Journal Issue #2 Journal Issue #2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Enemy Suede Underworld Non Phixion Mando Diao

Nummer 6 • 2002 Sveriges största musiktidning Death in Vegas Public Enemy Suede Underworld Non Phixion Mando Diao Chilly & Leafy • S.I. Futures • Moldy Peaches • Ex-girl • Steve Shelley Groove 6 • 2002 Ledare Omslag Death in Vegas av Johannes Giotas Groove Storleken har Box 112 91 Ex-girl sidan 5 404 26 Göteborg Tre frågor till Steve Shelley sidan 5 Telefon 031–833 855 Lätt att vara DJ sidan 5 visst betydelse Elpost [email protected] S.I. Futures sidan 6 http://www.groove.st Som vilken frisk sjuåring som att lägga ut låtar med demoband Allt är NME:s fel sidan 6 helst så växer Groove på höjden, vi tycker förtjänar fler lyssnare, en Chefredaktör & ansvarig utgivare Chilly & Leafy sidan 7 närmare bestämt 5,5 centimeter. unik chans att få höra ny och Gary Andersson, [email protected] Vi har så mycket material och spännande svensk musik. Och Ett subjektivt alfabet sidan 7 idéer att vi inte får plats i den snart levererar vi även konsert- Skivredaktör kvadratiska kostymen – dags att recensioner på hemsidan, något vi Björn Magnusson, [email protected] Mando Diao sidan 8 byta upp sig helt enkelt. Detta märkt att ni, våra läsare, vill ha. Mediaredaktör innebär utöver att våra artiklar Allt detta är, som man säger, Public Enemy sidan 10 Dan Andresson, [email protected] blir fylligare att antalet recensio- under uppbyggnad. Magisk dag i Suede sidan 13 ner ökar rejält (och ändå hittar du veckan kommer att bli måndagar, Layout Non Phixion sidan 14 ytterligare cirka 100 stycken på då släpps alltid någonting nytt. Henrik Strömberg, [email protected] vår hemsida www.groove.st). -

Software Crack

1 Foresights A glance into the crystal HE ORCH ball shows great things PMALSQJLLfc^^ for VU, city, page 10 2QQ3___ ymmJ&LM&Jk Tonight: Starry Night, 44° complete weather on pg. 2 SOFTWARE CRACK »• INSIDE EIS receives first complaint of copyright violations involving software News Becca Klusman only run a copy on a single machine, and two revenue for the company whose product has Legal Anniversary TORCH WRITER or more machines have copies with the same effectively been stolen. The VU violation, serial numbers, that, again, is convincing evi there was no exception. Electronic Information Services (EIS) dence of a violation," said Yohe. The accused student was sharing two received their first software copyright viola Adobe Products and one Macromedia product. tion complaint last week from the Business • • It is possible the The total cost of the programs, had they been Software Alliance (BSA). purchased via retail catalog, would have added "To this point, all the complaints had people running P2P up to $1,080. been related to music files," said Mike Yohe, software may be The only other time in VU history that a Executive Director of EIS. sharing private files software violation occurred was a number of According to their website, the BSA is years ago. EIS investigated an unusually high an organization dedicated to the promotion of without even knowing amount of outbound traffic on a faculty com School of Law celebrates a safe and legal digital world. They represent it." puter. some of the fastest growing digital companies 125 years of excellence MIKE YOHE The investigation revealed that the com in the world. -

