DAVIDSCOTI Relations Between the Scottish Office and Local Authorities Have Gradually Deteriorated Since George Younger Declared

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OPEN CHANNELS Public Dialogue in Science and Technology

Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology OPEN CHANNELS Public dialogue in science and technology Report No. 153 March 2001 MEMBERS OF THE BOARD OF THE PARLIAMENTARY OFFICE OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY MARCH 2001 OFFICERS CHAIRMAN: Dr Ian Gibson MP VICE-CHAIRMAN: Lord Flowers FRS DIRECTOR: Professor David Cope PARLIAMENTARY MEMBERS House of Lords The Earl of Erroll Lord Oxburgh, KBE, PhD, FRS Professor the Lord Winston House of Commons Mr Richard Allan MP Mrs Anne Campbell MP Dr Michael Clark MP Mr Michael Connarty MP Mr Paul Flynn MP Dr Ashok Kumar MP Mrs Caroline Spelman MP Dr Phyllis Starkey MP Mr Ian Taylor, MBE, MP NON PARLIAMENTARY MEMBERS Professor Sir Tom Blundell, FRS Professor Jim Norton, FIEE, FRSA Sir David Davies, CBE, FREng, FRS Dr Frances Balkwill EX-OFFICIO MEMBERS Clerk of the House: represented by Mr Malcolm Jack Librarian of the House of Commons: represented by Mr Christopher Barclay Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology OPEN CHANNELS Public dialogue in science and technology Report No. 153 April 2001 Primary Author: Gary Kass POST would like to thank the following organisations and individuals for their information and comment @Bristol Agriculture an Environment Biotechnology Commission Association of British Healthcare Industries Association of Independent Research and Technology Organisations British Association for the Advancement of Science British Council British Energy Cabinet Office Centre for the Study of Environmental Change, University Confederation of British Industry of Lancaster Construction -

Political Party Funding

1071 Party Funding.qxd 30/11/04 11:32 Page a3 December 2004 The funding of political parties Report and recommendations 1071 Party Funding.qxd 30/11/04 11:32 Page a4 Translations and other formats For information on obtaining this publication in another language or in a large-print or Braille version please contact The Electoral Commission: Tel: 020 7271 0500 Email: [email protected] The Electoral Commission We are an independent body that was set up by the UK Parliament. We aim to gain public confidence and encourage people to take part in the democratic process within the UK by modernising the electoral process, promoting public awareness of electoral matters and regulating political parties. The funding of political parties Report and recommendations Copyright © The Electoral Commission 2004 ISBN: 1-904363-54-7 1071 Party Funding.qxd 30/11/04 11:32 Page 1 1 Contents Executive summary 3 Financial implications of limiting donations 84 Commission position 86 1Introduction 7 Political parties 7 6Public funding of political parties 89 Review process 9 Background 89 Priorities 10 Direct public funding 90 Scope 10 Indirect public funding 92 Stakeholders’ views 94 2 Attitudes towards the funding of Commission position 97 political parties 13 Reforming the policy development Research 13 grant scheme 97 Public opinion 14 New forms of public funding 98 Party activists 20 Attitudes towards implementation 23 7 The way forward 103 The importance of political parties 103 3Party income and expenditure 25 The way forward 104 The -

Mining Delegation Report Final1

Mining and Development in Peru With Special Reference to The Rio Blanco Project, Piura www.perusupportgroup.org.uk A Delegation Report Professor Anthony Bebbington, Ph.D. Michael Connarty, M.P. Wendy Coxshall, Ph.D. Hugh O’Shaughnessy Professor Mark Williams, Ph.D. Published by the Peru Support Group, March 2007 Mining and Development in Peru Contents List of Boxes, Figures and Tables Abbreviations Executive Summary Monterrico Metals: Responding to this report PART I: RIO BLANCO IN CONTEXT Chapter 1 Introduction Chapter 2 Mining, development, democracy and the environment in Peru Chapter 3 Mining and development in Piura Chapter 4 Majaz: background information on the case and this Delegation Chapter 5 Method and process of the Delegation Chapter 6 Events and changes since April 2006 PART II: ASSESSING THE RIO BLANCO CONFLICT Chapter 7 Assessing the debate on March 21st, 2006 Chapter 8 The Rio Blanco Project and development in Piura Chapter 9 The Rio Blanco Project and the environment Chapter 10 Wider issues embodied in the Rio Blanco case: governing mining for development, democracy and environmental security Chapter 11 Conclusions and ways forward PART III: ANNEXES Annex 1 Bibliography Annex 2 Detailed suggestions on environmental monitoring options Annex 3 On the importance of continued multi-stakeholder dialogue over the life of a natural resource extraction project Annex 4 Team Member Bio sketches Annex 5 Persons and organisations consulted ii Mining & Development in Peru List of boxes, figures and tables Box 1: Mining, acid mine drainage -

