Standardizing Color Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agfa D-Lab.1 Is the Solution You've Been Looking For

AG2_01_23125_dlab1Folder_gb# 01.09.2003 13:41 Uhr Seite 2 vaert AB nsgatan 18 Kista Stockholm +46 8 793-0100 +46 8 793-0123 www.agfa.se and vaert AG/SA hstr. 7 Dübendorf +41 1 823-7111 +41 1 823-7255 www.agfa.ch wan Co., Ltd. Sung Chiang Rd. The unique all-in-one talent. 04, Taiwan, R.O.C. +886 2516-8899 +886 2516-1041 www.agfanet.com.tw d-lab.1 poration llenger Road o change. ld Park, NJ 07660 +1 201 440-2500 +1 201 440-6703 www.agfaus.com Asean , RI, RP, SGP, TH, VN) vaert Ltd. Menara Merais, Jalan 19/3 etaling Jaya angor +603 7957-4200 +603 7957-4700 www.agfa.com Iberia vaert S.A. a, 392 Barcelona +34 93 476-7600 +34 93 476-7619 www.agfa.es Nola YV, Central , Caribbean) vaert de Venezuela S.A. Principal de la Castellana Centro Letonia G Bank, Piso 9 cíon La Castellana 305 Caracas la 1060-A +58 212 263-6344 +58 212 263-4386 www.agfa.com rica, Near/Middle East, sia) vaert AG 10 01 60 Leverkusen Information on design, product descriptions, and scope of delivery are subject t Printed in Germany. DB+ML 411 0903 GB / TBWA\ +49 214 30-1 +49 214 30-54012 www.agfa.com World Class Imaging Solutions AG2_01_23125_dlab1Folder_gb# 01.09.2003 13:41 Uhr Seite 3 Expect the best. You want to satisfy all your customers' photo imaging needs and maximise your profits at the same time. The Agfa d-lab.1 is the solution you've been looking for. -

Agfacolor-Kinofilme International

Gert Koshofer Agfacolor-Kinofilme international Eine Gewähr für die Vollständigkeit, insbesondere bei kürzeren Dokumentar- und Kulturfilmen nach 1945 sowie den Filmen aus den früheren Warschauer-Pakt-Staaten (außer DDR) kann nicht übernommen werden. Werbekurzfilme und Amateur-Schmalfilme sind grundsätzlich nicht enthalten. Dafür sei auf das Buch von Dirk Alt (siehe Quellen) verwiesen. Lediglich auf Agfacolor Positivfilm kopierte Filme, die auf anderen Filmmaterialien (insbesondere Eastman Color) aufgenommen wurden, bleiben unberücksichtigt. TABELLE 1: ALPHABETISCHE LISTE Zeichenerklärung: (L) = Leverkusener Fabrikation, (W) = Wolfener Nachkriegsfabrikation, ohne Klammer = Wolfener Fabrikation vor 1945 Die Jahreszahl gibt das Jahr der Fertigstellung bzw. Premiere an. Wenn keine besondere Angabe erfolgt, handelt es sich bei den Titeln um Spielfilme. Soweit fremdsprachige Filme in den deutschen Verleih kamen, wird der deutsche Titel zuerst genannt. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Titel Jahr Land Bemerkungen ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 2 x 2 ist manchmal 5 (Kettö x kettö neha 5) (W) 1955 Ungarn 6. Landesschießen 1943 Innsbruck. Wehrbereit – Allezeit! 1943 D Dokumentarfilm Der 8. Wochentag (L) 1957 Polen/BRD nur Farbinsert 100 Jahre Photographie – 50 Jahre Agfa 1939 D Dokumentarfilm mit Farbinsert, ursprünglich „100 Jahre Photo- graphie und die Agfa“ 1000 Sterne leuchten (L) 1959 BRD 1940 (Goebbels’ Kinder gratulieren 1940 -

Artworks Information.Pdf

Artworks The image is not nothing (Concrete Archives) Judy Watson. and education in their native language. Throughout the witness tree, 2018 the subsequent crisis and Yugoslav wars of the 1990s, On the next visit I made rubbings of some of the Serbian language came to be perceived as the language trees and ground on the memorial site using charcoal of the oppressor. Today it is largely abandoned by the and earth from the site. There is an indelible memory majority Albanian population. within this place which I wanted to convey within the The community's fraught relationship towards its works on canvas and back in my studio in Brisbane. recent history and the violence of language, resonates I overlaid these ground pieces with the maps of the with the wider questions of trauma, memory, identity, perpetrators journey to Myall Creek and the journey of breakdown, and loss. Sgt Denny Day to bring them to justice. Counter to common opinion, it is much easier to I took lengths of muslin and wound them around face the prospect of one’s own death than to imagine several of the trees. It felt like covering a deep wound the death of the symbolic universe articulated in within the psyche of the trees, a reparative gesture on language. And this is precisely what Collins’ film is my part. about – the irreducible corporeality and, consequently, Then Greg attached microphones to the trees, the finitude of language. If the viewers believe there listening to the sounds deep within them. is a message for them here it could be only a brutal It felt like covering a deep wound within the psyche one: not only your body but your language too will dry of the trees, a reparative gesture on my part to ashes and blow away. -

