Archaeological Investigations in the Takla Lake Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rock Art Studies: a Bibliographic Database Page 1 800 Citations: Compiled by Leigh Marymor 04/12/17

Rock Art Studies: A Bibliographic Database Page 1 800 Citations: Compiled by Leigh Marymor 04/12/17 Keywords: Peterborough, Canada. North America. Cultural Adams, Amanda Shea resource management. Conservation and preservation. 2003 Reprinted from "Measurement in Physical Geography", Visions Cast on Stone: A Stylistic Analysis of the Occasional Paper No. 3, Dept. of Geography, Trent Petroglyphs of Gabriola Island, BCMaster/s Thesis :79 pgs, University, 1974. Weathering. University of British Columbia. Cited from: LMRAA, WELLM, BCSRA. Keywords: Gabriola Island, British Columbia, Canada. North America. Stylistic analysis. Marpole Culture. Vision. Alberta Recreation and Parks Abstract: "This study explores the stylistic variability and n.d. underlying cohesion of the petroglyphs sites located on Writing-On-Stone Provincial ParkTourist Brochure, Alberta Gabriola Island, British Columbia, a southern Gulf Island in Recreation and Parks. the Gulf of Georgia region of the Northwest Coast (North America). I view the petroglyphs as an inter-related body of Keywords: WRITING-ON-STONE PROVINCIAL PARK, ancient imagery and deliberately move away from (historical ALBERTA, CANADA. North America. "THE BATTLE and widespread) attempts at large regional syntheses of 'rock SCENE" PETROGLYPH SITE INSERT INCLUDED WITH art' and towards a study of smaller and more precise PAMPHLET. proportion. In this thesis, I propose that the majority of petroglyphs located on Gabriola Island were made in a short Cited from: RCSL. period of time, perhaps over the course of a single life (if a single, prolific specialist were responsible for most of the Allen, W.A. imagery) or, at most, over the course of a few generations 2007 (maybe a family of trained carvers). -

Carrier Sekani Tribal Council Aboriginal Interests & Use Study On

Carrier Sekani Tribal Council Aboriginal Interests & Use Study on the Enbridge Gateway Pipeline An Assessment of the Impacts of the Proposed Enbridge Gateway Pipeline on the Carrier Sekani First Nations May 2006 Carrier Sekani Tribal Council i Aboriginal Interests & Use Study on the Proposed Gateway Pipeline ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Carrier Sekani Tribal Council Aboriginal Interests & Use Study was carried out under the direction of, and by many members of the Carrier Sekani First Nations. This work was possible because of the many people who have over the years established the written records of the history, territories, and governance of the Carrier Sekani. Without this foundation, this study would have been difficult if not impossible. This study involved many community members in various capacities including: Community Coordinators/Liaisons Ryan Tibbetts, Burns Lake Band Bev Ketlo, Nadleh Whut’en First Nation Sara Sam, Nak’azdli First Nation Rosa McIntosh, Saik’uz First Nation Bev Bird & Ron Winser, Tl’azt’en Nation Michael Teegee & Terry Teegee, Takla Lake First Nation Viola Turner, Wet’suwet’en First Nation Elders, Trapline & Keyoh Holders Interviewed Dick A’huille, Nak’azdli First Nation Moise and Mary Antwoine, Saik’uz First Nation George George, Sr. Nadleh Whut’en First Nation Rita George, Wet’suwet’en First Nation Patrick Isaac, Wet’suwet’en First Nation Peter John, Burns Lake Band Alma Larson, Wet’suwet’en First Nation Betsy and Carl Leon, Nak’azdli First Nation Bernadette McQuarry, Nadleh Whut’en First Nation Aileen Prince, Nak’azdli First Nation Donald Prince, Nak’azdli First Nation Guy Prince, Nak’azdli First Nation Vince Prince, Nak’azdli First Nation Kenny Sam, Burns Lake Band Lillian Sam, Nak’azdli First Nation Ruth Tibbetts, Burns Lake Band Ryan Tibbetts, Burns Lake Band Joseph Tom, Wet’suwet’en First Nation Translation services provided by Lillian Morris, Wet’suwet’en First Nation. -

