The Diverging South

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Is Use of Cosmetics Anti-Socialist?”: Gendered Consumption and the Fashioning of Urban Womanhood in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania, 1975-1990

“IS USE OF COSMETICS ANTI-SOCIALIST?”: GENDERED CONSUMPTION AND THE FASHIONING OF URBAN WOMANHOOD IN DAR ES SALAAM, TANZANIA, 1975-1990 By TRACI L.YODER A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2006 Copyright 2006 by Traci L. Yoder ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to offer thanks and gratitude to Stacey Langwick, Sue O’Brien, and Florence Babb for their invaluable advice and unwavering encouragement throughout this project. I would also like to extend my appreciation to Faith Warner and the rest of the Department of Anthropology at Bloomsburg University. I am grateful to Peter Malanchuk for helping me to gain access to the archival newspapers that became the foundation of my study. I would also like to thank the Center for African Studies for providing me with Foreign Language and Area Studies Scholarships for the study of Swahili. Rose Lugano in particular has helped me with the Swahili translations in this paper. I would additionally like to thank Dr. Ruth Meena of the University of Dar es Salaam for her insights about the changing landscape of media in Tanzania over the last twenty years. I also thank all of my friends and classmates who have helped me to shape my ideas for this study. I want to offer my gratitude to my mother for her careful reading of this paper and to my father for his unwavering confidence. Finally, I thank Shelly for his patience, encouragement, and support throughout this project. -

The Term Break Was a Busy Time for Dr. Laura Fair Who Was Celebrating

The term break was a busy time for Dr. Laura Fair who was celebrating the publication of her new book, Historia ya Jamii ya Zanzibar na Nyimbo za Siti binti Saad (TWAWEZA 2013). The book was officially launched in Nairobi, Kenya on December 20, 2013. The event was organized by the publisher, Professor Kimani Njogu of TWAWEZA, and included a panel discussion with leading Kenyan academics from the University of Nairobi, Kenyatta University, and the Catholic University of East Africa. Dr. Fair was then invited to launch the book in Zanzibar as part of the opening ceremonies of a new NGO bearing the name of the singer, Siti binti Saad, whose life, career and political struggles are at the center of Fair’s book. This evening of celebration was attended by the President of Zanzibar: Dr. Ali Mohamed Shein, the former President of Tanzania: Ali Hassan Mwinyi (1985-1995), numerous other dignitaries and 300 select invited guests. The events were broadcast live on television in Zanzibar and the Tanzanian mainland. Pictures of the event can be found at http://michuzi- matukio.blogspot.nl/2014/01/dkt-shein-katika-uzinduzi-wa-taasisi-ya.html The Department of History at the University of Dar es Salaam also organized a seminar about the book on January 9, 2014, which was attended by faculty and students from the departments of History, Development Studies, Literature, Kiswahili and Fine and Performing Arts. Publication of the book was made possible by a MSU Humanities and Arts Research Program Production Grant supplemented with research funds provided by the Department of History. -

Inside This Issue

1 Photo: FAO/Emmanuel Kihaule Photo: ©FAO/Luis Tato Inside this issue Message from FAO Representative 2 Field visit to RICE project Iringa 5 2018 WFD celebrations highlights 3 Field visits to SAGCOT partners in Iringa, Mbeya 6 Panel Discussion 4 WFD celebrations 10 Media Coverage 12 Cover Photo: Minister of Agriculture, Dr. Eng. Charles Tizeba( 2nd right) looking at photos and publications at display soon after a panel discussion on the 2018 World Food Day that was held at the Sokoine University of Agriculture (SUA) in Morogoro. Others in the photo from left are WFP Head of Programme, Tiziana Zoccheddu, FAO Representative, Fred Kafeero and Executive Director of the Farmers Groups Network of Tanzania (MVIWATA) Stephen Ruvuga. Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN, House H Sida, Ali Hassan Mwinyi Rd, Ada Estate P.O Box 2, Dar es Salaam, Tel: +255 22 2664557-9 Fax: +255 22 2667286 Twitter: @FAOTanzania Website: http://www.fao.org/tanzania/en/ 2 Message from FAO Representative Celebrating WFD 2018 in Tanzania 2 Welcome! Dear esteemed partners and readers, poor live, and where they de- pend on agriculture, fisheries Warm Greetings from the Food and Agriculture or forestry as their main Organization of the United Nations (FAO) on this source of income and food. important occassion at which we celebrate the World Food Day 2018. This year’s theme reminds us that Our Everyone has a role to play in Actions are Our Future, and that if we take the right achieving Zero Hunger. actions, we can ensure a world free from hunger by 2030. -

The 2005 General Elections in Tanzania: Implications for Peace and Security in Southern Africa Julius Nyang’Oro

