The In/Visible Woman: Mariangela Ardinghelli and the Circulation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hubert Kennedy Eight Mathematical Biographies

Hubert Kennedy Eight Mathematical Biographies Peremptory Publications San Francisco 2002 © 2002 by Hubert Kennedy Eight Mathematical Biographies is a Peremptory Publications ebook. It may be freely distributed, but no changes may be made in it. Comments and suggestions are welcome. Please write to [email protected] . 2 Contents Introduction 4 Maria Gaetana Agnesi 5 Cesare Burali-Forti 13 Alessandro Padoa 17 Marc-Antoine Parseval des Chênes 19 Giuseppe Peano 22 Mario Pieri 32 Emil Leon Post 35 Giovanni Vailati 40 3 Introduction When a Dictionary of Scientific Biography was planned, my special research interest was Giuseppe Peano, so I volunteered to write five entries on Peano and his friends/colleagues, whose work I was investigating. (The DSB was published in 14 vol- umes in 1970–76, edited by C. C. Gillispie, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.) I was later asked to write two more entries: for Parseval and Emil Leon Post. The entry for Post had to be done very quickly, and I could not have finished it without the generous help of one of his relatives. By the time the last of these articles was published in 1976, that for Giovanni Vailati, I had come out publicly as a homosexual and was involved in the gay liberation movement. But my article on Vailati was still discreet. If I had written it later, I would probably have included evidence of his homosexuality. The seven articles for the Dictionary of Scientific Biography have a uniform appear- ance. (The exception is the article on Burali-Forti, which I present here as I originally wrote it—with reference footnotes. -

New Working Papers Series, Entitled “Working Papers in Technology Governance and Economic Dynamics”

Working Papers in Technology Governance and Economic Dynamics no. 74 the other canon foundation, Norway Tallinn University of Technology, Tallinn Ragnar Nurkse Department of Innovation and Governance CONTACT: Rainer Kattel, [email protected]; Wolfgang Drechsler, [email protected]; Erik S. Reinert, [email protected] 80 Economic Bestsellers before 1850: A Fresh Look at the History of Economic Thought Erik S. Reinert, Kenneth Carpenter, Fernanda A. Reinert, Sophus A. Reinert* MAY 2017 * E. Reinert, Tallinn University of Technology & The Other Canon Foundation, Norway; K. Car- penter, former librarian, Harvard University; F. Reinert, The Other Canon Foundation, Norway; S. Reinert, Harvard Business School. The authors are grateful to Dr. Debra Wallace, Managing Director, Baker Library Services and, Laura Linard, Director of Baker Library Special Collections, at Harvard Business School, where the Historical Collection now houses what was once the Kress Library, for their cooperation in this venture. Above all our thanks go to Olga Mikheeva at Tallinn University of Technology for her very efficient research assistance. Antiquarian book dealers often have more information on economics books than do academics, and our thanks go to Wilhelm Hohmann in Stuttgart, Robert H. Rubin in Brookline MA, Elvira Tasbach in Berlin, and, above all, to Ian Smith in London. We are also grateful for advice from Richard van den Berg, Francesco Boldizzoni, Patrick O’Brien, Alexandre Mendes Cunha, Bertram Schefold and Arild Sæther. Corresponding author [email protected] The core and backbone of this publication consists of the meticulous work of Kenneth Carpenter, librarian of the Kress Library at Harvard Busi- ness School starting in 1968 and later Assistant Director for Research Resources in the Harvard University Library and the Harvard College 1 Library. -

Catholic Christian Christian

Religious Scientists (From the Vatican Observatory Website) https://www.vofoundation.org/faith-and-science/religious-scientists/ Many scientists are religious people—men and women of faith—believers in God. This section features some of the religious scientists who appear in different entries on these Faith and Science pages. Some of these scientists are well-known, others less so. Many are Catholic, many are not. Most are Christian, but some are not. Some of these scientists of faith have lived saintly lives. Many scientists who are faith-full tend to describe science as an effort to understand the works of God and thus to grow closer to God. Quite a few describe their work in science almost as a duty they have to seek to improve the lives of their fellow human beings through greater understanding of the world around them. But the people featured here are featured because they are scientists, not because they are saints (even when they are, in fact, saints). Scientists tend to be creative, independent-minded and confident of their ideas. We also maintain a longer listing of scientists of faith who may or may not be discussed on these Faith and Science pages—click here for that listing. Agnesi, Maria Gaetana (1718-1799) Catholic Christian A child prodigy who obtained education and acclaim for her abilities in math and physics, as well as support from Pope Benedict XIV, Agnesi would write an early calculus textbook. She later abandoned her work in mathematics and physics and chose a life of service to those in need. Click here for Vatican Observatory Faith and Science entries about Maria Gaetana Agnesi. -

