Climate Change & Banff National Park : Implications for Tourism And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE LIFTLINE CMCA NEWSLETTER Issue Q4 2018

THE LIFTLINE CMCA NEWSLETTER Issue Q4 2018 THE LIFTLINE CMCA Newsletter REBECCA NEELS 2018/2019 EVENTS Every single year on the last day of the WondersIssue of Winter Date Dec 7 season, I am an emotional wreck. It’s always Kickoff Party so bittersweet. I didn’t think this was Opening Day (weather UNTETHERED possible, but each year, my love and passion Dec 14 for the program, its mission and those who permitting) are involved continues to grow. Even with all Full Moon Snowshoe & AT HEART Dec 21 the health challenges I have dealt with Fine Dining Experience recently, the thought of being able to get by Rebecca Neels Ski with Santa (11 am – back in my bucket soon and ski my freaking Dec 25 4 pm) CADS Alberta Vice-President heart out feels incredible. Upon reflection, there was something different about it this Powder Stagecoach Cat As I sit down to write this, my mind goes Dec 27 year. I felt freer, more euphoric and more Skiing begins back to where I am the happiest. My happy appreciative. In the past, I was so consumed place is sitting at the top of a Huckleberry CMCA Community with becoming the best possible skier and Dec 27 and anticipating the feeling of euphoria that achieving my ultimate goal of skiing Potluck Night 5:45pm floods through my insides like a giant tidal untethered. Even though my goal of skiing Night Skiing on Green Dec 29 – 31 wave as I soar down the mountain. I crave the untethered didn’t happen this season, I am Chair moment when my soul’s beast is unleashed not upset or frustrated with myself. -

Avalanche Information for Subscribers

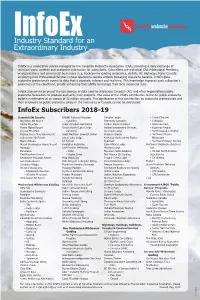

InfoEx Industry Standard for an Extraordinary Industry InfoEx is a cooperative service managed by the Canadian Avalanche Association (CAA), providing a daily exchange of technical snow, weather and avalanche information for subscribers. Subscribers are individual CAA Professional Members, or organizations and commercial businesses (e.g. backcountry guiding companies, ski hills, BC Highways, Parks Canada) employing CAA Professional Members whose operations require actively managing avalanche hazards. InfoEx gives avalanche professionals access to data that is accurate, relevant and real time. This knowledge improves each subscriber’s awareness of the conditions, greatly enhancing their ability to manage their local avalanche risks. InfoEx also serves as one of the key sources of data used by Avalanche Canada’s (AC) and other organizations public avalanche forecasters to produce and verify their products. The value of the InfoEx contribution to the AC public avalanche bulletin is estimated at an excess of $2 million annually. The significance of this contribution by avalanche professionals and their employers to public avalanche safety in the mountains of Canada cannot be overstated. InfoEx Subscribers 2018-19 Downhill Ski Resorts KPOW! Fortress Mountain Dezaiko Lodge • Coast/Chilcotin Big White Ski Resort Catskiing Extremely Canadian • Columbia Castle Mountain Great Canadian Heli-Skiing Golden Alpine Holidays • Kootenay Pass Fernie Alpine Resort Gostlin Keefer Lake Lodge Hyland Backcountry Services • Kootenay Region Grouse Mountain Catskiing Ice Creek Lodge • North Cascades District Kicking Horse Mountain Resort Great Northern Snowcat Skiing Kokanee Glacier • Northwest Region Lake Louise Ski Resort Island Lake Lodge Kootenay Backcountry Guides Ningunsaw Marmot Basin K3 Cat Ski Kyle Rast • Northwest Region Terrace Mount Washington Alpine Resort Kingfisher Heliskiing Lake O’Hara Lodge Northwest Avalanche Solutions Norquay Last Frontier Heliskiing Mistaya Lodge Ltd. -

