The 2014 Nobel Prize in Physiology Or Medicine: a Spatial Model for Cognitive Neuroscience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laureadas Com O Nobel Na Fisiologia Ou Medicina (1995-2015)

No trono da ciência II: laureadas com o Nobel na Fisiologia ou Medicina (1995-2015) On the Throne of Science II: Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine (1995-2015) LUZINETE SIMÕES MINELLA Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina | UFSC RESUMO O artigo dá continuidade a uma pesquisa mais ampla sobre as trajetórias das doze cientistas que receberam o Nobel na Fisiologia ou Medicina entre 1947 e 2015. Na fase anterior foram analisadas as trajetó- rias das cinco pioneiras, laureadas entre 1947 e 1988 e nesta segunda etapa, são abordadas suas sucessoras, as sete premiadas entre 1995 e 2015. A análise das suas autobiografias, discursos e palestras disponíveis no site do prêmio, além de outras fontes, se fundamenta numa perspectiva balizada pela crítica feminista à ciência bem como pelos avanços dos estudos do campo de gênero e ciências e da história da ciência. O artigo tenta identificar semelhanças e diferenças entre as pioneiras e as sucessoras na tentativa de contribuir para o debate sobre as especificidades da feminização das carreiras científicas. 85 Palavras-chave Gênero e Ciências – Nobel – Fisiologia ou Medicina. ABSTRACT The article gives continuity to a broader research on the trajectories of the twelve scientists who received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine between 1947 and 2015. In the previous phase, the trajectories of the five pioneers awarded between 1947 and 1988 were analyzed, and, in this second phase, their successors, the seven awarded between 1995 and 2015, were approached. The analysis of their autobiographies, speeches and lectures available on the award site, in addition to other sources, is based on a feminist critique of science as well as advances of the studies in the field of gender and science and the history of science. -

Of Boundary Extension: Anticipatory Scene Representation Across Development and Disorder

Received: 23 July 2016 | Revised: 14 January 2017 | Accepted: 19 January 2017 DOI: 10.1002/hipo.22728 RESEARCH ARTICLE Testing the “Boundaries” of boundary extension: Anticipatory scene representation across development and disorder G. Spano1,2 | H. Intraub3 | J. O. Edgin1,2,4 1Department of Psychology, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721 Abstract 2Cognitive Science Program, University of Recent studies have suggested that Boundary Extension (BE), a scene construction error, may be Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721 linked to the function of the hippocampus. In this study, we tested BE in two groups with varia- 3Department of Psychological and Brain tions in hippocampal development and disorder: a typically developing sample ranging from Sciences, University of Delaware, Newark, preschool to adolescence and individuals with Down syndrome. We assessed BE across three dif- Delaware 19716 ferent test modalities: drawing, visual recognition, and a 3D scene boundary reconstruction task. 4Sonoran University Center for Excellence in Despite confirmed fluctuations in memory function measured through a neuropsychological Developmental Disabilities, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721 assessment, the results showed consistent BE in all groups across test modalities, confirming the Correspondence near universal nature of BE. These results indicate that BE is an essential function driven by a com- Goffredina Spano, Wellcome Trust Centre plex set of processes, that occur even in the face of delayed memory development and for Neuroimaging, Institute of Neurology, hippocampal dysfunction in special populations. University College London, 12 Queen Square, London WC1N 3BG, UK. Email: [email protected] KEYWORDS Funding information down syndrome, memory development, hippocampus, prediction error, top-down influences LuMind Research Down Syndrome Foundation; Research Down Syndrome and the Jerome Lejeune Foundation; Molly Lawson Graduate Fellow in Down Syndrome Research (GS). -

