Getting Started with Intercultural Language Learning a Resource for Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20 Top-Ten Shot

Last Updated – 21.10.2015 EUROPEAN ALL TIME RANKINGS MEN SHOT PUT M35 – 39 (Weight 7.250 kg) DISTANCE NAME NATION BORN MEET PLACE MEET DATE 22.10 Andrei Mikhnevich BLR 12.07.1976 Minsk 11.08.2011 21.35 Aleksander Baryshnikov RUS 11.11.1948 Sochi 10.06.1984 20.91 Dragan Perić SRB 08.05.1964 Edmonton 04.08.2001 20.90 Saulius Kleiza LTU 02.04.1964 Kaunas 14.05.1999 20.84 Matti Yrjölä FIN 26.03.1938 Kobemäki 06.07.1976 20.79 Milan Haborak SVK 11.01.1973 Pacov 11.07.2008 20.78 Roman Virastyuk UKR 20.04.1968 Kiev 03.07.2003 20.70 Wladyslaw Komar POL 11.04.1940 Chemnitz 26.06.1977 20.67 Hamza Alic BIH 20.01.1979 Bistrica 30.05.2015 20.54 Jovan Lazarevic SRB 03.05.1952 Minsk 26.07.1990 INDOOR 21.04 Gheorghe Guset ROU 18.05.1968 Bucarest 18.02.2006 20.85 Mark Proctor GBR 15.01.1963 Kings Lynn 18.01.1998 20.76 Valery Voykin RUS 14.10.1945 Leningrado 29.01.1983 * * * SHOT PUT M40 – 44 (Weight 7.250 kg) DISTANCE NAME NATION BORN MEET PLACE MEET DATE 20.44 Ivan Ivancic SRB 06.12.1937 Beograd 05.07.1980 20.34 Dragan Perić SRB 08.05.1964 Zenica 02.09.2006 20.04 Mark Proctor GBR 15.01.1963 Manchester 30.08.2005 19.97 Waldyslaw Komar POL 11.04.1940 Warsaw 06.09.1980 19.77 Pierre Colnard FRA 18.02.1929 Colombes 18.07.1970 19.18 Matti Yrjölä FIN 26.03.1938 Somero 16.07.1978 19.10 Paolo Dal Soglio ITA 29.07.1970 Savona 10.06.2012 19.09 Ferdinand Schladen GER 24.05.1939 Höhr 06.09.1981 19.08 Paul Edwards GBR 16.02.1959 Luton 16.06.1999 19.07 Alessandro Andrei ITA 03.01.1959 Pescara 23.07.2000 INDOOR 19.48 Ivan Ivancic SRB 06.12.1937 Sindelfingen 02.03.1980 * * * SHOT PUT M45 – 49 (Weight 7.250 kg) DISTANCE NAME NATION BORN MEET PLACE MEET DATE 20.77 Ivan Ivancic SRB 06.12.1937 Coblenz 31.08.1983 18.22 Gudmund. -

LIBRARY All Rights Reserved

LIBRARY All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if materia! had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 fA NEW DAWN RISING':1 AN EMPIRICAL AND SOCIAL STUDY CONCERNING THE EMERGENCE AND DEVELOPMENT OF ENGLISH WOMEN'S ATHLETICS UNTIL 1980 Gregory Paul Moon Submitted in part fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Roehampton Institute London for the University of Surrey August 1997 1Sutton and Cheam Advertiser 1979. Dawn Lucy (later Gaskin) was the first athlete I ever coached. Previously, she had made little progress for several years. In our first season together her improvement was such that the local newspaper was prompted to address her performances with this headline. ABSTRACT This study explores the history of English women's athletics, from the earliest references up to 1980. There is detailed discussion of smock racing and pedestrianism during the eighteenth- and nineteenth-centuries, but attention is focused on the period from 1921, when international and then domestic governing bodies were formed and athletics .became established as a legitimate sporting activity for women. -

