Agricultural Co-Operative Trading in Wales: Its Development, Present Structure and Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Schedule.Pdf

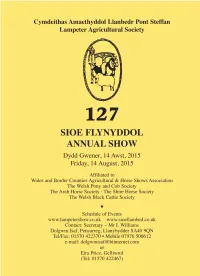

CYMDEITHAS AMAETHYDDOL LLANBEDR PONT STEFFAN LAMPETER AGRICULTURAL SOCIETY Llywyddion/Presidents — Mr Graham Bowen, Delyn-Aur, Llanwnen Is-Lywydd/Vice-President — Mr & Mrs Arwyn Davies, Pentre Farm, Llanfair Milfeddygon Anrhydeddus/Hon. Veterinary Surgeons — Davies & Potter Ltd., Veterinary Surgeons, 18 –20 Bridge Street, Lampeter Meddygon Anrhydeddus/Hon. Medical Officers — Lampeter Medical Practice, Taliesin Surgery Announcers — Mr David Harries, Mr Andrew Jones, Mr Andrew Morgan, Mr Gwynne Davies SIOE FLYNYDDOL/ ANNUAL SHOW to be held at Pontfaen fields, Lampeter SA48 7JN By kind permission of / drwy ganiatâd Mr & Mrs A. Hughes, Cwmhendryd Gwener/Friday, Awst/August 14, 2015 Mynediad/Admission : £8.00; Children under 14 £2.00 Enquiries to: I. Williams (01570) 422370 or Eira Price (01570) 422467 Schedules available on our Show website: www.lampetershow.co.uk • www.sioellambed.co.uk or from the Secretary – Please include a S.A.E. for £1.26 (1st class); £1.19 (2nd class) Hog Roast from 6 p.m. 1 CYMDEITHAS AMAETHYDDOL LLANBEDR PONT STEFFAN LAMPETER AGRICULTURAL SOCIETY SWYDDOGION A PHWYLLGOR Y SIOE/ SHOW OFFICIALS AND COMMITTEE Cadeirydd/Chairman — Miss Eira Price, Gelliwrol, Cwmann Is-Gadeirydd/Vice-Chairman — Miss Hâf Hughes, Cwmere, Felinfach Ysgrifenydd/Secretary— Mr I. Williams, Dolgwm Isaf, Pencarreg Trysorydd/Treasurer— Mr R. Jarman Trysorydd Cynorthwyol/Assistant Treasurer— Mr Bedwyr Davies (Lloyds TSB) AELODAU OES ANRHYDEDDUS/HONORARY LIFE MEMBERS Mr John P. Davies, Bryn Castell, Lampeter; Mr T. E. Price, Gelliwrol, Cwmann; Mr Andrew Jones, Cwmgwyn, Lampeter; Mr A. R. Evans, Maes yr Adwy, Silian; Mrs Gwen Jones, Gelliddewi Uchaf, Cwmann; Mr Gwynfor Lewis, Bronwydd, Lampeter; Mr Aeron Hughes, Cwmhendryd, Lampeter; Mrs Gwen Davies, Llys Aeron, Llanwnen; Mr Ronnie Jones, 14 Penbryn, Lampeter. -

Bow Street, Unawdwyr Gwyn Hughes Jones Yn Un a Ddewiswyd Ar Gyfer a Rebecca Evans Yn Eglwys Dewi Y Gyfres Radio ‘Cyfle Cothi’ Ar Sant, Caerdydd

PRIS 75c Rhif 334 Rhagfyr Y TINCER 2010 PAPUR BRO GENAU’R-GLYN, MELINDWR, TIRYMYNACH, TREFEURIG A’R BORTH CYFLE COTHI Mae Rhodri Evans, Bow Street, unawdwyr Gwyn Hughes Jones yn un a ddewiswyd ar gyfer a Rebecca Evans yn Eglwys Dewi y gyfres radio ‘Cyfle Cothi’ ar Sant, Caerdydd. Bydd rhaglen Radio Cymru lle bydd y gantores, Rhodri ar y radio amser cinio yr actores a’r cyflwynydd, Shân noswyl Nadolig - dydd Gwener, Cothi, yn rhoi cyfle i wrandawyr Rhagfyr 24 am 1.15pm. ddilyn hynt y perfformwyr. “Mae’r Meddai Rhodri, “Roedd cael rhaglen wedi rhoi cyfle arbennig i fy newis i gymryd rhan mewn dalent addawol o Gymru i ddysgu dosbarth meistr yn brofiad o brofiadau unawdwyr sydd wedi bythgofiadwy, roedd cael canu cyrraedd yr uchelfannau yn y gyda’m harwr yn rhywbeth byd perfformio heddiw,” meddai roeddwn yn gwerthfawrogi’n Shân Cothi. “Mae yna gymaint o fawr gan ei fod yn gallu unigolion talentog ym mhob cwr uniaethu â mi gan ei fod wedi o Gymru, a nod y rhaglen yw mynd o ganu bariton gwych i rhoi llwyfan i bob un o’r chwech fod yn denor hyd yn oed yn godi eu proffil. Mae yma chwe well, a gan mai ond ers tua unigolyn sydd wedi ymroi i loywi blwyddyn rwyf wedi canu’r eu sgiliau ac sy’n ysu i ddysgu a ystod tenor, mae cael rhywun datblygu yn sêr y dyfodol yng sydd â phrofiad yma yn un a Nghymru.” fydd yn aros yn y cof am amser yn broffesiynol, gan nad wyf Tenor.” Yn y llun gwelir Rhodri Yr her gafodd Rhodri oedd hir. -