Fact Sheet Msps Mps and Meps: Session 4 11 May 2012 Msps: Current Series

The Scottish Parliament and Scottish Parliament I nfor mation C entre l ogo Scottish Parliament Fact sheet MSPs MPs and MEPs: Session 4 11 May 2012 MSPs: Current Series This Fact Sheet provides a list of current Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs), Members of Parliament (MPs) and Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) arranged alphabetically by the constituency or region that they represent. Abbreviations used: Scottish Parliament and European Parliament Con Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Green Scottish Green Party Ind Independent Lab Scottish Labour Party LD Scottish Liberal Democrats NPA No Party Affiliation SNP Scottish National Party UK Parliament Con Conservative and Unionist Party Co-op Co-operative Party Lab Labour Party LD Liberal Democrats NPA No Party Affiliation SNP Scottish National Party Scottish Parliament and Westminster constituencies do not cover the same areas, although the names of the constituencies may be the same or similar. At the May 2005 general election, the number of Westminster constituencies was reduced from 72 to 59, which led to changes in constituency boundaries. Details of these changes can be found on the Boundary Commission’s website at www.statistics.gov.uk/geography/westminster Scottish Parliament Constituencies Constituency MSP Party Aberdeen Central Kevin Stewart SNP Aberdeen Donside Brian Adam SNP Aberdeen South and North Maureen Watt SNP Kincardine Aberdeenshire East Alex Salmond SNP Aberdeenshire West Dennis Robertson SNP Airdrie and Shotts Alex Neil SNP Almond Valley Angela -

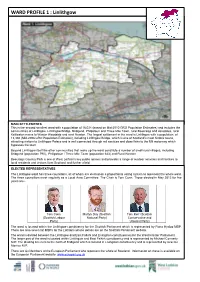

WARD PROFILE 1 : Linlithgow

WARD PROFILE 1 : Linlithgow MAIN SETTLEMENTS This is the second smallest ward with a population of 16,034 (based on Mid-2010 GRO Population Estimates) and includes the communities of Linlithgow, Linlithgow Bridge, Bridgend, Philpstoun and Three Mile Town, rural Beecraigs and Acredales, rural Kettleston mains to Wester Woodside and rural Newton. The largest settlement in the ward is Linlithgow with a population: of 13,360 (Mid-2008 GRO Population Estimates), including Linlithgow Bridge, which is one of Scotland’s most historic towns, attracting visitors to Linlithgow Palace and is well connected through rail services and close links to the M9 motorway which bypasses the town. Beyond Linlithgow itself the other communities that make up the ward constitute a number of small rural villages, including Bridgend (population 790), Philipstoun / Three Mile Town (population 643) and Rural Newton. Beecraigs Country Park is one of West Lothian’s key public spaces and provides a range of outdoor activities and facilities to local residents and visitors form Scotland and further afield. ELECTED REPRESENTATIVES The Linlithgow ward has three councillors, all of whom are elected on a proportional voting system to represent the whole ward. The three councillors meet regularly as a Local Area Committee. The Chair is Tom Conn. Those elected in May 2012 for five years are:- Tom Conn Martyn Day (Scottish Tom Kerr (Scottish (Scottish Labour National Party) Conservative and Party) Unionist Party) The ward is located within the Linlithgow constituency for the Scottish Parliament which is represented by Fiona Hyslop MSP. There are also seven list MSPs for the Lothians whose details are on the Scottish Parliament website. -

Withdrawal from Enhanced Cooperation: the Committee's Evidence Session with Baroness Wilcox

House of Commons European Scrutiny Committee Withdrawal from enhanced cooperation: the Committee's evidence session with Baroness Wilcox Thirty–ninth Report of Session 2010– 12 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 19 July 2011 HC 1341 Published on 24 October 2011 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £6.50 The European Scrutiny Committee The European Scrutiny Committee is appointed under Standing Order No.143 to examine European Union documents and— a) to report its opinion on the legal and political importance of each such document and, where it considers appropriate, to report also on the reasons for its opinion and on any matters of principle, policy or law which may be affected; b) to make recommendations for the further consideration of any such document pursuant to Standing Order No. 119 (European Committees); and c) to consider any issue arising upon any such document or group of documents, or related matters. The expression “European Union document” covers — i) any proposal under the Community Treaties for legislation by the Council or the Council acting jointly with the European Parliament; ii) any document which is published for submission to the European Council, the Council or the European Central Bank; iii) any proposal for a common strategy, a joint action or a common position under Title V of the Treaty on European Union which is prepared for submission to the Council or to the European Council; iv) any proposal for a common position, framework decision, decision or a convention under Title VI of the Treaty on European Union which is prepared for submission to the Council; v) any document (not falling within (ii), (iii) or (iv) above) which is published by one Union institution for or with a view to submission to another Union institution and which does not relate exclusively to consideration of any proposal for legislation; vi) any other document relating to European Union matters deposited in the House by a Minister of the Crown. -