Fort St. James Guide

Table of Contents Welcome Message ................... 3 Parks ............................... 10 Getting Here ........................ 6 Seasonal Activities ................... 11 Getting Around Town ................. 7 Remote Wildlife Experiences. 14 Unique to Fort St. James .............. 8 Trails ............................... 18 History ............................. 24 2 Welcome Message On the scenic shore of beautiful Stuart Lake is a community both historic and resourceful! Fort St. James offers an abundance of year-round recreational activities including hunting, fishing, trails for biking, hiking, motor sports, water sports, marina, and snow and ice sports. Established by Simon Fraser in 1806, the Fort St. James area is rich with historical significance. The geographically close communities of Fort St. James, Nak’azdli, Tl’azt’en and Yekooche First Nations played an integral role in developing the north. Beginning with the fur trade and building strong economies on forestry, mining, energy and tourism; Fort St. James is a resourceful place! It is also independent business friendly, providing resources and supports Fort St. James provides a safe and healthy community for entrepreneurs even being formally for families and gainful employment opportunities. recognized with a provincial “open for A College of New Caledonia campus, accompanied business” award. by three elementary schools and a high school keeps Fort St. James is a service centre for rural our innovative community engaged and educated. communities offering stores, restaurants, In addition to education, health is a priority with banking, accommodations and government our Stuart Lake Hospital and Medical Clinic and offices. Uniquely this town boasts an array of community hall for recreation. volunteer-driven organizations and services Whether you visit for the history or stay for the including a ski hill, golf course, theatre and resources, Fort St. -

Download Download

The Ethno-Genesis of the Mixed-Ancestry Population in New Caledonia Duane Thomson n British Columbia and elsewhere in Canada the question of which mixed-ancestry persons qualify for Métis status is a largely unresolved public policy issue. Whether this issue is eventually Idecided by legal decisions or by political accommodation, the historical background relating to British Columbia’s mixed-ancestry population is an important element in the discussion and requires detailed exploration. Historical research conducted for the Department of Justice forms the basis of this study of the ethno-genesis of the mixed-ancestry population of central British Columbia.1 To understand the parameters of this research, some background regarding the 2003 R. v. Powley decision in the Supreme Court of Canada is necessary. The Court ruled that Steve and Roddy Powley, two mixed-ancestry men from Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, qualified for Métis status. They thus enjoyed a constitutionally protected right to hunt for food under s. 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.2 In its decision, the Court also set out the criteria that succeeding mixed-ancestry applicants must meet to similarly qualify for Métis status. One important criterion was that Métis Aboriginal rights rest in the existence of a historic, self- 1 For a summary of some of these legal and political issues, see Jean Barman and Mike Evans, “Reflections on Being, and Becoming, Métis in British Columbia,” BC Studies 161 (Spring 2009): 59-91. New Caledonia is the region chosen by Barman and Evans in their attempt to show that a Métis community developed in British Columbia. -

C-13 Aboriginal Groups

Pine River 127°0'0"W 126°0'0"W 125°0'0"W 124°0'0"W 123°0'0"W 122°0'0"W W i l l Mackenzie i s Mount Blanchet Park (PP) t Gwillim Lake Park (PP) o n e Pine Lemoray Park (PP) k Nation River L tlo La chen a T k Chuchi Lake e N B 39 29 " a bin e Lake r 0 e owit e ' L Nat v ake T e i 0 a k ak R ° L la tch y 5 i a L W r 5 a r k u e M T o c h Babine Mountains Park (PP) c h M a id d KP 560.6 L le INZANA LAKE 12 a R B r i t i s h C o l u m b i a k i e v Inza er na La F ke N u " lto n 0 Smithers La ' ke 0 ° 5 5 ke La ur ble Babine Lake em Telkwa Tr P r B a ve u rs Hook Lake Tumbler Ridge i lk Carp Lake n R le ip KP 600 wa y Pump Station lk R Te R Te i z iv v ze e er Rubyrock Lake Park (PP) r r on Carp Lake Park (PP) KP 620 N L or a th k N A e KP 630 " rm KP 610 0 ' 0 3 Nak'azdli Band ° Perow 4 KP 640 5 P Topley inc hi L KP 1077.3 16 ake KP 670 KP 660 Stuart Lake STUART LAKE 10 97 KP 680 KP 650 STUART LAKE 9 CARRIER LAKE 15 Bear Lake KP 690 Monkman Park (PP) Houston Sutherland River Park (PP) Fort St. -

