Summary Tanzania Human Development Report 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4 MEI, 2013 MREMA 1.Pmd

4 MEI, 2013 BUNGE LA TANZANIA _____________ MAJADILIANO YA BUNGE _______________ MKUTANO WA KUMI NA MOJA Kikao cha Kumi na Nane - Tarehe 4 Mei, 2013 (Mkutano Ulianza Saa Tatu Asubuhi) D U A Naibu Spika (Mhe. Job Y. Ndugai) Alisoma Dua NAIBU SPIKA: Waheshimiwa Wabunge tukae. Waheshimiwa Wabunge Mkutano wa 11 unaendelea, kikao hiki ni cha 18. HATI ZILIZOWASILISHWA MEZANI Hati Zifuatazo Ziliwasilishwa Mezani na:- WAZIRI WA MAMBO YA NDANI YA NCHI:- Randama za Makadirio ya Wizara ya Mambo ya Ndani ya Nchi kwa Mwaka wa Fedha 2013/2014. WAZIRI WA ULINZI NA JESHI LA KUJENGA TAIFA: Hotuba ya Bajeti ya Wizara ya Ulinzi na Jeshi la Kujenga Taifa kwa Mwaka wa Fedha 2013/2014. 1 4 MEI, 2013 MHE. OMAR R. NUNDU (K.n.y. MWENYEKITI WA KAMATI YA ULINZI NA USALAMA): Taarifa ya Mwenyekiti wa Kamati ya Ulinzi na Usalama Kuhusu Utekelezaji wa Majukumu ya Wizara ya Ulinzi na Jeshi la Kujenga Taifa kwa Mwaka wa Fedha 2012/2013 na Maoni ya Kamati Kuhusu Makadirio ya Mapato na Matumizi ya Wizara hiyo kwa Mwaka wa Fedha 2013/2014. MHE. CHRISTOWAJA G. MTINDA (K.n.y. MHE. MCH. ISRAEL Y. NATSE - MSEMAJI MKUU WA KAMBI YA UPINZANI WA WIZARA YA ULINZI NA JESHI LA KUJENGA TAIFA:- Taarifa ya Msemaji Mkuu wa Kambi ya Upinzani wa Wizara ya Ulinzi na Jeshi la Kujenga Taifa Kuhusu Makadirio ya Mapato na Matumizi ya Wizara hiyo kwa Mwaka wa Fedha 2013/2014. HOJA ZA SERIKALI Makadirio ya Matumizi ya Serikali kwa Mwaka 2013/2014 Wizara ya Ulinzi na Jeshi la Kujenga Taifa WAZIRI WA ULINZI NA JESHI LA KUJENGA TAIFA: Mheshimiwa Naibu Spika, kufuatia taarifa iliyowasilishwa leo hapa Bungeni na Mwenyekiti wa Kamati ya Kudumu ya Bunge ya Ulinzi na Usalama, naomba kutoa hoja kwamba Bunge lako Tukufu likubali kujadili na kupitisha Mpango na Makadirio ya Mapato na Matumizi ya Wizara ya Ulinzi na Jeshi la Kujenga Taifa kwa mwaka wa fedha 2013/2014. -

“Is Use of Cosmetics Anti-Socialist?”: Gendered Consumption and the Fashioning of Urban Womanhood in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania, 1975-1990

