ASH 2.1F-Mackie-LA in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue of the Earl Marshal's Papers at Arundel

CONTENTS CONTENTS v FOREWORD by Sir Anthony Wagner, K.C.V.O., Garter King of Arms vii PREFACE ix LIST OF REFERENCES xi NUMERICAL KEY xiii COURT OF CHIVALRY Dated Cases 1 Undated Cases 26 Extracts from, or copies of, records relating to the Court; miscellaneous records concerning the Court or its officers 40 EARL MARSHAL Office and Jurisdiction 41 Precedence 48 Deputies 50 Dispute between Thomas, 8th Duke of Norfolk and Henry, Earl of Berkshire, 1719-1725/6 52 Secretaries and Clerks 54 COLLEGE OF ARMS General Administration 55 Commissions, appointments, promotions, suspensions, and deaths of Officers of Arms; applications for appointments as Officers of Arms; lists of Officers; miscellanea relating to Officers of Arms 62 Office of Garter King of Arms 69 Officers of Arms Extraordinary 74 Behaviour of Officers of Arms 75 Insignia and dress 81 Fees 83 Irregularities contrary to the rules of honour and arms 88 ACCESSIONS AND CORONATIONS Coronation of King James II 90 Coronation of King George III 90 Coronation of King George IV 90 Coronation of Queen Victoria 90 Coronation of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra 90 Accession and Coronation of King George V and Queen Mary 96 Royal Accession and Coronation Oaths 97 Court of Claims 99 FUNERALS General 102 King George II 102 Augusta, Dowager Princess of Wales 102 King George III 102 King William IV 102 William Ewart Gladstone 103 Queen Victoria 103 King Edward VII 104 CEREMONIAL Precedence 106 Court Ceremonial; regulations; appointments; foreign titles and decorations 107 Opening of Parliament -

What Are the Different Types of Armorial Bearings?

FAQ Grants of Arms Who may apply for a Grant of armorial bearings? All Canadian citizens or corporate bodies (municipalities, societies, associations, institutions, etc.) may petition to receive a grant of armorial bearings. What are the different types of armorial bearings? Three categories of armorial bearings can be requested: coats of arms, flags and badges. A coat of arms is centred on a shield and may be displayed with a helmet, mantling, a crest and a motto (see Annex 1). A grant of supporters is limited to corporate bodies and to some individuals in specific categories. What is the meaning of a Grant of Arms? Grants of armorial bearings are honours from the Canadian Crown. They provide recognition for Canadian individuals and corporate bodies and the contributions they make both in Canada and elsewhere. How does one apply for Arms? Canadian citizens or corporate bodies desiring to be granted armorial bearings by lawful authority must send to the Chief Herald of Canada a letter stating the wish "to receive armorial bearings from the Canadian Crown under the powers exercised by the Governor General." Grants of armorial bearings, as an honour, recognize the contribution made to the community by the petitioner (either individual or corporate). The background information is therefore an important tool for the Chief Herald of Canada to assess the eligibility of the request. What background information should individuals forward? Individuals should forward: (1) proof of Canadian citizenship; (2) a current biographical sketch that includes educational and employment background, as well as details of voluntary and community service. They will also be asked to complete a personal information form protected under the Privacy Act, and may be asked for names of persons to be contacted as confidential references. -

“Powerful Arms and Fertile Soil”

“Powerful Arms and Fertile Soil” English Identity and the Law of Arms in Early Modern England Claire Renée Kennedy A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History and Philosophy of Science University of Sydney 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My greatest thanks and appreciation to Ofer Gal, who supervised my PhD with constant interest, insightfulness and support. This thesis owes so much to his helpful conversation and encouraging supervision and guidance. I have benefitted immensely from the suggestions and criticisms of my examiners, John Sutton, Nick Wilding, and Anthony Grafton, to whom I owe a particular debt. Grafton’s suggestion during the very early stages of my candidature that the quarrel between William Camden and Ralph Brooke might provide a promising avenue for research provided much inspiration for the larger project. I am greatly indebted to the staff in the Unit for History and Philosophy of Science: in particular, Hans Pols for his unwavering support and encouragement; Daniela Helbig, for providing some much-needed motivation during the home-stretch; and Debbie Castle, for her encouraging and reassuring presence. I have benefitted immensely from conversations with friends, in and outside the Unit for HPS. This includes, (but is not limited to): Megan Baumhammer, Sahar Tavakoli, Ian Lawson, Nick Bozic, Gemma Lucy Smart, Georg Repnikov, Anson Fehross, Caitrin Donovan, Stefan Gawronski, Angus Cornwell, Brenda Rosales and Carrie Hardie. My particular thanks to Kathryn Ticehurst and Laura Sumrall, for their willingness to read drafts, to listen, and to help me clarify my thoughts and ideas. My thanks also to the Centre for Editing Lives and Letters, University College London, and the History of Science Program, Princeton University, where I benefitted from spending time as a visiting research student. -

