16 the Dingo Barrier Fence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sturt National Park

Plan of Management Sturt National Park © 2018 State of NSW and the Office of Environment and Heritage With the exception of photographs, the State of NSW and the Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH) are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs. OEH has compiled this publication in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. OEH shall not be liable for any damage that may occur to any person or organisation taking action or not on the basis of this publication. All content in this publication is owned by OEH and is protected by Crown Copyright. It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) , subject to the exemptions contained in the licence. The legal code for the licence is available at Creative Commons . OEH asserts the right to be attributed as author of the original material in the following manner: © State of New South Wales and Office of Environment and Heritage 2018. This plan of management was adopted by the Minister for the Environment on 23 January 2018. Acknowledgments OEH acknowledges that Sturt is in the traditional Country of the Wangkumara and Malyangapa people. This plan of management was prepared by staff of the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS), part of OEH. -

Biological Conservation 232 (2019) 187–193

Biological Conservation 232 (2019) 187–193 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon A palaeontological perspective on the proposal to reintroduce Tasmanian devils to mainland Australia to suppress invasive predators T ⁎ Michael C. Westawaya, , Gilbert Priceb, Tony Miscamblec, Jane McDonaldb, Jonathon Crambb, ⁎ Jeremy Ringmad, Rainer Grüna, Darryl Jonesa, Mark Collarde, a Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution, Environmental Futures Research Institute, N13 Environment 2 Building, Griffith University, Nathan Campus, 170 Kessels Road, Nathan, Brisbane, Queensland 4111, Australia b School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Queensland, St. Lucia, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia c School of Social Science, University of Queensland, St. Lucia, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia d College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources, University of Hawai‘i at Manoa, 2500 Campus Road, Honolulu, Hawai'i 96822, USA e Department of Archaeology, Simon Fraser University, 8888 University Drive, Burnaby, British Columbia V5A 1S6, Canada ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The diversity of Australia's mammalian fauna has decreased markedly since European colonisation. Species in Australia the small-to-medium body size range have been particularly badly affected. Feral cats and foxes have played a Invasive predator central role in this decline and consequently strategies for reducing their numbers are being evaluated. One such Fossil record strategy is the reintroduction to the mainland of the Tasmanian devil, Sarcophilus harrisii. Here, we provide a Feral cat palaeontological perspective on this proposal. We begin by collating published records of devil remains in Fox Quaternary deposits. These data show that the range of devils once spanned all the main ecological zones in Tasmanian devil Sarcophilus Australia. -

Cost Effective Feral Animal Exclusion Fencing for Areas of High

Cost Effective Feral Animal Exclusion Fencing for Areas of High Conservation Value in Australia Cost Effective Feral Animal Exclusion Fencing for Areas of High Conservation Value in Australia A report for the: Australian Government The Department of the Environment and Heritage Prepared by: Kirstin Long and Alan Robley Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Department of Sustainability and Environment Heidelberg, Melbourne July 2004 Cost Effective Feral Animal Exclusion Fencing for Areas of High Conservation Value in Australia by Long, K and Robley, A. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for the Environment and Heritage. While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. ISBN: 0642 549923 Published July 2004 © Commonwealth of Australia 2004 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth, available from the Department of the Environment and Heritage. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Director Threat Abatement -

SHEEP, DINGOES and KANGAROOS: NEW CHALLENGES and a CHANGE of DIRECTION 20 YEARS on Peter Clark1, Elizabeth Clark1 and Benjamin L

Citation: Clark P, Clark E, Allen BL (2018). Sheep, dingoes and kangaroos: new challenges and a change of direction 20 years on. In 'Advances in conservation through sustainable use of wildlife.' Eds G Baxter, N Finch, P Murray. pp. 173–178 (University of Queensland: Brisbane). Available online at: https://onlineshop.ssaa.org.au/product-category/publications/ SHEEP, DINGOES AND KANGAROOS: NEW CHALLENGES AND A CHANGE OF DIRECTION 20 YEARS ON Peter Clark1, Elizabeth Clark1 and Benjamin L. Allen2* 1Leander Station, Longreach, Queensland 4730, Australia. Email: [email protected] 2University of Southern Queensland, Institute for Agriculture and the Environment, Toowoomba, Queensland 4350. Email: [email protected] *Corresponding author. ABSTRACT Predation and competition are two primary forces limiting the extent to which sheep can be grazed in the Australian rangelands, particularly in Queensland. Dingo predation has been non-existent in much of the sheep zone since the localised eradication of dingoes in the early 1900s. Competition with kangaroos has been ever-present, but was previously managed (to some extent) by the commercial kangaroo harvesting industry. However, changes to dingo distribution and kangaroo densities and harvesting over the last 20 years have meant that dingo predation and kangaroo competition again threaten viable sheep production in the rangelands. Dingoes have increased their distribution and density in almost all sheep grazing areas and contemporary lethal control efforts are not preventing the decline of sheep. Loss of valuable international markets and moves to now harvest only adult male kangaroos means that the kangaroo harvesting industry produces little relief from kangaroo grazing pressure (given that kangaroo population growth is little affected by removal of adult males; see Finch et al. -

