Language Acquisition in a Deaf Child: the Interaction of Sign Variations, Speech, and Print Variations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ryokoakamaexploringemptines

University of Huddersfield Repository Akama, Ryoko Exploring Empitness: An Investigation of MA and MU in My Sonic Composition Practice Original Citation Akama, Ryoko (2015) Exploring Empitness: An Investigation of MA and MU in My Sonic Composition Practice. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/26619/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ EXPLORING EMPTINESS AN INVESTIGATION OF MA AND MU IN MY SONIC COMPOSITION PRACTICE Ryoko Akama A commentary accompanying the publication portfolio submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ! The University of Huddersfield School of Music, Humanities and Media April, 2015 Title: Exploring Emptiness Subtitle: An investigation of ma and mu in my sonic composition practice Name of student: Ryoko Akama Supervisor: Prof. -

Nemeth Code Uses Some Parts of Textbook Format but Has Some Idiosyncrasies of Its Own

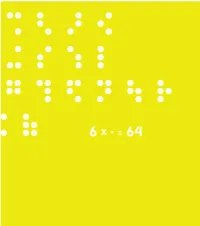

This book is a compilation of research, in “Understanding and Tracing the Problem faced by the Visually Impaired while doing Mathematics” as a Diploma project by Aarti Vashisht at the Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore. 6 DOTS 64 COMBINATIONS A Braille character is formed out of a combination of six dots. Including the blank space, sixty four combinations are possible using one or more of these six dots. CONTENTS Introduction 2 About Braille 32 Mathematics for the Visually Impaired 120 Learning Mathematics 168 C o n c l u s i o n 172 P e o p l e a n d P l a c e s 190 Acknowledgements INTRODUCTION This project tries to understand the nature of the problems that are faced by the visually impaired within the realm of mathematics. It is a summary of my understanding of the problems in this field that may be taken forward to guide those individuals who are concerned about this subject. My education in design has encouraged interest in this field. As a designer I have learnt to be aware of my community and its needs, to detect areas where design can reach out and assist, if not resolve, a problem. Thus began, my search, where I sought to grasp a fuller understanding of the situation by looking at the various mediums that would help better communication. During the project I realized that more often than not work happened in individual pockets which in turn would lead to regionalization of many ideas and opportunities. Data collection got repetitive, which would delay or sometimes even hinder the process. -

On the Compatibility of the Braille Code and Universal Grammar

On the Compatibility of the Braille Code and Universal Grammar Von der Philosophisch-Historischen Fakultät der Universität Stuttgart zur Erlangung der Würde eines Doktors der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) genehmigte Abhandlung Vorgelegt von Christine Lauenstein Hauptberichterin: Prof. Dr. Artemis Alexiadou Mitberichterin: Prof. Dr. Diane Wormsley Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 6.12.2006 Institute of English Linguistics Universität Stuttgart 2007 Data Perhaps. Perhaps not. Captain Picard This is hardly a scientific observation, Commander. Data Captain, the most elementary and valuable statement in science, the beginning of wisdom is I do not know. Star Trek: The Next Generation Where Silence has Lease Acknowledgements First I would like to thank the members of my thesis committee Artemis Alexiadou, that she has agreed on supervising this rather exotic topic, and Diane Wormsley for her support and undertaking the long journey to Germany. I would like to express my gratitude to all the people who have substantially contributed to my interest in braille and working with children who have a visual impairment, these are Dietmar Böhringer from Nikolauspflege Stuttgart, Maggie Granger, Diana King and above all Rosemary Parry, my braille teacher from The West of England School and College for young people with little or no sight, Exeter, UK. My special thanks goes to students and staff at The West of England School, the RNIB New College Worcester and the Royal National College for the Blind, Hereford for participating in the study. Further to those who helped to make this study possible: Paul Holland for enabling my numerous visits to The West of England School, Ruth Hardisty for co-ordinating the study, Chris Stonehouse and Mary Foulstone for their support in Worcester and Hereford and to Maggie Granger and Diana and Martin King for their friendship and for making things work even if braille was the most important thing in the world. -