Agfa Range of Films

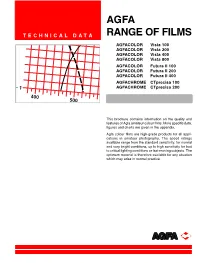

AGFA T E C H N I C A L D A T A RANGE OF FILMS AGFACOLOR Vista 100 AGFACOLOR Vista 200 AGFACOLOR Vista 400 AGFACOLOR Vista 800 AGFACOLOR Futura II 100 AGFACOLOR Futura II 200 AGFACOLOR Futura II 400 AGFACHROME CTprecisa 100 - 1 AGFACHROME CTprecisa 200 400 500 This brochure contains information on the quality and features of Agfa amateur colour films. More specific data, figures and charts are given in the appendix. Agfa colour films are high-grade products for all appli- cations in amateur photography. The speed ratings available range from the standard sensitivity, for normal and very bright conditions, up to high sensitivity for bad to critical lighting conditions or fast-moving subjects. The optimum material is therefore available for any situation which may arise in normal practice. 1 General comments Directions for use Agfacolor Vista & Futura II with Film speed EYE VISION technology Today’s ISO values are a combination of the former ASA and A film's colour rendition is governed by a number of factors. DIN values. The following table illustrates this point. The emulsions' spectral sensitivity or sensitisation is particularly ISO ASA DIN In comparison to ISO 100/21° important, when it comes to reproducing true-to-nature colours 100/21° 100 21° with the maximum accuracy. By means of the EYE VISION technology incorporated in all the Agfacolor Vista and Futura II 200/24° 200 24° twice as fast films, it is now possible to match, to a large extent, the films' 400/27° 400 27° four times as fast sensitisation to the colour perception of the human eye. -

Bulletin Online 12.2017

bulletin online 12.2017 “The Stars, the Silver Screen and the Qipao” costume exhibition at the Hong Kong Film Archive bulletin online 12.2017 Editorial In a few months, on 17 June 2018 to be precise, our Federation will turn 80 years old – a feat achieved by few other international associations in the cultural field. We are planning to celebrate this significant birthday in style with a number of initiatives throughout 2018. These will start on 1 January, with the release of a special FIAF anniversary logo. The setting up of exchanges between the first emerging film archives so soon after their formation in the mid-1930s was the result of the imme- diate realization by their leaders that establishing international contacts in order to share and exchange knowledge, practices, and collections was an absolute condition of their development, at a time when the preser- vation of film heritage was a completely new and unrecognized activity (yet a very expensive one). Within a couple of years they founded an inter- national network – FIAF – which over the last 80 years has cultivated the concept of “sharing” as its one of its raisons d’être. The topic chosen for the next FIAF symposium in Prague and the wealth of paper proposals re- ceived by the selection committee from colleagues in film archives around the world certainly confirm that sharing remains a key preoccupation in our global archiving community today. CONTENTS Indeed, many of FIAF’s initiatives and publications in 2017 have been all about sharing. To name but a few: the new resources -

Artist's Artwork Statements

Artworks The image is not nothing (Concrete Archives) Kumanara Boogar Australia needs to wake up. Walpa (Wind) Bulga (Big) Maralinga, 2008 I'm listening tonight. There are two things I can hear: water and profit. Kumanara Boogar made a number of works about Why are we selling water to make profit? That's Maralinga prior to their death. what I'm hearing. My people on the river, that relied on those animals Megan Cope for their food source for thousands of years, are now Mourning for Menindee 2020 dying. This is the second wave of genocide that's Mourning for Menindee comes as we continue to happening in my community. witness ongoing ecocide to one of the “Australia’s” So, I'm going to speak for my community. I'm going most important river systems, The Murray Darling to raise a voice for those that have been voiceless over Basin Authority continues to fail the nation and the the last 230 years. connecting Traditional Owners and custodians whom That's what frustrates me and that's what is have lived with and protected the river systems for frustrating our community. centuries. Why are our people dying young? Why are our Alarmed by the enormous fish kills which saw people suffering? hundreds of thousands of fresh water fish species Because of the greed. The taking of our water. suffocate to death from the blue-green algae blooms Where is First Nations rights to water? We have a along with the unrecorded deaths of Emu, Cope felt right to fresh water! compelled to make mourning ceremonial wreaths Put the water back in the river — not just for us — with cotton flowers and fish scales whilst listening but for the environment. -