Your Complete Guide to Broken Hill and The

YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO DESTINATION BROKEN HILL Mundi Mundi Plains Broken Hill 2 City Map 4–7 Getting There and Around 8 HistoriC Lustre 10 Explore & Discover 14 Take a Walk... 20 Arts & Culture 28 Eat & Drink 36 Silverton Places to Stay 42 Shopping 48 Silverton prospects 50 Corner Country 54 The Outback & National Parks 58 Touring RoutEs 66 Regional Map 80 Broken Hill is on Australian Living Desert State Park Central Standard Time so make Line of Lode Miners Memorial sure you adjust your clocks to suit. « Have a safe and happy journey! Your feedback about this guide is encouraged. Every endeavour has been made to ensure that the details appearing in this publication are correct at the time of printing, but we can accept no responsibility for inaccuracies. Photography has been provided by Broken Hill City Council, Destination NSW, NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service, Simon Bayliss, The Nomad Company, Silverton Photography Gallery and other contributors. This visitor guide has been designed by Gang Gang Graphics and produced by Pace Advertising Pty. Ltd. ABN 44 005 361 768 Tel 03 5273 4777 W pace.com.au E [email protected] Copyright 2020 Destination Broken Hill. 1 Looking out from the Line Declared Australia’s first heritage-listed of Lode Miners Memorial city in 2015, its physical and natural charm is compelling, but you’ll soon discover what the locals have always known – that Broken Hill’s greatest asset is its people. Its isolation in a breathtakingly spectacular, rugged and harsh terrain means people who live here are resilient and have a robust sense of community – they embrace life, are self-sufficient and make things happen, but Broken Hill’s unique they’ve always got time for each other and if you’re from Welcome to out of town, it doesn’t take long to be embraced in the blend of Aboriginal and city’s characteristic old-world hospitality. -

Detective Work Across Dingo Fence Reveals New Factor in Woody Shrub Invasion 5 December 2016

Detective work across dingo fence reveals new factor in woody shrub invasion 5 December 2016 author UNSW Associate Professor Mike Letnic. "These weeds reduce the availability of feed for livestock and hinder access for mustering. But removing them is contentious, because they are classified as native vegetation." To measure the encroachment of woody shrubs into grasslands, the researchers, led by PhD candidate Christopher Gordon from Western Sydney University, examined aerial photographs of far western NSW and eastern South Australia spanning a 50 year period. A dusky hopping mouse which eats the seeds of woody shrubs in semi-arid Australia. Credit: Ben Moore Extermination of dingoes and the consequent loss of small mammals - not just overgrazing by livestock - have led to a rapid spread of woody shrubs across semi-arid Australia, a new study shows. Re-introduction of small mammals to desert areas could help prevent further invasion by the woody weeds, the researchers suggest. A dingo in semi-arid Australia. Extermination of dingoes The study in outback NSW compared conditions and consequent loss of small mammals have led to a on either side of the dingo fence - a two-metre tall, rapid spread of woody shrubs across semi-arid Australia. 5600-kilometre long fence erected more than a Credit: Ben Moore century ago to keep dingoes out of eastern Australia. Dingoes are common on the western side of the They assessed four sites in the Strzelecki Desert, fence, but rare on the other side, due to intensive two on either side of the dingo fence. The results control measures including poisoning, trapping and are published in the Journal of Animal Ecology. -