Theknights Templars Owed Their Allegiance

GEUUhttp-v2.quark 4/4/03 5:18 PM Page 1 GEUUhttp-v2.quark 4/4/03 5:18 PM Page 3 Brad Steiger and Sherry Hansen Steiger 2 Gale Encyclopedia of the Unusual and Unexplained Brad E. Steiger and Sherry Hansen Steiger Project Editor Permissions Product Design Jolen Marya Gedridge Lori Hines Tracey Rowens Editorial Imaging and Multimedia Manufacturing Andrew Claps, Lynn U. Koch, Michael Reade Dean Dauphinais, Lezlie Light Rhonda A. Williams © 2003 by Gale. Gale is an imprint of The Gale age retrieval systems—without the written per- Since this page cannot legibly accommodate all Group, Inc., a division of Thomson Learning, Inc. mission of the publisher. copyright notices, the acknowledgements con- stitute an extension of the copyright notice. Gale and Design™ and Thomson Learning™ For permission to use material from this prod- are trademarks used herein under license. uct, submit your request via Web at While every effort has been made to ensure http://www.gale-edit.com/permissions, or you the reliability of the information presented in For more information, contact may download our Permissions Request form this publication, The Gale Group, Inc. does not The Gale Group, Inc. and submit your request by fax or mail to: guarantee the accuracy of the data contained 27500 Drake Road herein. The Gale Group, Inc. accepts no pay- Farmington Hills, MI 48331-3535 Permissions Department ment for listing; and inclusion in the publica- Or you can visit our Internet site at The Gale Group, Inc. tion of any organization, agency, institution, http://www.gale.com 27500 Drake Rd. -

30/06/2009 1 BRAILLE WITHOUT BORDERS; How Braille Can

Date submitted: 30/06/2009 BRAILLE WITHOUT BORDERS; How Braille can be used in creation of literature in indigenous languages Dipendra Manocha George Kerscher and Hiroshi Kawamura (DAISY Consortium, New Delhi – India, Missoula – USA, Tokyo – Japan) Meeting: 199. Libraries Serving Persons with Print Disabilities WORLD LIBRARY AND INFORMATION CONGRESS: 75TH IFLA GENERAL CONFERENCE AND COUNCIL 23-27 August 2009, Milan, Italy http://www.ifla.org/annual-conference/ifla75/index.htm Abstract There are innumerable languages spoken around the world which do not have any script. Many Indigenous communities use these languages only as spoken language. These Indigenous communities have a wealth of knowledge which they have gathered over generations. This knowledge is currently not documented in the form of books or papers. There fore, the world may lose most of this knowledge. Thus, we need a universal script which could be used as the default script for all languages which do not have their own script. Braille is a universal script; persons with blindness use this script to write all languages of the world. Under the Aegis of UNESCO, in 1949 through 1951, a project was undertaken to propose world Braille. This Braille unified Braille codes for most of the languages based on phonetic sounds. The History of Braille demonstrates that this script is readable by both, seeing and blind persons and is easy to learn and use. This script stood the test of time and evolved as the best system among many proposed systems throughout a period of centuries. Braille can pave way for development of the universal script. -

History of Braille Article

Title: History of Braille Article: Braille is a system of touch reading and writing for blind persons in which raised dots represent the letters of the alphabet. It also contains equivalents for punctuation marks and provides symbols to show letter groupings. Braille is read by moving the hand or hands from left to right along each line. The reading process usually involves both hands, and the index fingers generally do the reading. The average reading speed is about 125 words per minute. But greater speeds of up to 200 words per minute are possible. People who are blind can review and study the written word. They can also become aware of different written conventions such as spelling, punctuation, paragraphing, and footnotes. Most importantly, braille gives blind individuals access to a wide range of reading materials including recreational and educational reading, financial statements, and restaurant menus. Equally important are contracts, regulations, insurance policies, directories, and cookbooks that are all part of daily adult life. Through braille, people who are blind can also pursue hobbies and cultural enrichment with materials such as music scores, hymnals, playing cards, and board games. Various other methods had been attempted over the years to enable reading for the blind. However, many of them were raised versions of print letters. It is generally accepted that the braille system has succeeded because it is based on a rational sequence of signs devised for the fingertips, rather than imitating signs devised for the eyes. Night-Writing The history of braille goes all the way back to the early 1800s. -