Of the Babine River I I an Historical Perspective

I I Scientific Excellence • Resource Protection & Conservation • Benefits for Canadians Excellence scientifique • Protection et conservation des ressources • Bénéfices aux Canadiens I a _° IIIII 'ïWiiuWï r". 12020078 I ÎN Al 11 D NON-NATIVE USE OF THE BABINE RIVER I I AN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE 1 by Brendan O'Donnell 1 Native Affairs Division Issue 2 1 Policy and Program Planning I I I I I 1#1 Fisheries Pêches and Oceans et Océans Canad1a I INTRODUCTION The following is one of a series of reports on the historicai uses of waterways in New Brunswick and British Columbia. These reports are narrative outlines of how Indian and non-native populations have used these .rivers, with emphasis on navigability, tidal influence, riparian interests, settlement patterns, commercial use and fishing rights. These historical reports were requested by the Interdepartmental Reserve Boundary Review Committee, a body comprising representatives from Indian Affairs and Northern Development [DIAND], Justice, Energy, Mines and Resources [EMR], and chaired by Fisheries and Oceans. The committee is tasked with establishing a government position on reserve boundaries that can assist in determining the area of application of Indian Band fishing by-laws. Although each report in this series is as different as the waterway it describes, there is a common structural approach to each paper. Each report describes the establishment of Indian eserves along the river; what Licences of Occupation were issued; what instructions were given to surveyors laying out these reserves; how each surveyor laid out each reserve based on his field notes and survey plan; what, if any, fishing rights were considered for the Indian Bands; and how the Indian and non-native populations have used the waterway over the past centuries for both commercial and recreational use. -

Duncan Lake): a Draft Report

Tse Keh Nay Traditional and Contemporary Use and Occupation at Amazay (Duncan Lake): A Draft Report Amazay Lake Photo by Patrice Halley Draft Submission to the Kemess North Joint Review Panel May, 2007 Report Prepared By: Loraine Littlefield Linda Dorricott Deidre Cullon With Contributions By: Jessica Place Pam Tobin On Behalf of the Tse Keh Nay ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was written under the direction of the Tse Keh Nay leaders. The authors would like to thank Grand Chief Gordon Pierre and Chief Johnny Pierre of the Tsay Keh Dene First Nation; Chief John Allen French of the Takla Lake First Nation and Chief Donny Van Somer of the Kwadacha First Nation for their support and guidance throughout this project. The authors are particularly indebted to the advisors for this report who took the time to meet with us on very short notice and who generously shared with us their knowledge of Tse Keh Nay history, land and culture. We hope that this report accurately reflects this knowledge. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Grand Chief Gordon Pierre, Ray Izony, Bill Poole, Trevor Tomah, Jean Isaac, Robert Tomah, Chief John Allen French, Josephine West, Frank Williams, Cecilia Williams, Lillian Johnny, Hilda George and Fred Patrick. We would also like to thank the staff at the Prince George band and treaty offices for assembling and providing us with the documents, reports, maps and other materials that were used in this report. J.P. Laplante, Michelle Lochhead, Karl Sturmanis, Kathaleigh George, and Henry Joseph all provided valuable assistance and support to the project. -

REPORT on the Status of Bc First Nations Languages

report on the status of B.C. First Nations Languages Third Edition, 2018 Nłeʔkepmxcín Sgüüx̣s Danezāgé’ Éy7á7juuthem diitiidʔaatx̣ Gitsenimx̱ St̓át̓imcets Dane-Zaa (ᑕᓀ ᖚ) Hul’q’umi’num’ / Halq’eméylem / hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ Háiɫzaqvḷa Nisg̱a’a Sk̲wx̱wú7mesh sníchim Nsyilxcən Dakelh (ᑕᗸᒡ) Kwak̓wala Dene K’e Anishnaubemowin SENĆOŦEN / Malchosen / Lekwungen / Semiahmoo/ T’Sou-ke Witsuwit'en / Nedut'en X̄enaksialak̓ala / X̄a’islak̓ala Tāłtān X̱aad Kil / X̱aaydaa Kil Tsilhqot'in Oowekyala / ’Uik̓ala She shashishalhem Southern Tutchone Sm̓algya̱x Ktunaxa Secwepemctsín Łingít Nuučaan̓uɫ ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐍᐏᐣ (Nēhiyawēwin) Nuxalk Tse’khene Authors The First Peoples’ Cultural Council serves: Britt Dunlop, Suzanne Gessner, Tracey Herbert • 203 B.C. First Nations & Aliana Parker • 34 languages and more than 90 dialects • First Nations arts and culture organizations Design: Backyard Creative • Indigenous artists • Indigenous education organizations Copyediting: Lauri Seidlitz Cover Art The First Peoples’ Cultural Council has received funding Janine Lott, Title: Okanagan Summer Bounty from the following sources: A celebration of our history, traditions, lands, lake, mountains, sunny skies and all life forms sustained within. Pictographic designs are nestled over a map of our traditional territory. Janine Lott is a syilx Okanagan Elder residing in her home community of Westbank, B.C. She works mainly with hardshell gourds grown in her garden located in the Okanagan Valley. Janine carves, pyro-engraves, paints, sculpts and shapes gourds into artistic creations. She also does multi-media and acrylic artwork on canvas and Aboriginal Neighbours, Anglican Diocese of British wood including block printing. Her work can be found at Columbia, B.C. Arts Council, Canada Council for the Arts, janinelottstudio.com and on Facebook. Department of Canadian Heritage, First Nations Health Authority, First Peoples’ Cultural Foundation, Margaret A. -

