Cladosporium) Or Both Transverse and Longitudinal (Such As Pithomyces and Alternaria), Or Irregular (Such As Epicoccum)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 5 Chapter 1 Introduction I. LIFE CYCLES and DIVERSITY of VASCULAR PLANTS the Subjects of This Thesis Are the Pteri

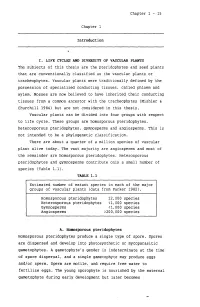

Chapter 1-15 Chapter 1 Introduction I. LIFE CYCLES AND DIVERSITY OF VASCULAR PLANTS The subjects of this thesis are the pteridophytes and seed plants that are conventionally classified as the vascular plants or tracheophytes. Vascular plants were traditionally defined by the possession of specialized conducting tissues, called phloem and xylem. Mosses are now believed to have inherited their conducting tissues from a common ancestor with the tracheophytes (Mishler & Churchill 1984) but are not considered in this thesis. Vascular plants can be divided into four groups with respect to life cycle. These groups are homosporous pteridophytes, heterosporous pteridophytes, gymnosperms and angiosperms. This is not intended to be a phylogenetic classification. There are about a quarter of a million species of vascular plant alive today. The vast majority are angiosperms and most of the remainder are homosporous pteridophytes. Heterosporous pteridophytes and gymnosperms contribute only a small number of species (Table 1.1). TABLE 1.1 Estimated number of extant species in each of the major groups of vascular plants (data from Parker 1982). Homosporous pteridophytes 12,000 species Heterosporous pteridophytes <1,000 species Gymnosperms <1,000 species Angiosperms >200,000 species A. Homosporous pteridophytes Homosporous pteridophytes produce a single type of spore. Spores are dispersed and develop into photosynthetic or mycoparasitic gametophytes. A gametophyte's gender is indeterminate at the time of spore dispersal, and a single gametophyte may produce eggs and/or sperm. Sperm are motile, and require free water to fertilize eggs. The young sporophyte is nourished by the maternal gametophyte during early development but later becomes Chapter 1-16 nutritionally independent. -

Ergot Alkaloids Mycotoxins in Cereals and Cereal-Derived Food Products: Characteristics, Toxicity, Prevalence, and Control Strategies

agronomy Review Ergot Alkaloids Mycotoxins in Cereals and Cereal-Derived Food Products: Characteristics, Toxicity, Prevalence, and Control Strategies Sofia Agriopoulou Department of Food Science and Technology, University of the Peloponnese, Antikalamos, 24100 Kalamata, Greece; [email protected]; Tel.: +30-27210-45271 Abstract: Ergot alkaloids (EAs) are a group of mycotoxins that are mainly produced from the plant pathogen Claviceps. Claviceps purpurea is one of the most important species, being a major producer of EAs that infect more than 400 species of monocotyledonous plants. Rye, barley, wheat, millet, oats, and triticale are the main crops affected by EAs, with rye having the highest rates of fungal infection. The 12 major EAs are ergometrine (Em), ergotamine (Et), ergocristine (Ecr), ergokryptine (Ekr), ergosine (Es), and ergocornine (Eco) and their epimers ergotaminine (Etn), egometrinine (Emn), egocristinine (Ecrn), ergokryptinine (Ekrn), ergocroninine (Econ), and ergosinine (Esn). Given that many food products are based on cereals (such as bread, pasta, cookies, baby food, and confectionery), the surveillance of these toxic substances is imperative. Although acute mycotoxicosis by EAs is rare, EAs remain a source of concern for human and animal health as food contamination by EAs has recently increased. Environmental conditions, such as low temperatures and humid weather before and during flowering, influence contamination agricultural products by EAs, contributing to the Citation: Agriopoulou, S. Ergot Alkaloids Mycotoxins in Cereals and appearance of outbreak after the consumption of contaminated products. The present work aims to Cereal-Derived Food Products: present the recent advances in the occurrence of EAs in some food products with emphasis mainly Characteristics, Toxicity, Prevalence, on grains and grain-based products, as well as their toxicity and control strategies. -

Reproduction in Plants Which But, She Has Never Seen the Seeds We Shall Learn in This Chapter