Hallo Zusammen

Hallo zusammen, Weihnachten steht vor der Tür! Damit dann auch alles mit den Geschenken klappt, bestellt bitte bis spätestens Freitag, den 12.12.! Bei nachträglich eingehenden Bestellungen können wir keine Gewähr übernehmen, dass die Sachen noch rechtzeitig bis Weihnachten eintrudeln! Vom 24.12. bis einschließlich 5.1.04 bleibt unser Mailorder geschlossen. Ab dem 6.1. sind wir aber wieder für euch da. Und noch eine generelle Anmerkung zum Schluss: Dieser Katalog offeriert nur ein Bruchteil unseres Gesamtangebotes. Falls ihr also etwas im vorliegenden Prospekt nicht findet, schaut einfach unter www.visions.de nach, schreibt ein E-Mail oder ruft kurz an. Viel Spass beim Stöbern wünscht, Udo Boll (VISIONS Mailorder-Boss) NEUERSCHEINUNGEN • CDs VON A-Z • VINYL • CD-ANGEBOTE • MERCHANDISE • BÜCHER • DVDs ! CD-Angebote 8,90 12,90 9,90 9,90 9,90 9,90 12,90 Bad Astronaut Black Rebel Motorcycle Club Cave In Cash, Johnny Cash, Johnny Elbow Jimmy Eat World Acrophobe dto. Antenna American Rec. 2: Unchained American Rec. 3: Solitary Man Cast Of Thousands Bleed American 12,90 7,90 12,90 9,90 12,90 8,90 12,90 Mother Tongue Oasis Queens Of The Stone Age Radiohead Sevendust T(I)NC …Trail Of Dead Ghost Note Be Here Now Rated R Amnesiac Seasons Bigger Cages, Longer Chains Source Tags & Codes 4 Lyn - dto. 10,90 An einem Sonntag im April 10,90 Limp Bizkit - Significant Other 11,90 Plant, Robert - Dreamland 12,90 3 Doors Down - The Better Life 12,90 Element Of Crime - Damals hinterm Mond 10,90 Limp Bizkit - Three Dollar Bill Y’all 8,90 Polyphonic Spree - Absolute Beginner -Bambule 10,90 Element Of Crime - Die schönen Rosen 10,90 Linkin Park - Reanimation 12,90 The Beginning Stages Of 12,90 Aerosmith - Greatest Hits 7,90 Element Of Crime - Live - Secret Samadhi 12,90 Portishead - PNYC 12,90 Aerosmith - Just Push Play 11,90 Freedom, Love & Hapiness 10,90 Live - Throwing Cooper 12,90 Portishead - dto. -

March 22-27, 2018

MARCH 22-27, 2018 FACEBOOK.COM/WHATZUPFTWAYNE // WWW.WHATZUP.COM SPRING Left to right: Carrie Hart, Jacob Ganser, Bee Kagel SAXOPHONESALE ---------------------- Feature • Black & White -------------------- UNBELIEVABLE PRICES ON SAXOPHONES! Enterprising Artists By Steve Penhollow & White) where we’re just putting it together with UP what we have,” she said. “We’re building our own It all started as a senior project. walls, for example. We want to prove that we can It will likely grow into a regularly recurring series make an event like this work while spending as little TO % of distinctive events combining visual art, music and money as possible.” the performing arts. Ganser said a lot of artists and musicians with big Black & White, the first show in an initial four- plans are frustrated by lack of funds, so one of the show spring series, hap- goals of this endeavor OFF pens March 28 at the Mi- is to look for ways to chael Graves-designed circumvent that real or SELECT SAXOPHONES “Cube House,” located perceived roadblock – 60 at 10220 Circlewood by pooling resources, Drive in Fort Wayne. by fostering collabora- It will feature the art tions, by devising work- of Lauren Castleman, arounds, by seeking out Michael Ganser, Reg- previously untapped gie Johnson. Suzie Su- performance and exhi- raci, Sara Conrad, April bition spaces. Weller, Dee Dee Mor- Most gallery spaces row (and others) and plan exhibitions a year FINANCING musical performances in advance, he said. by the Sean Christian Parr Trio, But artists in their teens and AVAILABLE The Turn Signals (and others). BLACK & WHITE 20s don’t tend to think that far The title is an entreaty to 6 p.m. -

The Ithacan, 2002-01-31

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 2001-02 The thI acan: 2000/01 to 2009/2010 1-31-2002 The thI acan, 2002-01-31 Ithaca College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_2001-02 Recommended Citation Ithaca College, "The thI acan, 2002-01-31" (2002). The Ithacan, 2001-02. 17. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_2001-02/17 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 2000/01 to 2009/2010 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 2001-02 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Vol. 69, No. 16 THURSDAY ITHACA, N.Y. JANUARY 31, 2002 28 PAGES, FREE www. ithaca. ed u/ithacan The N(!~vspaper for the Ithaca College Community Seeing a new Olympic view Faculty : :· . ~ -:to consider Sophomore ending A+ helps broadcast BY KELLI B. GRANT Assistant News Editor Winter Games Valued at 4.3 on the grade point average scale, an A+ can boost even the most lack BY ELLEN R. STAPLETON luster GPA. News Editor -But at the Tuesday Faculty Council meet ing, members will discuss, and possibly vote Sophomore Sean Colahan has always on, a recommendation to eliminate the A+ all watched the Olympics on television from together. If Faculty Council approves the mea his home. sure, it will move on to the college's Acade But as the 2002 Winter Games get un mic Policies Committee for consideration. derway in Salt Lake City on Feb. 8, Cola Eliminating the A+ is the first of four rec han will be there to witness the ommendations made by the Faculty Council figure-skating and short-track speed-skat Committee on Grading Policies in December ing action. -

