Mumbai Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mumbai District

Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of Mumbai District MSME – Development Institute Ministry of MSME, Government of India, Kurla-Andheri Road, Saki Naka, MUMBAI – 400 072. Tel.: 022 – 28576090 / 3091/4305 Fax: 022 – 28578092 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.msmedimumbai.gov.in 1 Content Sl. Topic Page No. No. 1 General Characteristics of the District 3 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 3 1.2 Topography 4 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 5 1.4 Forest 5 1.5 Administrative set up 5 – 6 2 District at a glance: 6 – 7 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Areas in the District Mumbai 8 3 Industrial scenario of Mumbai 9 3.1 Industry at a Glance 9 3.2 Year wise trend of units registered 9 3.3 Details of existing Micro & Small Enterprises and artisan 10 units in the district. 3.4 Large Scale Industries/Public Sector undertaking. 10 3.5 Major Exportable item 10 3.6 Growth trend 10 3.7 Vendorisation /Ancillarisation of the Industry 11 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 11 3.8.1 List of the units in Mumbai district 11 3.9 Service Enterprises 11 3.9.2 Potentials areas for service industry 11 3.10 Potential for new MSME 12 – 13 4 Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprises 13 4.1 Details of Major Clusters 13 4.1.1 Manufacturing Sector 13 4.2 Details for Identified cluster 14 4.2.1 Name of the cluster : Leather Goods Cluster 14 5 General issues raised by industry association during the 14 course of meeting 6 Prospects of training programmes during 2012 – 13 15 7 Action plan for MSME Schemes during 2012 – 13. -

1. INTRODUCTION the Importance of River Can Be Traced Way Back Into

1. INTRODUCTION The importance of river can be traced way back into history. The nomadic Stone Age man always wandered around rivers. The world’s greatest civilizations have flourished on the banks of rivers. The Nile River was a key for the development of Ancient Egypt, the Indus River for the development of Mohenjo-Daro civilization, the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers for the development of Mesopotamian cultures, the Tiber River for Ancient Rome, etc. Ever since man learnt the benefits of rivers, he has used the river for various purposes like drinking, domestic use, irrigation, navigation, fishing, etc. As man advanced he invented new techniques to exploit river waters. With the advent of industrialization, the river water was now being used as a way to dispose of industrial waste, sewage and other domestic waste. Today, success of human civilization in developing or under developing countries mostly depends upon its industrial productivity that leads to economic progress of the country. Urbanization, globalization and industrialization all have an indirect or not specifically intended effect on ecosystem (Tanner et al., 2001). The disposal of human waste is another great challenge in both developed and developing countries (Zimmel et al. 2004).Waterways have been considered as convenient, cheapest and effective path for disposal of human waste. Aquatic ecosystems have been threatened worldwide by pollution and non unsustainable land use. Effect of poor quality of water on human health was noted first time in1854 by John Snow when he traced the outburst of cholera epidemic in London Thames River which was polluted to a great extent by sewage. -

