Reclaiming Our Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Restoration of the Right to Protest at Parliament

Law, Crime and History (2013) 1 LETTING DOWN THE DRAWBRIDGE: RESTORATION OF THE RIGHT TO PROTEST AT PARLIAMENT Kiron Reid1 Abstract This article analyses the history of the prohibition of protests around Parliament under the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005. This prohibited any demonstrations of one or more persons within one square kilometre of the Houses of Parliament unless permission had been obtained in writing from the police in advance. This measure both formed part of a pattern of the then Labour Government to restrict protest and increase police powers, and was symbolically important in restricting protest that was directed at politicians at a time when politicians have been very unpopular. The Government of Tony Blair had been embarrassed by a one-man protest by peace campaigner, Brian Haw. In response to sustained defiance, Mr. Blair’s successor as Labour Prime Minister, Gordon Brown, and opposition Conservative and Liberal Democrat MPs pledged to remove the restrictions, but this was not acted on by Parliament until September 2011. This article argues that the original restrictions were unnecessary, and that the much narrower successor provisions could be improved by being drafted more specifically. Keywords: protest, demonstration, protest at Parliament, freedom of speech, Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005, Brian Haw. Introduction This is about the sorry tale of sections 132-138 Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005 (SOCPA).2 These prohibited any demonstrations of one or more persons within one square kilometre of the Houses of Parliament unless advance written permission had been obtained from the Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis. -

Graduation 2014. Monday 21 July 2014 the University of Sheffield

Graduation 2014. Monday 21 July 2014 The University of Sheffield Your graduation day is a special day for you and your family, a day for celebrating your achievements and looking forward to a bright future. As a graduate of the University of Sheffield you have every reason to be proud. You are joining a long tradition of excellence stretching back more than 100 years. The University of Sheffield was founded with the amalgamation of the School of Medicine, Sheffield Technical School and Firth College. In 1905, we received a Royal Charter and Firth Court was officially opened by King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra. At that time, there were 363 students reading for degrees in arts, pure science, medicine and applied science. By the time of our centenary, there were over 25,000 students from more than 100 countries, across 70 academic departments. Today, a degree from Sheffield is recognised all over the world as a hallmark of academic excellence. We are proud of our graduates and we are confident that you will make a difference wherever you choose to build your future. With every generation of graduates, our university goes from strength to strength. This is the original fundraising poster from 1904/1905 which helped raise donations for the University of Sheffield. Over £50,000 (worth more than £15 million today) was donated by steelworkers, coal miners, factory workers and the people of Sheffield in penny donations to help found the University. A century on, the University is now rated as one of the top world universities – according to the Shanghai Jiao Tong Academic Ranking of World Universities. -

Sessional Orders and Resolutions

House of Commons Procedure Committee Sessional Orders and Resolutions Third Report of Session 2002–03 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 5 November 2003 HC 855 Published on 19 November 2003 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £11.00 The Procedure Committee The Procedure Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to consider the practice and procedure of the House in the conduct of public business, and to make recommendations. Current membership Sir Nicholas Winterton MP (Conservative, Macclesfield) (Chairman) Mr Peter Atkinson MP (Conservative, Hexham) Mr John Burnett MP (Liberal Democrat, Torridge and West Devon) David Hamilton MP (Labour, Midlothian) Mr Eric Illsley MP (Labour, Barnsley Central) Huw Irranca-Davies MP (Labour, Ogmore) Eric Joyce MP (Labour, Falkirk West) Mr Iain Luke MP (Labour, Dundee East) Rosemary McKenna MP (Labour, Cumbernauld and Kilsyth) Mr Tony McWalter MP (Labour, Hemel Hempstead) Sir Robert Smith MP (Liberal Democrat, West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine) Mr Desmond Swayne MP (Conservative, New Forest West) David Wright MP (Labour, Telford) Powers The powers of the committee are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 147. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at http://www.parliament.uk/parliamentary_ committees/procedure_committee.cfm. A list of Reports of the Committee in the present Parliament is at the back of this volume. -

Depleted Uranium P 4 We Talk a Lot About the Loyalty of These Daisaku Ikeda P 5 2 Pm Animals, and Their Willingness to Serve Gyosei Handa P 5 Us