Town Unveils New Flag & Coat of Arms

TOWN UNVEILS NEW FLAG & COAT OF ARMS For Immediate Release December 10, 2013 Niagara-on-the-Lake - Lord Mayor, accompanied by the Right Reverend D. Ralph Spence, Albion Herald Extraordinary, officially unveiled a new town flag and coat of arms today before an audience at the Courthouse. Following the official proclamation ceremony, a procession, led by the Fort George Fife & Drum Corps and completed by an honour guard from the 809 Newark Squadron Air Cadets, witnessed the raising of the flag. The procession then continued on to St. Mark’s Church for a special service commemorating the Burning of Niagara. “We thought this was a fitting date to introduce a symbol of hope and promise given the devastation that occurred exactly 200 years to the day, the burning of our town,” stated Lord Mayor Eke. “From ashes comes rebirth and hope.” The new flag, coat of arms and badge have been granted by the Chief Herald of Canada, Dr. Claire Boudreau, Director of the Canadian Heraldic Authority within the office of the Governor General. Bishop Spence, who served as Bishop of the Anglican Diocese of Niagara from 1998 - 2008, represented the Chief Herald and read the official proclamation. He is one of only four Canadians who hold the title of herald extraordinary. A description of the new coat of arms, flag and badge, known as armorial bearings in heraldry, is attached. For more information, please contact: Dave Eke, Lord Mayor 905-468-3266 Symbolism of the Armorial Bearings of The Corporation of the Town of Niagara-on-the-Lake Arms: The colours refer to the Royal Union Flag. -

Imagereal Capture

113 The Law of Arms in New Zealand: A Response Gregor Macaulay* :Noel Cox has written that "Ifany laws of arms were inherited by New Zealand, it 'was the Law of Arms of England, in 1840",1 and that in England and l'Jew Zealand today "the Law of Arms is the same in each jurisdiction",2 The statements cannot both be true; each is individually mistaken; and the English la~N of arms is in any case unworkable in New Zealand. In England, the laws of arms may be defined as the law governing "the use of anms, crests, supporters and other armorial insignia [which] is to be found in the customs and usages of the [English] Court ofChivalry",3 "augmented either by rulings of the [English] kings of arms or by warrants from the Earl Marshal [of England]".4 There are several standard reference books in English heraldry, but not even one revised and edited by a herald may, in his own words, be considered "authoritative in any official sense",5 and a definitive volume detailing the law of arms of England has never been published. A basic difficulty exists, therefore, in knowing precisely what the content of the law is that is being discussed. Even in England there are some extraordinary lacunae. For instance, the English heralds seem not to know who may legally inherit heraldic badges.6 If the English law of arms of 1840 had been inherited by New Zealand it would have come within the ambit of the English Laws Act 1858 (succeeded by the English Laws Act 1908). -

Royal Heraldry Society of Canada

The Toronto Branch of the Royal Heraldry Society of Canada Patron: Sir Conrad M.J.F. Swan , KCVO, PH.D, FSA, FRHSC ® Garter King of Arms Emeritus ® Volume 24, Issue 2 – JUNE 2014 ISSN: 1183-1766 WITHIN THE PAGES Royal Heraldry Society of Canada AGM OF THIS ISSUE: he weather After the business of the Finally, on Saturday evening could not Toronto Branch concluded, everyone came together International 2 have been Prof. Jonathan Good , PH.D, again at the Arts & Letters Heraldry Day T better in Toronto for the FRHSC spoke to those Club for a Gala affair, where Birds of a Feather 4 hosting of the 48th Annual members assembled, on the we were all witness to the In Memory General Meeting of the Royal topic of how universities in installation of two new 4 Slains Pursuivant Heraldry Society of Canada. Canada use there Coat of Fellows of the Society. Prof. The last weekend of May (30 Arms in branding their Steven Totosy spoke to the 9th Duke of 5 May—1 June), our Branch university. Each institution gathered group about Devonshire had the distinct honour of was classified based on the Hungarian Heraldry. hosting about 50 members of use of their coat of arms on Hungarian grants of Arms, Bits & Bites 6 the society. There was their website. Some used which are passed down representation from coast to their arms properly, some through sons and daughters, 2013 Grants of 7 coast. As well, some of our used a modified version, and follows a different set of Arms members from the United some did not use their arms rules and guidelines from the A Heraldic Artist States of America crossed at all. -

Arms and the (Tax-)Man: the Use and Taxation of Armorial Bearings in Britain, 1798–1944