The 2005 General Elections in Tanzania: Implications for Peace and Security in Southern Africa Julius Nyang’oro ISS Paper 122 • February 2006 Price: R15.00 INTRODUCTION was underscored by its leading role in the establishment of the Southern African Development Coordinating Southern Africa is a region that has historically Conference (SADCC), in 1979, an organisation whose experienced civil and military conflict. In the two primary objectives were to reduce the economic decades preceding democratic change in South Africa, dependence of the region on South Africa; to forge the region easily earned the honour of being one of links to create conditions for regional integration; and the most violent on the African continent. Much of the to coordinate regional economic policies for purposes conflict in the region was directly or indirectly related of economic liberation.2 to the apartheid situation in South Africa.1 Examples of either the direct or indirect relationship between the Tanzania was one of the first countries to embrace apartheid regime and conflict in the region included: the wave of multiparty politics and democratisation the Mozambican civil war between the ruling party that swept the region in the early 1990s. For a long Frelimo and the rebel movement time, Botswana was the only country in Renamo, which ended with the signing the region that had a multiparty political of the Rome peace accords in 1992, system, although the dominance of the and the Angolan civil war between Tanzania was Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) had the MPLA government and the rebel effectively made Botswana a one party movement Unita led by Jonas Savimbi. -

Tanzania Human Development Report 2014 United Republic of Tanzania Economic Transformation for Human Development Tanzania Human Development Report 2014

Tanzania Human Development Report 2014 United Republic of Tanzania Economic Transformation for Human Development Tanzania Human Development Report 2014 Economic Transformation for Human Development United Republic of Tanzania Implementing Partner Tanzania Human Development Report 2014 Economic Transformation for Human Development Copyright © 2015 Published by Economic and Social Research Foundation 51 Uporoto Street (Off Ali Hassan Mwinyi Road), Ursino Estates P.O Box 31226, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania Tel: (+255) 22 2926084, 2926085, 2926086, 2926087, 2926088, 2926089, 2926090 Mobile: +255-754 780133, +255-655 780233 Fax: +255-22 2926083 Emails: [email protected] OR [email protected] Website: http://www.esrf.or.tz, http://www.thdr.or.tz United Nations Development Programme Tanzania Office 182 Mzinga way, Off Msasani Road Oysterbay P. O. Box 9182, Dar-Es-Salaam, Tanzania Tel (+255) 22 2112576 +255 686 036 436 UNDP Resident Representative & UN Resident Coordinator Office: Tel: +255 686 036 436 +255 686 036 436 UNDP Country Director Office: Tel: +255 0686 036 475 +255 0686 036 475 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.tz.undp.org Government of the United Republic of Tanzania Ministry of Finance, P. O. Box 9111, Dar es salaam. Phone: +255 22 2111174-6. Fax: +255 22 2110326 Website: http://www.mof.go.tz All rights reserved, no parts of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission ISBN: 978-9987-770-00-7 Artistic design of the cover by Mr. Haji Chilonga La petitie Galerie Oysterbay Shopping Centre Toure Drive-Masaki P.O. -

Tanzania: Lessons in Building Linkages for Competitive and Responsible Entrepreneurship

UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION TANZANIA: LESSONS IN BUILDING LINKAGES FOR COMPETITIVE AND RESPONSIBLE ENTREPRENEURSHIP TAMARA BEKEFI ISBN 92-1-106434-1 © 2006 The United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), the Fellows of Harvard College and Tamara Bekefi. This report may be cited as follows: Bekefi, Tamara. 2006. Tanzania: Lessons in building linkages for competitive and responsible entrepreneurship. UNIDO and Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. Tanzania: Lessons in building linkages for competitive and responsible entrepreneurship is one of the products of a research partnership between the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) and the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. The report forms part of a series of publications illustrating new models of multi-sector partnership and collective corporate action that are fostering small enterprise, promoting economic growth and reducing poverty through supporting competitive and responsible entrepreneurship and pro-poor industrial development in developing countries. Other titles in the series currently include: • Building linkages for competitive and responsible entrepreneurship: Innovative partnerships to foster small enterprise, promote economic growth and reduce poverty in developing countries. • Viet Nam: Lessons in building linkages for competitive and responsible entrepreneurship Authored by Tamara Bekefi Designed by Alison Beanland Printed by Puritan Press on 30% postconsumer paper The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization or the Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Cwr on EAST AFRICA If She Can Look up to You Shell Never Look Down on Herself