Maria Gaetana Agnesi Melissa De La Cruz

Maria Gaetana Agnesi Melissa De La Cruz Maria Gaetana Agnesi's life Maria Gaetana Agnesi was born on May 16, 1718. She also died on January 9, 1799. She was an Italian mathematician, philosopher, theologian, and humanitarian. Her father, Pietro Agnesi, was either said to be a wealthy silk merchant or a mathematics professor. Regardless, he was well to do and lived a social climber. He married Anna Fortunata Brivio, but had a total of 21 children with 3 female relations. He used his kids to be known with the Milanese socialites of the time and Maria Gaetana Agnesi was his oldest. He hosted soires and used his kids as entertainment. Maria's sisters would perform the musical acts while she would present Latin debates and orations on questions of natural philosophy. The family was well to do and Pietro has to make sure his children were under the best training to entertain well at these parties. For Maria, that meant well-esteemed tutors would be given because her father discovered her great potential for an advanced intellect. Her education included the usual languages and arts; she spoke Italian and French at the age of 5 and but the age of 11, she also knew how to speak Greek, Hebrew, Spanish, German and Latin. Historians have given her the name of the Seven-Tongued Orator. With private tutoring, she was also taught topics such as mathematics and natural philosophy, which was unusual for women at that time. With the Agnesi family living in Milan, Italy, Maria's family practiced religion seriously. -

Le Pour Et Le Contre. Galiani, La Diplomatie Et Le Commerce Des Blés

Le pour et le contre. Galiani, la diplomatie et le commerce des blés « Il y a quelque subalterne à Naples qui méritent d’être observé, entre autres l’abbé Galiani, qui aspire à jouer un rôle et croit se faire un mérite en s’opposant de tout son petit pouvoir à ce qui intéresse la France. »1 La plupart des études sur l’abbé Galiani, et particulièrement sur ses Dialogues sur le commerce des blés et sa période parisienne, oscillent entre trois grands pôles : l’histoire littéraire2, l’histoire de la pensée économique3; et l’histoire culturelle des Lumières et des sociabilités4. Ces études fondamentales ont ainsi éclairé les liens intellectuels de Galiani avec les écrivains et philosophes (en particulier Diderot et Grimm), le contenu théorique de sa pensée économique, et son inscription dans les cercles mondains de la capitale française. Cependant, une dimension d’importance semble négligée : l’activité diplomatique de l’abbé, qui ne peut être traitée séparément du reste. En effet, non seulement la « république des lettres » était encastrée dans le jeu du pouvoir, mais Ferdinando Galiani avait pour propriété sociale éminente d’être le chargé d’affaire du Royaume des Deux-Siciles, chargé d’informer le gouvernement de son royaume sur le cours des négociations du Pacte de Famille. Sa présence assidue dans les salons parisiens ne témoigne pas seulement de son goût pour la bonne compagnie et la conversation mondaine, mais de son professionnalisme : hors Versailles, nul espace plus propice, en effet, à la fréquentation des grands5. Si le terme diplomate apparaît tardivement, sous la Révolution semble-t-il, pour désigner le métier de représentant d’une puissance étrangère, la réalité professionnelle lui est antérieure6. -

Cavendish the Experimental Life

Cavendish The Experimental Life Revised Second Edition Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge Series Editors Ian T. Baldwin, Gerd Graßhoff, Jürgen Renn, Dagmar Schäfer, Robert Schlögl, Bernard F. Schutz Edition Open Access Development Team Lindy Divarci, Georg Pflanz, Klaus Thoden, Dirk Wintergrün. The Edition Open Access (EOA) platform was founded to bring together publi- cation initiatives seeking to disseminate the results of scholarly work in a format that combines traditional publications with the digital medium. It currently hosts the open-access publications of the “Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge” (MPRL) and “Edition Open Sources” (EOS). EOA is open to host other open access initiatives similar in conception and spirit, in accordance with the Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the sciences and humanities, which was launched by the Max Planck Society in 2003. By combining the advantages of traditional publications and the digital medium, the platform offers a new way of publishing research and of studying historical topics or current issues in relation to primary materials that are otherwise not easily available. The volumes are available both as printed books and as online open access publications. They are directed at scholars and students of various disciplines, and at a broader public interested in how science shapes our world. Cavendish The Experimental Life Revised Second Edition Christa Jungnickel and Russell McCormmach Studies 7 Studies 7 Communicated by Jed Z. Buchwald Editorial Team: Lindy Divarci, Georg Pflanz, Bendix Düker, Caroline Frank, Beatrice Hermann, Beatrice Hilke Image Processing: Digitization Group of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Cover Image: Chemical Laboratory. -