Middle Class Music in Suburban Nowhere Land: Emo and the Performance of Masculinity

MIDDLE CLASS MUSIC IN SUBURBAN NOWHERE LAND: EMO AND THE PERFORMANCE OF MASCULINITY Matthew J. Aslaksen A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Becca Cragin Angela Nelson ii Abstract Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Emo is an emotional form that attracts a great deal of ridicule from much of the punk and indie music communities. Emo is short for “emotional punk” or “emotional hardcore,” but because of the amount of evolution it has undergone it has become a very difficult genre to define. This genre is well known for its almost whiny sound and its preoccupation with relationship problems and emotional instability. As a result, it is seen by many within the more underground music community as an inauthentic emotionally indulgent form of music. Emo has also very recently become a form that has gained widespread mainstream media appeal with bands such as Dashboard Confessional, Taking Back Sunday, and My Chemical Romance. It is generally consumed by a younger teenaged to early college audience, and it is largely performed by suburban middle class artists. Overall, I have argued that emo represents challenge to conventional norms of hegemonic middle-class masculinity, a challenge which has come about as a result of feelings of discontent with the emotional repression of this masculinity. In this work I have performed multiple interviews that include both performers and audience members who participate in this type of music. The questions that I ask the subjects of my ethnographic research focus on the meaning of this particular performance to both the audience and performers. -

42656曲、85.5日、652.37 Gb

1 / 87ページ Rock 42656曲、85.5日、652.37 GB アーティスト アルバム 項目数 合計時間 A.F.I. Black Sails In The Sunset 12 46:11 The A.G's This Earth Sucks 34 58:13 Above Them Blueprint for a Better Time 11 36:42 Abrasive Wheels The Riot City Years 1981-1982 22 53:41 Abrasive Wheels When The Punks Go Marching In 22 53:41 The ABS Mentalenema 8 23:27 The ABS A Wop Bop A Loo Bop...Acough,Wheese,Fart! 40 2:13:05 The Academy Is Almost Here 10 32:56 Accidente Accidente 11 27:10 Accidente Amistad y Rebelión 10 25:10 Ace Bushy Striptease The Words That You Said Are Still Wet In My Head 14 23:15 Action Action Don't Cut Your Fabric To This Year's Fashion 13 50:26 Active Sac Kill All Humans 13 34:23 Active Sac Road Soda 14 37:12 ADD/C Busy Days 15 29:09 Adhesive From left to right 14 25:32 The Adicts The Complete Singles Collection 24 1:11:50 The Adicts This Is Your Life 21 54:06 Adolescents Adolescents 16 35:21 The Adorkables ...She Loves Me Not 12 37:15 The Adverts Cast Of Thousands 14 45:48 The Adverts Crossing The Red Sea With The Adverts 14 39:22 The Adverts Live At The Roxy 12 36:09 The Afghan Whigs Up In It 13 45:36 After School Special After School Special 14 29:03 After The Fall After The Fall 12 40:20 Against Me! Americans Abroad!!! Against Me!!! Live In London!!! 17 52:29 Against Me! As The Eternal Cowboy 11 25:08 Against Me! Crime, as Forgiven By Against Me! 6 18:22 Agent Orange Living in Darkness 16 44:53 Aiden Nightmare Anatomy 11 40:18 Airbag Ensamble Cohetes 14 34:27 Airbag Mondo Cretino (Remasterizado 2009) 18 35:06 Airbag ¿Quién mató a Airbag? 13 31:39 Aitches Stay In Bed 15 32:43 Rock 2 / 87ページ アーティスト アルバム 項目数 合計時間 The Alarm Declaration 12 46:09 The Alarm Eye Of The Hurricane 10 41:01 Alex Kerns The Future Ain't What It Used To Be 9 20:59 Alexisonfire Watch Out! 11 43:45 Algebra One The Keep Tryst E.P. -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5030