Cognitive Map Formation Through Sequence Encoding by Theta Phase Precession

LETTER Communicated by A. David Redish Cognitive Map Formation Through Sequence Encoding by Theta Phase Precession Hiroaki Wagatsuma [email protected] Laboratory for Dynamics of Emergent Intelligence, RIKEN BSI, Wako-shi, Saitama 351-0198, Japan Yoko Yamaguchi [email protected] Laboratory for Dynamics of Emergent Intelligence, RIKEN BSI, Wako-shi, Saitama 351- 0198, Japan; College of Science and Engineering, Tokyo Denki University, Hatoyama, Saitama 350-0394, Japan; and CREST, Japan Science and Technology Corporation The rodent hippocampus has been thought to represent the spatial en- vironment as a cognitive map. The associative connections in the hip- pocampus imply that a neural entity represents the map as a geometrical network of hippocampal cells in terms of a chart. According to recent experimental observations, the cells fire successively relative to the theta oscillation of the local field potential, called theta phase precession, when the animal is running. This observation suggests the learning of temporal sequences with asymmetric connections in the hippocampus, but it also gives rather inconsistent implications on the formation of the chart that should consist of symmetric connections for space coding. In this study, we hypothesize that the chart is generated with theta phase coding through the integration of asymmetric connections. Our computer experiments use a hippocampal network model to demonstrate that a geometrical network is formed through running experiences in a few minutes. Asymmetric connections are found to remain and dis- tribute heterogeneously in the network. The obtained network exhibits the spatial localization of activities at each instance as the chart does and their propagation that represents behavioral motions with multidirec- tional properties. -

Position–Theta-Phase Model of Hippocampal Place Cell Activity Applied to Quantification of Running Speed Modulation of Firing Rate

Position–theta-phase model of hippocampal place cell activity applied to quantification of running speed modulation of firing rate Kathryn McClaina,b,1, David Tingleyb, David J. Heegera,c,1, and György Buzsákia,b,1 aCenter for Neural Science, New York University, New York, NY 10003; bNeuroscience Institute, New York University, New York, NY 10016; and cDepartment of Psychology, New York University, New York, NY 10003 Edited by Terrence J. Sejnowski, Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, CA, and approved November 18, 2019 (received for review July 24, 2019) Spiking activity of place cells in the hippocampus encodes the Another challenge in understanding this system is the dynamic animal’s position as it moves through an environment. Within a interaction between the rate code and phase code. As these codes cell’s place field, both the firing rate and the phase of spiking in combine, different formats of information are conveyed simulta- the local theta oscillation contain spatial information. We propose a neously in place cell spiking. The interaction can produce unin- – position theta-phase (PTP) model that captures the simultaneous tuitive, although entirely predictable, results in traditional analyses expression of the firing-rate code and theta-phase code in place cell of place cell activity. These practical challenges have hindered the spiking. This model parametrically characterizes place fields to com- pare across cells, time, and conditions; generates realistic place cell effort to explain variability in hippocampal firing rates. A com- simulation data; and conceptualizes a framework for principled hy- putational tool is needed that accounts for the well-established pothesis testing to identify additional features of place cell activity. -

2 Lez Concept of Synapses

Synapse • Gaps Between Neurons A synapse is a specialised junction between 2 neurones where the nerve impulse is passed from one neuron to another Santiago Ramón Camillo Golgi y Cajal The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1906 was awarded jointly to Camillo Golgi and Santiago Ramón y Cajal "in recognition of their work on the structure of the nervous system Reticular vs Neuronal Doctrine The 1930 s and 1940s was a time of controversy between proponents of chemical and electrical theories of synaptic transmission. Henry Dale was a pharmacologist and a principal advocate of chemical transmission. His most prominent adversary was the neurophysiologist, JohnEccles. Otto Loewi, MD Nobel Laureate (1936) Types of Synapses • Synapses are divided into 2 groups based on zones of apposition: • Electrical • Chemical – Fast Chemical – Modulating (slow) Chemical Gap-junction Channels • Connect communicating cells at an electrical synapse • Consist of a pair of cylinders (connexons) – one in presynaptic cell, one in post – each cylinder made of 6 protein subunits – cylinders meet in the gap between the two cell membranes • Gap junctions serve to synchronize the activity of a set of neurons Electrical synapse Electrical Synapses • Common in invertebrate neurons involved with important reflex circuits. • Common in adult mammalian neurons, and in many other body tissues such as heart muscle cells. • Current generated by the action potential in pre-synaptic neuron flows through the gap junction channel into the next neuron • Send simple depolarizing -