“IS USE OF COSMETICS ANTI-SOCIALIST?”: GENDERED CONSUMPTION AND THE FASHIONING OF URBAN WOMANHOOD IN DAR ES SALAAM, TANZANIA, 1975-1990 By TRACI L.YODER A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2006 Copyright 2006 by Traci L. Yoder ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to offer thanks and gratitude to Stacey Langwick, Sue O’Brien, and Florence Babb for their invaluable advice and unwavering encouragement throughout this project. I would also like to extend my appreciation to Faith Warner and the rest of the Department of Anthropology at Bloomsburg University. I am grateful to Peter Malanchuk for helping me to gain access to the archival newspapers that became the foundation of my study. I would also like to thank the Center for African Studies for providing me with Foreign Language and Area Studies Scholarships for the study of Swahili. Rose Lugano in particular has helped me with the Swahili translations in this paper. I would additionally like to thank Dr. Ruth Meena of the University of Dar es Salaam for her insights about the changing landscape of media in Tanzania over the last twenty years. I also thank all of my friends and classmates who have helped me to shape my ideas for this study. I want to offer my gratitude to my mother for her careful reading of this paper and to my father for his unwavering confidence. Finally, I thank Shelly for his patience, encouragement, and support throughout this project. -

Tarehe 4 Aprili, 2019

NAKALA MTANDAO(ONLINE DOCUMENT) BUNGE LA TANZANIA ________ MAJADILIANO YA BUNGE _________ MKUTANO WA KUMI NA TANO Kikao cha Tatu – Tarehe 4 Aprili, 2019 (Bunge Lilianza Saa Tatu Asubuhi) D U A Spika (Mhe. Job Y. Ndugai) Alisoma Dua SPIKA: Waheshimiwa Wabunge, naomba tukae. Leo ni kikao cha tatu cha Mkutano wetu wa Kumi na Tano. Katibu! NDG. STEPHEN KAGAIGAI – KATIBU WA BUNGE: HATI ZILIZOWASILISHWA MEZANI: Hati Zifuatazo Ziliwasilishwa Mezani na:- WAZIRI WA NCHI, OFISI YA WAZIRI MKUU, SERA, BUNGE, AJIRA, KAZI VIJANA NA WAZEE NA WENYE ULEMAVU: Taarifa ya Bajeti ya Ofisi ya Waziri Mkuu kwa mwaka wa fedha 2019/2020. MHE. MOHAMED O. MCHENGERWA - MWENYEKITI WA KAMATI YA KUDUMU YA BUNGE YA KATIBA NA SHERIA: Taarifa 1 NAKALA MTANDAO(ONLINE DOCUMENT) ya Kamati ya Kudumu ya Bunge ya Katiba na Sheria kuhusu utekelezaji wa majukumu ya Ofisi ya Waziri Mkuu kwa mwaka wa fedha 2018/2019 pamoja na Maoni ya Kamati kuhusu Makadirio ya Mapato na Matumizi ya Ofisi hiyo kwa mwaka wa fedha 2019/2020. MHE. HASNA S.K. MWILIMA (K.n.y. MWENYEKITI WA KAMATI YA KUDUMU YA BUNGE YA BAJETI): Taarifa ya Kamati ya Kudumu ya Bunge ya Bajeti kuhusu utekelezaji wa Bajeti ya Mfuko wa Bunge kwa Mwaka wa Fedha 2018/2019 pamoja na Maoni ya Kamati kuhusu Makadirio ya Mapato na Matumizi ya Mfuko huo kwa Mwaka wa Fedha 2019/2020. MHE. DKT. JASMINE T. BUNGA - MAKAMU MWENYEKITI WA KAMATI YA KUDUMU YA BUNGE YA MASUALA YA UKIMWI: Taarifa ya Kamati ya Kudumu ya Bunge ya Masuala ya UKIMWI kuhusu utekelezaji wa Bajeti ya Ofisi ya Waziri Mkuu (Tume ya Uratibu na Udhibiti wa UKIMWI) kwa mwaka wa fedha 2018/2019 pamoja na Maoni ya Kamati kuhusu Makadirio ya Mapato na Matumizi ya Ofisi hiyo kwa mwaka wa fedha 2019/2020. -