Peso Olímpico. Datos Mujeres

LOS LANZAMIENTOS EN LOS JJOO PROGRESIÓN RECORD OLÍMPICO JUEGOS OLÍMPICOS. PODIUM LANZAMIENTO DE PESO. MUJERES LANZAMIENTO DE PESO MUJERES • 13.14 Micheline Ostermeyer FRA London Aug 04, 1948 SEDE ORO PLATA BRONCE • 13.75 Micheline Ostermeyer FRA London Aug 04, 1948 London 1948 Micheline Ostermeyer FRA 13,75 Amelia Piccinini ITA 13,09 Ine Schäffer AUT 13,08 • 13.88 Klavdiya Tochenova URS Helsinki Jul 26, 1952 Helsinki 1952 Galina Zybina URS 15,28 Marianne Werner FRG 14,57 Klavdiya Tochenova URS 14,50 • 13.89 Marianne Werner FRG Helsinki Jul 26, 1952 Melbourne 1956 Tamara Tishkevich URS 16,59 Galina Zybina URS 16,53 Marianne Werner FRG 15,61 • 15.00 Galina Zybina URS Helsinki Jul 26, 1952 Rome 1960 Tamara Press URS 17,32 Johanna Lüttge GDR 16,61 Earlene Brown USA 16,42 • 15.28 Galina Zybina URS Helsinki Jul 26, 1952 Tokyo 1964 Tamara Press URS 18,14 Renate Garisch GDR 17,61 Galina Zybina URS 17,45 • 16.35 Galina Zybina URS Melbourne Nov 30, 1956 Mexico 1968 Margitta Gummel GDR 19,61 Marita Lange GDR 18,78 Nadezhda Chizhova URS 18,19 • 16.48 Galina Zybina URS Melbourne Nov 30, 1956 Munich 1972 Nadezhda Chizhova URS 21,03 Margitta Gummel GDR 20,22 Ivanka Khristova BUL 19,35 • 16.53 Galina Zybina URS Melbourne Nov 30, 1956 Montreal 1976 Ivanka Khristova BUL 21,16 Nadezhda Chizhova URS 20,96 Helena Fibingerova TCH 20,67 • 16.59 Tamara Tishkevich URS Melbourne Nov 30, 1956 Moscow 1980 Ilona Slupianek GDR 22,41 Esfir Krachevskaya URS 21,42 Margitta Pufe GDR 21,20 • 17.32 Tamara Press URS Rome Sep 02, 1960 Los Angeles 1984 Claudia Losch FRG 20,48 -

Downloadable Results (Pdf)

Muller British Athletics Championships Manchester Regional Arena Heptathlon From Friday 25 June to Sunday 27 June 2021 Women 's Shot Put LETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS RESULTS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS 26 June 2021 TIME TEMPERATURE Start 15:30 14°C 78 % End 15:5214°C 78 % MARK COMPETITOR NAT AGE Record Date WR22.63 Natalya LISOVSKAYA URS 24 7 Jun 1987 NR19.36 Judy OAKES GBR 30 14 Aug 1988 CR18.76 Judy OAKES GBR 30 6 Aug 1988 SR17.88 Sophie MCKINNA GBR 26 4 Sep 2020 POSSTART COMPETITOR AGE MARK POINTS 1 3 Ellen BARBER 23 13.30 747 YEOVIL 2 6 Katie STAINTON 26 12.02 662 SB BIRCHFIELD HARRIERS 3 2 Natasha SMITH 21 12.01 662 SB BIRCHFIELD HARRIERS 4 8 Ashleigh SPILIOPOULOU 22 10.88 587 ENFIELD & HARINGEY H 5 7 Ella RUSH 17 10.54 565 AMBER VALLEY 6 5 Emily TYRRELL 19 9.43 492 TEAM BATH 7 1 Emma CANNING 24 8.18 411 EDINBURGH AC 4 Amaya SCOTT-RULE 20 DNS 0 SOUTHAMPTON SERIES 1 2 3 1 Emma CANNING EDAC X 8.18 X 2 Natasha SMITH BIRCHFIELD 11.57 12.01 11.45 3 Ellen BARBER YEOVIL 13.09 13.22 13.30 4 Amaya SCOTT-RULE SOTON 5 Emily TYRRELL BATH X 8.70 9.43 6 Katie STAINTON BIRCHFIELD 12.02 11.98 X 7 Ella RUSH AMBER V 10.54 X X 8 Ashleigh SPILIOPOULOU ENFIELD 10.88 10.83 10.27 GREAT BRITAIN & N.I. -

Downloadable Results (Pdf)

