The Emergence of the New Anarchism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Social and Political Thought of Paul Goodman

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1980 The aesthetic community : the social and political thought of Paul Goodman. Willard Francis Petry University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Petry, Willard Francis, "The aesthetic community : the social and political thought of Paul Goodman." (1980). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2525. https://doi.org/10.7275/9zjp-s422 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DATE DUE UNIV. OF MASSACHUSETTS/AMHERST LIBRARY LD 3234 N268 1980 P4988 THE AESTHETIC COMMUNITY: THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL THOUGHT OF PAUL GOODMAN A Thesis Presented By WILLARD FRANCIS PETRY Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 1980 Political Science THE AESTHETIC COMMUNITY: THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL THOUGHT OF PAUL GOODMAN A Thesis Presented By WILLARD FRANCIS PETRY Approved as to style and content by: Dean Albertson, Member Glen Gordon, Department Head Political Science n Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.Org/details/ag:ptheticcommuni00petr . The repressed unused natures then tend to return as Images of the Golden Age, or Paradise, or as theories of the Happy Primitive. We can see how great poets, like Homer and Shakespeare, devoted themselves to glorifying the virtues of the previous era, as if it were their chief function to keep people from forgetting what it used to be to be a man. -

Université Du Québec À Montréal Paul Goodman Comme Sociothérapeute : Étude De Cas Sur La Dimension Politique De La Psycha

UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL PAUL GOODMAN COMME SOCIOTHÉRAPEUTE : ÉTUDE DE CAS SUR LA DIMENSION POLITIQUE DE LA PSYCHANALYSE MÉMOIRE PRÉSENTÉ COMME EXIGENCE PARTIELLE DE LA MAÎTRlSE EN HISTOIRE PAR JEAN-BAPTISTE LAMARCHE JANVIER 2007 UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL Service des bibliothèques Avertissement La diffusion de ce mémoire se fait dans le respect des droits de son auteur, qui a signé le formulaire Autorisation de reproduire et de diffuser un travail de recherche de cycles supérieurs (SDU-522 - Rév.01-2006). Cette autorisation stipule que «conformément à l'article 11 du Règlement no 8 des études de cycles supérieurs, [l'auteur] concède à l'Université du Québec à Montréal une licence non exclusive d'utilisation et de publication oe la totalité ou d'une partie importante de [son] travail de recherche pour des fins pédagogiques et non commerciales. Plus précisément, [l'auteur] autorise l'Université du Québec à Montréal à reproduire, diffuser, prêter, distribuer ou vendre des copies de [son] travail de recherche à des fins non commerciales sur quelque support que ce soit, y compris l'Internet. Cette licence et cette autorisation n'entraînent pas une renonciation de [la] part [de l'auteur] à [ses] droits moraux ni à [ses] droits de propriété intellectuelle. Sauf entente contraire, [l'auteur] conserve la liberté de diffuser et de commercialiser ou non ce travail dont [il] possède un exemplaire.» Remerciements Je voudrais ici remercier François Chanel, pour m'avoir si généreusement ouvert les portes du Centre de documentation de l'Association québécoise de Gestalt. Merci également à mes directeurs, Greg Robinson, professeur d'histoire à l'UQÀM, et Othmar Keel, professeur d'histoire à l'Université de Montréal, pour les commentaires et suggestions qu'ils m'ont prodigués tout au long de ce travail. -

“For a World Without Oppressors:” U.S. Anarchism from the Palmer

“For a World Without Oppressors:” U.S. Anarchism from the Palmer Raids to the Sixties by Andrew Cornell A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Social and Cultural Analysis Program in American Studies New York University January, 2011 _______________________ Andrew Ross © Andrew Cornell All Rights Reserved, 2011 “I am undertaking something which may turn out to be a resume of the English speaking anarchist movement in America and I am appalled at the little I know about it after my twenty years of association with anarchists both here and abroad.” -W.S. Van Valkenburgh, Letter to Agnes Inglis, 1932 “The difficulty in finding perspective is related to the general American lack of a historical consciousness…Many young white activists still act as though they have nothing to learn from their sisters and brothers who struggled before them.” -George Lakey, Strategy for a Living Revolution, 1971 “From the start, anarchism was an open political philosophy, always transforming itself in theory and practice…Yet when people are introduced to anarchism today, that openness, combined with a cultural propensity to forget the past, can make it seem a recent invention—without an elastic tradition, filled with debates, lessons, and experiments to build on.” -Cindy Milstein, Anarchism and Its Aspirations, 2010 “Librarians have an ‘academic’ sense, and can’t bare to throw anything away! Even things they don’t approve of. They acquire a historic sense. At the time a hand-bill may be very ‘bad’! But the following day it becomes ‘historic.’” -Agnes Inglis, Letter to Highlander Folk School, 1944 “To keep on repeating the same attempts without an intelligent appraisal of all the numerous failures in the past is not to uphold the right to experiment, but to insist upon one’s right to escape the hard facts of social struggle into the world of wishful belief. -