The Big Chill

A very fine Wednesday culinary journey February 17, 2021 of Caribbean T: 582-7800 and Peruvian www.arubatoday.com fusion cuisine facebook.com/arubatoday instagram.com/arubatoday Page 10 Aruba’s ONLY English newspaper Millions endure record cold without power; at least 15 dead By BRYAN ANDERSON Associated Press OCEAN ISLE BEACH, N.C. (AP) — A winter storm that left millions without power in record-breaking cold weather claimed more THE BIG lives Tuesday, including three people found dead after a tornado hit a sea- side town in North Carolina and four family members CHILL who perished in a Houston- area house fire while using a fireplace to stay warm. The storm that over- whelmed power grids and immobilized the Southern Plains carried heavy snow and freezing rain into New England and the Deep South and left behind painfully low temperatures. Wind-chill warnings ex- tended from Canada into Mexico. In all, at least 15 deaths were reported. Other causes included car crash- A woman wrapped in a blanket crosses the street near downtown Dallas, Tuesday, Feb. 16, 2021. Temperatures dropped into the es and carbon monoxide single digits as snow shut down air travel and grocery stores. poisoning. The weather Associated Press also threatened to affect the nation's COVID-19 vac- County had little notice of ice was “very surprised how Director Ed Conrow said. normally balmy Gulf of cination effort. President the dangerous weather, rapidly this storm intensified In Chicago, a foot and a Mexico, cross-country skiier Joe Biden's administration and a tornado warning ... and at the time of night half (46 centimeters) of Sam Fagg hit fresh powder said delays in vaccine ship- was not issued until the when most people are at new snow forced public on the beach in Galveston, ments and deliveries were storm was already on the home and in bed, it cre- schools to cancel in-person Texas. -

Lake Louise Tour #1 Tour Level Is Moderate for Walking: 8:30 – We

Lake Louise Tour #1 Tour Level is moderate for walking: 8:30 – We will leave from designated pick-up point at Moon Travel, #3 – 3360 27 St, NE Calgary. Please have a photo ID with you and wear comfortable walking shoes and clothing, including some type of head covering. 9:30 – Stop for pit stop at Dead Man’s Flats. Dead Man's Flats is a hamlet in Alberta within the Municipal District of Bighorn No. 8. Statistics Canada also recognizes it as a designated place under the name of Pigeon Mountain. It is located within Alberta's Rockies at Highway 1 exit 98, approximately 7 kilometers southeast of Canmore and 78 kilometers west of Calgary. We will use the restrooms and clients can check out the souvenirs. 10:00 – 10:30 – Arrive in Banff. We will take a 15 minute stretch here. Banff is a town within Banff National Park in Alberta, Canada. It is located in Alberta's Rockies along the Trans-Canada Highway, approximately 126 km west of Calgary and 58 km east of Lake Louise. At 1,400 to 1,630 m above sea level, Banff is the community with the second highest elevation in Alberta, after Lake Louise. 10:30 -11:00 –Arrive in Lake Louise. The Lake Louise Ski Resort & Summer Gondola is a ski resort in western Canada, located in Banff National Park near the village of Lake Louise, Alberta. It is located 57 km west of Banff. Lake Louise is one of three major ski resorts located in Banff National Park. 12:00 – Lunch – Lake Louise Station Restaurant - A heritage railway station is home to this unique restaurant in Lake Louise where you can enjoy casual dining with such specialties as bison burgers, salmon, and Alberta beef tenderloin. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air Canada (Alberta – VE6/VA6) Association Reference Manual (ARM) Document Reference S87.1 Issue number 2.2 Date of issue 1st August 2016 Participation start date 1st October 2012 Authorised Association Manager Walker McBryde VA6MCB Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged Page 1 of 63 Document S87.1 v2.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) 1 Change Control ............................................................................................................................. 4 2 Association Reference Data ..................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Programme derivation ..................................................................................................................... 8 2.2 General information .......................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 Rights of way and access issues ..................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Maps and navigation .......................................................................................................................... 9 2.5 Safety considerations .................................................................................................................. -