Recognition of Documents in Braille

Recognition of Documents in Braille Dr Jomy John Assistant Professor Department of Computer Science K. K. T. M. Govt. College, Pullut, Kodungallur, Kerala [email protected] 1 INTRODUCTION Our society is diverse. There are people around us with vision impairment either partially or fully and people with hearing loss, people who unable to speak, people with inherent learning disability etc. Visually impaired people are integral part of the society and it has been a must to provide them with means and system through which they may communicate with the world. As of 2012 there were 285 million people who were visually impaired of which 246 million had low vision and 39 million were blind [1-2]. In this chapter, I would like to address how computers can be made useful to read the scripts in Braille. The importance of this work is to reduce communication gap between visually impaired people and the society. Braille remains the most 217 popular tactile reading code even in this century. There are numerous amount of literature locked up in Braille. Their literary work, graphics are hidden under a script that normally others will not read. This work will help in office automation with huge documents held up in Braille. Braille recognition not only reduces time in reading or extracting information from Braille document but also helps people engaged in special education for correcting papers and other school related works. The availability of such a system will enhance communication and collaboration possibilities with visually impaired people [3]. Even if blind people know how to use Braille script, it is not an easy method to communicate with normal people because they are Braille illiterate. -

Pengembangan Skala Sikap Diferensial Semantik

Inclusion Education: Learning Reading Arabic Language and AlQuran for Blind Submitted: 09 September 2019, Accepted: 26 December 2019 AL-BIDAYAH: Jurnal Pendidikan Dasar Islam ISSN: 2085-0034 (print), ISSN: 2549-3388 (online) INCLUSION EDUCATION: LEARNING READING ARABIC LANGUAGE AND ALQURAN FOR BLIND Rubini, Cahya Edi Setyawan STAI Masjid Syuhada Yogyakarta E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT Inclusive education is one of the priorities that must be considered for the sake of equality in educating the nation. Inclusive education is contained in the form of learning towards a group of people with special needs. Special needs in Indonesia are mostly those who have physical disabilities, one of the blind. This study aims to determine how the stages of learning to read Arabic letters and the Qur'an for the blind. This type of research is library research, with the method of collecting data, searching, analyzing, and synthesizing the latest research. The results of the study stages of learning to read Arabic letters and the Qur'an for the blind are: memorize Arabic Braille numeric codes from Alif memorizing Arabic punctuation, practice fingering Braille hijaiyah letters and ,ي to Ya أ Arabic punctuation, IQRA reading practice starting from words to simple sentences, and practice reading the Koran which starts from short letters to long letters. Keywords: inclusive education, Arabic literacy, visual impairment, blind people INTRODUCTION Inclusive Education in Indonesia is regulated in law number 20 of 2003 concerning the education system, which states that every citizen has the same right to obtain a quality education. In the 1945 Constitution, Article 32, paragraphs 1 and 2 also regulates, which emphasizes the right to education for citizens for primary school and is funded by the government. -