Department of Mines and Resources Geology And

CANADA DEPARTMENT OF MINES AND RESOURCES MINES AND GEOLOGY BRANCH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN No. 5 GEOLOGY AND MINERAL DEPOSITS OF NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA WEST OF THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS BY J. E. Armstrong OTTAWA EDMOND CLOUTIER PRINTER TO THE KING'S MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY 1946 Price, 25 cents CANADA DEPARTMENT OF MINES AND RESOURCES MINES AND GEOLOGY BRANCH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN No. 5 GEOLOGY AND MINERAL DEPOSITS OF NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA WEST OF THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS BY J. E. Armstrong OTTAWA EDMOND CLOUTIER PRINTER TO THE KING'S MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY 1946 Price, 25 cents CONTENTS Page Preface............ .................... .......................... ...... ........................................................ .... .. ........... v Introduction........... h····················································· ···············.- ··············· ·· ········ ··· ··················· 1 Physiography. .............. .. ............ ... ......................... ·... ............. ....................... .......................... .... 3 General geology.. ........ ....................................................................... .... .. ... ...... ....... .. .... .... .. .. .. 6 Precambr ian........................................................................................... .... .. ....................... 6 Palreozoic................ .. .... .. .. ....... ................. ... ... ...... ................ ......... .... ... ... ...... .. .. .. ... .. .... ....... 7 Mesozoic.......................... .......... .................................................... -

° FO Lilll/L~~Ll~Lil~Lf I~ Lil~Illii~Lrque

°FO lilll/l~~ll~li l l~lfI~ lil~illii~lrque 12001752 S~ON QUALITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR FISHERIES MANAGEMENT , ,. :·1 · ~ :: ·, ~ ~ .. :~ by A. Wayne Holmes Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Field Services Branch Victoria, B. C. "1".i ~ -. •' { • ... ~ ... _. ... _·:_· ! > "•• r) ~ . April, 1982 SH 167 . .S l 7 H66 D c . oi. 'I -I ) (,- / I , LI I \ ' THE LIBRARY BEDFORD INSTITUTI! OP: OCEANOGRAPHY BOX 1006 DARTMOUTH, N.S. B2Y 4A2 SAUfON QUALITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR FISHERIES MANAGEMENT UBRARY FISHERIES AND OCEANS BlBUOTHEQUE PECHES ET OCEANS by .,, \ A. Wayne Holmes Department of Fisheries and Oceans, • L Field Services Branch Victoria, B.C. April, 1982 TABLE OF CONTENTS i. ABSTRACT .............................................. 0 •••••••••••••••••• iii. LIST OF TABLES .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. iv • LIST OF FIGURES • • • • • 0 ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• iv • PURPOSE .................................................................. 1 BACKGROUND ............................................................... 1 FACTORS ..................................... ct •••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 3 A. SALtfON QUALITY ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••.•• 3 1 • Grades .................................................... 3 2. Maturity by Species ...................................... 4 3. Spoilage Factors .......................................... 9 B. FISHERIES MANAGEMENT FOR QUALITY ............................... 11 1. Salmon Canned in 1981 11 2. Information on Stocks at Various Geographical Locations 28 c. PARASITES -