The Anarchist Writings of Paul Goodman

Library.Anarhija.Net Redrawing The Line: The Anarchist Writings of Paul Goodman Paul Comeau Spring, 2012 A review of Drawing The Line Once Again: Paul Goodman’s Anar- chist Writings, PM Press, 2010, 122 pages, trade paper- back, $14.95 While relatively unknown today, Paul Goodman was one of the most influential thinkers of the 20th century. In books like Growing Paul Comeau Up Absurd, published in 1960, Goodman captured the zeitgeist of Redrawing The Line: The Anarchist Writings of Paul Goodman his era, catapulting himself to the forefront of American intellectual Spring, 2012 life as one of the leading dissident thinkers inspiring the burgeoning New Left. FIFTH ESTATE #386, Spring, 2012, Vol. 47, No. 1, page 28 Goodman, who passed away in 1972 at the age of 60, was an iconoclastic radical with a wide ranging scope of intellectual vision lib.anarhija.net and a multi-faceted character. He was an anarchist, a family man, openly bisexual in a sexually repressive era, a psychologist (one of the founders of Gestalt Therapy), and a poet. He saw himself asa to new understanding. Where much political writing today drowns classical man of letters, and at his peak output, released nearly a readers in jargon, or assumes levels of advanced scholarship, Good- book a year. man’s writing has the potential to reach a wider and more diverse PM Press has recently reprinted some of Goodman’s writings in audience, giving strength to his ideas that other equally intelligent three volumes. The first, Drawing The Line Once Again: PaulGood- writers might lack. -

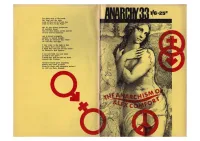

The Anarchism of Alex Comfort

[front cover] ANARCHY 33 1/6•25c THE ANARCHISM OF ALEX COMFORT [inside front cover] Contents of No. 33 No e!"e# 1$63 The Anarchism of Alex Comfort John Ellerby 329 Sex, Kicks and Comfort Charles Radcliffe 340 Alex Comfort’s Art and Scope Harold Drasdo 345 A Comfort Bibliography 357 A Disappointed Revolutionary Sid Parker 359 Cover by Rufus Segar Drawing on p. 329 by Frank Benier Poem “Maturity” by Alex Comfort from Haste to the Wedding (Eyre and Spottiswoode 1962) Other issues of ANARCHY 1. Sex-and-Violence; Galbraith; the New Wave, Education. 2. Workers’ Control. 3. What does anarchism mean today?; Africa; the Long Revolution. 4. De-institutionalisation; Conflicting strains in anarchism. 5. 1936: the Spanish Revolution. 6. Anarchy and the Cinema. (out of print) 7. Adventure Playgrounds. 8. Anarchists and Fabians; Action Anthropology; Eroding Capitalism. 9. Prison. 10. Sillitoe’s Key to the Door; Macinnes on Crime; Augustus John’s Utopia; Committee of 100. 11. Paul Goodman; Neill on Education; the Character-Builders. 12. Who are the anarchists? 13. Direct Action. (out of print) 14. Disobedience. 15. The work of David Wills. 16. Ethics of anarchism; Africa; Anthropology; Poetry of Dissent. 17. Towards a lumpenproletariat; Education vs. the working class; Freedom of access; Benevolent bureaucracy; CD and CND. 18. Comprehensive Schools. 19. Theatre: anger and anarchy. 20. Non-violence as a reading of history; Freud, anarchism and experiments in living. 21. Secondary modern. 22. Cranston’s Dialogue on anarchy. 23. Housing; Squatters; Do it yourself. 24. The Community of Scholars. 25. Technology, science, anarchism. 26. -

