The Law of Prior Appropriation: Possible Lessons for Hawaii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bundle of S Cks—Real Property Rights and Title Insurance Coverage

Bundle of Scks—Real Property Rights and Title Insurance Coverage Marc Israel, Esq. What Does Title Insurance “Insure”? • Title is Vested in Named Insured • Title is Free of Liens and Encumbrances • Title is Marketable • Full Legal Use and Access to Property Real Property Defined All land, structures, fixtures, anything growing on the land, and all interests in the property, which may include the right to future ownership (remainder), right to occupy for a period of +me (tenancy or life estate), the right to build up (airspace) and drill down (minerals), the right to get the property back (reversion), or an easement across another's property.” Bundle of Scks—Start with Fee Simple Absolute • Fee Simple Absolute • The Greatest Possible Rights Insured by ALTA 2006 Policy • “The greatest possible estate in land, wherein the owner has the right to use it, exclusively possess it, improve it, dispose of it by deed or will, and take its fruits.” Fee Simple—Lots of Rights • Includes Right to: • Occupy (ALTA 2006) • Use (ALTA 2006) • Lease (Schedule B-Rights of Tenants) • Mortgage (Schedule B-Mortgage) • Subdivide (Subject to Zoning—Insurable in Certain States) • Create a Covenant Running with the Land (Schedule B) • Dispose Life Estate S+ck • Life Estate to Person to Occupy for His Life+me • Life Estate can be Conveyed but Only for the Original Grantee’s Lifeme • Remainderman—Defined in Deed • Right of Reversion—Defined in Deed S+cks Above, On and Below the Ground • Subsurface Rights • Drilling, Removing Minerals • Grazing Rights • Air Rights (Not Development Rights—TDRs) • Canlever Over a Property • Subject to FAA Rules NYC Air Rights –Actually Development Rights • Development Rights are not Real Property • Purely Statutory Rights • Transferrable Development Rights (TDRs) Under the NYC Zoning Resoluon and Department of Buildings Rules • Not Insurable as They are Not Real Property Title Insurance on NYC “Air Rights” • Easement is an Insurable Real Property Interest • Easement for Light and Air Gives the Owner of the Merged Lots Ability to Insure. -

Common Ways to Hold Title

Common Ways to Hold Title HOW YOU TAKE TITLE - ADVANTAGES AND LIMITATIONS: Title to real property may be held by individuals, either in Sole Ownership or in Co-Ownership. Co-Ownership of real property occurs when title is held by two or more persons. There are several variations as to how title may be held in each type of ownership. The following brief summaries reference seven of the more common examples of Sole Ownership and Co-Ownership. SOLE OWNERSHIP A man or woman who is not married. Example: John Doe, a single man. An Unmarried Man/Woman: A man or woman, who having been married, is legally divorced. Example: John Doe, an unmarried man. A Married Man/Woman, as His/Her Sole and Separate Property: When a married man or woman wishes to acquire title as their sole and separate property, the spouse must consent and relinquish all right, title and interest in the property by deed or other written agreement. Example: John Doe, a married man, as his sole and separate property. CO-OWNERSHIP Community Property: Property acquired by husband and wife, or either during marriage, other than by gift, bequest, devise, descent or as the separate property of either is presumed community property. Example: John Doe and Mary Doe, husband and wife, as community property. Example: John Doe and Mary Doe, husband and wife. Example: John Doe, a married man Joint Tenancy: Joint and equal interests in land owned by two or more individuals created under a single instrument with right of survivorship. Example: John Doe and Mary Doe, husband and wife, as joint tenants. -

Common Ways of Holding Title to Real Property

NORTH AMERICAN TITLE COMPANY Common Ways of Holding Title to Real Property Tenancy in Common Joint Tenancy Parties Any number of persons. Any number of persons. (Can be husband and wife) (Can be husband and wife) Division Ownership can be divided into any number of Ownership interests cannot be divided. interests, equal or unequal. Title Each co-owner has a separate legal title to his There is only one title to the entire property. undivided interest. Possession Equal right of possession. Equal right of possession. Conveyance Each co-owner’s interest may be conveyed Conveyance by one co-owner without the separately by its owner. others breaks the joint tenancy. Purchaser’s Status Purchaser becomes a tenant in common with Purchaser becomes a tenant in common with other co-owners. other co-owners. Death On co-owner’s death, his interest passes by On co-owner’s death, his interest ends and will or intestate succession to his devisees or cannot be willed. Surviving joint tenants heirs. No survivorship right. own the property by survivorship. Successor’s Status Devisees or heirs become tenants in common. Last survivor owns property in severalty. Creditor’s Rights Co-owner’s interest may be sold on execution Co-owner’s interest may be sold on execu- sale to satisfy his creditor. Creditor becomes a tion sale to satisfy creditor. Joint tenancy is tenant in common. broken, creditor becomes tenant in common. Presumption Favored in doubtful cases. None. Must be expressly declared. This is provided for informational puposes only. Specific questions for actual real property transactions should be directed to your attorney or C.P.A. -