The Hippocampus Marion Wright* Et Al

WikiJournal of Medicine, 2017, 4(1):3 doi: 10.15347/wjm/2017.003 Encyclopedic Review Article The Hippocampus Marion Wright* et al. Abstract The hippocampus (named after its resemblance to the seahorse, from the Greek ἱππόκαμπος, "seahorse" from ἵππος hippos, "horse" and κάμπος kampos, "sea monster") is a major component of the brains of humans and other vertebrates. Humans and other mammals have two hippocampi, one in each side of the brain. It belongs to the limbic system and plays important roles in the consolidation of information from short-term memory to long-term memory and spatial memory that enables navigation. The hippocampus is located under the cerebral cortex; (allocortical)[1][2][3] and in primates it is located in the medial temporal lobe, underneath the cortical surface. It con- tains two main interlocking parts: the hippocampus proper (also called Ammon's horn)[4] and the dentate gyrus. In Alzheimer's disease (and other forms of dementia), the hippocampus is one of the first regions of the brain to suffer damage; short-term memory loss and disorientation are included among the early symptoms. Damage to the hippocampus can also result from oxygen starvation (hypoxia), encephalitis, or medial temporal lobe epilepsy. People with extensive, bilateral hippocampal damage may experience anterograde amnesia (the inability to form and retain new memories). In rodents as model organisms, the hippocampus has been studied extensively as part of a brain system responsi- ble for spatial memory and navigation. Many neurons in the rat and mouse hippocampus respond as place cells: that is, they fire bursts of action potentials when the animal passes through a specific part of its environment. -

Sir Charles Sherrington'sthe Integrative Action of the Nervous System: a Centenary Appreciation

doi:10.1093/brain/awm022 Brain (2007), 130, 887^894 OCCASIONAL PAPER Sir Charles Sherrington’sThe integrative action of the nervous system: a centenary appreciation Robert E. Burke Formerly Chief of the Laboratory of Neural Control, National Institute of Neurological Disorders, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA Present address: P.O. Box 1722, El Prado, NM 87529,USA E-mail: [email protected] In 1906 Sir Charles Sherrington published The Integrative Action of the Nervous System, which was a collection of ten lectures delivered two years before at Yale University in the United States. In this monograph Sherrington summarized two decades of painstaking experimental observations and his incisive interpretation of them. It settled the then-current debate between the ‘‘Reticular Theory’’ versus ‘‘Neuron Doctrine’’ ideas about the fundamental nature of the nervous system in mammals in favor of the latter, and it changed forever the way in which subsequent generations have viewed the organization of the central nervous system. Sherrington’s magnum opus contains basic concepts and even terminology that are now second nature to every student of the subject. This brief article reviews the historical context in which the book was written, summarizes its content, and considers its impact on Neurology and Neuroscience. Keywords: Neuron Doctrine; spinal reflexes; reflex coordination; control of movement; nervous system organization Introduction The first decade of the 20th century saw two momentous The Silliman lectures events for science. The year 1905 was Albert Einstein’s Sherrington’s 1906 monograph, published simultaneously in ‘miraculous year’ during which three of his most celebrated London, New Haven and New York, was based on a series papers in theoretical physics appeared. -