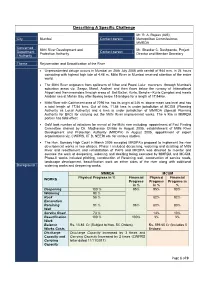

Describing a Specific Challenge

Describing A Specific Challenge Mr. R. A. Rajeev (IAS), City Mumbai Contact person Metropolitan Commissioner, MMRDA Concerned Mithi River Development and Mr. Shankar C. Deshpande, Project Department Contact person Protection Authority Director and Member Secretary / Authority Theme Rejuvenation and Beautification of the River • Unprecedented deluge occurs in Mumbai on 26th July 2005 with rainfall of 944 mm. in 24 hours coinciding with highest high tide of 4.48 m. Mithi River in Mumbai received attention of the entire world. • The Mithi River originates from spillovers of Vihar and Powai Lake traverses through Mumbai's suburban areas viz. Seepz, Marol, Andheri and then flows below the runway of International Airport and then meanders through areas of Bail Bazar, Kurla, Bandra - Kurla Complex and meets Arabian sea at Mahim Bay after flowing below 15 bridges for a length of 17.84Km. • Mithi River with Catchment area of 7295 ha. has its origin at 246 m. above mean sea level and has a total length of 17.84 kms. Out of this, 11.84 kms is under jurisdiction of MCGM (Planning Authority as Local Authority) and 6 kms is under jurisdiction of MMRDA (Special Planning Authority for BKC) for carrying out the Mithi River improvement works. The 6 Km in MMRDA portion has tidal effect. • GoM took number of initiatives for revival of the Mithi river including appointment of Fact Finding Committee chaired by Dr. Madhavrao Chitale in August 2005, establishment of Mithi River Development and Protection Authority (MRDPA) in August 2005, appointment of expert organisations viz. CWPRS, IIT B, NEERI etc. for various studies. -

Sighting Records of Greylag Goose (Anser Anser) from Maharashtra

Sighting records of Greylag Goose (Anser anser) from Maharashtra Raju Kasambe*, Dr. Anil Pimplapure**, Mr. Gopal Thosar*** & Dr. Manohar Khode# *G-1, Laxmi Apartments, 64, Vidya Vihar Colony, Pratap Nagar, Nagpur-440022, Maharashtra E-mail: [email protected], Phone: (0712-2241893) **Q-12, Siddhivinayak Apartments, Laxmi Nagar, Nagpur-440022, Maharashtra ***Honorary Wildlife Warden, 66, Ganesh Colony, Pratap Nagar, Nagpur-440022, Maharashtra #Shivaji Nagar, At. Warud, District Amravati, Maharashtra. Dr. Manohar Khode alongwith birder friend Mr. P. D. Lad had gone to birdwatching on 31st October 1993 at Pandhari reservoir near Warud in Amravati district of Maharashtra. They got a pleasant surprise when they saw a flock of large birds looking somewhat like domestic goose but grey-brown in colour. The size was as big as Barheaded Goose (Anser indicus) but they were different in colouration. On comparison with colour plates in the Pictorial Guide (1995) they identified the geese as Greylag Goose (Anser anser). Total 11 geese were sighted here. Thereafter a follow up was kept every year at the Pandhari reservoir in winter. However Greylag Goose was not sighted again. Probably this flock was vagrant. The Greylag Goose is large goose with overall gray colour, pink bill and pink legs. It is winter a visitor to the northern subcontinent. On 31st December 2006, the authors (RK, AP, GT) visited Shiregaon Bandh reservoir near Navegaon Bandh Sanctuary in Gondia district of Maharashtra. Again authors visited Shiregaon Bandh reservoir on 1st January 2007. From the roadside we could see few Greylag Goose at the far end of the reservoir. Then we visited the backside of the reservoir. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

Bombay High Court

2007 Bombay High Court 2007 JANUARY FEBRUARY MARCH APRIL S 7142128 S 4111825S 4111825S 1 8 15 22 29 M 1 8152229 M 51219 26 M 51219 26 M 2 9 16 23 30 T 2 9162330 T 6132027 T 6132027 T 3101724 W 3 10 17 24 31 W 7142128 W 7142128W 4111825 T 4 11 18 25 T 1 8 15 22 T 1 8 15 22 29 T 5121926 F 5 12 19 26 F 2916 23 F 2 9 16 23 30 F 6 13 20 27 S 61320 27 S 31017 24 S 3 10 17 24 31 S 7 14 21 28 1. Sundays, Second & Fourth Saturdays and other Holidays are shown in red. MAY 2. The Summer Vacation of the Court will commence on Monday the 7th May, JUNE S 6132027 2007 and the Court will resume its sitting on Monday the 4th June, 2007. S 3101724 3. The court will remain closed on account of October Vacation from 5th M 7142128 November to 18th November, 2007. M 4111825 T 1 8 15 22 29 4. Christmas Vacation from 24th December, 2007 to 6th January, 2008. T 5121926 5. Id-uz-Zuha, Muharram, Milad-un-Nabi, Id-ul-Fitr and Id-uz-Zuha W 2 9 16 23 30 respectively are subject to change depending upon the visibility of the W 6132027 T 3 10 17 24 31 Moon. If the Government of India declares any change in these dates through T 7142128 TV/AIR/Newspaper, the same will be followed. F 4 11 18 25 6. -