Adroddiad Blynyddol / Annual Report 1974-75

ADRODDIAD BLYNYDDOL / ANNUAL REPORT 1974-75 WILLIAM GRIFFITHS 1975001 Ffynhonnell / Source The late Miss A G Jones, M.A., Aberaeron, per Miss Olive M Jones, Aberaeron. Blwyddyn / Year Adroddiad Blynyddol / Annual Report 1974-75 Disgrifiad / Description Correspondence, journals, diaries, etc., of Rev William Griffiths (1788-1861), Calvinistic Methodist minister in Gower, co. Glamorgan, including journals for the years 1816-19, 1822-7 (numbered vol. 5), 1827-34 (vol. 6), 1834-42 (vol. 7), 1842-7 (vol. 8), and 1848-55 (vol. 9) (for vol. 4, 1819-22, see Calvinistic Methodist Archives 8710); printed diaries 1837; 1943-5; 1850-1 (very few entries); a `day book' or diary, 1854-61, with additional entries at the end by his son also named William Griffiths; a note-book containing autobiographical data compiled at intervals ? up to 1860; thirteen letters, 1825-6, addressed by him to his future wife Miss A. G. Jones, and one letter, 1826, written by him to his wife; twenty-five miscellaneous letters, 1840-60 and undated, received by him; thirty letters, 1846-9 and undated, received by him and his wife from their son William; printed copies of reports and notices of general meetings of the Glamorganshire Banking Company, 1845-58, addressed to him; bundles of sermon notes, 1817-61 ; two note-books containing a record of subscriptions towards the support of the ministry at Bethesda Church, Gower, 1838-43; a manuscript volume described on the title-page as `A Series of Questions and Answers on the more prominent doctrines of the Holy Bible written for the use of the Sabbath Schools belonging to Burry Green and Cherriton Chaples (sic) by Rev. -

Inspection Report Ysgol Eifionydd 2018

A report on Ysgol Eifionydd Porthmadog Gwynedd LL49 9HS Date of inspection: April 2018 by Estyn, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate for Education and Training in Wales A report on Ysgol Eifionydd April 2018 About Ysgol Eifionydd Ysgol Eifionydd is a naturally bilingual secondary school for 11-16 year-old pupils. It is situated in the town of Porthmadog in Gwynedd, and pupils come from the towns of Porthmadog and Criccieth, and the rural area of Eifionydd. There are 364 pupils on roll, which is 67 fewer pupils than at the time of the last inspection in October 2011. Around 8.9% of pupils are eligible for free school meals, which is lower than the national figure of 17%. Seventeen per cent of pupils are on the school’s additional learning needs register, which is lower than the national average. Two point two per cent (2.2%) of pupils have a statement of special educational needs, which is very close to the national figure. Sixty-nine per cent of pupils come from Welsh-speaking homes. A very few pupils are from ethnic minority backgrounds. The headteacher has been in post since April 2016. The school’s senior management team includes the headteacher and two assistant headteachers. Further information is available from the Welsh Government My Local School website at the link below. http://mylocalschool.wales.gov.uk/Schools/SchoolSearch?lang=en 1 A report on Ysgol Eifionydd April 2018 Summary Ysgol Eifionydd is a close community with a caring and supportive ethos. Most pupils behave well and treat their teachers, visitors and peers with respect. -