ABOLISHABOLISH WARWAR Newsletter No: 9 Autumn 2007 Price per Issue £1 Remembrance Day - What will you be doing? Whether you wear red poppies, white poppies or both, whether you take part in a Remembrance service or The MAW AGM not, or you organise an event to question the fact of war, the day we Saturday 10th November remember those who have died in 11 am - 3 pm war is the day when MAW’s message should be loud and clear - war must Wesley’s Chapel 49 City Road end if we are not to add yet more London EC1Y 1AU names to our memorials. (nearest tube station Old Street) Animals in War Among the innocents we should Speaker: Craig Murray remember in November are the Craig is well known as the UK Ambassador to Uzbekistan who highlighted the human rights abuses he found there, millions of animals that took part in embarrassing the proponents of the ‘War on Terror’ with the and died for our political failures. result he is no longer in the Diplomatic Corps. He is a In 2004 a new monument appeared in fascinating, informative and funny speaker, with a wealth of London - the Animals in War experience to draw on. “Craig Murray has been a deep Memorial, inspired by Jilly Cooper’s embarrassment to the entire Foreign Office.” Jack Straw book of the same name. It ‘honours The AGM is open to all and is free. If you can get to the millions of conscripted animals London, then get to the AGM. And bring your friends. -

Mark Wallinger: State Britain: Tate Britain, London, 15 January – 27 August 2007

Mark Wallinger: State Britain: Tate Britain, London, 15 January – 27 August 2007 Yesterday an extraordinary work of political-conceptual-appropriation-installation art went on view at Tate Britain. There’ll be those who say it isn’t art – and this time they may even have a point. It’s a punch in the face, and a bunch of questions. I’m not sure if I, or the Tate, or the artist, know entirely what the work is up to. But a chronology will help. June 2001: Brian Haw, a former merchant seaman and cabinet-maker, begins his pavement vigil in Parliament Square. Initially in opposition to sanctions on Iraq, the focus of his protest shifts to the “war on terror” and then the Iraq war. Its emphasis is on the killing of children. Over the next five years, his line of placards – with many additions from the public - becomes an installation 40 metres long. April 2005: Parliament passes the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act. Section 132 removes the right to unauthorised demonstration within one kilometre of Parliament Square. This embraces Whitehall, Westminster Abbey, the Home Office, New Scotland Yard and the London Eye (though Trafalgar Square is exempted). As it happens, the perimeter of the exclusion zone passes cleanly through both Buckingham Palace and Tate Britain. May 2006: The Metropolitan Police serve notice on Brian Haw to remove his display. The artist Mark Wallinger, best known for Ecce Homo (a statue of Jesus placed on the empty fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square), is invited by Tate Britain to propose an exhibition for its long central gallery. -

FBU Firefighter Magazine • October/November 2916

THE MAGAZINE OF THE FIRE BRIGADES UNION | WWW.FBU.ORG.UK OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2016 SAFETY FOR SALE TIMES HAVE CHANGED THE RISKS HAVE NOT SEE P14 Plus FBU AT THE LABOUR PARTY CONFERENCE SEE P10 FIREFIGHTER FATALITIES: MORE THAN JUST GUIDANCE NEEDED SEE P12 GENERAL SECRETARY’S COMMENT MATT WRACK CUTS, AND THOSE WHO FORCE THEM THROUGH, MUST BE RESISTED During September our BOX/REPORTDIGITAL.CO.UK PAUL current state of affairs where members in Greater response times are increasing, Manchester were facing a putting lives at risk. bleak future. We have campaigned More than 1,250 relentlessly over the past six firefighters faced the sack – years, warning politicians only those who agreed to sign that the scale of cuts to the up to worse conditions of fire and rescue service is service would be re-engaged. such that public safety is Greater Manchester seriously compromised. Fire and Rescue Service We now have fire authority has to find savings of more Rapid response – but continuing cuts will take effect members also publicly than £14m, but this is no expressing this fear, as the justification for threatening negotiating process was of mental ill health than the link between an increased such action. stopped, but our officials in rest of the population. response time and rising fire FBU officials mounted Greater Manchester are well We are proud that our deaths is inextricably linked. a vigorous campaign that aware that further battles lottery will see a higher But this government attracted a lot of public and lie ahead. They will get our percentage of the monies remains deaf to the political support. -

English Is a Welsh Language

ENGLISH IS A WELSH LANGUAGE Television’s crisis in Wales Edited by Geraint Talfan Davies Published in Wales by the Institute of Welsh Affairs. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means without the prior permission of the publishers. © Institute of Welsh Affairs, 2009 ISBN: 978 1 904773 42 9 English is a Welsh language Television’s crisis in Wales Edited by Geraint Talfan Davies The Institute of Welsh Affairs exists to promote quality research and informed debate affecting the cultural, social, political and economic well-being of Wales. IWA is an independent organisation owing no allegiance to any political or economic interest group. Our only interest is in seeing Wales flourish as a country in which to work and live. We are funded by a range of organisations and individuals. For more information about the Institute, its publications, and how to join, either as an individual or corporate supporter, contact: IWA - Institute of Welsh Affairs 4 Cathedral Road Cardiff CF11 9LJ tel 029 2066 0820 fax 029 2023 3741 email [email protected] web www.iwa.org.uk Contents 1 Preface 4 1/ English is a Welsh language, Geraint Talfan Davies 22 2/ Inventing Wales, Patrick Hannan 30 3/ The long goodbye, Kevin Williams 36 4/ Normal service, Dai Smith 44 5/ Small screen, big screen, Peter Edwards 50 6/ The drama of belonging, Catrin Clarke 54 7/ Convergent realities, John Geraint 62 8/ Standing up among the cogwheels, Colin Thomas 68 9/ Once upon a time, Trevor -