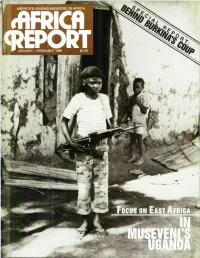

cwr ON EAST AFRICA If she can look up to you shell never look down on herself. <& 1965, The Coca-Cola Company JANUARY-FEBRUARY 1988 AMERICA'S VOLUME 33, NUMBER 1 LEADING MAGAZINE cBFRICfl ON AFRICA A Publication of the (REPORT African-American Institute Letters to the Editor Update The Editor: Andre Astrow African-American Institute Chairman Uganda Randolph Nugent Ending the Rule of the Gun 14 President By Catharine Watson Donald B. Easum Interview with President Yoweri Museveni IK By Margaret A. Novicki and Marline Dennis Kenya Publisher The Dynamics of Discontent 22 Frank E. Ferrari By Lindsey Hilsum Editor-in-Chief Dealing with Dissent Margaret A. Novicki Tanzania Interview with President Ali Hassan Mwinyi Managing Editor 27 Alana Lee By Margaret A. Novicki Acting Managing Editor Politics After Dodoma 30 Daphne Topouzis By Philip Smith Assistant Editor Burkina Special Report Andre Astrow A Revolution Derailed 33 Editorial Assistant By Ernest Harsch W. LaBier Jones Ethiopia On Famine's Brink 40 Art Director By Patrick Moser Joseph Pomar Advertising Director Eritrea: The Food Weapon 44 Barbara Spence Manonelie, Inc. By Michael Yellin (718) 773-9869. 756-9244 Sudan Contributing Editor Prospects for Peace? 45 Michael Maren By Robert M. Press Interns Somalia Joy Assefa Judith Surkis What Price Political Prisoners? 48 By Richard Greenfield Comoros Africa Reporl (ISSN 0001-9836), a non- 52 partisan magazine of African affairs, is The Politics of Isolation published bimonthly and is scheduled By Michael Griffin to appear at the beginning of each date period ai 833 United Nations Plaza. Education New York, N.Y. -

THE RISE and FALL of the GOVERNMENT of NATIONAL UNITY in ZANZIBAR a Critical Analysis of the 2015 Elections

162 DOI: 10.20940/JAE/2018/v17i1aDOI: 10.20940/JAE/2018/v17i1a8 JOURNAL8 OF AFRICAN ELECTIONS THE RISE AND FALL OF THE GOVERNMENT OF NATIONAL UNITY IN ZANZIBAR A Critical Analysis of the 2015 elections Nicodemus Minde, Sterling Roop and Kjetil Tronvoll Nicodemus Minde is a PhD candidate in the United States International University – Africa, Nairobi, Kenya Sterling Roop is a political analyst in Telluride, Co., USA Kjetil Tronvoll is Director, Oslo Analytica and Professor and Research Director, Peace and Conflict studies at Bjorknes University College, Oslo, Norway ABSTRACT This article analyses the pitfalls that characterised the emergence and eventual demise of the Government of National Unity (GNU) in Tanzania’s semi-autonomous region of Zanzibar. Drawn from continuous political and electoral observations in Zanzibar, the article analyses how the 2015 general elections contributed to the eventual dissolution of the GNU. The GNU in Zanzibar was a negotiated political settlement between two parties – the incumbent Chama cha Mapinduzi (CCM) and the Civic United Front (CUF). In particular, this article looks at how the start of the constitutional review process in Tanzania contributed to the withering of the GNU. Despite its undeniably noble agenda, the constitutional review process resuscitated old enmities between CCM and the CUF. The two parties’ divergent stances on the structure of the Union revived the rifts that characterised their relationship before the GNU. We analyse the election cycle rhetoric following the run-up to the elections and how this widened the GNU fissures leading to its eventual demise after the re-election in March 2016. After the 2015 elections were nullified, the CUF, which had claimed victory, boycotted the re-election. -

Tanzania Ages (13-15)

Tanzania Ages (13-15) The flag of Tanzania was adopted on June 30, 1964. It is the merger of the flags of Tanganyika and Zanzibar. The name Tanzania is derived from the names of the two states Tanganyika and Zanzibar that became united in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanganyika and Zanzibar. This was later renamed the United Republic of Tanzania. The flag is divided diagonally by a yellow-edged black band from the lower hoist-side corner. The green represents the natural vegetation present in the country, yellow represents the rich mineral deposits of the country, black represents the people of Tanzania, and blue represents the numerous lakes and rivers and the Indian Ocean. + = Flag of Tanganyika Flag of Zanzibar Flag of Tanzania COAT OF ARMS The golden top of the warriors shield in the coat of arms represents the minerals that can be found in the Republic. The torch in this part represents UHURU, a Swahili word meaning freedom. The red part underneath the flag symbolizes the rich and fertile soil of Africa. The wavy blue bands underneath the red represent the land, sea, lakes and the coastal lines of the United Republic. The spear in the shield signifies defense of freedom and the axe and hoe represent the development of the country. The motto of the United Republic, Uhuru na Umoja is written at the base of the coat of arms which signifies Mount Kilimanjaro. It means freedom and unity. GEOGRAPHY The United Republic of Tanzania is a country in East Africa. It is bordered by Kenya and Uganda to the north; Rwanda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the west; and Zambia, Malawi, and Mozambique to the south. -