Physiography and Related Sciences

28 PHYSIOGRAPHY AND RELATED SCIENCES 7.—Principal Heights in each Province and Territory NOTE.—Certain peaks, indicated by an asterisk (*), form part of the line of demarcation between political subdivisions. Although their bases technically form part of both areas, they are listed only under one to avoid duplication. Province and Height Elevation Province and Height ft. Newfoundland Quebec—concluded Long Range— Shield- Lewis Hills 2,672 Mount Tremblant Gros Morne 2,644 Mount Ste. Anne Mount St. Gregory 2,251 Mount Sir Wilfrid.... Gros Pate 2,152 Monteregian Hills— Blue Mountain 2,128 St. Hilaire Mountain. Table Mountain ,900-1,950 Yamaska Mountain.. Blue Hills of Coteau— Rougemont Peter Snout 1,600-1,650 Mount Johnson Central Highlands— Mount Royal Main Topsail 1,822 Mizzen Topsail 1,761 Torngats— Ontario Cirque Mountain 5,160 Mount Cladonia 4,725 Tip Top Hill Mount Eliot 4,550 Mount Batchawana.... Mount Tetragona 4,500 Niagara Escarpment— Quartzite Mountain 3,930 Osier Bluff Blow Me Down Mountain... 3,880 Caledon Mountain.... Kaumjets— Blue Mountain Bishops Mitre 4,060 High Hill Finger Hill 3,390 Mount Nemo Nova Scotia Manitoba (Spot height—Cape Breton) 1,747 Duck Mountain Ingonish Mountain 1,392 Porcupine Mountain. Nutby Mountain (Cobequid) 1,204 Riding Mountain Dalhousie Mountain (Cobequid) 1,115 North Mountain (4 miles NE of West Bay Saskatchewan Road) 875 Sporting Mountain 675 Cypress Hills1 Wood Mountain (West Summit). Wood Mountain (East Summit). New Brunswick Vermilion Hills Mount Carleton.. 2,690 Green Mountain. 1,596 Alberta Moose Mountain. 1,490 Rockies— •Mount Columbia Quebec The Twins (NPeak)..., Appalachians— Mount Forbes Mount Jacques Cartier (Shickshocks) 4,160 Mount Alberta Mount Richardson 3,885 •Mount Assiniboine Barn Mountain 3,775 The Twins (SPeak)... -

October 2010 • V Ol. 18, No. 5

October 2010 • Vol. 18, No. 5 Vol. October 2010 • AWA Moraine Lake from Mount Temple, Banff National Park PHOTO: © N. DOUGLAS THE ILLUSION OF INTEGRitY / 4 ALBERta’S PROPOSED NEW PARKS LEGISLatiON / 6 SORDID OR WELCOME? MOUNtaiN BIKES IN NatiONAL PARKS / 9 WILLMORE AS A WORLD HERitaGE SitE? / 13 FROM PRaiRIE TO POtatOES / 15 Editor: Ian Urquhart COctoONTENTSbEr 2010 • VOL. 18, NO. 5 Graphic Design: Marni Wilson FEATURES WILDERNESS WATCH Printing: HE LLUSION OF NTEGRITY UPDATES colour printing and process is sponsored 4 T I I 23 by Topline Printing WHAT IS HAPPENING WITH 6 THE NEW PROVINCIAL PARKS EPARTMENTS LEGISLATION? D 9 DO MOUNTAIN BIKES BELONG IN 26 GEAR THE BACKCOUNTRY? ABSOLUTELY. 27 READER’S CORNER 10 A SORDID AFFAIR: MOUNTAIN BIKING IN CANADA’S NATIONAL 28 RECALL OF THE WILD PARKS 13 THE WILLMORE: STRONGER EVENTS MANAGEMENT… WHAT’S SO EVIL ALbErta WILDErNESS ABOUT WORLD HERITAGE STATUS? 30 TUESDAY TALKS; MUSIC FOR THE ASSOciation WILD; AWARDS AND ANNUAL “Defending Wild Alberta through POTATOGATE: TURNING 15 LECTURE; AGM Awareness and Action” ENDANGERED SPECIES HABITAT INTO POTATO CHIPS 30 IN MEMORIAM: (NANCY) LOUISE Alberta Wilderness Association is a GUY charitable non-government organization dedicated to the completion of a ASSOCIATION NEWS protected areas network and the conservation of wilderness throughout the province. To support our work 17 NEWCOMERS TO WILD SPACES with a tax-deductible donation, call 403-283-2025 or contribute online SUNRISE ON A MOUNTAIN TOP 18 at AlbertaWilderness.ca. 21 PETER LEE: I KNOW MARTHA Wild Lands Advocate is published WOULD APPROVE bi-monthly, 6 times a year, by Alberta Wilderness Association. -

CANDIDATE 2025 AUDI FIS SKI WORLD CUP FINALS HAFJELL KVITFJELL AUDI FIS SKI WORLD CUP FINALS 2025 | 3 We Are Snow! It’S Our