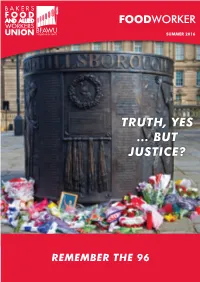

Truth, Yes … but Justice?

SUMMER 2016 TRUTH, YES … BUT JUSTICE? REMEMBER THE 96 2 FOODWORKER EDITOR’S SUMMER 2016 NOTES TRUTH, YES "… Jeremy Corbyn is … BUT the leader, get over JUSTICE? it and unite for the benefit of those you purport to represent" REMEMBER THE 96 "Ronnie Draper @ronniebfawu INSIDE THIS ISSUE: As we approach Annual Conference, We don’t want a return to the disloyalty of Editor’s Notes . 2 which will be held in Southport, the time to 1981 when the gang of four Roy Jenkins, reflect on where the political landscape has David Owen, Shirley Williams and Bill National President . 3 moved over the last year is upon us. If we Rogers left the party to form the SDP Dennis Nash presentation . .4 are honest the only significant political although if that is the only way that we are FastFood Day of Action . .5 change has been the landslide election of going to rid our party of the treachery that Jeremy Corbyn as Labour Party leader and appears to abound then so be it. Trade Union Bill . 6 the massive increase in the number of Who is the common enemy? Thank You Pauls! . 6 grassroots members who have joined in the Working people and the disadvantaged in our Womens' TUC Conference . .7 hope that we will see a move to a more society are under constant attack from the socialist agenda. most heinous government in living memory. Signature Flatbreads . .8 Labour = Loyalty? We and all those that we elected to Poverty Wages make us Ill! . 8 Since that day we have seen a number of parliament should be concentrating all our efforts on defeating the common enemy We are Wakefield . -

A Human Rights Approach to Policing Protest

House of Lords House of Commons Joint Committee on Human Rights Demonstrating respect for rights? A human rights approach to policing protest Seventh Report of Session 2008–09 Volume I Report, together with formal minutes and written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 3 March 2009 Ordered by the House of Lords to be printed 3 March 2009 HL Paper 47-I HC 320-I Published on 23 March 2009 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 Joint Committee on Human Rights The Joint Committee on Human Rights is appointed by the House of Lords and the House of Commons to consider matters relating to human rights in the United Kingdom (but excluding consideration of individual cases); proposals for remedial orders, draft remedial orders and remedial orders. The Joint Committee has a maximum of six Members appointed by each House, of whom the quorum for any formal proceedings is two from each House. Current membership HOUSE OF LORDS HOUSE OF COMMONS Lord Bowness John Austin MP (Labour, Erith & Thamesmead) Lord Dubs Mr Andrew Dismore MP (Labour, Hendon) (Chairman) Lord Lester of Herne Hill Dr Evan Harris MP (Liberal Democrat, Oxford West & Lord Morris of Handsworth OJ Abingdon) The Earl of Onslow Mr Virendra Sharma MP (Labour, Ealing, Southall) Baroness Prashar Mr Richard Shepherd MP (Conservative, Aldridge-Brownhills) Mr Edward Timpson MP (Conservative, Crewe & Nantwitch) Powers The Committee has the power to require the submission of written evidence and documents, to examine witnesses, to meet at any time (except when Parliament is prorogued or dissolved), to adjourn from place to place, to appoint specialist advisers, and to make Reports to both Houses. -

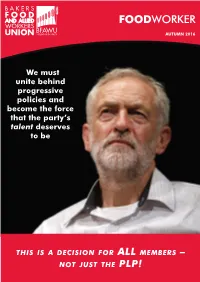

We Must Unite Behind Progressive Policies and Become the Force That the Party’S Talent Deserves to Be