Mind-Wandering in People with Hippocampal Damage

This Accepted Manuscript has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. Research Articles: Behavioral/Cognitive Mind-wandering in people with hippocampal damage Cornelia McCormick1, Clive R. Rosenthal2, Thomas D. Miller2 and Eleanor A. Maguire1 1Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging, Institute of Neurology, University College London, London, WC1N 3AR, UK 2Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX3 9DU, UK DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1812-17.2018 Received: 29 June 2017 Revised: 21 January 2018 Accepted: 24 January 2018 Published: 12 February 2018 Author contributions: C.M., C.R.R., T.D.M., and E.A.M. designed research; C.M. performed research; C.M., C.R.R., T.D.M., and E.A.M. analyzed data; C.M., C.R.R., T.D.M., and E.A.M. wrote the paper. Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests. We thank all the participants, particularly the patients and their relatives, for the time and effort they contributed to this study. We also thank the consultant neurologists: Drs. M.J. Johnson, S.R. Irani, S. Jacobs and P. Maddison. We are grateful to Martina F. Callaghan for help with MRI sequence design, Trevor Chong for second scoring the Autobiographical Interview, Alice Liefgreen for second scoring the mind-wandering thoughts, and Elaine Williams for advice on hippocampal segmentation. E.A.M. and C.M. are supported by a Wellcome Principal Research Fellowship to E.A.M. (101759/Z/13/Z) and the Centre by a Centre Award from Wellcome (203147/Z/16/Z). -

Cajal, Golgi, Nansen, Schäfer and the Neuron Doctrine

Full text provided by www.sciencedirect.com Feature Endeavour Vol. 37 No. 4 Cajal, Golgi, Nansen, Scha¨ fer and the Neuron Doctrine 1, Ortwin Bock * 1 Park Road, Rosebank, 7700 Cape Town, South Africa The Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine of 1906 was interconnected with each other as well as connected with shared by the Italian Camillo Golgi and the Spaniard the radial bundle, whereby a coarsely meshed network of Santiago Ramo´ n y Cajal for their contributions to the medullated fibres is produced which can already be seen at 2 knowledge of the micro-anatomy of the central nervous 60 times magnification’. Gerlach’s work on vertebrates system. In his Nobel Lecture, Golgi defended the going- helped to consolidate the evolving Reticular Theory which out-of-favour Reticular Theory, which stated that the postulated that all the cells of the central nervous system nerve cells – or neurons – are fused together to form a were joined together like an electricity distribution net- diffuse network. Reticularists like Golgi insisted that the work. Gerlach was one of the most influential anatomists of axons physically join one nerve cell to another. In con- his day and the author of many books, not least the 1848 trast, Cajal in his lecture said that his own studies Handbuch der Allgemeinen und Speciellen Gewebelehre des confirmed the observations of others that the neurons Menschlichen Ko¨rpers: fu¨ r Aerzte und Studirende. For are independent of one another, a fact which is the twenty years he lent his considerable credibility to the anatomical basis of the now-accepted Neuron Doctrine Reticular Theory. -

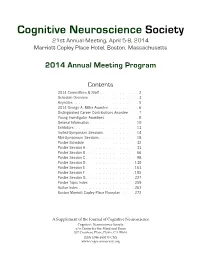

CNS 2014 Program

Cognitive Neuroscience Society 21st Annual Meeting, April 5-8, 2014 Marriott Copley Place Hotel, Boston, Massachusetts 2014 Annual Meeting Program Contents 2014 Committees & Staff . 2 Schedule Overview . 3 . Keynotes . 5 2014 George A . Miller Awardee . 6. Distinguished Career Contributions Awardee . 7 . Young Investigator Awardees . 8 . General Information . 10 Exhibitors . 13 . Invited-Symposium Sessions . 14 Mini-Symposium Sessions . 18 Poster Schedule . 32. Poster Session A . 33 Poster Session B . 66 Poster Session C . 98 Poster Session D . 130 Poster Session E . 163 Poster Session F . 195 . Poster Session G . 227 Poster Topic Index . 259. Author Index . 261 . Boston Marriott Copley Place Floorplan . 272. A Supplement of the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience Cognitive Neuroscience Society c/o Center for the Mind and Brain 267 Cousteau Place, Davis, CA 95616 ISSN 1096-8857 © CNS www.cogneurosociety.org 2014 Committees & Staff Governing Board Mini-Symposium Committee Roberto Cabeza, Ph.D., Duke University David Badre, Ph.D., Brown University (Chair) Marta Kutas, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Adam Aron, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Helen Neville, Ph.D., University of Oregon Lila Davachi, Ph.D., New York University Daniel Schacter, Ph.D., Harvard University Elizabeth Kensinger, Ph.D., Boston College Michael S. Gazzaniga, Ph.D., University of California, Gina Kuperberg, Ph.D., Harvard University Santa Barbara (ex officio) Thad Polk, Ph.D., University of Michigan George R. Mangun, Ph.D., University of California, -