Stockton's news source since 1973 Maxiay Decemte 10,2001 The independent student newspaper of the Richard Stockton College of New Jersey Volurne 61 Number 11 Stockton Student arrested in Housing I robbery alumna Shaun Reilly County CrimeStoppers. motor vehicle in parking lot seven. Rodriguez The Argo When the Police arrested Smith, they also was arrested as a John Doe because he had no The Richard Stockton College Police have picked up Corey Dameo on trespassing and identification at the time of the arrest. He was battles charged James L. Smith with robbery. an outstanding warrant. Dameo is a student later found to be a 21-year-old male who had According to Stockton Police Chief Thomas that was banned from entering the housing just been released from the Atlantic County Kinzer, on October 26th a facilities. He was with Smith at the time of Justice Facility. The Stockton Police charged with AIDS non-student visiting others their arrest. He was also detained for an active Rodriguez with theft from a motor vehicle. Police in a Housing I apartment warrant for a motor vehicle violation in Dan Grote Bioner was accosted by Smith and Stafford Township. Drug and Alcohol Offenses The Argo an another assailant. The Rui D. Costa, a 20 year old student from The Office of Housing and assailants allegedly stole personal property On November 12, a caller reported to the Rowan University, was charged with posses Residential Life sponsored a pro and cash from the unnamed victim by both police that a suspicious person had aban sion of controlled and dangerous substances gram in recognition of World physical force and threats. -

November 7, 2007

STAFF EDITORIAL | KEEPING IT GREEN WITH BABY STEPS | SEE FORUM, PAGE 4 TUDENT IFE THE SINDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER OF WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY L IN ST. LOUIS SINCE 1878 VOLUME 129, NO. 31 WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 7, 2007 WWW.STUDLIFE.COM Engineering faculty petition for Dean Sansalone’s removal v Citing communication issues and controversial e-mail, tenured faculty unites BY SAM GUZIK Dean Sansalone to review the e- concerned in some sectors.” school of engineering have ex- SENIOR NEWS EDITOR mails and background behind The rift with faculty and stu- pressed frustration at the lack them,” wrote Chancellor Wrigh- dents has been compounded by of effective communication be- Just over a year into her ten- ton in an e-mail to Student Life. a perceived lack of communica- tween the administration and ure, engineering dean Mary “Dean Sansalone apologized tion over changes to the School the rest of the school regarding Sansalone has come under fi re for the unfortunate impression and by the perception that policy changes. for the methods she used in created by the e-mails.” Dean Sansalone’s actions are Many of Sansalone’s biggest implementing several contro- Of 66 tenured engineering unilateral. changes were implemented and versial changes in the School. faculty members, 29 signed the “The environment is one announced before signifi cant Many faculty members have petition and an additional 14 of terror, everyone is scared,” feedback could be received. expressed concern about an expressed their support verbal- said Bia Henriques, a graduate In many cases, contradictory e-mail from Dean Sansalone ly, according to sources within student. -

Saves the Day Stay What You Are Download

Saves the day stay what you are download LINK TO DOWNLOAD Sep 17, · Stay What You Are Featured On. Saves the Day Essentials Apple Music Alternative Albums You May Also Like. Cult Bayside Saves The Day, under exclusive license to Equal Vision Records, Inc. Also available in the iTunes Store More by Saves The Day. rows · Jan 01, · Listen free to Saves the Day – Stay What You Are (At Your Funeral, See . Oct 30, · DG02, , VR Saves The Day: Stay What You Are (CD, Album, Dig): Vagrant Records, Vagrant Records, Vagrant Records, B-Unique Records: DG02, , VR /5(). If you like guitar rock but are tired of Green Day-esque simplicity of sound and lyric and still want to hear notes and melodies rather than mere distortion and screaming, I highly recommend Stay What You Are. I don't find a skippable song on the album/5(). Stay What You Are is the third studio album from New Jersey emo band Saves the renuzap.podarokideal.rued on Vagrant Records, the album was the band’s largest commercial success; reaching the top-half of the. Buy Saves the Day - Stay What You Are vinyl LP at SRCVinyl. Vagrant Records. Jan 30, · Here goes a rendition the classic music critic gripe: If the world was a "just" place (oh silly critics) Saves the Day would have the career of Fall Out Boy, only with way more credibility. 's Stay What You Are is the most radio-ready emo album there is and it's not even that close. A Day Away. A Day To Remember. -

Edward J. Hackett Arrested on P Arole Violations Allegedly Resp Onsible Tor Rossignol's Death