Paul Goodman, 1970, New Reformation

NEW REFORMATION NOTES of a NEOLITHIC CONSERVATIVE oc?id=10400622&ppg=1 formation : Notes of a Neolithic Conservative (2nd Edition). "His pleading, sane, frank, troubled and by now tired voice /dominicanuc/D is one of the truest and wisest in American life." -KENNETH KENISTON, NEW YORK TIMES Goodman, Paul (Author). New Re Oakland, CA, USA: PM Press, 2010. p i. 2010. Press, PM USA: CA, Oakland, http://site.ebrary.com/lib New Reformation Notes of a Neolithic Conservative Paul Goodman oc?id=10400622&ppg=2 formation : Notes of a Neolithic Conservative (2nd Edition). /dominicanuc/D Goodman, Paul (Author). New Re Oakland, CA, USA: PM Press, 2010. p 1. 2010. Press, PM USA: CA, Oakland, http://site.ebrary.com/lib The New Reformation: Notes of a Neolithic Conservative The New Reformation� 2010 by Sally Goodman Introduction 102010 by Michael C. Fisher This edition © 2010 by PM Press All rights reserved. No part of this book may be transmittedby any means without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN: 978-1-60486-056-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2009901372 Cover: John Yates Interior design by briandesign PM Press oc?id=10400622&ppg=3 PO Box 23912 Oakland, CA 94623 formation : Notes of a Neolithic Conservative (2nd Edition). www.pmpress.org Printed in the USA on recycled paper. /dominicanuc/D Goodman, Paul (Author). New Re Oakland, CA, USA: PM Press, 2010. p 2. 2010. Press, PM USA: CA, Oakland, http://site.ebrary.com/lib Contents Introduction by Michael C. Fisher 5 Preface 31 PART ONE Sciences and Professions Chapter 1 37 Chapter 2 53 Chapter 3 61 Chapter 4 70 PART TWO Education of the Young Chapter 5 85 Chapter 6 104 Chapter 7 112 Chapter 8 118 PART THREE Legitimacy Chapter 9 129 Chapter 10 143 Chapter 11 160 Chapter 12 170 oc?id=10400622&ppg=4 PART FOUR Notes of a Neolithic Conservative formation : Notes of a Neolithic Conservative (2nd Edition). -

What Is the Meaning of Life?

What is the Meaning of Life? Alan N. Shapiro On September 13, 2011, I gave a speech called “What is the Meaning of Life?” at the Plektrum Festival for Electronic Culture in Tallinn, Estonia. Plektrum Festival 2011 http://www.plektrumfestival.ee/ There were about 150 people in the audience. I spoke for almost two hours, mostly extemporaneously. Afterwards, there was a long question-and-answer session. There were some truly brilliant questions. I was especially impressed by one young man, who wondered if my critique of “binary oppositions” did not run the risk of itself instituting a binary opposition between my critique and the dualisms that I criticize. I said that he was right. We need an extremely subtle and sensitive epistemology to deal with such realities, with the real transformation that we seek. It is not easy to change the world. Below are my lecture notes for the Tallinn performance. I intersperse some headlines from my PowerPoint presentation. Douglas Adams, “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” A group of hyper-intelligent beings ask the supercomputer “Deep Thought” for the Ultimate Answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything It takes Deep Thought 7-1/2 million years to compute and check the answer The answer is: 42 (my thanks to Wikipedia) After the 1960s, European and North American intellectuals tended to shift away from thinking basic questions about the meaning of life, a project which came to be considered – especially by academics – too laden with pathos; too – how shall I say it? – emotional. Everyone pays lip service nowadays to the so-called importance of going beyond the mind- body dualism of René Descartes and the Western Mindset, but our academic culture is still very intellect-centered, excluding the emotions, which are, of course, part of the body. -

The Anarchist Writings of Paul Goodman

Redrawing The Line: The Anarchist Writings of Paul Goodman Paul Comeau Spring, 2012 A review of Drawing The Line Once Again: Paul Goodman’s Anarchist Writings, PM Press, 2010, 122 pages, trade paperback, $14.95 While relatively unknown today, Paul Goodman was one of the most influential thinkers of the 20th century. In books like Growing Up Absurd, published in 1960, Goodman captured the zeitgeist of his era, catapulting himself to the forefront of American intellectual life as one of the leading dissident thinkers inspiring the burgeoning New Left. Goodman, who passed away in 1972 at the age of 60, was an iconoclastic radical with a wide ranging scope of intellectual vision and a multi-faceted character. He was an anarchist, a family man, openly bisexual in a sexually repressive era, a psychologist (one of the founders of Gestalt Therapy), and a poet. He saw himself as a classical man of letters, and at his peak output, released nearly a book ayear. PM Press has recently reprinted some of Goodman’s writings in three volumes. The first, Drawing The Line Once Again: Paul Goodman’s Anarchist Writings, col- lects short essays from throughout Goodman’s lifetime including “The May Pam- phlet,” one of his earliest pieces. Many of these pieces were later incorporated into his longer works. “The May Pamphlet” is in many ways Goodman’s manifesto, outlining someof his basic principles. From advocating a free society, to discussing the nature of language, to an examination of the education system and its function as a system of coercion, the themes and principles outlined in it are revisited time and again throughout his writings. -