The Dual-System of Water Rights in Nebraska George Rozmarin University of Nebraska College of Law

Nebraska Law Review Volume 48 | Issue 2 Article 6 1968 The Dual-System of Water Rights in Nebraska George Rozmarin University of Nebraska College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr Recommended Citation George Rozmarin, The Dual-System of Water Rights in Nebraska, 48 Neb. L. Rev. 488 (1969) Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr/vol48/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 488 NEBRASKA LAW REVIEW-VOL. 48, NO. 2 (1969) Co'mment THE DUAL-SYSTEM OF WATER RIGHTS IN NEBRASKA I. INTRODUCTION In Nebraska, rights to waters in streams and lakes have been regulated through a dual-system which utilizes both the riparian doctrine of the common law and the statutory scheme of appropri- ative rights. Although the two doctrines are divergent in many instances, the judiciary has recognized this and attempted to main- tain a balance between them. Despite these efforts, however, inconsistent principles of law developed over the years until finally in Wasserburgerv. Coffee1 the Nebraska Supreme Court attempted to reconcile the relative status of riparians and appropriators. In doing so the court prescribed a flexible method of equitable balance rather than a static formula of distribution. This article will give a brief introduction to some of the problems faced in distributing water rights under this dual-system, and will attempt to determine what effect Wasserburger may have on these rights that are so intimately linked with the prosperity of the state and Eill of its citizens. -

Real & Personal Property

CHAPTER 5 Real Property and Personal Property CHRIS MARES (Appleton, Wsconsn) hen you describe property in legal terms, there are two types of property. The two types of property Ware known as real property and personal property. Real property is generally described as land and buildings. These are things that are immovable. You are not able to just pick them up and take them with you as you travel. The definition of real property includes the land, improvements on the land, the surface, whatever is beneath the surface, and the area above the surface. Improvements are such things as buildings, houses, and structures. These are more permanent things. The surface includes landscape, shrubs, trees, and plantings. Whatever is beneath the surface includes the soil, along with any minerals, oil, gas, and gold that may be in the soil. The area above the surface is the air and sky above the land. In short, the definition of real property includes the earth, sky, and the structures upon the land. In addition, real property includes ownership or rights you may have for easements and right-of-ways. This may be for a driveway shared between you and your neighbor. It may be the right to travel over a part of another person’s land to get to your property. Another example may be where you and your neighbor share a well to provide water to each of your individual homes. Your real property has a formal title which represents and reflects your ownership of the real property. The title ownership may be in the form of a warranty deed, quit claim deed, title insurance policy, or an abstract of title. -

Vehicle Use Tax and Calculator Questions and Answers

Arizona Department of Revenue Vehicle Use Tax and Calculator Questions and Answers April 2020 If you recently purchased a vehicle from an out-of-state A. No. Because the online dealer is an Arizona business, dealer and plan to register it in Arizona, you may owe use the dealer is responsible for the tax due on the sale of tax. Below are questions and answers to provide guidance the vehicle. The dealer should report and remit TPT about use tax and the Vehicle Use Tax Calculator. to Arizona Department of Revenue (ADOR). You do For general information about Use Tax, please refer not owe use tax on the purchase even if the bill of to Publication 610A - Use Tax for Individual Income sale does not show an itemized tax amount. Arizona Taxpayers on the ADOR website. Revised Statutes (A.R.S.) § 42-5155(F). To calculate the amount of use tax you owe on your out-of- Q. I purchased my vehicle from a private party. Do I state vehicle purchase, use the Vehicle Use Tax Calculator owe use tax? on our website at www.azdor.gov, under “E-Services.” A. No. Casual sales between private parties are not taxable. When you register your vehicle at MVD, bring Q. What is use tax? a copy of the bill of sale or any documentation that A. Use tax is imposed on the “storage, use or consumption shows you purchased the vehicle from a private party. in Arizona” of tangible personal property (such as a car) that is purchased from a retailer. -