Speech by the President of the United Republic Of

SPEECH BY THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA, HIS EXCELLENCY BENJAMIN WILLIAM MKAPA, AT THE CELEBRATIONS MARKING THE 40TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE INDEPENDENCE OF TANZANIA MAINLAND, NATIONAL STADIUM, DAR ES SALAAM, 9 DECEMBER 2001 Your Excellency Daniel Toroitich arap Moi, President of the Republic of Kenya; Your Excellency Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, President of the Republic of Uganda; Honourable Dr. Ali Mohamed Shein, Vice-President of the United Republic of Tanzania; Honourable Amani Abeid Karume, President of the Revolutionary Government of Zanzibar; Honourable Frederick T. Sumaye, MP, Prime Minister; Honourable Justice Barnabas Samatta, Chief Justice of Tanzania; Honourable Shamsi Vuai Nahodha, Chief Minister of the Revolutionary Government of Zanzibar; Honourable Mama Maria Nyerere; Honourable Mama Fatma Karume; Honourable Chairmen, Vice-Chairmen and Leaders of Political Parties; Honourable Pandu Ameir Kificho, Speaker of the Zanzibar House of Representatives; Honourable Hamid Mahmoud, Chief Justice of Zanzibar; Honourable Retired Prime Ministers; Honourable Ministers and Members of Parliament; Excellencies High Commissioners and Ambassadors; Honourable Elders from the Independence Struggle; Distinguished Guests; Ladies and Gentlemen. My Fellow Citizens, We are today marking 40 years of our independence, the independence of Tanzania Mainland, then known as Tanganyika. We have just seen some of the Tanzanians who were born at the time of our independence. They are adults now. But they have no first hand experience of what it was like to live under colonialism. They only read about it, or are informed by those who lived through that experience. On a day like this, therefore, we need to remind ourselves of what our independence really means. -

The Term Break Was a Busy Time for Dr. Laura Fair Who Was Celebrating

The term break was a busy time for Dr. Laura Fair who was celebrating the publication of her new book, Historia ya Jamii ya Zanzibar na Nyimbo za Siti binti Saad (TWAWEZA 2013). The book was officially launched in Nairobi, Kenya on December 20, 2013. The event was organized by the publisher, Professor Kimani Njogu of TWAWEZA, and included a panel discussion with leading Kenyan academics from the University of Nairobi, Kenyatta University, and the Catholic University of East Africa. Dr. Fair was then invited to launch the book in Zanzibar as part of the opening ceremonies of a new NGO bearing the name of the singer, Siti binti Saad, whose life, career and political struggles are at the center of Fair’s book. This evening of celebration was attended by the President of Zanzibar: Dr. Ali Mohamed Shein, the former President of Tanzania: Ali Hassan Mwinyi (1985-1995), numerous other dignitaries and 300 select invited guests. The events were broadcast live on television in Zanzibar and the Tanzanian mainland. Pictures of the event can be found at http://michuzi- matukio.blogspot.nl/2014/01/dkt-shein-katika-uzinduzi-wa-taasisi-ya.html The Department of History at the University of Dar es Salaam also organized a seminar about the book on January 9, 2014, which was attended by faculty and students from the departments of History, Development Studies, Literature, Kiswahili and Fine and Performing Arts. Publication of the book was made possible by a MSU Humanities and Arts Research Program Production Grant supplemented with research funds provided by the Department of History. -