MEL Unclaimed Dividend Details 2010-2011 28.07.2011

MUKAND ENGINEERS LIMITED FINAL FOLIO DIV. AMT. NAME FATHERS NAME ADDRESS PIN CODE IEFP Trns. Date IN30102220572093 48.00 A BHASKER REDDY A ASWATHA REDDY H NO 1 1031 PARADESI REDDY STREET NR MARUTHI THIYOTOR PULIVENDULA CUDDAPAH 516390 03-Aug-2017 A000006 60.00 A GAFOOR M YUSUF BHAIJI M YUSUF 374 BAZAR STREET URAN 400702 03-Aug-2017 A001633 22.50 A JANAKIRAMAN G ANANTHARAMA KRISHNAN 111 H-2 BLOCK KIWAI NAGAR KANPUR 208011 03-Aug-2017 A002825 7.50 A K PATTANAIK A C PATTANAIK B-1/11 NABARD NAGAR THAKUR COMPLEX KANDIVLI E BOMBAY 400101 03-Aug-2017 A000012 12.00 A KALYANARAMAN M AGHORAM 91/2 L I G FLATS I AVENUE ASHOK NAGAR MADRAS 600083 03-Aug-2017 A002573 79.50 A KARIM AHMED PATEL AHMED PATEL 21 3RD FLR 30 NAKODA ST BOMBAY 400003 03-Aug-2017 A000021 7.50 A P SATHAYE P V SATHAYE 113/10A PRABHAT RD PUNE 411004 03-Aug-2017 A000026 12.00 A R MUKUNDA A G RANGAPPA C/O A G RANGAPPA CHICKJAJUR CHITRADURGA DIST 577523 03-Aug-2017 1201090001143767 150.00 A.R.RAJAN . A.S.RAMAMOORTHY 4/116 SUNDAR NAGARURAPULI(PO) PARAMAKUDI. RAMANATHAPURAM DIST. PARAMAKUDI. 623707 03-Aug-2017 A002638 22.50 ABBAS A PALITHANAWALA ASGER PALITHANAWALA 191 ABDUL REHMAN ST FATEHI HOUSE 5TH FLR BOMBAY 400003 03-Aug-2017 A000054 22.50 ABBASBHAI ADAMALI BHARMAL ADAMLI VALIJI NR GUMANSINHJI BLDG KRISHNAPARA RAJKOT GUJARAT 360001 03-Aug-2017 A000055 7.50 ABBASBHAI T VOHRA TAIYABBHAI VOHRA LOKHAND BAZAR PATAN NORTH GUJARAT 384265 03-Aug-2017 A006583 4.50 ABDUL AZIZ ABDUL KARIM ABDUL KARIM ECONOMIC INVESTMENTS R K SHOPPING CENTRE SHOP NO 6 S V ROAD SANTACRUZ W BOMBAY 400054 03-Aug-2017 A002095 60.00 ABDUL GAFOOR BHAIJI YUSUF 374 BAZAR ROAD URAN DIST RAIGAD 400702 03-Aug-2017 A000057 15.00 ABDUL HALIM QUERESHI ABDUL KARIM QUERESHI SHOP NO 1 & 2 NEW BBY SHOPPPING CET JUHU VILE PARLE DEVLOPEMENT SCHEME V M RD VILE PARLE WEST BOMBAY 400049 03-Aug-2017 IN30181110055648 15.00 ABDUL KAREEM K. -