AUTUMN 2016 We must unite behind progressive policies and become the force that the party’s talent deserves to be THIS IS A DECISION FOR ALL MEMBERS – NOT JUST THE PLP! 2 FOODWORKER EDITOR’S AUTUMN 2016 We must we NOTES unite behind progressive policies and become the force that the party’s "Hammering terms talent deserves to be and conditions is not the way to get a productive, proactive workforce" THIS IS A DECISION FOR ALL MEMBERS – NOT JUST THE PLP! "Ronnie Draper @ronniebfawu INSIDE THIS ISSUE: If anyone was ever in doubt about the from Eastern Europe for the dramatic Editor’s Notes . 2 negative effect a Tory government would reduction in wage levels, housing shortages have on those at the bottom of the wage and lengthening waiting times within the National President . 3 pile, you need look no further than the so NHS. Again this is massively wide of the Kumaran Bose . 5 called 'living wage', brought in by former mark. Migrant labour does not reduce Conference Report . 6 Chancellor, George Osborne. wage rates but opportunist employers do, After years which have seen pay freezes, employers who exploit financial situations Bill Morris' Conference Diary .10 the bedroom tax, cuts to in-work benefits, abroad to create a myth that is propagated by the right wing press. HEALTH & SAFETY hikes in VAT and the repeal of protective legislation, we now have a joke living wage We are the 5th richest economy in the National Safety that has been a green light for unscrupulous world run by a government who create Committee Update . -

BBC Trust Unit 180 Great Portland Street London W1W 5QZ

Editorial Standards Findings Appeals to the Trust and other editorial issues considered by the Editorial Standards Committee September 2010 issued October 2010 Getting the best out of the BBC for licence fee payers Editorial Standards Findings/Appeals to the Trust and other editorial issues considered byContents the Editorial Standards Committee Remit of the Editorial Standards Committee 1 Summary of findings 3 Findings 8 Newsnight, BBC Two, 19 January 2010 8 Newsnight, BBC Two, 19 January 2010 20 The World at One, BBC Radio 4, 8 December 2009 38 To Let, BBC Two, 20 December 2009 – Complaints Handling 44 The Culture Show, BBC Two, 4 February 2010 49 Rejected appeals 65 Fly Me To The Reverend Moon, BBC Radio 4, 19 April 2010 65 To Let, BBC Two, 29 December 2009 68 The Big Questions, BBC One (General complaint – bias against Muslims) 70 The Review Show, BBC Two, 26 February 2010 72 Scapegoat, BBC Northern Ireland, 26 October 2009 74 BBC News website reporting on Gaza conflict (2009) 77 Today, BBC Radio 4, 27 January 2010 80 Systemic bias on climate change 82 September 2010 issued October 2010 Editorial Standards Findings/Appeals to the Trust and other editorial issues considered by the Editorial Standards Committee Remit of the Editorial Standards Committee The Editorial Standards Committee (ESC) is responsible for assisting the Trust in securing editorial standards. It has a number of responsibilities, set out in its Terms of Reference at bbc.co.uk/bbctrust/about/meetings_and_minutes/bbc_trust_committees.html. The Committee comprises six Trustees: Richard Tait (Chairman), Chitra Bharucha, Mehmuda Mian, David Liddiment, Alison Hastings and Anthony Fry. -

As Used on the Famous Nelson Mandela: Underground Adventures in the Arms and Torture Trade Pdf

FREE AS USED ON THE FAMOUS NELSON MANDELA: UNDERGROUND ADVENTURES IN THE ARMS AND TORTURE TRADE PDF Mark Thomas | 352 pages | 28 Sep 2007 | Ebury Publishing | 9780091909222 | English | London, United Kingdom As Used On the Famous Nelson Mandela by Mark Thomas - Penguin Books Australia Mark Clifford Thomas born 11 April is an English comedianpresenter, political satirist and journalist from south London. Thomas describes himself as a " libertarian anarchist ". Mark Thomas was born in South London. His mother was a midwife and his father a self-employed builder and ex- lay preacher. He then won a scholarship to attend the independent Christ's Hospital School, where he attained O-levels and A-levels in English, history, and politics and economics. During his time at Bretton Hall, he made his debut as a performer, co-writing and performing satirical sketches at Wakefield Labour Club. After graduating, Thomas subsequently embarked on his comedy career, initially supporting himself through working on building sites with his father. Thomas' early exposure to comedy was through watching and listening to Dave AllenSteptoe and SonThe Goon Show and Tony As Used on the Famous Nelson Mandela: Underground Adventures in the Arms and Torture Trade ; his biggest influence was hearing a recording of Alexei Sayle : "It was like someone had kicked the door in - just As Used on the Famous Nelson Mandela: Underground Adventures in the Arms and Torture Trade to that tape and thinking that As Used on the Famous Nelson Mandela: Underground Adventures in the Arms and Torture Trade could do this stuff". Prior to his most renowned vehicle, The Mark Thomas Comedy ProductThomas was a frequent guest comic on the BBC Radio 1 show The Mary Whitehouse Experiencewhere he would do a routine about a specific topic of the week and involve studio audience members in the discussions.