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’). -

Felinfor / Aberclydan Brewery, Llanon. Delivery Addresses Dec 1868 – May 1869

Felinfor / Aberclydan Brewery, Llanon. Delivery addresses Dec 1868 – May 1869 Rec customer address customer Date customer name Forwarded by No 1 address 2 1 15/12/1868 Owen Jones Meirion Arms Aberystwyth 2 15/12/1868 Mr Davey Fountain Aberystwyth 3 15/12/1868 Evan Jones Raven Aberystwyth 4 15/12/1868 Miss Jenkins Chain & Anchor Aberystwyth 5 15/12/1868 David Jones 3 Horse Shoes Aberystwyth 6 15/12/1868 Thomas Brooks Unicorn Aberystwyth 7 15/12/1868 Morgan Morgans Cross Inn Jenkins 8 15/12/1868 John Evans Red Lion Ffosyffin Evans 9 16/12/1868 D Jones Ffostrasol Wm Evans 10 16/12/1868 David Davies Esq ?hydlow Llanrhystud J W Pugh 11 16/12/1868 JohnLlewelyn Cilcennin his son 12 16/12/1868 Mr Williams Blue Bell Aberystwyth 13 16/12/1868 David Davies Sailors Home Aberystwyth 14 16/12/1868 Rees Williams Derwenlas 15 16/12/1868 C Hale Coach builders Aberystwyth Arms 16 16/12/1868 Mr Davies by the lake? Brynfryn Arms 17 17/12/1868 John Williams Lime Kilns, Llanon self Aberstrincell 18 18/12/1868 Capt Lloyd Phillips Mabws Llanrhystud 19 18/12/1868 William Jenkins Berthlwyd himself 20 18/12/1868 Thomas Jones and Pengraig Penuwch J Jenkins son Mrgaret James 21 18/12/1868 Morgan Morgan Cross Inn J Jenkins son 22 19/12/1868 David Evans Swan Aberayron 23 19/12/1868 David Pugh Milford Tavern Aberayron 24 29/12/1868 John Jones Elephant & Castle Aberayron 25 19/12/1868 Mr Rowlands Canol? self 26 19/12/1868 Capt J Lloyd Ship Inn Llangrannog Evans 27 19/12/1868 Rev J Jones Vicarage Llanarth Evans 28 19/12/1868 John Lewis Cellie Llwyndafydd Evans 29 19/12/1868 Lewis Jenkins Llanon 30 22/12/1868 Mr Price Gafenan? 31 22/12/1868 mr E? Williams Maesbwlan Arms 32 22/12/1868 Bonsel Esq Glanrhydol 33 22/12/1868 Mr Williams Tynllydad 34 22/12/1868 Mr Edwards Rhydol Vale 35 22/12/1868 John Jones Green Castle Llanon 36 22/12/1868 Mr Jenkins Glanwern Ystrad his servant Felinfor / Aberclydan Brewery, Llanon. -

The Llyn Ac Eifionydd Junior Football League Constitutional Rules Part 1

TYMOR 2015-16 LLAWLYFR CLYBIAU Cynghrair Pêl -Droed Iau Llŷn & Eifionydd Junior Football League CLUBS HANDBOOK SEASON 2015 - 2016 1 SWYDDOGION Y GYNGHRAIR – LEAGUE OFFICERS SAFLE ENW CYFEIRIAD FFÔN E-BOST POSITION NAME ADDRESS PHONE E-MAIL CADEIRYDD Darren Vaughan Tegfryn 07949429380 CHAIRMAN Bryncrug LL36 9PA YSGRIFENNYDD SECRETARY IS-GADEIRYDD VICE CHAIRMAN YSGRIFENNYDD Colin Dukes 41 Adwy Ddu 01766770854 [email protected] GEMAU Penrhyndeudraeth anadoo.co.uk Gwynedd 07863348589 FIXTURE LL48 6AP SECRETARY YSGRIFENNYDD Vicky Jones Dolgellau COFRESTRU REGISTRATION SECRETARY SWYDDOG LLES Ivonica Jones Fflur y Main 01766 810671 tjones.llynsports@ Ty’n Rhos btinternet.com Chwilog, 07884161807 WELFARE Pwllheli OFFICER LL53 6SF TRYSORYDD Andrew Roberts 8 Bowydd View 07787522992 [email protected] Blaenau Ffestiniog m Gwynedd TREASURER LL41 3YW NWCFA REP Chris Jones Pentwyll 01758740521 [email protected] Mynytho 07919098565 Pwllheli CYN. NWCFA LL53 7SD 2 CLYBIAU A’U TIMAU - CLUBS AND THEIR TEAMS U6 U8 U10 U12 U14 U16 BARMOUTH JUNIORS X2 BLAENAU AMATEURS BRO DYSYNNI BRO HEDD WYN CELTS DOLGELLAU LLANYSTUMDWY PENLLYN – NEFYN PENRHYN JUNIORS PORTHMADOG JUNIORS PWLLHELI JUNIORS x 2 x 3 3 YSGRIFENYDD CLYBIAU -– CLUB SECRETERIES CLWB CYSWLLT CYFEIRIAD CLUB CONTACT ADDRESS BARMOUTH JUNIORS Alan Mercer Wesley House 01341 529 Bennar Terrace [email protected] Barmouth GwyneddLL42 1BT BLAENAU AMATEURS Mr Andrew Roberts 8 Bowydd View 07787522992 Blaenau Ffestiniog [email protected] Gwynedd LL41 3YW BRO DYSYNNI Lorraine Rodgers Bryn Awel 01341250404 Llwyngwril 07882153373 Gwynedd [email protected] LL37 2JQ BRO HEDD WYN CELTS Gareth Lewis Bryn Eithin 07788553231 Bryn Eithin [email protected] Trawsfynydd Gwynedd DOLGELLAU Mr Stephen Parry BRYN Y GWIN UCHAF, 01341423935 DOLGELLAU. -