CANDIDATE 2025 AUDI FIS SKI WORLD CUP FINALS HAFJELL KVITFJELL AUDI FIS SKI WORLD CUP FINALS 2025 | 3 We are snow! It’s our WELCOME TO THE ALPINE VALLEY The Lillehammer-region is one of the most important destinations for winter sport lovers of any age, not only in Europe but worldwide. The region offers speed and fun in a good old-fashioned winter setting. The Lillehammer and Gudbrandsdalen-region are Norway’s number one skiing destination, the five alpine centers have downhill runs ranging from pistes with World Cup standards, to slopes suitable for beginners and the very young. PHOTO GEIR OLSEN With five alpine centres where the downhill runs range from pistes of World Cup standard, to slopes suitable for beginners and the very young. In the skiing community, our region is renowned for its long and stable winters with excellent snow conditions. Every autumn and winter, national teams, elite skiers and various clubs and associations use the area for training camps. We take great pride in always offering the very best quality – good enough for the elite; «Kvitfjell shows good enough for recreational skiers. Furthermore, you do not have to drive far to reach Norway from it’s best!» the various activities. – Aksel Lund Svindal – AUDI FIS SKI WORLD CUP FINALS 2025 | 5 Travel and transport HOW TO ARRIVE ACCESS BY AIR: Easy and eco-friendly The gateway to Norway for teams, athletes and the other accredited groups participating, will be the Oslo International Airport Gardermoen, north of Oslo. ■ The Organizing Committee offer the Teams free pick ACCESS BY TRAIN: up at the Gardermoen All northbound trains (ca. -

LIMITED ENTRY HUNTING REGULATIONS SYNOPSIS 2021-2022 the 2021-2022 LEH Synopsis Was NOT PRINTED and Is ONLY Available Online

BRITISH COLUMBIA LIMITED ENTRY HUNTING REGULATIONS SYNOPSIS 2021-2022 The 2021-2022 LEH Synopsis was NOT PRINTED and is ONLY available online CLOSING DATE: APPLICATIONS MUST BE SUBMITTED BY 11:59 P.M. MAY 28, 2021 MINISTRY OF FORESTS, LANDS, NATURAL RESOURCE OPERATIONS AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT HONOURABLE KATRINE CONROY, MINISTER APPLY EARLY TO AVOID THE LAST MINUTE RUSH BC Hunting Online Service Who Can Apply? In 2016, the Province of British Columbia (B.C.) introduced the BC Hunting Any resident of British Columbia who holds a Fish and Wildlife ID with active online service, where you can purchase your Limited Entry Hunting B.C. resident and hunting credentials may apply. To be eligible to obtain a applications, hunting licences and species licences. We encourage you to take B.C. resident credential, hunters must be a B.C. resident as defined in the advantage of the BC Hunting online service. In the event that you need to visit Wildlife Act or qualify for an exemption. To obtain the hunting credential, a in person a Service BC, FrontCounter BC or vendor location, please check hunter must prove successful completion of hunter safety training such as the in advance the office hours of service and if applicable book an appointment. Conservation and Outdoor Recreation Education (CORE). Your Fish and Wildlife ID (FWID) The Province requires hunters to prove B.C. residency every three years. This will ensure only eligible hunters access hunting licences, permits You need a Fish and Wildlife ID (FWID) to buy hunting licences or submit and authorizations available to residents only. -

Husky Moose Mountain Pipeline: a Case Study of Planning, Environmental Assessment & Construction