Reproduction in 12 Plants o produce its kind is a reproduction, new plants are obtained characteristic of all living from seeds. Torganisms. You have already learnt this in Class VI. The production of new individuals from their parents is known as reproduction. But, how do Paheli thought that new plants reproduce? There are different plants always grow from seeds. modes of reproduction in plants which But, she has never seen the seeds we shall learn in this chapter. of sugarcane, potato and rose. She wants to know how these plants 12.1 MODES OF REPRODUCTION reproduce. In Class VI you learnt about different parts of a flowering plant. Try to list the various parts of a plant and write the Asexual reproduction functions of each. Most plants have In asexual reproduction new plants are roots, stems and leaves. These are called obtained without production of seeds. the vegetative parts of a plant. After a certain period of growth, most plants Vegetative propagation bear flowers. You may have seen the It is a type of asexual reproduction in mango trees flowering in spring. It is which new plants are produced from these flowers that give rise to juicy roots, stems, leaves and buds. Since mango fruit we enjoy in summer. We eat reproduction is through the vegetative the fruits and usually discard the seeds. parts of the plant, it is known as Seeds germinate and form new plants. vegetative propagation. So, what is the function of flowers in plants? Flowers perform the function of Activity 12.1 reproduction in plants. Flowers are the Cut a branch of rose or champa with a reproductive parts. -

Revised Glossary for AQA GCSE Biology Student Book

Biology Glossary amino acids small molecules from which proteins are A built abiotic factor physical or non-living conditions amylase a digestive enzyme (carbohydrase) that that affect the distribution of a population in an breaks down starch ecosystem, such as light, temperature, soil pH anaerobic respiration respiration without using absorption the process by which soluble products oxygen of digestion move into the blood from the small intestine antibacterial chemicals chemicals produced by plants as a defence mechanism; the amount abstinence method of contraception whereby the produced will increase if the plant is under attack couple refrains from intercourse, particularly when an egg might be in the oviduct antibiotic e.g. penicillin; medicines that work inside the body to kill bacterial pathogens accommodation ability of the eyes to change focus antibody protein normally present in the body acid rain rain water which is made more acidic by or produced in response to an antigen, which it pollutant gases neutralises, thus producing an immune response active site the place on an enzyme where the antimicrobial resistance (AMR) an increasing substrate molecule binds problem in the twenty-first century whereby active transport in active transport, cells use energy bacteria have evolved to develop resistance against to transport substances through cell membranes antibiotics due to their overuse against a concentration gradient antiretroviral drugs drugs used to treat HIV adaptation features that organisms have to help infections; they -

Heterospory: the Most Iterative Key Innovation in the Evolutionary History of the Plant Kingdom

Biol. Rej\ (1994). 69, l>p. 345-417 345 Printeii in GrenI Britain HETEROSPORY: THE MOST ITERATIVE KEY INNOVATION IN THE EVOLUTIONARY HISTORY OF THE PLANT KINGDOM BY RICHARD M. BATEMAN' AND WILLIAM A. DiMlCHELE' ' Departments of Earth and Plant Sciences, Oxford University, Parks Road, Oxford OXi 3P/?, U.K. {Present addresses: Royal Botanic Garden Edinburiih, Inverleith Rojv, Edinburgh, EIIT, SLR ; Department of Geology, Royal Museum of Scotland, Chambers Street, Edinburgh EHi ijfF) '" Department of Paleohiology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC^zo^bo, U.S.A. CONTENTS I. Introduction: the nature of hf^terospon' ......... 345 U. Generalized life history of a homosporous polysporangiophyle: the basis for evolutionary excursions into hetcrospory ............ 348 III, Detection of hcterospory in fossils. .......... 352 (1) The need to extrapolate from sporophyte to gametophyte ..... 352 (2) Spatial criteria and the physiological control of heterospory ..... 351; IV. Iterative evolution of heterospory ........... ^dj V. Inter-cladc comparison of levels of heterospory 374 (1) Zosterophyllopsida 374 (2) Lycopsida 374 (3) Sphenopsida . 377 (4) PtiTopsida 378 (5) f^rogymnospermopsida ............ 380 (6) Gymnospermopsida (including Angiospermales) . 384 (7) Summary: patterns of character acquisition ....... 386 VI. Physiological control of hetcrosporic phenomena ........ 390 VII. How the sporophyte progressively gained control over the gametophyte: a 'just-so' story 391 (1) Introduction: evolutionary antagonism between sporophyte and gametophyte 391 (2) Homosporous systems ............ 394 (3) Heterosporous systems ............ 39(1 (4) Total sporophytic control: seed habit 401 VIII. Summary .... ... 404 IX. .•Acknowledgements 407 X. References 407 I. I.NIRODUCTION: THE NATURE OF HETEROSPORY 'Heterospory' sensu lato has long been one of the most popular re\ie\v topics in organismal botany. -