Encountering the Enlightenment: Science, Religion, and Catholic Epistemologies Across the Spanish Atlantic, 1687-1813

Encountering the Enlightenment: Science, Religion, and Catholic Epistemologies across the Spanish Atlantic, 1687-1813 by Copyright 2016 George Alan Klaeren Submitted to the graduate degree program in History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________ Chairperson Dr. Luis Corteguera _______________________________ Dr. Elizabeth Kuznesof _______________________________ Dr. Robert Schwaller _______________________________ Dr. Marta Vicente _______________________________ Dr. Santa Arias Date Defended: February 23, 2017 ii The Dissertation Committee for George Alan Klaeren certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Encountering the Enlightenment: Science, Religion, and Catholic Epistemologies across the Spanish Atlantic, 1687-1813 _________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Luis Corteguera Date approved: February 23, 2017 iii ABSTRACT During the eighteenth century, a wave of thought inundated the Spanish empire, introducing new knowledge in the natural sciences, religion, and philosophy, and importantly, questioning the very modes of perceiving and ascertaining this knowledge. This period of epistemic rupture in Spain and her colonies, commonly referred to as the Enlightenment, not only presented new ways of knowing, but inspired impassioned debates among leading intellectuals about the epistemology and philosophy that continued throughout the century. The previous scholarly literature -

Public Happiness As the Wealth of Nations: the Rise of Political Economy in Naples in a Comparative Perspective

Public Happiness as the Wealth of Nations: The Rise of Political Economy in Naples in a Comparative Perspective Filippo Sabetti The professed object of Dr. Adam Smith’ inquiry is the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. There is another inquiry, however, perhaps still more interesting, which he occasionally mixes with it, I mean an inquiry into the causes which affect the happiness of nations. (Malthus 1798: 303, quoted in Bruni and Porta 2005, 1) The rise of political economy in eighteenth-century Naples was as much a response to the economic conditions of the realm as it was an effort to absorb, modify, and give a hand to the scientific and human progress agitating Transalpine currents of thought. The emerging political economy in Naples stands out in part because its calls for reform and for the creation of a commercial and manufacturing society were not a radical break or rupture with the past. The recognition of the capacity of a commercial society to create wealth was accompanied by the equally important recognition that market transactions between individuals could be perceived both as mutually beneficial exchanges and as genuine social interactions that carried moral value by virtue of the social content. Whereas the Scottish Enlightenment sought to isolate market relationships from other relationships and to separate the concept of a well-governed state from the ideal of the virtuous citizen, the Neapolitan Enlightenment continued to embed the economy in social relations, arguing that good institutions could not function in the absence of good men. Individual happiness was derived from making others happy and not from the accumulation of things. -

MG Agnesi, R. Rampinelli and the Riccati Family

Historia Mathematica 42 (2015): 296-314 DOI 10.1016/j.hm.2014.12.001 __________________________________________________________________________________ M.G. Agnesi, R. Rampinelli and the Riccati Family: A Cultural Fellowship Formed for an Important Scientific Purpose, the Instituzioni analitiche CLARA SILVIA ROERO Department of Mathematics G. Peano, University of Torino, Italy1 Not every learned man makes a good teacher, nor is he able to transmit to others what he knows. Rampinelli, however, was marvellously endowed with this talent. [Brognoli, 1785, 85]2 1. Introduction “Shortly after I arrived in Milan I had the pleasure of meeting Signora Countess Donna Maria Agnesi who was well versed in the Latin and Greek languages, and even Hebrew, as well as other more familiar tongues; moreover, she was well educated in the most important Metaphysics, the Physics of the day and Geometry, and she knew enough of Mechanics for the purposes of Physics; she had a little knowledge of Cartesian algebra, but all self-acquired as there was no one here who could enlighten her. Therefore she asked me to assist her in that study, to which I agreed, and in a short time she had, with extraordinary strength and depth of talent, wonderfully mastered Cartesian algebra and the two infinitesimal Calculi,3 to which she added the application of these to the most lofty physical matters. I assure you that I have always been and still am amazed by seeing such talent and such depth of knowledge in a woman as would be remarkable in a man, and in particular by seeing this accompanied by quite remarkable Christian virtue.”4 On 9 June 1745, Ramiro Rampinelli (1697-1759) thus presented to his main scientific interlocutor of the time, Giordano Riccati (1709-1790), the talents of his Milanese pupil 1 Financial support of MIUR, PRIN 2009 “Mathematical Schools and National Identity in Modern and Contemporary Italy”, unit of Torino. -