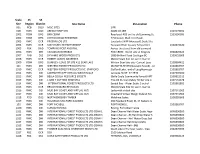

Scale Site SS Region SS District Site Name SS Location Phone

Scale SS SS Site Region District Site Name SS Location Phone 001 RCB DQU MISC SITES SIFR 01B RWC DQC ABFAM TEMP SITE SAME AS 1BB 2505574201 1001 ROM DPG BKB CEDAR Road past 4G3 on the old Lamming Ce 2505690096 1002 ROM DPG JOHN DUNCAN RESIDENCE 7750 Lower Mud river Road. 1003 RWC DCR PROBYN LOG LTD. Located at WFP Menzies#1 Scale Site 1004 RWC DCR MATCHLEE LTD PARTNERSHIP Tsowwin River estuary Tahsis Inlet 2502872120 1005 RSK DND TOMPKINS POST AND RAIL Across the street from old corwood 1006 RWC DNI CANADIAN OVERSEAS FOG CREEK - North side of King Isla 6046820425 1007 RKB DSE DYNAMIC WOOD PRODUCTS 1839 Brilliant Road Castlegar BC 2503653669 1008 RWC DCR ROBERT (ANDY) ANDERSEN Mobile Scale Site for use in marine 1009 ROM DPG DUNKLEY- LEASE OF SITE 411 BEAR LAKE Winton Bear lake site- Current Leas 2509984421 101 RWC DNI WESTERN FOREST PRODUCTS INC. MAHATTA RIVER (Quatsino Sound) - Lo 2502863767 1010 RWC DCR WESTERN FOREST PRODUCTS INC. STAFFORD Stafford Lake , end of Loughborough 2502863767 1011 RWC DSI LADYSMITH WFP VIRTUAL WEIGH SCALE Latitude 48 59' 57.79"N 2507204200 1012 RWC DNI BELLA COOLA RESOURCE SOCIETY (Bella Coola Community Forest) VIRT 2509822515 1013 RWC DSI L AND Y CUTTING EDGE MILL The old Duncan Valley Timber site o 2507151678 1014 RWC DNI INTERNATIONAL FOREST PRODUCTS LTD Sandal Bay - Water Scale. 2 out of 2502861881 1015 RWC DCR BRUCE EDWARD REYNOLDS Mobile Scale Site for use in marine 1016 RWC DSI MUD BAY COASTLAND VIRTUAL W/S Ladysmith virtual site 2507541962 1017 RWC DSI MUD BAY COASTLAND VIRTUAL W/S Coastland Virtual Weigh Scale at Mu 2507541962 1018 RTO DOS NORTH ENDERBY TIMBER Malakwa Scales 2508389668 1019 RWC DSI HAULBACK MILLYARD GALIANO 200 Haulback Road, DL 14 Galiano Is 102 RWC DNI PORT MCNEILL PORT MCNEILL 2502863767 1020 RWC DSI KURUCZ ROVING Roving, Port Alberni area 1021 RWC DNI INTERNATIONAL FOREST PRODUCTS LTD-DEAN 1 Dean Channel Heli Water Scale. -

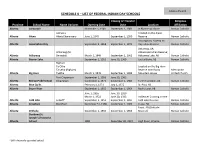

Schedule K – List of Federal Indian Day Schools

SCHEDULE K – LIST OF FEDERAL INDIAN DAY SCHOOLS Closing or Transfer Religious Province School Name Name Variants Opening Date Date Location Affiliation Alberta Alexander November 1, 1949 September 1, 1981 In Riviere qui Barre Roman Catholic Glenevis Located on the Alexis Alberta Alexis Alexis Elementary June 1, 1949 September 1, 1990 Reserve Roman Catholic Assumption, Alberta on Alberta Assumption Day September 9, 1968 September 1, 1971 Hay Lakes Reserve Roman Catholic Atikameg, AB; Atikameg (St. Atikamisie Indian Reserve; Alberta Atikameg Benedict) March 1, 1949 September 1, 1962 Atikameg Lake, AB Roman Catholic Alberta Beaver Lake September 1, 1952 June 30, 1960 Lac La Biche, AB Roman Catholic Bighorn Ta Otha Located on the Big Horn Ta Otha (Bighorn) Reserve near Rocky Mennonite Alberta Big Horn Taotha March 1, 1949 September 1, 1989 Mountain House United Church Fort Chipewyan September 1, 1956 June 30, 1963 Alberta Bishop Piché School Chipewyan September 1, 1971 September 1, 1985 Fort Chipewyan, AB Roman Catholic Alberta Blue Quills February 1, 1971 July 1, 1972 St. Paul, AB Alberta Boyer River September 1, 1955 September 1, 1964 Rocky Lane, AB Roman Catholic June 1, 1916 June 30, 1920 March 1, 1922 June 30, 1933 At Beaver Crossing on the Alberta Cold Lake LeGoff1 September 1, 1953 September 1, 1997 Cold Lake Reserve Roman Catholic Alberta Crowfoot Blackfoot December 31, 1968 September 1, 1989 Cluny, AB Roman Catholic Faust, AB (Driftpile Alberta Driftpile September 1, 1955 September 1, 1964 Reserve) Roman Catholic Dunbow (St. Joseph’s) Industrial Alberta School 1884 December 30, 1922 High River, Alberta Roman Catholic 1 Still a federally-operated school.