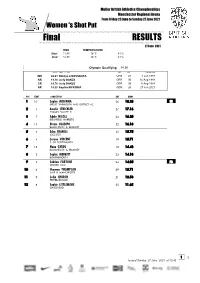

Muller British Athletics Championships Manchester Regional Arena From Friday 25 June to Sunday 27 June 2021 Women 's Shot Put HLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS Final RESULTS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS ATHLETICS A 27 June 2021 TIME TEMPERATURE Start 11:38 16°C 81 % End 12:3816°C 81 % Olympic Qualifying 18.50 MARK COMPETITOR NAT AGE Record Date WR22.63 Natalya LISOVSKAYA URS 24 7 Jun 1987 NR19.36 Judy OAKES GBR 30 14 Aug 1988 CR18.76 Judy OAKES GBR 30 6 Aug 1988 SR18.28 Sophie MCKINNA GBR 26 27 Jun 2021 POSSTART COMPETITOR AGE MARK 1 10 Sophie MCKINNA 26 18.28 SR GREAT YARMOUTH AND DISTRICT AC 2 5 Amelia STRICKLER 27 17.16 THAMES VALLEY H 3 7 Adele NICOLL 24 16.20 BIRCHFIELD HARRIERS 4 11 Divine OLADIPO 22 16.18 BLACKHEATH & BROMLEY 5 3 Eden FRANCIS 32 15.75 LEICESTER 6 4 Serena VINCENT 19 15.71 C OF PORTSMOUTH 7 12 Nana GYEDU 18 14.48 BLACKHEATH & BROMLEY 8 2 Sophie MERRITT 23 14.18 BOURNEMOUTH 9 1 Sabrina FORTUNE 24 14.05 PB DEESIDE AAC 10 6 Shaunna THOMPSON 29 13.71 SALE H MANCHESTER 11 9 Lydia CHURCH 21 12.53 PETERBOROUGH 12 8 Sophie LITTLEMORE 25 11.65 GATESHEAD 1 2 Issued Sunday, 27 June 2021 at 12:42 Shot Put Women - Final RESULTS SERIES 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 Sabrina FORTUNE DEESIDE 13.62 14.05 13.15 -

Spring 2010 U.S

IN THIS ISSUE SPRING 2010 School w ota La ota nes Min of y sit ver Uni the for e Magazin The Alumni fight for human rights on U.S. and global fronts. Former Justice O’Connor Visits • Justice Thomas Seminar • Legal Aid for Mille Lacs Band • Summer CLE Rights on Their Side S P R I N G 2 0 1 0 Perspectives FORMER JUSTICE O’CONNOR VISITS • JUSTICE THOMAS SEMINAR• LEGAL AID FOR MILLE LACS BAND www.law.umn.edu PAID U.S. Postage Permit No. 155 Nonprofit Org. Minneapolis, MN N225 Mondale Hall 229 19th Avenue South Minneapolis, MN 55455 Partners in Excellence Annual Fund Update Dear Friends and Fellow Alumni: As National Co-Chairs of this year’s Partners in DEAN LAW ALUMNI BOARD AND Excellence annual fund drive, we are pleased that many David Wippman BOARD OF VISITORS 2009-10 of you have chosen to benefit the Law School with Grant Aldonas (’79) your generosity through gifts to the Law School Fund. ASSISTANT DEAN AND Deborah Amberg (’90)† In this time of varied economic challenges, you have CHIEF OF STAFF Austin Anderson (’58) recognized the importance of contributing to the Law Nora Klaphake Justice Paul Anderson (’68) School, particularly in light of rapidly dwindling state Former Chief Justice support. We thank all of you who have given so far DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS Russell Anderson (’68) and wish to specially acknowledge the generosity of Cynthia Huff Albert (Andy) Andrews (’66)† this year’s Fraser Scholars and Dean’s Circle donors James J. Bender (’81) (through April 15, 2010). -

Etn2000 12(Og)

■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■ Volume 46, No. 12 NEWSLETTERNEWSLETTER ■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■track October 31, 2000 II(0.3)–1. Boldon 10.11; 2. Collins 10.19; 3. Surin 10.20; 4. Gardener 10.27; 5. Williams 10.30; 6. Mayola 10.35; 7. Balcerzak 10.38; 8. — Olympic Games — Lachkovics 10.44; 9. Batangdon 10.52. III(0.8)–1. Thompson 10.04; 2. Shirvington 10.13; 3. Zakari 10.22; 4. Frater 10.23; 5. de SYDNEY, Australia, September 22–25, 10.42; 4. Tommy Kafri (Isr) 10.43; 5. Christian Lima 10.28; 6. Patros 10.33; 7. Rurak 10.38; 8. 27–October 1. Nsiah (Gha) 10.44; 6. Francesco Scuderi (Ita) Bailey 11.36. Attendance: 9/22—97,432/102,485; 9/23— 10.50; 7. Idrissa Sanou (BkF) 10.60; 8. Yous- IV(0.8)–1. Chambers 10.12; 2. Drummond 92,655/104,228; 9/24—85,806/101,772; 9/ souf Simpara (Mli) 10.82;… dnf—Ronald Pro- 10.15; 3. Ito 10.25; 4. Buckland 10.26; 5. Bous- 25—92,154/112,524; 9/27—96,127/102,844; messe (StL). sombo 10.27; 6. Tilli 10.27; 7. Quinn 10.27; 8. 9/28—89,254/106,106; 9/29—94,127/99,428; VI(0.2)–1. Greene 10.31; 2. Collins 10.39; 3. Jarrett 16.40. 9/30—105,448; 10/1—(marathon finish and Joseph Batangdon (Cmr) 10.45; 4. Andrea V(0.2)–1. Campbell 10.21; 2. C. Johnson Closing Ceremonies) 114,714. Colombo (Ita) 10.52; 5. Watson Nyambek (Mal) 10.24; 3. -