Gwynedd Archives, Caernarfon Record Office

GB 0219 XL1 Gwynedd Archives, Caernarfon Record Office This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 29946 The National Archives LORD LIEUTENANCY PAPERS 1775-1872 Including files relating to royal visits to Caernarfonshire 1946-1958 Catalogued by Mark Crispin Powell a student on the 1989/1990 U.C.N.W Archive Administration Course Catalogue Mark XL1/ Gwynedd Archives and Museums Service Caernarfon 1990 THE LORD LIEUTENANT This is the office of sovereign's deputy or viceroy in a county. The Lord Lieutenant is thus the chief executive authority in that county, through whom the policy decisions of the central government would be directed. Conversely he would represent the considerations of the county at Court and to the government. Because of these exalted duties the honour was usually given to the principal aristocratic landowner in the county. Deputy lieutenants would be appointed to carry out the directions given by him. The office also had the power to recommend, and so thus constitute, the Commission of the Peace, the body of justices of the peace or magistrates who supervised the legal and administrative systems of the county though the medium of their Quarter Sessions court. The Lord Lieutenant also had responsibility for local defence and accordingly controlled the county militia forces. This aspect of his work is dealt with in more detail in the second introduction. The collection catalogued below contains some of the working papers, mainly correspondence, of four successive Lord Lieutenants of Caernarvonshire and one future Lord Lieutenant as a Vice Lieutenant. -

Rhiwlas Estate Records, ()

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Rhiwlas Estate Records, () Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 05, 2017 Printed: May 05, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH This description follows NLW guidelines based on ISAD(G) Second Edition; AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/rhiwlas-estate-records archives.library .wales/index.php/rhiwlas-estate-records Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Rhiwlas Estate Records, Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 4 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 5 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Pwyntiau mynediad | -

The Earth and Timber Castles of the Llŷn Peninsula in Their

The Earth and Timber Castles of the Llŷn Peninsula in their Archaeological, Historical and Landscape Context Dissertation submitted for the award of Bachelor of Arts in Archaeology University of Durham, Department of Archaeology James Gareth Davies 2013 1 Contents List of figures 3-5 Acknowledgements 6 Survey Location 7 Abstract 8 Aims and Objectives 9 Chapter 1: Literature review 10-24 1.1: Earth and Timber castles: The Archaeological Context 10-14 1.2: Wales: The Historical Context 15-20 1.3: Study of Earth and Timber castles in Wales 20-23 1.4: Conclusions 23-24 Chapter 2: Y Mount, Llannor 25-46 2.1:Topographic data analysis 25-28 2.2: Topographical observations 29-30 2.3: Landscape context 30-31 2.4: Geophysical Survey 2.41: Methodology 32-33 2.42: Data presentation 33-37 2.43: Data interpretation 38-41 2.5: Documentary 41-43 2.6: Erosion threat 44-45 2.7: Conclusions: 45 2 Chapter 3: Llŷn Peninsula 46-71 3.1: Context 46-47 3.2: Survey 47 3.3: Nefyn 48-52 3.4: Abersoch 53-58 3.5: New sites 59 3.6: Castell Cilan 60-63 3.7: Tyddyn Castell 64-71 Chapter 4: Discussion 72-81 4.1 -Discussion of Earth and Timber castle interpretations in Wales 72-77 4.2- Site interpretation 78 4.3- Earth and Timber castle studies- The Future 79-80 Figure references 81-85 Bibliography 86-91 Appendix 1: Kingdom of Gwynedd Historical Chronology (mid 11th to mid 12th centuries) 92-94 Appendix 2: Excavated sites in Wales 95-96 Appendix 3: Ty Newydd, Llannor- Additional Resources 97-99 Appendix 4: Current North Wales site origin interpretations 100 3 List of figures 1. -