Volume 28 2001 Issue 88

Africa^ |*REVIEWOF n ^ Political Economy EDITORS The Review of African Political Economy (ROAPE) is published quarterly by Carfax Chris Allen, Jan Burgess and Morris Szeftel Publishing Company for the ROAPE international collective. Now 28 years old, ROAPE is a fully BOOK REVIEWS refereed journal covering all aspects of African political economy. ROAPE has always involved Ray Bush, Roy Love and Giles Mohan the readership in shaping the journal's coverage, welcoming contributions from grassroots organi- sations, women's organisations, trade unions and EDITORIAL WORKING GROUP political groups. The journal is unique in the Chris Allen, Carolyn Baylies, Sarah Bracking, comprehensiveness of its bibliographic referenc- Lynne Brydon, Janet Bujra, Jan Burgess, Ray Bush, ing, information monitoring, statistical documen- Carolyne Dennis, Graham Harrison, Jon Knox, tation and coverage of work-in-progress. Roy Love, Giles Mohan, Colin Murray, Mike Powell, Marcus Power, David Simon, Colin Editorial correspondence, including manuscripts Stoneman, Morris Szeftel, Tina Wallace, A. B. for submission, should be sent to Jan Burgess, Zack-Williams. ROAPE Publications Ltd., P.O. Box 678, Sheffield SI 1BF, UK. Tel: 44 +(0)114 267-6880; Fax 44 + (0)114 267-6881; e-mail: [email protected]. CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Africa: Rok Ajulu (Grahamstown), Yusuf Advertising: USA/Canada: The Advertising Bangura (Zaria), Billy Cobbett (Johannesburg), Manager, PCG, 875 Massachusetts Avenue, Suite Antonieta Coelho (Luanda), Bill Freund 81, Cambridge MA 02139, USA. EU/Rest of the (Durban), Jibril Ibrahim (Zaria), Amadina World: The Advertising Manager, Taylor & Lihamba (Dar es Salaam), Trevor Parfitt (Cairo), Francis, P.O. Box 25, Abingdon, Oxon., OX14 3UE, Lloyd Sachikonye (Harare). UK. Tel: +44 (0)1235 401 000; Fax: +44 (0)1235 401 550. -

Inside This Issue

1 Photo: FAO/Emmanuel Kihaule Photo: ©FAO/Luis Tato Inside this issue Message from FAO Representative 2 Field visit to RICE project Iringa 5 2018 WFD celebrations highlights 3 Field visits to SAGCOT partners in Iringa, Mbeya 6 Panel Discussion 4 WFD celebrations 10 Media Coverage 12 Cover Photo: Minister of Agriculture, Dr. Eng. Charles Tizeba( 2nd right) looking at photos and publications at display soon after a panel discussion on the 2018 World Food Day that was held at the Sokoine University of Agriculture (SUA) in Morogoro. Others in the photo from left are WFP Head of Programme, Tiziana Zoccheddu, FAO Representative, Fred Kafeero and Executive Director of the Farmers Groups Network of Tanzania (MVIWATA) Stephen Ruvuga. Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN, House H Sida, Ali Hassan Mwinyi Rd, Ada Estate P.O Box 2, Dar es Salaam, Tel: +255 22 2664557-9 Fax: +255 22 2667286 Twitter: @FAOTanzania Website: http://www.fao.org/tanzania/en/ 2 Message from FAO Representative Celebrating WFD 2018 in Tanzania 2 Welcome! Dear esteemed partners and readers, poor live, and where they de- pend on agriculture, fisheries Warm Greetings from the Food and Agriculture or forestry as their main Organization of the United Nations (FAO) on this source of income and food. important occassion at which we celebrate the World Food Day 2018. This year’s theme reminds us that Our Everyone has a role to play in Actions are Our Future, and that if we take the right achieving Zero Hunger. actions, we can ensure a world free from hunger by 2030. -

The 2005 General Elections in Tanzania: Implications for Peace and Security in Southern Africa Julius Nyang’Oro