Control and Conservation of Abundant Kangaroo Species

animals Review The Perils of Being Populous: Control and Conservation of Abundant Kangaroo Species David Benjamin Croft 1,* and Ingrid Witte 2 1 School of Biological Earth & Environmental Sciences, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia 2 Rooseach@RootourismTM, Adelaide River, NT 0846, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: Kangaroos likely prospered for most of the last 65,000 years under the landscape management of Australia’s first people. From the arrival of British colonists in 1788, European agricultural practices, crops and livestock transformed the landscape to one less favourable to indigenous flora and fauna. However, the six species of large kangaroos persisted and came into conflict with cropping and pastoral enterprises, leading to controls on their abundance. After mass killing for bounties, a commercial industry emerged in the 1970s to sell meat and hides into domestic and international markets. The further intention was to constrain kangaroo abundance while sustaining kangaroos in the landscape. Human–human conflict has emerged about the necessity and means of this lethal control. Further control of the abundance of four of the six species is promoted. Their abundance is considered by some as a threat to biodiversity in conservation reserves, removing these as a haven. We therefore propose returning the kangaroos’ stewardship to the current and future generations of Aboriginal Australians. We envisage that a marriage of localised consumptive (bush tucker) and non-consumptive (wildlife tourism) uses in the indigenous-protected-area estate can better sustain abundant kangaroo populations into the future. Citation: Croft, D.B.; Witte, I. The Abstract: Australia’s first people managed landscapes for kangaroo species as important elements Perils of Being Populous: Control and of their diet, accoutrements and ceremony. -

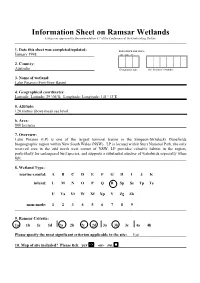

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Categories Approved by Recommendation 4.7 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties. 1. Date this sheet was completed/updated: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. January 1998 DD MM YY 2. Country: Australia Designation date Site Reference Number 3. Name of wetland: Lake Pinaroo (Fort Grey Basin) 4. Geographical coordinates: Latitude: Latitude: 29º06’S; Longitude: Longitude: 141º13’E 5. Altitude: 120 metres above mean sea level. 6. Area: 800 hectares 7. Overview: Lake Pinaroo (LP) is one of the largest terminal basins in the Simpson-Strzelecki Dunefields biogeographic region within New South Wales (NSW). LP is located within Sturt National Park, the only reserved area in the arid north west corner of NSW. LP provides valuable habitat in the region, particularly for endangered bird species, and supports a substantial number of waterbirds especially when full. 8. Wetland Type: marine-coastal: A B C D E F G H I J K inland: L M N O P Q R Sp Ss Tp Ts U Va Vt W Xf Xp Y Zg Zk man-made: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 9. Ramsar Criteria: 1a 1b 1c 1d 2a 2b 2c 2d 3a 3b 3c 4a 4b Please specify the most significant criterion applicable to the site: 1(a) 10. Map of site included? Please tick yes ⌧ -or- no. 11. Name and address of the compiler of this form: NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Conservation Assessment and Planning Division PO BOX 1967 Hurstville NSW 2220 Phone: 02 9585 6477 AUSTRALIA Fax: 02 9585 6495 12. -

Shrub Encroachment Is Linked to Extirpation of an Apex Predator

Journal of Animal Ecology 2017 doi: 10.1111/1365-2656.12607 Shrub encroachment is linked to extirpation of an apex predator Christopher E. Gordon*,1,2,3, David J. Eldridge4, William J. Ripple5, Mathew S. Crowther6, Ben D. Moore1 and Mike Letnic2,4 1Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment, Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW 2751, Australia; 2Centre for Ecosystem Science, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia; 3Centre for Environmental Risk Management of Bushfires, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW 2522, Australia; 4School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia; 5Global Trophic Cascades Program, Forest Ecosystems and Society, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA; and 6School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia Abstract 1. The abundance of shrubs has increased throughout Earth’s arid lands. This ‘shrub encroachment’ has been linked to livestock grazing, fire-suppression and elevated atmospheric CO2 concentrations facilitating shrub recruitment. Apex predators initiate trophic cascades which can influence the abundance of many species across multiple trophic levels within ecosystems. Extirpation of apex predators is linked inextricably to pastoralism, but has not been considered as a factor contributing to shrub encroachment. 2. Here, we ask if trophic cascades triggered by the extirpation of Australia’s largest terres- trial predator, the dingo (Canis dingo), could be a driver of shrub encroachment in the Strz- elecki Desert, Australia. 3. We use aerial photographs spanning a 51-year period to compare shrub cover between areas where dingoes are historically rare and common. We then quantify contemporary pat- terns of shrub, shrub seedling and mammal abundances, and use structural equation modelling to compare competing trophic cascade hypotheses to explain how dingoes could influence shrub recruitment. -

How Dingoes Sculpt the Shape of Sand Dunes in the Australian Desert 4 July 2018, by Ivy Shih