Aerial Photography Product Overview 2004

Aerial Photography Aerial Photography Product Overview 2004 With their spectral sensitivity extending to the infrared range, © Air Flight Service Inc., 2220 Calle de Luna, Santa Clara, CA 95054, USA, tel. +1-408-988 0107, www.airphoto.com :Aviphot Pan black-and-white recording films register more details. :Aviphot Color and Chrome recording films are fine examples of technological sophistication. Their outstanding quality is characterised by high image definition and reproduction of the smallest details. Black-and-white > Camera Films Use Processing Features/Benefits :Aviphot Pan 80 PE1 Low to high altitude flights. Continuous tone processor or -Protection layer to prevent scratching. :Aviphot Pan 80 PE0 rewind development. -Excellent penetration through haze: sharp images. High resolution, intermediate Developer: G 74 c or - Clear differentiation of species in agricultural and ecological studies. speed, extremely fine grain G 74 c + AD 74. - Control of image contrast: the film can be processed as a low contrast film for large scale photography or as a panchromatic negative film. Fixer: G 333 c + :Aditan. high contrast film for other applications. Average gradient between 0.9 and 1.9. :Aviphot Pan 200 PE1 Low to medium altitude flights. Continuous tone processor or -Excellent penetration through haze: higher image contrast and therefore more information. :Aviphot Pan 200 PE0 rewind development. - No special recording filters required. Yellow filters can be used to get a higher image contrast. :Aviphot Pan 200 PE0-AR Developer: G 74 c or - Average gradient can vary between 0.8 and 1.6. Medium speed, fine grain G 74 c + AD 74. -Higher speed means shorter exposure times, smaller apertures (= higher sharpness over the entire image) and panchromatic negative film. -

Copyright by Christelle Georgette Le Faucheur 2012

Copyright by Christelle Georgette Le Faucheur 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Christelle Georgette Le Faucheur Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Defining Nazi Film: The Film Press and the German Cinematic Project, 1933-1945 Committee: David Crew, Supervisor Sabine Hake, Co-Supervisor Judith Coffin Joan Neuberger Janet Staiger Defining Nazi Film: The Film Press and the German Cinematic Project, 1933-1945 by Christelle Georgette Le Faucheur, Magister Artium Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Acknowledgements Though the writing of the dissertation is often a solitary endeavor, I could not have completed it without the support of a number of institutions and individuals. I am grateful to the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin, for its consistent support of my graduate studies. Years of Teaching Assistantships followed by Assistant Instructor positions have allowed me to remain financially afloat, a vital condition for the completion of any dissertation. Grants from the Dora Bonham Memorial Fund and the Centennial Graduate Student Support Fund enabled me to travel to conferences and present the preliminary results of my work, leading to fruitful discussions and great improvements. The Continuing Fellowship supported a year of dissertation writing. Without the help of Marilyn Lehman, Graduate Coordinator, most of this would not have been possible and I am grateful for her help. I must also thank the German Academic Exchange Service, DAAD, for granting me two extensive scholarships which allowed me to travel to Germany. -

Euromed 2020 2 November 2020

Vocabularies for Access to History and New Knowledge: Focus on the Getty Vocabularies Patricia Harpring Managing Editor Getty Vocabulary Program Getty Research Institute EuroMed 2020 2 November 2020 Find the Getty Vocabs Online • For information about the Getty vocabularies, see this site • Search the data, access data releases, how to contribute, editorial guidelines, training materials, news • Contact us: [email protected] Euromed 2020: Getty Vocabularies http://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies/index.html Patricia Harpring Getty Vocabularies 2 November 2020 1 My box of research materials for one project, many years ago The Way We Were Finding information by hand Discovery, Knowledge Creation, and Dissemination of research and art information: pillars of GRI mission • How did art historians do research in the past? • By hand, physical resources and card catalogs, bibliographic indexes such as BHA (Bibliography for the History of Art) • Printing out , photocopying, taking photos, note taking • Traveling around the world, many months to find all data • Needed better methods and tools for research and discovery • Solutions would also address needs of repositories, other Goal = data linked to other data, discoverable – cataloging institutions with mission to disseminate their data First = deal with human factor, links/consensus across • The Getty Vocabularies, CDWA, etc. were developed to allow different disciplines; repositories (archives, special consistency in cataloging and improvement of retrieval collections, visual resources, -