Congolius, a New Genus of African Reed Frog Endemic to The

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Congolius, a new genus of African reed frog endemic to the central Congo: A potential case of convergent evolution Tadeáš Nečas1,2*, Gabriel Badjedjea3, Michal Vopálenský4 & Václav Gvoždík1,5* The reed frog genus Hyperolius (Afrobatrachia, Hyperoliidae) is a speciose genus containing over 140 species of mostly small to medium-sized frogs distributed in sub-Saharan Africa. Its high level of colour polymorphism, together with in anurans relatively rare sexual dichromatism, make systematic studies more difcult. As a result, the knowledge of the diversity and taxonomy of this genus is still limited. Hyperolius robustus known only from a handful of localities in rain forests of the central Congo Basin is one of the least known species. Here, we have used molecular methods for the frst time to study the phylogenetic position of this taxon, accompanied by an analysis of phenotype based on external (morphometric) and internal (osteological) morphological characters. Our phylogenetic results undoubtedly placed H. robustus out of Hyperolius into a common clade with sympatric Cryptothylax and West African Morerella. To prevent the uncovered paraphyly, we place H. robustus into a new genus, Congolius. The review of all available data suggests that the new genus is endemic to the central Congolian lowland rain forests. The analysis of phenotype underlined morphological similarity of the new genus to some Hyperolius species. This uniformity of body shape (including cranial shape) indicates that the two genera have either retained ancestral morphology or evolved through convergent evolution under similar ecological pressures in the African rain forests. African reed frogs, Hyperoliidae Laurent, 1943, are presently encompassing almost 230 species in 17 genera. -

Isolation of Fungal Cellulase Gene Transcript from Penicillium Spinulosum

Isolation of fungal cellulase gene transcript from Penicillium spinulosum A Master’s Thesis Presented to the faculty of The College of Science and Mathematics Colorado State University – Pueblo In Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Biochemistry By Srivatsan Parthasarathy Colorado State University – Pueblo May, 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my research mentor Dr. Sandra Bonetti for guiding me through my research thesis and helping me in difficult times during my Master’s degree. I would like to thank Dr. Dan Caprioglio for helping me plan my experiments and providing the lab space and equipment. I would like to thank the department of Biology and Chemistry for supporting me through assistantships and scholarships. I would like to thank my wife Vaishnavi Nagarajan for the emotional support that helped me complete my degree at Colorado State University – Pueblo. III TABLE OF CONTENTS 1) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS …………………………………………………….III 2) TABLE OF CONTENTS …………………………………………………….....IV 3) ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………..V 4) LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………..VI 5) LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………VII 6) INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………1 7) MATERIALS AND METHODS………………………………………………..24 8) RESULTS………………………………………………………………………..50 9) DISCUSSION…………………………………………………………………….77 10) REFERENCES…………………………………………………………………...99 11) THESIS PRESENTATION SLIDES……………………………………………...113 IV ABSTRACT Cellulose and cellulosic materials constitute over 85% of polysaccharides in landfills. Cellulose is also the most abundant organic polymer on earth. Cellulose digestion yields simple sugars that can be used to produce biofuels. Cellulose breaks down to form compounds like hemicelluloses and lignins that are useful in energy production. Industrial cellulolysis is a process that involves multiple acidic and thermal treatments that are harsh and intensive. -

DNA Barcoding of Fungi in the Forest Ecosystem of the Psunj and Papukissn Mountains 1847-6481 in Croatia Eissn 1849-0891