The 2005 General Elections in Tanzania: Implications for Peace and Security in Southern Africa Julius Nyang’oro ISS Paper 122 • February 2006 Price: R15.00 INTRODUCTION was underscored by its leading role in the establishment of the Southern African Development Coordinating Southern Africa is a region that has historically Conference (SADCC), in 1979, an organisation whose experienced civil and military conflict. In the two primary objectives were to reduce the economic decades preceding democratic change in South Africa, dependence of the region on South Africa; to forge the region easily earned the honour of being one of links to create conditions for regional integration; and the most violent on the African continent. Much of the to coordinate regional economic policies for purposes conflict in the region was directly or indirectly related of economic liberation.2 to the apartheid situation in South Africa.1 Examples of either the direct or indirect relationship between the Tanzania was one of the first countries to embrace apartheid regime and conflict in the region included: the wave of multiparty politics and democratisation the Mozambican civil war between the ruling party that swept the region in the early 1990s. For a long Frelimo and the rebel movement time, Botswana was the only country in Renamo, which ended with the signing the region that had a multiparty political of the Rome peace accords in 1992, system, although the dominance of the and the Angolan civil war between Tanzania was Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) had the MPLA government and the rebel effectively made Botswana a one party movement Unita led by Jonas Savimbi. -

Tanzania Human Development Report 2014 United Republic of Tanzania Economic Transformation for Human Development Tanzania Human Development Report 2014

Tanzania Human Development Report 2014 United Republic of Tanzania Economic Transformation for Human Development Tanzania Human Development Report 2014 Economic Transformation for Human Development United Republic of Tanzania Implementing Partner Tanzania Human Development Report 2014 Economic Transformation for Human Development Copyright © 2015 Published by Economic and Social Research Foundation 51 Uporoto Street (Off Ali Hassan Mwinyi Road), Ursino Estates P.O Box 31226, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania Tel: (+255) 22 2926084, 2926085, 2926086, 2926087, 2926088, 2926089, 2926090 Mobile: +255-754 780133, +255-655 780233 Fax: +255-22 2926083 Emails: [email protected] OR [email protected] Website: http://www.esrf.or.tz, http://www.thdr.or.tz United Nations Development Programme Tanzania Office 182 Mzinga way, Off Msasani Road Oysterbay P. O. Box 9182, Dar-Es-Salaam, Tanzania Tel (+255) 22 2112576 +255 686 036 436 UNDP Resident Representative & UN Resident Coordinator Office: Tel: +255 686 036 436 +255 686 036 436 UNDP Country Director Office: Tel: +255 0686 036 475 +255 0686 036 475 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.tz.undp.org Government of the United Republic of Tanzania Ministry of Finance, P. O. Box 9111, Dar es salaam. Phone: +255 22 2111174-6. Fax: +255 22 2110326 Website: http://www.mof.go.tz All rights reserved, no parts of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission ISBN: 978-9987-770-00-7 Artistic design of the cover by Mr. Haji Chilonga La petitie Galerie Oysterbay Shopping Centre Toure Drive-Masaki P.O. -

Tanzania: Lessons in Building Linkages for Competitive and Responsible Entrepreneurship

UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION TANZANIA: LESSONS IN BUILDING LINKAGES FOR COMPETITIVE AND RESPONSIBLE ENTREPRENEURSHIP TAMARA BEKEFI ISBN 92-1-106434-1 © 2006 The United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), the Fellows of Harvard College and Tamara Bekefi. This report may be cited as follows: Bekefi, Tamara. 2006. Tanzania: Lessons in building linkages for competitive and responsible entrepreneurship. UNIDO and Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. Tanzania: Lessons in building linkages for competitive and responsible entrepreneurship is one of the products of a research partnership between the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) and the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. The report forms part of a series of publications illustrating new models of multi-sector partnership and collective corporate action that are fostering small enterprise, promoting economic growth and reducing poverty through supporting competitive and responsible entrepreneurship and pro-poor industrial development in developing countries. Other titles in the series currently include: • Building linkages for competitive and responsible entrepreneurship: Innovative partnerships to foster small enterprise, promote economic growth and reduce poverty in developing countries. • Viet Nam: Lessons in building linkages for competitive and responsible entrepreneurship Authored by Tamara Bekefi Designed by Alison Beanland Printed by Puritan Press on 30% postconsumer paper The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization or the Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Cwr on EAST AFRICA If She Can Look up to You Shell Never Look Down on Herself