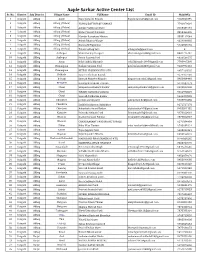

Aaple Sarkar Active Center List Sr

Aaple Sarkar Active Center List Sr. No. District Sub District Village Name VLEName Email ID MobileNo 1 Raigarh Alibag Akshi Sagar Jaywant Kawale [email protected] 9168823459 2 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) VISHAL DATTATREY GHARAT 7741079016 3 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Ashish Prabhakar Mane 8108389191 4 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Kishor Vasant Nalavade 8390444409 5 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Mandar Ramakant Mhatre 8888117044 6 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Ashok Dharma Warge 9226366635 7 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Karuna M Nigavekar 9922808182 8 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Tahasil Alibag Setu [email protected] 0 9 Raigarh Alibag Ambepur Shama Sanjay Dongare [email protected] 8087776107 10 Raigarh Alibag Ambepur Pranit Ramesh Patil 9823531575 11 Raigarh Alibag Awas Rohit Ashok Bhivande [email protected] 7798997398 12 Raigarh Alibag Bamangaon Rashmi Gajanan Patil [email protected] 9146992181 13 Raigarh Alibag Bamangaon NITESH VISHWANATH PATIL 9657260535 14 Raigarh Alibag Belkade Sanjeev Shrikant Kantak 9579327202 15 Raigarh Alibag Beloshi Santosh Namdev Nirgude [email protected] 8983604448 16 Raigarh Alibag BELOSHI KAILAS BALARAM ZAVARE 9272637673 17 Raigarh Alibag Chaul Sampada Sudhakar Pilankar [email protected] 9921552368 18 Raigarh Alibag Chaul VINANTI ANKUSH GHARAT 9011993519 19 Raigarh Alibag Chaul Santosh Nathuram Kaskar 9226375555 20 Raigarh Alibag Chendhre pritam umesh patil [email protected] 9665896465 21 Raigarh Alibag Chendhre Sudhir Krishnarao Babhulkar -

CRAMPED for ROOM Mumbai’S Land Woes

CRAMPED FOR ROOM Mumbai’s land woes A PICTURE OF CONGESTION I n T h i s I s s u e The Brabourne Stadium, and in the background the Ambassador About a City Hotel, seen from atop the Hilton 2 Towers at Nariman Point. The story of Mumbai, its journey from seven sparsely inhabited islands to a thriving urban metropolis home to 14 million people, traced over a thousand years. Land Reclamation – Modes & Methods 12 A description of the various reclamation techniques COVER PAGE currently in use. Land Mafia In the absence of open maidans 16 in which to play, gully cricket Why land in Mumbai is more expensive than anywhere SUMAN SAURABH seems to have become Mumbai’s in the world. favourite sport. The Way Out 20 Where Mumbai is headed, a pointer to the future. PHOTOGRAPHS BY ARTICLES AND DESIGN BY AKSHAY VIJ THE GATEWAY OF INDIA, AND IN THE BACKGROUND BOMBAY PORT. About a City THE STORY OF MUMBAI Seven islands. Septuplets - seven unborn babies, waddling in a womb. A womb that we know more ordinarily as the Arabian Sea. Tied by a thin vestige of earth and rock – an umbilical cord of sorts – to the motherland. A kind mother. A cruel mother. A mother that has indulged as much as it has denied. A mother that has typically left the identity of the father in doubt. Like a whore. To speak of fathers who have fought for the right to sire: with each new pretender has come a new name. The babies have juggled many monikers, reflected in the schizophrenia the city seems to suffer from. -

The High Court at Bombay (Extension of Jurisdiction to Goa, Daman and Diu) Act, 1981 Act No