Set of Methodologies for Archive Film Digitization and Restoration With

SET OF METHODOLOGIES FOR ARCHIVE FILM DIGITIZATION AND RESTORATION WITH EXAMPLES OF THEIR APPLICATION IN ORWO REGION Karel Fliegel a, Stanislav Vítek a, Petr Páta a, Miloslav Novák b, Jiří Myslík b, Josef Pecák b, and Marek Jícha b a Czech Technical University in Prague, and b Film and TV School of Academy of Performing Arts in Prague, Czech Republic ABSTRACT PERCEIVED DIFFERENCES IN COLOR AND LIGHT TONALITY APPEARANCE I Set of verified methodologies for archive films’ restoration and digitization. I Assisting tool for measuring and monitoring the already digitized image sources. I Suitable especially for nonstandard laboratory or creative techniques in so-called ORWO region. I Displayed using a reference digital projector with split screen (DFRRP vs. DRA). I Umbrella of the techniques formed by Digitally Restored Authorizate (DRA) methodology. I Can be also used to assess the differences in respect to the analog film (RRP vs. DFRRP). I Aiming the appearance of the digitized film as close as possible to the original author’s concept. I Procedure based on CIEDE2000 color difference formula as a guidance to assess the impact of I Tools for objective assessment of perceived differences in the outcomes of the color grading process. perceived differences in color and light tonality in the projected images. I Techniques for evaluation of appearance match among various versions of the digitized film. FIGURE 4 INTRODUCTION AND PROBLEM DESCRIPTION Film projector The motivation comes from the need to establish methodologies and proper technical procedures to Image achieve high-quality digitization and restoration of the films produced in the very particular ORWO region. -

Center-40.Pdf

CENTER40 CENTER40 NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS Record of Activities and Research Reports June 2019 – May 2020 Washington, 2020 National Gallery of Art CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS Washington, DC Mailing address: 2000B South Club Drive, Landover, Maryland 20785 Telephone: (202) 842- 6480 E- mail: [email protected] Website: www.nga.gov/casva Copyright © 2020 Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law, and except by reviewers from the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Published by the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts at the National Gallery of Art ISSN 1557- 198X (print) ISSN 1557- 1998 (online) Publisher and Editor in Chief, Emiko K. Usui Series Editor, Peter M. Lukehart Center Report Coordinator, Jen Rokoski Managing Editor, Cynthia Ware Design Manager, Wendy Schleicher Typesetting and layout by BW&A Books, Inc. Printed on McCoy Silk by C&R Printing, Chantilly, Virginia Photography of CASVA fellows and events by the department of imaging and visual services, National Gallery of Art Frontispiece: Members and staff of the Center, December 2019 CONTENTS 6 Preface 7 Report on the Academic Year June 2019 – May 2020 8 Board of Advisors and Special Selection Committees 9 Staff 11 Report of the Dean 17 Members 28 Meetings 41 Lectures 44 Publications and Web Presentations 45 Research 55 Research -

German Film and Its Politics at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century Wayne State University Press, 2010 $39.95 (Paperback)

Alexandra H. Bush Book Review: Jaimey Fisher and Brad Prager, eds., The Collapse of the Conventional: German Film and its Politics at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century Wayne State University Press, 2010 $39.95 (paperback) The Collapse of the Conventional is a scholarly It has become nearly impossible to speak response to the popular and critical perception uncritically of “national” cinemas in film studies, of a “return” in German cinema since 2000. After and Fisher and Prager approach the topic with twenty years of movies intended more for national due caution. Taking a cue from Randall Halle’s entertainment than international prestige, excellent German Film After Germany, they adopt a German films of the last ten years have received discursive approach to the “nation” in the collection, renewed attention and respect from audiences, which includes studies on several transnational critics, and scholars alike.1 Jaimey Fisher and productions and works from German-speaking Brad Prager’s ambitious collection identifies re- nations outside Germany that nonetheless engage engagement with 20th century German history and with specifically German historical and political politics as the defining aspect of this new period discourses.5 Working from this critical concept and sets out to examine this engagement across a of the nation, The Collapse of the Conventional is broad selection of films. Their introduction offers loosely organized around three main themes: films a brief outline of German film history, identifying that revisit World War II,