Decoding Representations of Scenes in the Medial Temporal Lobes

HIPPOCAMPUS 22:1143–1153 (2012) Decoding Representations of Scenes in the Medial Temporal Lobes Heidi M. Bonnici,1 Dharshan Kumaran,2,3 Martin J. Chadwick,1 Nikolaus Weiskopf,1 Demis Hassabis,4 and Eleanor A. Maguire1* ABSTRACT: Recent theoretical perspectives have suggested that the (Eichenbaum, 2004; Johnson et al., 2007: Kumaran function of the human hippocampus, like its rodent counterpart, may be et al., 2009) and even visual perception (Lee et al., best characterized in terms of its information processing capacities. In this study, we use a combination of high-resolution functional magnetic 2005; Graham et al., 2006, 2010). Current perspec- resonance imaging, multivariate pattern analysis, and a simple decision tives, therefore, have emphasized that the function of making task, to test specific hypotheses concerning the role of the the hippocampus, and indeed surrounding areas within medial temporal lobe (MTL) in scene processing. We observed that the medial temporal lobe (MTL), may be best charac- while information that enabled two highly similar scenes to be distin- guished was widely distributed throughout the MTL, more distinct scene terized by understanding the nature of the information representations were present in the hippocampus, consistent with its processing they perform. role in performing pattern separation. As well as viewing the two similar The application of multivariate pattern analysis scenes, during scanning participants also viewed morphed scenes that (MVPA) techniques applied to functional magnetic spanned a continuum between the original two scenes. We found that patterns of hippocampal activity during morph trials, even when resonance imaging (fMRI) data (Haynes and Rees, perceptual inputs were held entirely constant (i.e., in 50% morph 2006; Norman et al., 2006) offers the possibility of trials), showed a robust relationship with participants’ choices in the characterizing the types of neural representations and decision task. -

Is Neuroscience a Bigger Threat Than Artifical Intelligence

Is Neuroscience a Bigger Threat than Artificial Intelligence? IBM’s Jeopardy winning computer Watson is a serious threat, not just to the livelihood of medical diagnosticians, but to other professionals who may find themselves going the way of welders. Besides its economic threat, the advance of AI seems to pose a cultural threat: if physical systems can do what we do without thought to give meaning to their achievements, the conscious human mind will be displaced from its unique role in the universe as a creative, responsible, rational agent. But this worry has a more powerful basis in the Nobel Prize winning discoveries of a quartet of neuroscientists—Eric Kandel, John O’Keefe, Edvard, and May-Britt Moser. For between them they have shown that the human brain doesn’t work the way conscious experience suggests at all. Instead it operates to deliver human achievements in the way IBM’s Watson does. Thoughts with meaning have no more role in the human brain than in artificial intelligence. Consciousness tells us that we employ a theory of mind, both to decide on our own actions and to predict and explain the behavior of others. According to this theory there have to be particular belief/desire pairings somewhere in our brains working together to bring about movements of the body, including speech and writing. Which beliefs and desires in particular? Roughly speaking it’s the contents of beliefs and desires—what they are about—that pair them up to drive our actions. The desires represent the ends, the beliefs record the available means to attain them.