February 2003

Nations and Regions: The Dynamics of Devolution Quarterly Monitoring Programme Scotland Quarterly Report February 2003 The monitoring programme is jointly funded by the ESRC and the Leverhulme Trust 1 Introduction: James Mitchell 1. Executive: Barry Winetrobe 2. The Parliament: Mark Shephard 3. The Media: Philip Schlesinger 4. Public Attitudes: John Curtice 5. UK Intergovernmental relations: Alex Wright 6. Relations with Europe: Alex Wright 7. Relations with Local Government: Neil McGarvey 8. Finance: David Bell 9. Devolution disputes & litigation: Barry Winetrobe 10. Political Parties: James Mitchell 11. Public Policies: Barry Winetrobe 2 Introduction James Mitchell The fire strike claimed a Ministerial scalp during the last quarter and much anguish within the Scottish Executive especially creating tensions between Edinburgh and London. Richard Simpson, junior Justice Minister, was forced to stand down after he described the strikers as ‘fascist bastards’ in a private comment reported in the press. In a bizarre twist, Simpson acknowledged that he was the Minister accused of having made the comment but insisted that he had made no such comment. First Minister Jack McConnell Minister made it clear that the Minister had to resign. He was replaced by junior Social Justice Minister Hugh Henry who, in turn, was replaced by Des McNulty, Finance Committee convener. This event was only one manifestation of difficulties created by the dispute. Education Minister Cathy Jamieson was criticised for not being ‘on message’ but the relations between London and Edinburgh on the fire dispute and the crisis in the Scottish fishing industry proved a running sore during the quarter. Calls were made for the Scottish Executive to negotiate a separate pay agreement with the Fire Brigades Union. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Wednesday Volume 503 13 January 2010 No. 23 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Wednesday 13 January 2010 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2010 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Parliamentary Click-Use Licence, available online through the Office of Public Sector Information website at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/ Enquiries to the Office of Public Sector Information, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU; e-mail: [email protected] 669 13 JANUARY 2010 670 Michael Connarty (Linlithgow and East Falkirk) (Lab): House of Commons Will my right hon. Friend raise the question of psychological and psychiatric services in particular, because cases that Wednesday 13 January 2010 have come to me recently have highlighted serious deficiencies? Although I commend the work of Combat Stress in Hollybush House in the constituency of my The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock hon. Friend the Member for Ayr, Carrick and Cumnock (Sandra Osborne), it is a voluntary charitable organisation PRAYERS that is taking up much of the strain that is sadly not being taken up by the psychiatric services offered to our troops on their return from combat. [MR.SPEAKER in the Chair] Mr. Murphy: My hon. Friend is right to talk about the need for continuing support as people prepare to BUSINESS BEFORE QUESTIONS return from theatre and at the point at which they arrive. I had the great honour of meeting some of our LONDON LOCAL AUTHORITIES BILL [LORDS] (BY soldiers as they returned from theatre in Afghanistan ORDER) and they talked about the need for continued and Motion made, That the Bill be read a Second time. -

![European Union (Croatian Accession and Irish Protocol) Bill (HL Bill 59) and European Union (Approvals) Bill [HL] (HL Bill 57)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8781/european-union-croatian-accession-and-irish-protocol-bill-hl-bill-59-and-european-union-approvals-bill-hl-hl-bill-57-3278781.webp)

European Union (Croatian Accession and Irish Protocol) Bill (HL Bill 59) and European Union (Approvals) Bill [HL] (HL Bill 57)

Debate on 17 December: European Union (Croatian Accession and Irish Protocol) Bill (HL Bill 59) and European Union (Approvals) Bill [HL] (HL Bill 57) On 17 December the House is expected to consider the second readings of two Bills relating to the European Union: the European Union (Croatian Accession and Irish Protocol) Bill and the European Union (Approvals) Bill [HL]. The first part of this Note provides summaries of the debates held in the House of Commons on the European Union (Croatian Accession and Irish Protocol) Bill. The second part sets out the provisions in the European Union (Approval) Bill and provides further information about the draft decisions for which it seeks approval. Matthew Purvis 12 December 2012 LLN 2012/044 House of Lords Library Notes are compiled for the benefit of Members of the House of Lords and their personal staff, to provide impartial, politically balanced briefing on subjects likely to be of interest to Members of the Lords. Authors are available to discuss the contents of the Notes with the Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public. Any comments on Library Notes should be sent to the Head of Research Services, House of Lords Library, London SW1A 0PW or emailed to [email protected]. Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 2. European Union (Croatian Accession and Irish Protocol) Bill ...................................... 1 2.1 Commons Second Reading ................................................................................... 1 2.2 Commons Committee Stage .................................................................................. 5 2.2.1 Clause 1: Approval of Croatian Accession Treaty ............................................ 5 2.2.2 Clauses 2 and 3: Approval of the Irish Protocol .............................................. -