CPO Table 1 June 09

The Schedule Table 1 1 2 3 Number Extent, description and situation of the land Qualifying persons under paragraph 3 of Schedule 1 to the Acquisition of Land act 1981 on map Owners or reputed owners Lessees or reputed Tenants or reputed Occupiers lessees tenants (other than lessees) IN THE TOWN OF PORTHMADOG IN THE COUNTY OF GWYNEDD 1/1 12148 square metres of part of half width of Mr R Williams Mr I Williams - Mr I Williams the A487 and part of full width of the Dinam Hall Ty Canol Ty Canol A498 at the junction between the Llangaffo Golan Golan A498 and A487 including part Gaerwen Garndolbenmaen Garndolbenmaen lengths of masonry highway Gwynedd Gwynedd Gwynedd boundary walls, part of full width of LL60 6LR LL51 9RQ LL51 9RQ an existing drainage ditch and pasture land in fields 0101, 0104, 0106 (A) and 0207(B) west of Tremadog. 1/1a 514 square metres of pasture land in Mr R Williams Mr I Williams - Mr I Williams field 0101(A) south of the A487 Dinam Hall Ty Canol Ty Canol Trunk road opposite Ysbyty Alltwen Llangaffo Golan Golan Community Hospital. Gaerwen Garndolbenmaen Garndolbenmaen Gwynedd Gwynedd Gwynedd LL60 6LR LL51 9RQ LL51 9RQ 1/1b 62 square metres of pasture land in Mr R Williams Mr I Williams - Mr I Williams field 0101(A) south of the A487 Dinam Hall Ty Canol Ty Canol Trunk road opposite Ysbyty Alltwen Llangaffo Golan Golan Community Hospital. Gaerwen Garndolbenmaen Garndolbenmaen Gwynedd Gwynedd Gwynedd LL60 6LR LL51 9RQ LL51 9RQ 1/1c 23 square metres of part of full width of Mr R Williams Mr I Williams Mr I Williams an existing drainage ditch between Dinam Hall Ty Canol Ty Canol fields 0101 and 0104(A) west of Llangaffo Golan Golan Tremadog. -

TŶ MAWR (Formerly the Castle Inn)

NORTH WEST WALES DENDROCHRONOLOGY PROJECT DATING OLD WELSH HOUSES - Caernarfonshire TŶ MAWR (formerly The Castle Inn) 2 and 4 Castle Street, Cricieth, Gwynedd (formerly Caernarfonshire) Parish: Cricieth Grid Reference: SH 5004 3785 © Crown copyright: Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales: Dating Old Welsh Houses: North West Wales Dendrochronology Project HOUSE DETAILS: Tŷ Mawr is a substantial house of Snowdonian type presenting several features of mid/later sixteenth century date including voussoir-headed openings, and two tiers of cusped windbraces. The timber is unusually well dressed with the removal of all sapwood. The principal chamber has a hooded fireplace and open archbraced truss. Published account in RCAHMW’s Inventory, Caernarvonshire, Volume II: Central (1960), pp. 62-3, no. 873, with an additional survey commissioned by the NWWDP available in NMRW (NPRN 32) (Richard Suggett, RCAHMW). Cantref: Dunoding Commote: Eifionydd (Atlas of Caernarvonshire pp 69-71). Dendrochronology results: Felling date range: After 1527. Lower purlin 1516; Beam (0/1). Site Master 1431-1516 gwyg2 (t = 7.1 SKERHS2; 6.1 CEFNCAR1; 6.0 CROWLE2) (Oxford Dendrochronology Laboratory [ODL]). The removal of the sapwood precludes the determination of an exact date: at least eleven rings are missing. SUMMARY: Tŷ Mawr may be of greatest significance as one of very few sites in Wales definitely associated with an early modern practitioner of medicine: it was also known as ‘Tu William feddig’, the house of William the Doctor. Little is known of this man, but it is likely that he practised in the late sixteenth-early seventeenth century. It is not known whether Tŷ Mawr was built for him, or occupied by him later.