Effects of Title Ownership on Property

Title and or physical possession is the manner in Effects of Title which both real and personal property is owned. Ownership on Title may come in the form of deed, certificate, bill of sale, contract or some other document. Property These pieces of paper designating title are important designations that cannot be separated Author: Carolyn Paseneaux from a will. 307-778-0040 [email protected] Forms of Property Ownership Sole ownership of property is the simplest and Until substantial amounts of property are gives the holder the most complete ownership acquired, few focus on estate planning. However, possible. When the property is transferred, there the method by which titles are held to land, is a minimum of red tape since the titleholder livestock, machinery and other property can have has the right to dispose of the property. During important estate planning implications. When, the titleholder’s life there are laws of the state late in life, it is decided to plan an estate, making that dictate how the property is to be managed. changes in title ownership can create problems You cannot infringe on the rights of a neighbor, such as gift taxes. zoning restrictions dictate whether an agriculture operation is allowed in certain areas, and you Deciding on ownership is generally based on cannot disregard the interest rights of a surviving the following five factors: Preference as to sole spouse. Wyoming is a common law state and ownership or co-ownership (joint tenancy and thus protects spouses and keeps them from tenancy in common); desired disposition of being left out in the cold when the other spouse property at death; estate and inheritance tax dies. -

Property; Title by Prescription; Repealer; Effective Date

STATE OF OKLAHOMA 1st Session of the 49th Legislature (2003) HOUSE BILL HB1584 By: Nations AS INTRODUCED An Act relating to property; amending 60 O.S. 2001, Section 333, which relates to title by prescription; providing method of acquiring title to real property by prescription; providing requirements necessary to establish title by lawsuit; providing applicability to boundary disputes; providing limitations to certain actions; and providing an effective date. BE IT ENACTED BY THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF OKLAHOMA: SECTION 1. AMENDATORY 60 O.S. 2001, Section 333, is amended to read as follows: Section 333. A. Occupancy for the period prescribed by civil procedure and pursuant to the provisions of this section, or any law of this state as sufficient to bar an action for the recovery of the property, confers a title thereto, denominated a title by prescription, which is sufficient against all. B. For the purpose of constituting title by prescription by a person claiming title not founded upon a written and recorded instrument or by judgment or decree, the land is deemed to have been possessed and occupied only: 1. Where it has been protected by a substantial enclosure and usually cultivated or improved; or 2. Where, though not enclosed, it has been used and occupied so openly and notoriously as to attract the attention of every other claimant, and so exclusively as to prevent actual occupation by another. Title by prescription may be conferred only to that land so actually possessed and occupied. Req. No. 5100 Page 1 C. For the purpose of constituting title by prescription by a person claiming good faith title founded upon a written and recorded instrument or by a judgment or decree, the land is deemed to have been possessed and occupied only: 1. -

Page 140 TITLE 18—CRIMES and CRIMINAL PROCEDURE § 641

§ 641 TITLE 18—CRIMES AND CRIMINAL PROCEDURE Page 140 § 101(d)(1)–(3), (4)(A), (e)(3), Oct. 15, 1974, 88 Stat. 1267, AMENDMENTS prohibited campaign contributions by foreign nation- 1996—Pub. L. 104–294, title VI, § 601(f)(7), Oct. 11, 1996, als. See section 441e of Title 2, The Congress. 110 Stat. 3500, inserted comma after ‘‘embezzlement’’ in Section 614, added Pub. L. 93–443, title I, § 101(f)(1), item 656. Oct. 15, 1974, 88 Stat. 1268, prohibited making of cam- Pub. L. 104–191, title II, § 243(b), Aug. 21, 1996, 110 Stat. paign contributions in the name of another. See section 2017, added item 669. 441f of Title 2, The Congress. 1994—Pub. L. 103–322, title XXXII, § 320902(d)(1), Sept. Section 615, added Pub. L. 93–443, title I, § 101(f)(1), 13, 1994, 108 Stat. 2124, added item 668. Oct. 15, 1974, 88 Stat. 1268, placed limitations on con- 1984—Pub. L. 98–473, title II, §§ 1104(b), 1112, Oct. 12, tributions of currency. See section 441g of Title 2, The 1984, 98 Stat. 2144, 2149, added items 666 and 667. Congress. Section 616, added Pub. L. 93–443, title I, § 101(f)(1), 1978—Pub. L. 95–524, § 3(b), Oct. 27, 1978, 92 Stat. 2018, Oct. 15, 1974, 88 Stat. 1268, prohibited acceptance of ex- substituted ‘‘employment and training funds’’ for cessive honorariums. See section 441i of Title 2, The ‘‘manpower funds’’ and inserted ‘‘; obstruction of inves- Congress. tigations’’ after ‘‘improper inducement’’ in item 665. Section 617, added Pub. L. -