Giovanni Battista Doni (1594- 1647) and the Dispute on Roman Air

Wholesome or Pestilential? Giovanni Battista Doni (1594- 1647) and the Dispute on Roman Air 1. Introduction In the early modern period, environmental discourse pervaded multiple disciplinary fields, from medicine to literature, from political thought to natural philosophy. It was also fraught with tensions and precarious negotiations between tradition and innovation, as ancient authorities were read and reinterpreted through the lens of new conceptual frameworks. This article draws attention to the divided and divisive nature of early modern environmental discourse by focusing on a specific case study: the dispute over the (alleged) insalubrity of Roman air that took place in Italy from the late sixteenth century to the early eighteenth century, reactivating, as we shall see, ancient controversies on the same topic. Within a span of about a century and a half, such a dispute generated a number of Latin and vernacular writings, authored by some of the most respected physicians and intellectuals of the time.1 With the exception of Giovanni Battista Doni (1594-1647), a Florentine nobleman and polymath best known for his musicological studies,2 all of the authors involved in this dispute were Roman-based physicians, often connected to each other by demonstrable personal ties. For instance, the Veronese Marsilio Cagnati (1543-1612) studied at the Roman school of Alessandro Traiano Petronio (?-1585), and referred to his master’s work frequently, though critically, in his treatise of 1599; Tommaso De Neri (c. 1560-?), from Tivoli (near Rome), -

Science As a Career in Enlightenment Italy: the Strategies of Laura Bassi Author(S): Paula Findlen Source: Isis, Vol

Science as a Career in Enlightenment Italy: The Strategies of Laura Bassi Author(s): Paula Findlen Source: Isis, Vol. 84, No. 3 (Sep., 1993), pp. 441-469 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of The History of Science Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/235642 . Accessed: 20/03/2013 19:41 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and The History of Science Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Isis. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 149.31.21.88 on Wed, 20 Mar 2013 19:41:48 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Science as a Career in Enlightenment Italy The Strategies of Laura Bassi By Paula Findlen* When Man wears dresses And waits to fall in love Then Womanshould take a degree.' IN 1732 LAURA BASSI (1711-1778) became the second woman to receive a university degree and the first to be offered an official teaching position at any university in Europe. While many other women were known for their erudition, none received the institutional legitimation accorded Bassi, a graduate of and lecturer at the University of Bologna and a member of the Academy of the Institute for Sciences (Istituto delle Scienze), where she held the chair in experimental physics from 1776 until her death in 1778. -

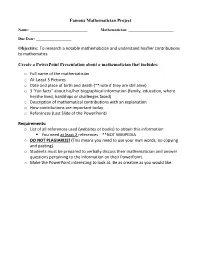

Famous Mathematician Project Objective: to Research a Notable

Famous Mathematician Project Name: _____________________________ Mathematician: _______________________ Due Date: __________________ Objective: To research a notable mathematician and understand his/her contributions to mathematics. Create a PowerPoint Presentation about a mathematician that includes: o Full name of the mathematician o At Least 3 Pictures o Date and place of birth and death (**note if they are still alive) o 3 “fun facts” about his/her biographical information (family, education, where he/she lived, hardships or challenges faced) o Description of mathematical contributions with an explanation o How contributions are important today o References (Last Slide of the PowerPoint) Requirements: o List of all references used (websites or books) to obtain this information ▪ You need at least 2 references **NOT WIKIPEDIA o DO NOT PLAGIARIZE! (This means you need to use your own words; no copying and pasting) o Students must be prepared to verbally discuss their mathematician and answer questions pertaining to the information on their PowerPoint. o Make the PowerPoint interesting to look at. Be as creative as you would like. Early mathematicians BC 1. Pythagoras - 2. Euclid - 3. Archimedes - 4. Hypatia of Alexandria - 0 - 1799 1. al-Khowârizmi - 2. Leonardo Fibonacci of Pisa - 3. Leonardo da Vinci - 4. Blaise Pascal - 5. Leonhard Euler - 6. Maria Gaetana Agnesi - 7. René Déscartes - 8. Carl F. Gauss - 9. Pierre de Fermat - 10. Gabrielle Émilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil - 11. Joseph-Louis Lagrange - 12. Isaac Newton - 13. Emilie du Chatelet - 14. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz - 15. Charles Babbage - 16. Augustin Louis Cauchy - 17. Joseph Fourier - 18. Daniel Bernoulli - 1800s 1. Ada Lovelace - 2. Sophie Germain - 3.