EdwardJ. Hackett arrested on p arole violations Murder suspect has history of stalking allegedly responsible tor Rossignol's death parking lots, kidnap- By KAITLIN McCArTERTY on parole to his parents' home ping, sexual assau t and UZ BOMZE in Vassalboro, Me, after EDITOR-IN-CHIEF AND pleading guilty to burglary MANAGING EDITOR and kidnapping in Salt Lake By LIZ BOMZE City, Utah and serving nine MANAGING EDITOR State Police announced at a press years of his 1994 sentence conference on Tuesday in the Alfond [see article, pg. 1]. More than 11 years ago, Salt Athletic Center that the man respon- Police report no connection Lake City, Utah police arrested and sible for the murder of Dawn between Hackett and charged Edward J. Hackett, Dawn Rossignol '04 last week has been Rossignol or Colby College. Rossignol's '04 alleged killer, for arrested on parole violations. Lt. Doyle said, "This was a ran- attacking a 24-year-old woman at Timothy Doyle of the State Police dom act of violence. Colby knifepoint at a Salt Lake City park- said that he expects the Attorney College could have been any ing terrace. General to charge Hackett with mur- parking lot at any facility in According to the "Salt Lake der within the week. Maine. There was no associa- Tribune," Hackett, who was 37 at "A one-week investigation into the tion between Ed Hackett and the time of the prior assault, kid- , ' HTTP://WWW.WMmCOM/GLOBAL/STORY.ASP?S=145<!146&NAV=7K6RI97D napped the victim at 9:30 p.m. on a death of Dawn Rossignol which Dawn Rossignol—the two Edward J. -

Order Form Full

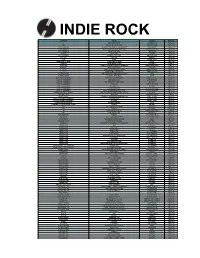

INDIE ROCK ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL 68 TWO PARTS VIPER COOKING VINYL RM128.00 *ASK DISCIPLINE & PRESSURE GROUND SOUND RM100.00 10, 000 MANIACS IN THE CITY OF ANGELS - 1993 BROADC PARACHUTE RM151.00 10, 000 MANIACS MUSIC FROM THE MOTION PICTURE ORIGINAL RECORD RM133.00 10, 000 MANIACS TWICE TOLD TALES CLEOPATRA RM108.00 12 RODS LOST TIME CHIGLIAK RM100.00 16 HORSEPOWER SACKCLOTH'N'ASHES MUSIC ON VINYL RM147.00 1975, THE THE 1975 VAGRANT RM140.00 1990S KICKS ROUGH TRADE RM100.00 30 SECONDS TO MARS 30 SECONDS TO MARS VIRGIN RM132.00 31 KNOTS TRUMP HARM (180 GR) POLYVINYL RM95.00 400 BLOWS ANGEL'S TRUMPETS & DEVIL'S TROMBONE NARNACK RECORDS RM83.00 45 GRAVE PICK YOUR POISON FRONTIER RM93.00 5, 6, 7, 8'S BOMB THE ROCKS: EARLY DAYS SWEET NOTHING RM142.00 5, 6, 7, 8'S TEENAGE MOJO WORKOUT SWEET NOTHING RM129.00 A CERTAIN RATIO THE GRAVEYARD AND THE BALLROOM MUTE RM133.00 A CERTAIN RATIO TO EACH... (RED VINYL) MUTE RM133.00 A CITY SAFE FROM SEA THROW ME THROUGH WALLS MAGIC BULLET RM74.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER BAD VIBRATIONS ADTR RECORDS RM116.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER FOR THOSE WHO HAVE HEART VICTORY RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER HOMESICK VICTORY RECORDS RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD VICTORY RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD (PIC) VICTORY RECORDS RM111.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER WHAT SEPARATES ME FROM YOU VICTORY RECORDS RM101.00 A GREAT BIG PILE OF LEAVES HAVE YOU SEEN MY PREFRONTAL CORTEX? TOPSHELF RM103.00 A LIFE ONCE LOST IRON GAG SUBURBAN HOME RM99.00 A MINOR FOREST FLEMISH ALTRUISM/ININDEPENDENCE (RS THRILL JOCKEY RM135.00 A PLACE TO BURY STRANGERS TRANSFIXIATION DEAD OCEANS RM102.00 A PLACE TO BURY STRANGERS WORSHIP DEAD OCEANS RM102.00 A SUNNY DAY IN GLASGOW SEA WHEN ABSENT LEFSE RM101.00 A WINGED VICTORY FOR THE SULLEN ATOMOS KRANKY RM128.00 A.F.I.