2000 international Pipeline Conference — Volume 1 AS ME 2000 IPC2000-140 Downloaded from http://asmedigitalcollection.asme.org/IPC/proceedings-pdf/IPC2000/40245/V001T03A002/2507307/v001t03a002-ipc2000-140.pdf by guest on 24 September 2021 HUSKY MOOSE MOUNTAIN PIPELINE: A CASE STUDY OF PLANNING, ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT & CONSTRUCTION Carol J. Engstrom Husky Oil Operations Limited Guy M. Goulet Western Ecological Systems Management Consulting Inc. ABSTRACT In 1998, Husky Oil Operations Limited and its partner formerly INTRODUCTION & HISTORY 2 Rigel Oil, (purchased by Talisman Energy in 1999), constructed a Kananaskis' Country encompasses an area of over 4160 km 26.2 km pipeline in Kananaskis Country to transport sour oil, solution located southwest of Calgary. It is an area of high peaks, flowing gas and produced water from Pad #3 on Cox Hill to the Shell Oil streams, and home to many important mammals and fish, as well as a Jumping Pound Gas Plant for processing. Kananaskis Country is a heavily used recreation area. People from all over Alberta and 4160 km2 "Planning Area" that has both Prime Protection and Western Canada visit the area to hike, canoe, fish, snowmobile, Multiple Use designations. Situated just west of Calgary, Alberta, cycle, quad, ski and participate in a host of other outdoor pursuits. Canada it has considerable recreational and environmental value, Industrial activities such as cattle grazing, logging and oil & gas including significant wildlife habitat development also occur in Kananaskis Country. Although it is not a park, it is managed by an Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) and is The original exploration and subsequent pipeline construction nicknamed "Calgary's playground" (Figure 1). -

5 Day Mountain Moment Rail Journey

Tour Code 5MMRJ 5 Day Mountain Moment Rail Journey 5 days Created on: 27 Sep, 2021 Day 1: Calgary to Banff. Snowshoeing Excursion to Marble Canyon Travel by coach along a scenic section of Highway 1 from Calgary to Banff. Drop your bags off at the hotel and then an easy afternoon introductory snowshoeing tour experience. Travel to Kootenay National Park and admire the dramatic colours of Marble Canyon. See how the pounding and frozen waters of Tokumn Creek have eroded a 40-meter deep limestone gorge. Walkthrough the forest left standing from the 2003 Kootenay fire and search for snowshoe hare, moose and wolf tracks while exploring how the landscape is changing and animals are adapting. Overnight: Banff Day 2: Banff Day Ski Pass Banff National Park is home to one of the longest ski seasons in North America and three world-class ski areas, which are all located within 45 minutes of the Town of Banff: Mount Norquay, Sunshine Village, and the Lake Louise Ski Resort. Enjoy a full day of skiing or snowboarding and experience the "champagne powder" Banff is famous for. Overnight: Banff Day 3: Travel along the famous Icefields Parkway from Banff to Jasper Today, travel by coach on the iconic Icefield Parkway, one of the most scenic highways in the world and the main route connecting the resort towns of Jasper and Banff. Rich with wildlife, ancient glaciers and pristine lakes, keep your cameras handy as there is a photo opportunity at every curve along this road. Overnight: Jasper Day 4: Maligne Canyon Ice Walk or Marmot Basin Ski Pass The Maligne Canyon Icewalk Tour in Jasper, Alberta, is one of Jasper's most popular and impressive winter adventures. -

May 2017 Newsletter

FINALLY a May 24th long weekend that rocked! (We'll ignore the snow that came after it) If You Admire the View, You Are a Friend Of Kananaskis In this month's newsletter... Executive Director's Report TRAIL FEST - June 11 Upcoming Volunteer Opportunities Crew Leader Training Thanks for Cleaning Highway 40 News from the Board -- Ways you can help Kananaskis Safety In The Outdoors, Part 1: What to Know Before you Go Flowers of K-Country -- Calypso Orchids Executive Director's Report by Nancy Ouimet Celebrate Kananaskis Country 3rd Annual Trails Fest June 11 at the Canmore Nordic Centre Free for the whole family Trails Fest is a fun day of all things trails related. Learn about cool trail projects, explore diverse trail related clubs, groups and associations, and take part in facilitated trail activities, workshops and presentations. Invite all your trail enthusiast friends to join in! Event Itinerary 10:00 – 2:00 Connect with over 30 Clubs & Organizations, Screen ‘Living with Wildlife’ 12:00 Welcome with Banff - Cochrane MLA Cam Westhead and Canmore Town Councillor Ed Russel, BBQ Lunch (free) 1:30 – 3:00 Guided Activities & Workshops (hiking, biking, trail running, orienteering...and more) WORKSHOP SIGN UP - click on the topic you are interested in and register. All workshops are free of charge and begin at 1:30 pm. Bear Necessities Trail Running Monitoring Human Use of Wildlife Corridors in the Bow Valley around Canmore Introduction to Orienteering Map Reading Skills WildSmart on the Trail Trail Crew Orientation Maintaining Historic Horse Trails Organizations, groups and businesses exhibiting their work at TrailsFest.