An Economic Analysis of the Effects of Steroids on Season Best Performances in Track and Field

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU Honors Projects Economics Department 4-21-2008 An Economic Analysis of the Effects of Steroids on Season Best Performances in Track and Field Allison Fisher '08 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/econ_honproj Part of the Economics Commons Recommended Citation Fisher '08, Allison, "An Economic Analysis of the Effects of Steroids on Season Best Performances in Track and Field" (2008). Honors Projects. 86. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/econ_honproj/86 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. "An Economic Analysis ofthe Effects of Steroids on Season Best Performances in Track and Field" Allison Fisher Faculty Advisor- Michael Seeborg April 21, 2008 , This paper investigates the relationship between steroids and an athlete's ability to run a season best time in track and field. Certain event groups have seen a faster drop in season bests than others. Medical research indicates which ofthese event groups (sprinters, distance, throwers, jumpers) would most benefit from steroids. -

1994 Commonwealth Games - MEN 1994 Commonwealth Games - MEN Victoria, BC - CANADA Mens - 100M Final 1

1994 Commonwealth Games - MEN 1994 Commonwealth Games - MEN Victoria, BC - CANADA Mens - 100m Final 1. Linford CHRISTIE ENG 9.91 NGR 2. Michael GREEN JAM 10.05 3. Frankie FREDERICKS NAM 10.06 4. Ato BOLDON TRI 10.07 5. Glenroy GILBERT CAN 10.11 6. Olapade ADENIKEN NIG 10.11 7. Augustine NKETIA NEW 10.42 Horace DOVE-EDWIN SIE Back To Top Of Page -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Mens - 200m Final 1. Frankie FREDERICKS NAM 19.97 NGR 2. John REGIS ENG 20.25 3. Daniel EFFIONG NIG 20.40 4. Damien MARSH AUS 20.54 5. Terry WILLIAMS ENG 20.62 6. Kayode OLUYEMI NIG 20.64 7. Stephen BRIMACOMBE AUS 20.67 8. Troy DOUGLAS BER 20.71 Back To Top Of Page -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Mens - 400m Final 1. Charles GITONGA KEN 45.00 2. Duaine LADEJO ENG 45.11 3. Sunday BADA NIG 45.45 4. Paul GREENE AUS 45.50 5. Patrick DELICE TRI 45.89 6. Eswort COOMBS ST 45.96 7. Neil DE SILVA TRI 46.27 8. Bobang PHIRI SOU 46.35 Back To Top Of Page -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Mens - 800m Final 1. Patrick KONCHELLAH KEN 1:45.18 2. Hezekiel SEPENG SOU 1:45.76 3. Savieri NGIDHI ZIM 1:46.06 4. Craig WINROW ENG 1:46.91 5. Brendan HANIGAN AUS 1:47.24 6. William SEREM KEN 1:47.30 7. Martin STEELE ENG 1:48.04 8. Thomas MCKEAN SCO 1:50.81 Back To Top Of Page -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Mens - 1,500m Final 1. Reuben CHESANG KEN 3:36.70 2. Kevin SULLIVAN CAN 3:36.78 3. -