Arms and the (tax-)man: The use and taxation of armorial bearings in Britain, 1798–1944. Philip Daniel Allfrey BA, BSc, MSc(Hons), DPhil. Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MLitt in Family and Local History at the University of Dundee. October 2016 Abstract From 1798 to 1944 the display of coats of arms in Great Britain was taxed. Since there were major changes to the role of heraldry in society in the same period, it is surprising that the records of the tax have gone unstudied. This dissertation evaluates whether the records of the tax can say something useful about heraldry in this period. The surviving records include information about individual taxpayers, statistics at national and local levels, and administrative papers. To properly interpret these records, it was necessary to develop a detailed understanding of the workings of the tax; the last history of the tax was published in 1885 and did not discuss in detail how the tax was collected. A preliminary analysis of the records of the armorial bearings tax leads to five conclusions: the financial or social elite were more likely to pay the tax; the people who paid the tax were concentrated in fashionable areas; there were differences between the types of people who paid the tax in rural and urban areas; women and clergy were present in greater numbers than one might expect; and the number of taxpayers grew rapidly in the middle of the nineteenth century, but dropped off after 1914. However, several questions have to be answered before -

English Catholic Heraldry Since Toleration, 1778–2010

THE COAT OF ARMS The journal of the Heraldry Society Fourth Series Volume I 2018 Number 235 in the original series started in 1952 Founding Editor † John P.B.Brooke-Little, C.V.O, M.A., F.H.S. Honorary Editor Dr Paul A Fox, M.A., F.S.A, F.H.S., F.R.C.P., A.I.H. Reviews Editor Tom O’Donnell, M.A., M.PHIL. Editorial Panel Dr Adrian Ailes, M.A., D.PHIL., F.S.A., F.H.S., A.I.H. Dr Jackson W Armstrong, B.A., M.PHIL., PH.D. Steven Ashley, F.S.A, a.i.h. Dr Claire Boudreau, PH.D., F.R.H.S.C., A.I.H., Chief Herald of Canada Prof D’Arcy J.D.Boulton, M.A., PH.D., D.PHIL., F.S.A., A.I.H. Dr Clive.E.A.Cheesman, M.A., PH.D., F.S.A., Richmond Herald Steen Clemmensen A.I.H. M. Peter D.O’Donoghue, M.A., F.S.A., York Herald Dr Andrew Gray, PH.D., F.H.S. Jun-Prof Dr Torsten Hiltmann, PH.D., a.i.h Prof Peter Kurrild-Klitgaard, PH.D., F.R.Hist.S., A.I.H. Elizabeth Roads, L.V.O., F.S.A., F.H.S., A.I.H, Snawdoun Herald Advertising Manager John J. Tunesi of Liongam, M.Sc., FSA Scot., Hon.F.H.S., Q.G. Guidance for authors will be found online at www.theheraldrysociety.com ENGLISH CATHOLIC HERALDRY SINCE TOLERATION, 1778–2010 J. A. HILTON, PH.D., F.R.Hist.S. -

A Lifetime Together

Between Us A Lifetime Together By Peter McKinnon he latest chapter in the Born Charles Emile Beddoe remarkable lives of Louise in Ottawa in 1920, Charlie has Tand Charlie Beddoe began enjoyed a storied life. As a seven earlier this year with a move into year-old, his father took him the Perley and Rideau Veterans’ to see Charles Lindberg, who Health Centre. Although they launched his international Spirit didn’t go far – their home was on of St. Louis tour in Ottawa. For the street immediately north of 25 cents, spectators could take a the Perley Rideau campus – it was short ride in a biplane – a double- their first move in 58 years. cockpit Avro Avian. Charlie still Louise Mona Fitzgerald remembers the thrill of flying arrived in the world in 1926 while seated on his father’s knee. in Quebec City. Like many in Alan Beddoe, Charlie’s father, her family, she worked in the served in World War I and was business founded by her maternal held in prisoner-of-war camps grandfather, Henry Ross. In the for more than two years. Alan’s 1890s, Ross employed residents wartime service inspired Charlie of a nearby First Nation band in to join the Royal Canadian Navy Charles Beddoe, the production of moccasins, Volunteer Reserve shortly after combat cameraman snowshoes and canoes. As a the outbreak of the Second young woman, Louise worked as World War. For the next five years, war effort.” bookkeeper. In the summer of Charlie travelled from Trinidad After his time at HQ, Charlie 1954, Louise was invited by an to Murmansk and served in a served as a gunner and ship’s aunt to visit her at her home in variety of roles, including Combat photographer aboard HMCS the Gatineau Hills. -