Debt Relief (Developing Countries) Bill: Committee Stage Report Bill 83 of 2009-10 (As Amended; Bill 17 As Introduced) RESEARCH PAPER 10/26 11 March 2010

Debt Relief (Developing Countries) Bill: Committee Stage Report Bill 83 of 2009-10 (as amended; Bill 17 as introduced) RESEARCH PAPER 10/26 11 March 2010 This is a Private Member’s Bill, introduced by Andrew Gwynne MP on 16 December 2009, and published on 19 February 2010. The Bill had its Second Reading on 26 February, and had its Committee Stage on 9 March; with Report Stage scheduled for 12 March. This is a report on the Committee Stage of the Bill. It complements Research Paper 10/17 on the Bill as presented and considered at Second Reading. The Bill seeks to limit the amount that can be recovered by any commercial creditor of a set of countries designated as having unsustainable external debts. It would apply to those countries eligible for the IMF/World Bank Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative. The legislation would restrict the activities of so-called ‘vulture funds’, which buy developing countries’ sovereign debt at discounted prices, then seek to recover its value in full through the courts. Successful claims would be limited to an internationally agreed level, and apply equally to all commercial creditors. Debts incurred after the Bill’s entry into force would be excluded. In Committee, a new ‘sunset clause’ was added. The proposed legislation would now expire after one year unless renewed for a further year or made permanent by order. Ian Townsend Recent Research Papers 10/16 Sustainable Communities Act 2007 (Amendment) Bill [Bill 21 of 2009-10] 24.02.10 10/17 Debt Relief (Developing Countries) Bill [Bill 17 of -

Living Former Members of the House of Commons

BRIEFING PAPER Number 05324, 7 January 2019 Living former Members Compiled by of the House of Sarah Priddy Commons Living former Members MPs are listed with any titles at the time they ceased to be an MP and the party they belonged to at the time. The list does not include MPs who now sit in the House of Lords. A list of members of the House of Lords who were Members of the House of Commons can be found on the Parliament website under House of Lords FAQs. Further information More detailed information on MPs who served between 1979 and 2010, including ministerial posts and party allegiance, covering their time in the UK Parliament and other legislatures, can be found in the Commons Library Briefing on Members 1979-2010. Association of Former Members of Parliament The PoliticsHome website has contact details for the Association of Former Members of Parliament. Parliament: facts and figures • Browse all briefings in the series This series of publications contains data on various subjects relating to Parliament and Government. Topics include legislation, MPs, select committees, debates, divisions and Parliamentary procedure. Feedback Any comments, corrections or suggestions for new lists should be sent to the Parliament and Constitution Centre. Suggestions for new lists welcomed. www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Living former Members of the House of Commons Note: Does not include MPs who are now sit in the House of Lords Name Full Title Party* List Name Mr -

Impact Assessment

IMPACT ASSESSMENT Region: Scotland Location Muiryhall Street, Coatbridge, ML5 3EZ. To withdraw from Muiryhall Street and relocate staff to other Original Proposal HMRC offices within reasonable daily travel. The intention is to withdraw from Muiryhall Street, relocating Decision staff to Queensway House, East Kilbride and Cotton House, Glasgow by spring 2009. Risk to customer service. Risks/Issues Travel times for some staff may exceed or be at the limit of reasonable daily travel if relocating to Cotton House or Queensway House. Enquiry Centre services will continue to be provided from Muiryhall Street or from an alternative location nearby. Mitigating Action Further examination of individual circumstances will be undertaken through one to one discussions between managers and staff. No staff will be required to relocate beyond reasonable daily travel. Issued by Workforce Change 29 February 2008 Impact Assessment: Muiryhall Street, Coatbridge IMPACT ASSESSMENT Contents 1 SUMMARY ................................................................................................................. 3 1.1. Background.................................................................................................. 3 1.2. Enquiry Centre Customers........................................................................... 3 1.3. Socio-Economic ........................................................................................... 3 1.4. Staff.............................................................................................................