THE HIGH COURT AT BOMBAY (EXTENSION OF JURISDICTION TO GOA, DAMAN AND DIU) ACT, 1981 ACT NO. 26 OF 1981 [9th September, 1981.] An Act to provide for the extension of the jurisdiction of the High Court at Bombay to the Union territory of Goa, Daman and Diu, for the establishment of a permanent bench of that High Court at Panaji and for matters connected therewith. BE it enacted by Parliament in the Thirty-second Year of the Republic of India as follows:— 1. Short title and commencement.—(1) This Act may be called the High Court at Bombay (Extension of Jurisdiction to Goa, Daman and Diu) Act, 1981. (2) It shall come into force on such date1 as the Central Government may, by notification in the Official Gazette, appoint. 2. Definitions.—In this Act, unless the context otherwise requires,— (a) “appointed day” means the date on which this Act comes into force; (b) “Court of the Judicial Commissioner” means the Court of the Judicial Commissioner for Goa, Daman and Diu. 3. Extension of jurisdiction of Bombay High Court to Goa, Daman and Diu.—(1) On and from the appointed day, the jurisdiction of the High Court at Bombay shall extend to the Union territory of Goa, Daman and Diu. (2) On and from the appointed day, the Court of the Judicial Commissioner shall cease to function and is hereby abolished: Provided that nothing in this sub-section shall prejudice or affect the continued operation of any notice served, injunction issued, direction given or proceedings taken before the appointed day by the Court of the Judicial Commissioner, abolished by this sub-section, under the powers then conferred upon that Court. -

Prefill Validate Clear

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the amount credited to Investor Education and Protection Fund. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-1 CIN/BCIN L92199MH1995PLC084610 Prefill Company/Bank Name HINDUJA GLOBAL SOLUTIONS LIMITED Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 309580.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Date of event (date of declaration of dividend/redemption date of preference shares/date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type maturity of Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred bonds/debentures/application money refundable/interest thereon (DD-MON-YYYY) V KARUNAKARAN VAITHY OLD NO 206 K NEW NO 261 K ADVAITHAINDIA ASARAM ROAD ALAGAPURAMTAMIL NADU NR ALL IN ONESALEM STORE SALEM 636004 IN303028-IN303028-55078777Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend40.00 31-JUL-2010 RACHNA GUPTA VIVEK GUPTA 21 GURU NANAK NAGAR NAINI ALLAHABADINDIA ALLAHABAD UTTAR PRADESH ALLAHABAD 211008 IN303116-IN303116-10049624Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend1000.00 31-JUL-2010 -

Mumbai-Marooned.Pdf

Glossary AAI Airports Authority of India IFEJ International Federation of ACS Additional Chief Secretary Environmental Journalists AGNI Action for good Governance and IITM Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology Networking in India ILS Instrument Landing System AIR All India Radio IMD Indian Meteorological Department ALM Advanced Locality Management ISRO Indian Space Research Organisation ANM Auxiliary Nurse/Midwife KEM King Edward Memorial Hospital BCS Bombay Catholic Sabha MCGM/B Municipal Council of Greater Mumbai/ BEST Brihan Mumbai Electric Supply & Bombay Transport Undertaking. MCMT Mohalla Committee Movement Trust. BEAG Bombay Environmental Action Group MDMC Mumbai Disaster Management Committee BJP Bharatiya Janata Party MDMP Mumbai Disaster Management Plan BKC Bandra Kurla Complex. MoEF Ministry of Environment and Forests BMC Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation MHADA Maharashtra Housing and Area BNHS Bombay Natural History Society Development Authority BRIMSTOSWAD BrihanMumbai Storm MLA Member of Legislative Assembly Water Drain Project MMR Mumbai Metropolitan Region BWSL Bandra Worli Sea Link MMRDA Mumbai Metropolitan Region CAT Conservation Action Trust Development Authority CBD Central Business District. MbPT Mumbai Port Trust CBO Community Based Organizations MTNL Mahanagar Telephone Nigam Ltd. CCC Concerned Citizens’ Commission MSDP Mumbai Sewerage Disposal Project CEHAT Centre for Enquiry into Health and MSEB Maharashtra State Electricity Board Allied Themes MSRDC Maharashtra State Road Development CG Coast Guard Corporation