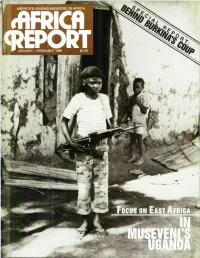

cwr ON EAST AFRICA If she can look up to you shell never look down on herself. <& 1965, The Coca-Cola Company JANUARY-FEBRUARY 1988 AMERICA'S VOLUME 33, NUMBER 1 LEADING MAGAZINE cBFRICfl ON AFRICA A Publication of the (REPORT African-American Institute Letters to the Editor Update The Editor: Andre Astrow African-American Institute Chairman Uganda Randolph Nugent Ending the Rule of the Gun 14 President By Catharine Watson Donald B. Easum Interview with President Yoweri Museveni IK By Margaret A. Novicki and Marline Dennis Kenya Publisher The Dynamics of Discontent 22 Frank E. Ferrari By Lindsey Hilsum Editor-in-Chief Dealing with Dissent Margaret A. Novicki Tanzania Interview with President Ali Hassan Mwinyi Managing Editor 27 Alana Lee By Margaret A. Novicki Acting Managing Editor Politics After Dodoma 30 Daphne Topouzis By Philip Smith Assistant Editor Burkina Special Report Andre Astrow A Revolution Derailed 33 Editorial Assistant By Ernest Harsch W. LaBier Jones Ethiopia On Famine's Brink 40 Art Director By Patrick Moser Joseph Pomar Advertising Director Eritrea: The Food Weapon 44 Barbara Spence Manonelie, Inc. By Michael Yellin (718) 773-9869. 756-9244 Sudan Contributing Editor Prospects for Peace? 45 Michael Maren By Robert M. Press Interns Somalia Joy Assefa Judith Surkis What Price Political Prisoners? 48 By Richard Greenfield Comoros Africa Reporl (ISSN 0001-9836), a non- 52 partisan magazine of African affairs, is The Politics of Isolation published bimonthly and is scheduled By Michael Griffin to appear at the beginning of each date period ai 833 United Nations Plaza. Education New York, N.Y. -

THE RISE and FALL of the GOVERNMENT of NATIONAL UNITY in ZANZIBAR a Critical Analysis of the 2015 Elections

162 DOI: 10.20940/JAE/2018/v17i1aDOI: 10.20940/JAE/2018/v17i1a8 JOURNAL8 OF AFRICAN ELECTIONS THE RISE AND FALL OF THE GOVERNMENT OF NATIONAL UNITY IN ZANZIBAR A Critical Analysis of the 2015 elections Nicodemus Minde, Sterling Roop and Kjetil Tronvoll Nicodemus Minde is a PhD candidate in the United States International University – Africa, Nairobi, Kenya Sterling Roop is a political analyst in Telluride, Co., USA Kjetil Tronvoll is Director, Oslo Analytica and Professor and Research Director, Peace and Conflict studies at Bjorknes University College, Oslo, Norway ABSTRACT This article analyses the pitfalls that characterised the emergence and eventual demise of the Government of National Unity (GNU) in Tanzania’s semi-autonomous region of Zanzibar. Drawn from continuous political and electoral observations in Zanzibar, the article analyses how the 2015 general elections contributed to the eventual dissolution of the GNU. The GNU in Zanzibar was a negotiated political settlement between two parties – the incumbent Chama cha Mapinduzi (CCM) and the Civic United Front (CUF). In particular, this article looks at how the start of the constitutional review process in Tanzania contributed to the withering of the GNU. Despite its undeniably noble agenda, the constitutional review process resuscitated old enmities between CCM and the CUF. The two parties’ divergent stances on the structure of the Union revived the rifts that characterised their relationship before the GNU. We analyse the election cycle rhetoric following the run-up to the elections and how this widened the GNU fissures leading to its eventual demise after the re-election in March 2016. After the 2015 elections were nullified, the CUF, which had claimed victory, boycotted the re-election.