2018 World Indoor Championships Statistics - Women’S SP - by K Ken Nakamura Summary Page

2018 World Indoor Championships Statistics - Women’s SP - by K Ken Nakamura Summary Page: All time Performance List at the World Indoor Championships Performance Performer Dist Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 20.85 Nadzeya Ostapchuk BLR 1 Doha 2010 2 2 20.67 Valerie Adams NZL 1 Sopot 2014 3 3 20.55 Irina Korzhanenko RUS 1 Birmingham 2003 4 4 20.54 Sui Xinmei CHN 1 Sevilla 1991 4 20.54 Valerie Adams 1 Istanbul 2012 6 5 20.52 Natalya Lisovskaya URS 1 Indianapolis 1987 Shortest winning throw: 19.08m by Svetlana Krivelyova (RUS) in 1999 is the shortest, while 19.40m by Kathrin Neimke (GER) in 1995 is the second shortest winning throw Margin of Victory Difference Dist Name Nat Venue Year Max 88cm 20.21m Michelle Carter USA Portland 2016 73cm 20.67m Valerie Adams NZL Sopot 2014 Min 8cm 20.00m Vita Pavlyshi UKR Paris 1997 19.08m Svetlana Krivelyova RUS Maebashi 1999 12cm 20.54m Valerie Adams NZL Istanbul 2012 Best Marks for Places in the World Indoor Championships Pos Distance Name Nat Venue Year 1 20.85 Nadzeya Ostapchuk BLR Doha 2010 2 20.49 Valerie Adams NZL Doha 2010 3 20.42 Natallia Mikhnevich BLR Doha 2010 Multiple Gold Medalists: Valerie Adams Vili (NZL): 2008, 2012, 2014 Svetlana Krivelyova (RUS): 1993, 1999, 2004 Natalya Lisovskaya (URS): 1985**, 1987 **1985 World Indoor Games GBR All-Comer’s Indoor List Performance Performer Dist Name Nat Pos Venue DMY 1 1 21.45 Ilona Briesenick GDR 1 Cosford 28 Feb 1979 2 2 20.70 Nat alya Lisovskaya URS 1 Cosford 23 Feb 1983 Longest throws in March (only indoor performances are listed) Performance Performer -

Etn1985 17 Eurojr GP Final

September 12, 1985 Volume 31, No. 17 • EUROPEAN JUNIOR CHAMPIONSHIPS• •MEN• LJ, Mai (EG) 26-2¾ (25-11½, f, 25-6¾, 100H(2,0), Mo. Ewanje-Epee (Fra) 13.10 26-2¼, 26-2¾, 26-¾); 2. Oetongs (EG) 26-1½w e EJA (2, 2 WJ); 2. Tillack (EG) 13.24 (=6, =11, (25-9¼); 3. Mellaard (Hol) 25-6¾; 4. Voloshin Cottbus, East Germany, August 22-25 WJ); 3. Okolo-Kulak (SU) 13.30 (=12, x WJ); 4. (SU) 25-6¾; 5. Haaf (WG) 25-1¾; 6. Shivitskiy Petrikova (Cze) 13.48; 5. Skeet (GB) 13.51; 6. (8/22-100, 10kmW, DT; 8/23-1500, 110H, (SU) 24-8¼. HJ, LJ, HT, Dec; 8/24- 400, 2000St, 5000, Lippe (WG) 13.54. T J, Mai 55-6½ (54-10¼, 54-10, f, 55-2¾, PV)- Heats: 11(0.6)-1. Ewanje•Epee 13.29 (10, x 55-1, 55-6½); 2. Gorbachenko (SU) 54-6; 3. All athletes born 1966 or later. WJ). Semis: 11(1.3)-1. Ewanje-Epee 13.21 (4, Weremczuk (Pol) 53-2¼; 4. Chopov (Bui) =7 WJ). 100(0.7), Bunney (GB) 10.38; 2. Havas 52-1¼; 5. Lynch (GB) 51-3½; 6. Porier (Fra) e 400H, Bartl (EG) 56.22 (3, 10 WJ); 2. (Hun) 10.40; 3. Regis (GB) 10.51; 4. Savin 50-9¼. (SU) 10.54; 5. Queneherve (Fra) 10.55; 6. Petkova (Bui) 56.50 (5, x WJ); 3. Zwiener (WG) Schlicht (WG) 10.58. SP, Buder (EG) 63-5½ (62·5¼, 63-5~, f, 57. 78; 4. -

The BG News August 26, 1994

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 8-26-1994 The BG News August 26, 1994 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News August 26, 1994" (1994). BG News (Student Newspaper). 5716. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/5716 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. fi The BG News 'A Commitment to Excellence" Friday, August 26, 1994 Bowling Green, Ohio Volume 80, Issue 3 Fewer women rush sororities Senate passes $30 Misconceptions about Greek life may be cause of drop billion crime bill byJImVlcken The BC News after heated debate The number of women par- by Carolyn Skorneck ate Republicans in the House. ticipating in fall Sorority Rush The Associated Press Clinton immediately marched has dropped by more than SO to the White House lawn to praise percent in the past six years, the lawmakers and share In the according to figures obtained WASHINGTON - Capping a glow of their work. from the Office of Greek Life ferocious six-year debate, Con- "Today, senators of both par- and Residential Services. gress handed President Clinton a ties took a brave and promising This year, 269 women partic- critical victory Thursday night step to bring the long hard wait ipated in Sorority Rush, which with Senate passage of a $30 bil- for a crime bill closer to an end," is 331 less than the number lion, more- that participated in 1988.