DNA Barcoding of Fungi in the Forest Ecosystem of the Psunj and PapukISSN Mountains 1847-6481 in Croatia eISSN 1849-0891 OrIGINAL SCIENtIFIC PAPEr DOI: https://doi.org/10.15177/seefor.20-17 DNA barcoding of Fungi in the Forest Ecosystem of the Psunj and Papuk Mountains in Croatia Nevenka Ćelepirović1,*, Sanja Novak Agbaba2, Monika Karija Vlahović3 (1) Croatian Forest Research Institute, Division of Genetics, Forest Tree Breeding and Citation: Ćelepirović N, Novak Agbaba S, Seed Science, Cvjetno naselje 41, HR-10450 Jastrebarsko, Croatia; (2) Croatian Forest Karija Vlahović M, 2020. DNA Barcoding Research Institute, Division of Forest Protection and Game Management, Cvjetno naselje of Fungi in the Forest Ecosystem of the 41, HR-10450 Jastrebarsko; (3) University of Zagreb, School of Medicine, Department of Psunj and Papuk Mountains in Croatia. forensic medicine and criminology, DNA Laboratory, HR-10000 Zagreb, Croatia. South-east Eur for 11(2): early view. https://doi.org/10.15177/seefor.20-17. * Correspondence: e-mail: [email protected] received: 21 Jul 2020; revised: 10 Nov 2020; Accepted: 18 Nov 2020; Published online: 7 Dec 2020 AbStract The saprotrophic, endophytic, and parasitic fungi were detected from the samples collected in the forest of the management unit East Psunj and Papuk Nature Park in Croatia. The disease symptoms, the morphology of fruiting bodies and fungal culture, and DNA barcoding were combined for determining the fungi at the genus or species level. DNA barcoding is a standardized and automated identification of species based on recognition of highly variable DNA sequences. DNA barcoding has a wide application in the diagnostic purpose of fungi in biological specimens. -

Cladosporium Lebrasiae, a New Fungal Species Isolated from Milk Bread Rolls in France

fungal biology 120 (2016) 1017e1029 journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/funbio Cladosporium lebrasiae, a new fungal species isolated from milk bread rolls in France Josiane RAZAFINARIVOa, Jean-Luc JANYa, Pedro W. CROUSb, Rachelle LOOTENa, Vincent GAYDOUc, Georges BARBIERa, Jerome^ MOUNIERa, Valerie VASSEURa,* aUniversite de Brest, EA 3882, Laboratoire Universitaire de Biodiversite et Ecologie Microbienne, ESIAB, Technopole^ Brest-Iroise, 29280 Plouzane, France bCBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre, P.O. Box 85167, 3508 AD Utrecht, The Netherlands cMeDIAN-Biophotonique et Technologies pour la Sante, Universite de Reims Champagne-Ardenne, FRE CNRS 3481 MEDyC, UFR de Pharmacie, 51 rue Cognacq-Jay, 51096 Reims cedex, France article info abstract Article history: The fungal genus Cladosporium (Cladosporiaceae, Dothideomycetes) is composed of a large Received 12 February 2016 number of species, which can roughly be divided into three main species complexes: Cla- Received in revised form dosporium cladosporioides, Cladosporium herbarum, and Cladosporium sphaerospermum. The 29 March 2016 aim of this study was to characterize strains isolated from contaminated milk bread rolls Accepted 15 April 2016 by phenotypic and genotypic analyses. Using multilocus data from the internal transcribed Available online 23 April 2016 spacer ribosomal DNA (rDNA), partial translation elongation factor 1-a, actin, and beta- Corresponding Editor: tubulin gene sequences along with Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and Matthew Charles Fisher morphological observations, three isolates were identified as a new species in the C. sphaer- ospermum species complex. This novel species, described here as Cladosporium lebrasiae,is Keywords: phylogenetically and morphologically distinct from other species in this complex. Cladosporium sphaerospermum ª 2016 British Mycological Society. -

§ 112 Implications for Genus Claims Lisa Larrimore Ouellette Genus and Species Claims

Advanced Patent Law Institute: Silicon Valley § 112 Implications for Genus Claims Lisa Larrimore Ouellette Genus and Species Claims genus fastener species screw R1 mammalian insulin cDNA R2 CH CH sequence 2 3 for rat CH3 insulin cDNA Genus and Species Claims: Anticipation . Single species always anticipates genus. Genus anticipates species only if species can be “at once envisaged” from genus. Generic chemical formula that represents limited number of compounds that PHOSITA can easily draw or name anticipates each compound. Generic chemical formula for vast number of compounds doesn’t anticipate each—and such a claim likely has § 112 problems… Genus and Species Claims: Section 112 . How can a patentee adequately describe and enable a genus? . When does a generic disclosure describe and enable a species? genus Disclosures required by § 112 serve not species just teaching function but also evidentiary function—showing what inventor actually possessed. Key policy lever for limiting claim scope to inventive contribution. Genus and Species Claims: Section 112 . How can a patentee adequately describe and enable a genus? . Ariad v. Eli Lilly . What is a representative number of species? . When is functional claiming ok? . When do you have to enable and describe unrecited elements? . Are § 112 genus claims only problematic in biotech? Ariad v. Eli Lilly (en banc 2010) . Genus claims for all methods of reducing binding of a certain transcription factor. inadequate description . Need “disclosure of either a representative number of species … or structural features common to the members of the genus so that one of skill in the art can ‘visualize or recognize’ the members of the genus.” . -