Anarchy No. 33

—— Contents of No. 33 November 1963 ANARCHY 33 (Vol 3 No II) November 1 963 329 The Anarchism of Alex Comfort /<?/*« Ellerby 329 Sex, Kicks and Comfort Charles Radcliffe 340 Alex Comfort's Art and Scope Harold Drasdo 345 A Comfort Bibliography 357 A Disappointed Revolutionary Sid Parker 359 Cover by Rufus Segar Drawing on p. 329 by Frank Benier <0o Poem "Maturity" by Alex Comfort from Haste to the Wedding (Eyre and Spottiswoode 1962) The ANARCHISM of Other issues of ANARCHY 27. Talking about youth. 28. The future of anarchism. COMFORT 1. Sex-and-Violence; Galbraith; ALEX (out of print) 29. The Spies for Peace Story the New Wave, Education, 30. The community workshop. 31. Self-organising systems; 2. Workers' Control. beatniks; the state; practicability. 3. What does anarchism mean today?; 32. Crime. Africa; the Long Revolution; 4. De-institutionalisation; Conflicting Universities strains in anarchism. and Colleges ANARCHY can be obtained in term- 5. 1936: the Spanish Revolution. time from: (out of print) Oxford: Felix de Mendelssohn, J us i ai 1 1 r rut- WAR; two young writers on either side of the Atlantic 6. Anarchy and the Cinema. Oriel College. published collections of their wartime essays. Their books had a (out of print) Cambridge: Nicholas Bohm similar character, were of social as well as literary 7. Adventure Playgrounds. tone and both St. John's College. criticism, they even similar titles: Paul Goodman's was called (out of print) Birmingham: Anarchist Group. and had 8. Anarchists and Fabians; Action Sussex: Paul Littlewood, Art and Social Nature, Alex Comfort's was called Art and Social Anthropology; Eroding Capitalism; Students' Union. -

Marcus Cézar De Borba Belmino ONTOLOGIA GESTÁLTICA

Marcus Cézar de Borba Belmino ONTOLOGIA GESTÁLTICA: UM ENSAIO SOBRE A TEORIA DA EXPERIÊNCIA EM PAUL GOODMAN Tese submetida ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Filosofia da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, na área de Ontologia, para a obtenção do Grau de Doutor em Filosofia. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Marcos José Müller Florianópolis/SC 2016 Ficha de identificação da obra elaborada pelo autor, através do Programa de Geração Automática da Biblioteca Universitária da UFSC. Belmino, Marcus Cézar de Borba Ontologia Gestáltica: : Um ensaio sobre a teoria da experiência em Paul Goodman / Marcus Cézar de Borba Belmino ; orientador, Marcos José Müller - Florianópolis, SC, 2016. 367 p. Tese (doutorado) - Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Centro de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Filosofia. Inclui referências 1. Filosofia. 2. Gestalt-terapia. 3. Ontologia. 4. Fenomenologia. 5. Anarquia. I. , Marcos José Müller. II. Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina. Programa de Pós Graduação em Filosofia. III. Título. Para Tássia, Alice e Gabriel com todo o meu amor AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço primeiramente à minha família, que possibilitou que esse sonho pudesse se concretizar. Principalmente à Tássia Lobato Pinheiro Belmino, minha esposa que tanto me apoiou de todas as formas possíveis para que eu pudesse concluir essa empreitada. Foi seu empenho desde o amor e o companheirismo até ao debate de ideias e críticas às minhas formulações que possibilitaram o nascimento dessa tese. Agradeço aos meus filhos, Alice e Gabriel, que mesmo tão pequenos, sempre foram muito compreensíveis com as minhas longas viagens e também em relação a minha necessidade de sentar, estudar e escrever. Agradeço aos meus pais, Sebastião Belmino e Virginia Glaucia que sempre me apoiaram em todas as minhas escolhas que tive até aqui, sempre me dando amor e confiança, sem nunca duvidar de que essa e tantas outras vitórias fossem possíveis. -