How dingoes sculpt the shape of sand dunes in the Australian desert 4 July 2018, by Ivy Shih suffered, and native vegetation cover increased in their absence. The increased vegetation also altered the patterns of wind flow and sand movement and how the sand settled on the sand dunes. Increased vegetation cover locked down the sand and sediment and allowed the wind to 'flow' over the top, creating taller dune peaks. In contrast, on the South Australia and Queensland side of the fence where dingoes were still present, the sand dunes were generally 'flatter' and not as tall. A dingo in the Strzelecki Desert. Credit: Peter Contos A new study by UNSW scientists has shown how the presence – and absence – of dingoes affects the desert landscape. Removing predators from an ecosystem can have a domino effect that impacts the geography of the environment and even the pattern of wind and sand movement, a new study by UNSW scientists has shown. Aerial photo of the dingo-proof fence in the Strzelecki In the Strzelecki Desert in north-west New South Desert. On the left of the Dingo Fence where there is a Wales, the Dingo Fence is a man-made barrier that low dingo population you can see higher shrub density. has been in the landscape for over a century. The This is compared to areas of high dingo population (right) Dingo Fence was built in the 1800s to keep where there is a low to medium shrub density. Credit: dingoes away from private land and livestock. On Mitchell Lyons the NSW side of the Dingo Fence is Sturt National Park, but dingo culling still occurs, as the animals are considered a pest to livestock producers. -

Soil Conservation Board District Plan : Northern Flinders Ranges

Soil Conservation Board District Plan Revised 2004 NORTHERNNORTHERN FLINDERSFLINDERS RANGESRANGES FOREWORD The Northern Flinders Soil Conservation Board has been involved in various activities since the inception of our first District Plan, which was completed in 1997. Most of the activities that we pursued since that time have been carried out or on-going. Several new projects have been completed, namely the Aroona Dam Biodiversity Enhancement Project. This project has seen the construction of two walking trails, interpretive signage, feral animal control including goats, foxes and cats, as well as a comprehensive destruction of rabbit warrens and land rehabilitation. Another project was a Pilot Programme, which involved local landholders, Animal Plant Control Commission and NPWSA in a range of activities including weed control, feral animal control and land rehabilitation. This integrated with the NPWSA Bounceback Programme in feral goat control, donkey control and 1080 baiting for foxes. Some projects undertaken by landholders were rabbit warren destruction, water point relocation, land rehabilitation and water ponding to name just a few. The Northern Flinders Soil Conservation Board has also become involved with a Regional Soil Board Executive, which has sourced funding from N.H.T. grants from the Commonwealth Government. Most of this funding is on a 50/50 basis and has met with approval from landholders throughout the Soil Board region. The proposed Natural Resources Management Act has yet to be legislated and further meetings are planned before it will become law. There are a number of concerns by Boards in the Rangelands of South Australia not the least of which is the ongoing funding of these proposed groups and the people who will drive them. -

Dog-Fence Proposal Reignites Debate Over Role of Dingoes

www.ecosmagazine.com Published: 2 July 2013 Dog-fence proposal reignites debate over role of dingoes Thomas Newsome Queensland’s Premier, Campbell Newman, recently announced funding for a feasibility study into resurrecting the wild dog fence in the state’s central west. The move comes in the wake of local farmers reporting dramatic stock losses – totalling $3 million dollars in annual revenue – from wild dog attacks. Credit: Thomas Newsome The outcome of the $30 000 feasibility study is predictable. Given the estimated cost of $8 million dollars to build, and assuming its long-term effectiveness, the 800 km fence’s economic viability would appear justified. But what goes largely unmentioned are the ecological consequences of creating a new barrier to wildlife movement. The dog-fence proposal also brings to a head the deceptively simple issue that is polarising Australian scientists working in the field: are dingoes ecologically good or bad? Other than humans, the dingo (Canis lupus dingo) is Australia’s largest mammalian predator. Fossil records indicate it has been present on the mainland for at least 4000 years. Certainly, Indigenous Australians killed dingoes, but it was the arrival of Europeans that marked the beginning of intensive dingo control and exclusion. Australia’s famous ‘dingo fence’ – at 5500 km, the world’s longest man-made structure – was erected to exclude dingoes from Australia’s prime grazing land in the south-east quarter of the continent. If the Queensland arm of the dog fence goes ahead, and if there is broad participation from all farmers in efforts to control wild dogs, dingoes will be excluded from vast tracts of land.