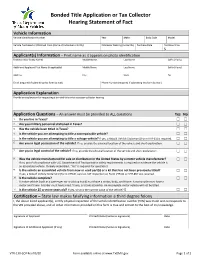

Form VTR-130-SOF

Bonded Title Application or Tax Collector Hearing Statement of Fact Vehicle Information Vehicle Identification Number Year Make Body Style Model Vehicle Purchased or Obtained From (Name of Individual or Entity) Odometer Reading (no tenths) Purchase Date Purchase Price $ Applicant(s) Information – Print name as it appears on photo identification First Name (or Entity Name) Middle Name Last Name Suffix (if any) Additional Applicant First Name (if applicable) Middle Name Last Name Suffix (if any) Address City State Zip Email (required if submitting this form by mail) Phone Number (required if submitting this form by mail) Application Explanation Provide an explanation for requesting a bonded title or tax assessor-collector hearing. Application Questions – An answer must be provided to ALL questions Yes No 1. Do you live in Texas? ☐ ☐ 2. Are you military personnel stationed in Texas? ☐ ☐ 3. Has the vehicle been titled in Texas? ☐ ☐ 4. Is the vehicle you are attempting to title a nonrepairable vehicle? ☐ ☐ 5. Is the vehicle you are attempting to title a salvage vehicle? If yes, a Rebuilt Vehicle Statement (Form VTR-61) is required. ☐ ☐ 6. Are you in legal possession of the vehicle? If no, provide the physical location of the vehicle and short explanation. ☐ ☐ 7. Are you in legal control of the vehicle? If no, provide the physical location of the vehicle and short explanation. ☐ ☐ 8. Was the vehicle manufactured for sale or distribution in the United States by a motor vehicle manufacturer? ☐ ☐ If no, proof of compliance with U.S. Department of Transportation safety requirements is required or evidence the vehicle is an assembled vehicle. -

The Myth of Title Theft What Providers of “Protection” Against It Aren’T Telling You

INSIGHTS LEGAL AFFAIRS The myth of title theft What providers of “protection” against it aren’t telling you itle theft” was a term unknown just a generation ago. Now WILLIAM J. MAFFUCCI Attorney advertisers bombard us “T Semanoff Ormsby Greenberg & Torchia, LLC daily with warnings about it. They say that thieves can “steal” our homes by (267) 620-1901 forging our names on deeds, then resell [email protected] the property or take out mortgage loans to drain its equity. They pocket Insights Legal Affairs is brought to you by Semanoff Ormsby Greenberg & Torchia, LLC the proceeds and “stick” us with any mortgage payments. But can a thief really “steal” your lengthy, involving expert testimony as the provider will prepare and file in the house through forgery, and are you to the validity of the signatures, and land records document to alert further really obligated to pay off a thief’s prohibitively expensive. buyers or lenders that the instrument mortgage loan? Although the owner has no legal was forged. Smart Business spoke with William obligation to repay the forger’s loan, the Owners can check the land records Maffucci, a real-estate litigator with owner may ultimately feel constrained to on their own, but there’s value to the Semanoff Ormsby Greenberg & do so as a practical matter. Some owners convenience of having someone regularly Torchia, LLC, to find out. don’t learn of the forged mortgage check the land records for them. There’s until the lender moves to foreclose the also a value to having a ‘red flag’ affidavit Can someone acquire title to a real mortgage, or even after the foreclosure prepared and recorded as to any forged property simply by forging the owner’s process is complete and title has passed deed that is discovered — but only if name on a deed? again. -

Real Estate Dictionary

REAL ESTATE DICTIONARY This dictionary serves as a reference tool for individuals and organizations in the real estate community. We hope you find useful its brief definitions of real estate-related terminology. We welcome the opportunity to be of service to you. A Adverse Possession: A claim made against the land of another by virtue of open and notorious possession Abstract of Title: A condensed history or summary of of said land by the claimant. all transactions affecting a particular tract of land. Affidavit: A sworn statement in writing. Access: The legal right to enter and leave a tract of land from a public way. Can include the right to enter and Agent: A person or company that has the power to leave over the land of another. act on behalf of another or to transact business for another, e.g., a title agent under contract with Old Accretion: The slow buildup of land by natural forces Republic Title is an agent solely for the purpose such as wind or water. of issuing policies of title insurance and other title insurance products. Adjustable Rate Mortgage (ARM): A residential mortgage that has an interest rate that is subject to Air Rights: The right to ownership of everything above change. The times of adjustment are agreed upon at the physical surface of the land. the inception of the loan. ALTA: American Land Title Association, a national Administrator: A person appointed by a probate court association of title insurance companies, abstractors to settle the affairs of an individual dying without a and attorneys specializing in real property law.