Introduction

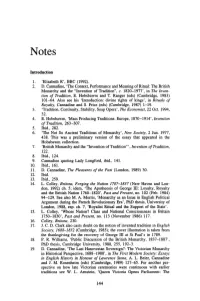

Notes Introduction 1. 'Elizabeth R·. BBC (1992). 2. D. Cannadine. 'The Context. Perfonnance and Meaning of Ritual: The British Monarchy and the "Invention of Tradition". c. 1820-1977'. in The Inven tion of Tradition. E. Hobsbawm and T. Ranger (eds) (Cambridge. 1983) 101-64. Also see his 'Introduction: divine rights of kings'. in Rituals of Royalty. Cannadine and S. Price (eds) (Cambridge. 1987) 1-19. 3. 'Tradition. Continuity. Stability. Soap Opera'. The Economist. 22 Oct. 1994. 32. 4. E. Hobsbawm. 'Mass Producing Traditions: Europe. 1870-1914'. Invention of Tradition. 263-307. 5. Ibid .• 282. 6. 'The Not So Ancient Traditions of Monarchy'. New Society. 2 Jun. 1977. 438. This was a preliminary version of the essay that appeared in the Hobsbawm collection. 7. 'British Monarchy and the "Invention of Tradition"'. Invention of Tradition. 122. 8. Ibid .• 124. 9. Cannadine quoting Lady Longford. ibid .• 141. 10. Ibid .• 161. 11. D. Cannadine. The Pleasures of the Past (London. 1989) 30. 12. Ibid. 13. Ibid .• 259. 14. L. Colley. Britons, Forging the Nation 1707-1837 (New Haven and Lon don. 1992) ch. 5; idem. 'The Apotheosis of George ill: Loyalty. Royalty and the British Nation 1760-1820'. Past and Present. no. 102 (Feb. 1984) 94-129. See also M. A. Morris. 'Monarchy as an Issue in English Political Argument during the French Revolutionary Era'. PhD thesis. University of London. 1988. esp. ch. 7. 'Royalist Ritual and the Support of the State'. 15. L. Colley. 'Whose Nation? Class and National Consciousness in Britain 1750-1830'. Past and Present. no. 113 (November 1986) 117. 16. -

Uot History Freidland.Pdf

Notes for The University of Toronto A History Martin L. Friedland UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London © University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2002 Toronto Buffalo London Printed in Canada ISBN 0-8020-8526-1 National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Friedland, M.L. (Martin Lawrence), 1932– Notes for The University of Toronto : a history ISBN 0-8020-8526-1 1. University of Toronto – History – Bibliography. I. Title. LE3.T52F75 2002 Suppl. 378.7139’541 C2002-900419-5 University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Humanities and Social Sciences Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the finacial support for its publishing activities of the Government of Canada, through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP). Contents CHAPTER 1 – 1826 – A CHARTER FOR KING’S COLLEGE ..... ............................................. 7 CHAPTER 2 – 1842 – LAYING THE CORNERSTONE ..... ..................................................... 13 CHAPTER 3 – 1849 – THE CREATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO AND TRINITY COLLEGE ............................................................................................... 19 CHAPTER 4 – 1850 – STARTING OVER ..... .......................................................................... -

November 2019 BCA’S Holiday

Blackburn Area News and Reports ANAR Vol. 53 No. 2 B November 2019 BCA’s Holiday Pancake Breakfast Saturday, December 7th 8:30 am to 11:30 am Come and enjoy pancakes, crafts and get your photo with a Special Guest! Tickets: $5/Child, $8/Adult Free admission for BCA Members* *$10 household membership will be available for purchase on site. All funds raised will support initiatives right here in Blackburn Hamlet! For more information, visit BlackburnHamlet.ca or contact by email at [email protected] 2 • The BANAR November 2019 President’s message I would like to take this opportunity to thank all of the volunteers that make the Hamlet a great place to live in and to be a part of the best community in Ottawa. The perfect example is that once again the team of co-chairs Lee 5 FUNFAIR wrap-up & Sponsors Stach and Don Kelly and all their volunteers organized another 7 Cancer Chase wrap-up amazing Cancer Chase. Participation was at an all time high and I 8 Cancer Chase Sponsors can't say how proud I am of the whole team. 8 Free Family Skate Dec 15 The next activity your board is working on is Santa's Pancake 9 Councillor’s Message - Option 7 Breakfast on December 7th. Once again we will have a delicious 11 The Beddoe War Veterans pancake breakfast with fixings served throughout the morning with 13 BANAR 2019 Advertisers Santa arriving about 30 or so minutes in. Getting a picture with 15 Blackburn Tennis—Thank you Santa, doing some fun crafts and a host of other activities will make 15 Norman Johnson planting garden for a fun time for all ages.