Prospects of Democracy and Economic Development In

ifty years after independence, Tanzania has yet to realize the rallying cries of its liberation movement “Uhuru Na Kazi” (freedom and jobs), or to defeat “F the three scourges of poverty, ignorance, and disease. Though well intentioned, the efforts of Tanzania’s first president Julius Nyerere to reduce poverty and enhance social welfare failed to sustain economic growth, plunging the country into prolonged crisis. In the 1980s, Tanzania started liberalizing its economy, and with the collapse of communism in the 1990s, the country instituted a multi-party system. Over the past two decades, Tanzania has seen increased economic growth and political openings, but high levels of poverty, corruption, and limited state capacity still pose critical challenges to inclusive development and democratic consolidation. The writing of a new constitution now presents Tanzania with a fresh opportunity to build a foundation for achieving its independence goals of poverty eradication and political freedom. Tanzanians can make progress by: (1) forging alliances with domestic democratic forces; (2) exploiting the intense power struggle within the ruling party; and (3) taking advantage of the incumbent president’s interest in a democratic legacy. Through political will and popular participation, the country can effectively address its challenges and emerge as a true African success story. ” —Ibrahim Lipumba, December 9, 2011 FROM UJAMAA TO DEMOKRASIA: REFLECTING on 50 YEARS of INDEPENDENCE in TANZANIA and the WAY FORWARD Dr. Ibrahim Lipumba Reagan-Fascell Democracy Fellow National Endowment for Democracy Friday, December 9, 2011 The views expressed in this presentation represent the opinions and analysis of the speaker and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for Democracy or its staff. -

Managing the Government of Tanzania: Is the Fourth Regime on the Right Track in Fighting Ignorance, Poverty and Diseases? Norman A.S

Saudi Journal of Business and Management Studies ISSN 2415-6663 (Print) Scholars Middle East Publishers ISSN 2415-6671 (Online) Dubai, United Arab Emirates Website: http://scholarsmepub.com/ Managing the Government of Tanzania: Is the Fourth Regime on the Right Track in Fighting Ignorance, Poverty and Diseases? Norman A.S. King, Farles Ilomo University of Iringa, Tanzania Abstract: This paper deliberates the scenario of managing governments in general *Corresponding author and narrows to Tanzania government, specifically the administration of the fourth Norman A.S. King regime of president of the United Republic of Tanzania, His excellence, Jakaya Mrisho Kikwete. The paper traces the execution of the four regimes of presidency Article History from 1961 to 2015 and makes some examinations on the events and decisions made Received: 03.10.2017 during these regimes through an eye of a specialist. The study is a review in nature Accepted: 11.10.2017 and assimilates qualitative techniques in discussing and analyzing information. Published: 30.10.2017 Documentation, observation and experiential are the major information collection strategies employed in the study. The paper concludes by setting four propositions: DOI: First, that although it is evident that most fabulous practices are manifested during 10.21276/sjbms.2017.2.10.7 the Kikwete regime yet most of them did not originate from his regime. Secondly, that the revealed evil practices give a signal that the regime of Kikwete was transparent. Third, that the decisions that were made by his regime of accepting resignation of eminent ministers, signals prudence and reliability of the government. Fourth, that the decisions that were taken to revisit the mining contracts out of the main documents suggest courage, brilliance and objectivity of the President in dealing with national matters. -

Determinants and Mechanisms of National Identity Shift in Tanzania

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Plan B and other Reports Graduate Studies 5-2018 Determinants and Mechanisms of National Identity Shift in Tanzania Alexander C. Wendt Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Wendt, Alexander C., "Determinants and Mechanisms of National Identity Shift in Tanzania" (2018). All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. 1231. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports/1231 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Plan B and other Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DETERMINANTS AND MECHANISMS OF NATIONAL IDENTITY SHIFT IN TANZANIA by Alexander C. Wendt A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Political Science Approved: ____________________ ____________________ Anna Pechenkina, Ph. D. Colin Flint, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member ____________________ Christopher Conte, Ph.D. Committee Member UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2018 ii Copyright © Alexander C. Wendt 2018 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Determinants and Mechanisms of Identity Shift in Tanzania by Alexander C. Wendt, Master of Science Utah State University, 2018 Major Professor: Dr. Anna Pechenkina Department: Political Science Since gaining independence in 1961, Tanzania has enjoyed high levels of national identification, far higher than other states in east Africa. Yet, between 2005 and 2015, the Afrobarometer survey recorded a decline in the national identity and an increase in ethnic identities in Tanzania.