Paul Goodman E O Problema Da Natureza Humana a Partir De Uma Leitura “Gestáltica”: Desdobramentos Para O Campo Da Política E Da Educação Anarquista

234 BELMINO, Marcus Cézar de Borba – Paul Goodman e o problema da natureza humana a partir de uma leitura “gestáltica”: desdobramentos para o campo da política e da educação anarquista. ARTIGO Paul Goodman e o problema da natureza humana a partir de uma leitura “gestáltica”: desdobramentos para o campo da política e da educação anarquista Paul Goodman and the problem of human nature from a Gestalt reading: consequences for the field of politics and anarchist education Marcus Cézar de Borba Belmino Revista IGT na Rede, v. 13, nº 25, 2016. p. 234 – 252. Disponível em http://www.igt.psc.br/ojs ISSN: 1807-2526 235 BELMINO, Marcus Cézar de Borba – Paul Goodman e o problema da natureza humana a partir de uma leitura “gestáltica”: desdobramentos para o campo da política e da educação anarquista. RESUMO Paul Goodman foi um anarquista, crítico literário, psicoterapeuta, membro do grupo inicial de criação da Gestalt-terapia e coautor do livro “Gestalt Therapy” e, também, um dos pilares do movimento de desescolarização. Este artigo aborda as discussões sobre a teoria da natureza humana e a antropologia de Paul Goodman, assim como seus desdobramentos para o campo da política e da educação. Para Goodman, a natureza humana foi perdida devido a um sistema social repressor que impede o desenvolvimento da criatividade, da sexualidade e das experiências interpessoais de vivência comunitária. Por isso, como forma de resgatar estes princípios básicos da natureza humana, Goodman aponta um sistema anarquista, descentralista e pacifista de organização política e uma nova proposta de educação pautada na desinstitucionalização dos jovens. Para tanto, procuramos desenvolver um estudo bibliográfico tendo como foco as obras de Paul Goodman, principalmente aquelas que tratam de seus fundamentos políticos, buscando compreender como Goodman entende a problemática da natureza humana e o campo das relações políticas. -

Escaping Education: Living As Learning Within Grassroots Cultures Madhu Suri Prakash and Gustavo Esteva

Escaping Education: Living as learning within grassroots cultures Madhu Suri Prakash and Gustavo Esteva. Table of Contents Prologue I. Education as a Human Right: The Trojan Horse of Recolonization The Different Faces arid Facets of Education Freedom and Mobility for the Individual Professional Careers for Growth, Security and Satisfaction Cultural Survival, Enrichment, and Diversity Reform, Revamping, Radicalization The Crassly Competitive Slayers of Savage Inequalities Cultural Literacy Promoters Multicultural Literacies Multicultural Education: An Oxymoron Human Rights: The Contemporary Trojan Horse The Nexus of Contemporary Domination: Education-Human Rights-Development Apologies and Celebration Hosting the Otherness of the Other II. Grassroots Postmodernism: Refusenik Cultures The First Intercultural Dialogue? Educating the Indians The First Multicultural Educator of the Americas The Failure of Education Escaping Education: Learning to Listen, then Listening From Resistance to Liberation Table of Contents The Diversity of Liberation in the Lived Pluriverse Dropping Out Waking Up: Diplomas in the Survival Kit? Emerging Coalitions of Discontents The Return of the Incarnated Intellectual But What to Do with the Children? Dissolving Needs Grassroots Postmodernism II After Education, What? Developing Education Time of Renewal The Failure of Deschooling Beyond Deschooling: Education Stood on Its Head Inverting Pandora’s Box Living Without Schools or Education Margins and Centers: Escaping the /m Mythopoesis of Education Incarnated Intellectuals Contemporary Prophets 3 Epilogue Rooting, Rerooting Ruralization Reclaiming the Commons David and Goliath I am ashamed to think how easily we capitulate to badges and names, to large societies and dead institutions ... I ought to go upright and vital, and speak the rude truth in all ways. If malice and vanity wear the coat of philanthropy, shall that pass? Ralph Waldo Emerson, Self-Reliance Prologue O my soul, do not aspire to immortal life, but exhaust the limits of the possible.