwang (London School of Economics, UK) Editor Fang-Long Shih (London School of Economics, UK) Managing Editor R.E. Bartholomew (LSE Taiwan Research Programme) Editorial Board Chris Berry (Film and Television Studies, Goldsmiths College, UK) Hsin-Huang Michael Hsiao (Sociology and Civil Society, Academia Sinica, Taiwan) Sung-sheng Yvonne Chang (Comparative Literature, University of Texas, USA) Kent Deng (Economic History, London School of Economics, UK) Bernhard Fuehrer (Sinology and Philosophy, School of Oriental and African Studies, UK) Mark Harrison (Asian Languages and Studies, University of Tasmania, Australia) Bob Jessop (Political Sociology, Lancaster University, UK) Paul R. -

East Bay Deputy Held in Drug Case Arrest Linked to Ongoing State Narcotics Agent Probe

Sunday, March 6, 2011 California’s Best Large Newspaper as named by the California Newspaper Publishers Association | $3.00 Gxxxxx• TOP OF THE NEWS Insight Bay Area Magazine WikiLeaks — 1 Newsom: Concerns Spring adventure World rise over S.F. office deal 1 Libya uprising: Reb- How Europe with donor. C1 tours from the els capture a key oil port caves in to U.S. 1 Shipping: Nancy Pelo- Galapagos to while state forces un- si extols the importance leash mortar fire. A5 pressure. F6 of local ports. C1 South Africa. 6 Sporting Green Food & Wine Business Travel 1 Scouting triumph: 1 Larry Goldfarb: Marin The Giants picked All about falafel County hedge fund manager Special Hawaii rapidly rising prospect who settled fraud charges Brandon Belt, right, — with three stretched the truth about section touts 147th in the ’09 draft. B1 recipes. H1 charitable donations. D1 Kailua-Kona. M1 RECOVERY East Bay deputy held in drug case Arrest linked to ongoing state narcotics agent probe By Justin Berton custody by agents representing CHRONICLE STAFF WRITER the state Department of Justice and the district attorney’s of- A Contra Costa County sher- fice. iff’s deputy has been arrested in Authorities did not elaborate connection with the investiga- on the details of the alleged tion of a state narcotics agent offenses, but a statement from who allegedly stole drugs from the Contra Costa County Sher- Michael Macor / The Chronicle evidence lockers, authorities iff’s Department said Tanabe’s Chris Rodriguez (4) of the Bay Cruisers shoots over Spencer Halsop (24) of the Utah Jazz said Saturday. -

De Draagbare Wikipedia Van Het Schrijven – Verhaal

DE DRAAGBARE WIKIPEDIA VAN HET SCHRIJVEN VERHAAL BRON: WIKIPEDIA SAMENGESTELD DOOR PETER KAPTEIN 1 Gebruik, verspreiding en verantwoording: Dit boek mag zonder kosten of restricties: Naar eigen inzicht en via alle mogelijke middelen gekopieerd en verspreid worden naar iedereen die daar belangstelling in heeft Gebruikt worden als materiaal voor workshops en lessen Uitgeprint worden op papier Dit boek (en het materiaal in dit boek) is gratis door mij (de samensteller) ter beschikking gesteld voor jou (de lezer en gebruiker) en niet bestemd voor verkoop door derden. Licentie: Creative Commons Naamsvermelding / Gelijk Delen. De meeste bronnen van de gebruikte tekst zijn artikelen van Wikipedia, met uitzondering van de inleiding, het hoofdstuk Redigeren en Keuze van vertelstem. Deze informatie kon niet op Wikipedia gevonden worden en is van eigen hand. Engels In een aantal gevallen is de Nederlandse tekst te kort of non-specifiek en heb ik gekozen voor de Engelse variant. Mag dat zomaar met Wikipedia artikelen? Ja. WikiPedia gebruikt de Creative Commons Naamsvermelding / Gelijk Delen. Dit houdt in dat het is toegestaan om: Het werk te delen Het werk te bewerken Onder de volgende voorwaarden: Naamsvermelding (in dit geval: Wikipedia) Gelijk Delen (verspreid onder dezelfde licentie als Wikipedia) Link naar de licentie: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.nl Versie: Mei 2014, Peter Kaptein 2 INHOUDSOPGAVE INLEIDING 12 KRITIEK EN VERHAALANALYSE 16 Literaire stromingen 17 Romantiek 19 Classicisme 21 Realisme 24 Naturalisme 25