Japanese Braille Tutorial

Japanese Braille Tutorial By Mitsuji Kadota ([email protected]) Last update: 1997.10.20 Table of contents 1. Introduction 1.1 Difference in Japanese and English language 2. Transcribing Japanese sentence to Braille 2.1 Transcription from Kanji to Kana 2.2 Transcription from Kana to Braille 3. Japanse Braille 3.1 Normal characters 3.2 Daku-on 3.3 You-on 3.4 Tokusyu-on 3.5 Arabic numerals 3.6 Alpahbets 3.6 Other characters 4. Japanese sentence example 1. Introduction Braille system was invented by Louis Braille in 1825 and was established as the international standard in 1878. Japanese Braille system is based on Louis Braille's 6-dot system, and improved byKuraji Ishikawa. Ishikawa made Japanese Braille system fit to Japanese language. Phonological and orthographic difference in Japanese and English makes transcription process of Japanese Braille very unique. 1.1 Difference in Japanese and English language The noticeable phonological difference between Japanese and English is in syllable structure where English syllable is basically closed (CVC: a consonant + a vowel + a consonant) and Japanese syllable, open (CV). In terms of orthography, Japanese is written with Kanji, Kana (Hiragana and Katakana), western alphabet and Arabic numerals. Kanji is an ideogram imported from China and Kana is a phonogram created from Kanji by Japanese. While alphabet represents a single sound, Kana represents a syllable (a consonant and a vowel). Each Kanji can be transcribed by Kana's. Generally, Kanji's are used as independent words whereas Kana's, as function words. Since Japanese is written with a combination of Kanji and Kana, unlike English and other western languages, a space is not usually inserted between words. -

The Development of Education for Blind People

1 Chapter 1: The development of education for blind people The development of education for blind people Legacy of the Past The book Legacy of the Past (Some aspects of the history of blind educa- tion, deaf education, and deaf-blind education with emphasis on the time before 1900) contains three chapters: Chapter 1: The development of education for blind people Chapter 2: The development of education for deaf people Chapter 3: The development of education for deaf-blind people In all 399 pp. An internet edition of the whole book in one single document would be very unhandy. Therefore, I have divided the book into three documents (three inter- netbooks). In all, the three documents contain the whole book. Legacy of the Past. This Internetbook is Chapter 1: The development of education for blind people. Foreword In his Introduction the author expresses very clearly that this book is not The history of blind education, deaf education and deaf-blind education but some aspects of their history of education with emphasis on the time before 1900. Nevertheless - having had the privilege of reading it - my opinion is that this volume must be one of the most extensive on the market today regarding this part of the history of special education. For several years now I have had the great pleasure of working with the author, and I am not surprised by the fact that he really has gone to the basic sources trying to find the right answers and perspectives. Who are they - and in what ways have societies during the centuries faced the problems? By going back to ancient sources like the Bible, the Holy Koran and to Nordic Myths the author gives the reader an exciting perspective; expressed, among other things, by a discussion of terms used through our history. -

Quranic Braille System

World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology 46 2008 Quranic Braille System Abdallah M. Abualkishik, and Khairuddin Omar Abstract—This article concerned with the translation of Quranic Braille is the system of touch reading and writing which verses to Braille symbols, by using Visual basic program. The utilizes raised dots to represent the print alphabet letters for system has the ability to translate the special vibration for the Quran. persons who are blind. The Braille system also includes This study limited for the (Noun + Scoon) vibrations. It builds on an symbols to represent punctuation, mathematic and scientific existing translation system that combines a finite state machine with left and right context matching and a set of translation rules. This characters, music, computer notation, and foreign languages. allows to translate the Arabic language from text to Braille symbols By using of Braille symbols, the blind are able to review and after detect the vibration for the Quran verses. study the written word. It provides a vehicle for literacy and gives a blind the ability to become familiar with spelling, Keywords—Braille, Quran vibration, Finite State Machine. punctuation, paragraphing, footnotes, bibliographies and other formatting considerations. Braille cell is consist of 6 I. INTRODUCTION dots, 2 across and 3 down, is considered the basic unit for all OW will blind people participate in a literate culture? Braille symbols. For easier identification, these dots are H How will they continue their education? What make numbered downward 1, 2, 3 on the left, and 4, 5, and 6 on the them feel as the normal people? What about the Muslim blind right (see Fig.