Occasional Papers of the Museum of Zoology University of Michigan Ann Arbor,Michigan

OCCASIONAL PAPERS OF THE MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN ANN ARBOR,MICHIGAN THE NEOTROPICAL GENUS PAZZUS (MECOPTERA: BITTACIDAE) I)ISC.OTIIRY 01 speclmeils of the unusual bittacid genus Pazzus in the Mecoptera collection of the Univeisity of Michigan Museum of Zoology led to an euainination of what little has been written about this genus. Appaiently, only tllice spccirnens have hitherto been known to science. A single male, collected in Peiu, was described by Nav,is in 1908 as Bzllacu~graczl!~. Five years later Navis concluded that this rem'ukable insect repiesented a new genus, which he named Ynzzzlr iln honor 01 Diego Alvarez tlc Paz, S.J. In the preparation of his 1921 monograph ot the Mecoptera of the wolld, Esben-Petersen ex,~inincd one male and onc lemale of P~rzrusfrom Panama, in the tollection 01 the British Museum. These he identified as Pnzzus gtnczlzs Nakis, at the same time presenting a sketch of the inale genitalia slid a pllotograph of the wings. For the past thirty-five years no furtl-~erspecimens 01 Pnz2us have been nlcntioned in entomological litelature. Illustlations ot wings oT Pnzr~,~in Navis' 1913 papel and Esben- Petersen's nronograph indicate cleai ly that the Pel u and Panama specilllens 'lie of one genus, for the ~enationancl shape of wing are tonspicuously different from those of all other bittacid genera. How- ever, on comparing Nakbs' original description 01 Bzttaczlr graczlzs with my notes on the British Mlrseum specimens so named, it is evident to me that there are two species involved. A female in the Unive~sity of ~idhi~aicollection, taken in a light trap at l'eiia Illanca, Los Santos, Panama, about 175 miles from the locality lrom which tlhe specimens in the British Museum came, appears to be tonspecihc with them. -

Penicillium on Stored Garlic (Blue Mold)

Penicillium on stored garlic (Blue mold) Cause Penicillium hirsutum Dierckx (syn. P.corymbiferum Westling) Occurrence P. hirsutum seems to be the most common and widespread species occurring in storage. This disease occurs at harvest and in storage. Symptoms In storage, initial symptoms are seen as water soaked areas on the outer surfaces of scales. This leads to development of the green-blue, powdery mold on the surface of the lesions. When the bulbs are cut, these lesions are seen as tan or grey colored areas. There may be total deterioration with a secondary watery rot. Penicillium sp. causing a blue-green rot of a garlic head Photo by Melodie Putnam Penicillium sp. on garlic clove Photo by Melodie Putnam Disease Cycle Penicillium survives in infected bulbs and cloves from one season to the next. Spores from infected heads are spread when they are cracked prior to planting. If slightly infected cloves are planted, they may rot before plants come up, or the seedlings may not survive. The fungus does not persist in the soil. Close-up of Penicillium sp. on garlic headad Air-borne spores often invade plants through Photo by Melodie Putnam wounds, bruises or uncured neck tissue. In storage, infection on contact is through surface wounds or through the basal plate; the fungus grows through the fleshy tissue and sporulation occurs on the surface of the lesions. Entire cloves may eventually be filled with spores. Susan B. Jepson, OSU Plant Clinic, 1089 Cordley Hall, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331-2903 10/23/2008 Management ● Cure bulbs rapidly at harvest ● Avoid wounds or injury to bulbs at harvest, and separate those with insect damage ● Plant cloves soon after cracking heads ● Eliminate infected seed prior to planting ● Store at low temperatures (40 F prevents growth and sporulation), with low humidity and good ventilation References Bertolini, P.