MAP Technical Reports Series No. 93

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thank You for Purchasing This Tesla Immersion Heater. This Unit Is

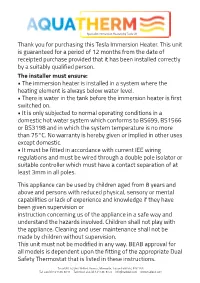

Specialist Immersion Heaters by Tesla UK Thank you for purchasing this Tesla Immersion Heater. This unit is guaranteed for a period of 12 months from the date of receipted purchase provided that it has been installed correctly by a suitably qualified person. The installer must ensure: • The immersion heater is installed in a system where the heating element is always below water level. • There is water in the tank before the immersion heater is first switched on. • It is only subjected to normal operating conditions in a domestic hot water system which conforms to BS699, BS1566 or BS3198 and in which the system temperature is no more than 75°C. No warranty is hereby given or implied in other uses except domestic. • It must be fitted in accordance with current IEE wiring regulations and must be wired through a double pole isolator or suitable controller which must have a contact separation of at least 3mm in all poles. This appliance can be used by children aged from 8 years and above and persons with reduced physical, sensory or mental capabilities or lack of experience and knowledge if they have been given supervision or instruction concerning us of the appliance in a safe way and understand the hazards involved. Children shall not play with the appliance. Cleaning and user maintenance shall not be made by children without supervision. This unit must not be modified in any way. BEAB approval for all models is dependent upon the fitting of the appropriate Dual Safety Thermostat that is listed in these instructions. Tesla UK Ltd, Unit 3b First Avenue, Minworth, Sutton Coldfield, B76 1BA Tel: +44 (0) 121 686 8711 Technical: +44 (0) 121 686 8733 [email protected] www.teslauk.com Specialist Immersion Heaters by Tesla UK General Fitting Information The Aquatherm range of immersion heaters are direct equivalents to the immersion heaters fitted to Heatrae Sadia Megaflo cylinders. -

Immersion Into Noise

Immersion Into Noise Critical Climate Change Series Editors: Tom Cohen and Claire Colebrook The era of climate change involves the mutation of systems beyond 20th century anthropomorphic models and has stood, until recent- ly, outside representation or address. Understood in a broad and critical sense, climate change concerns material agencies that im- pact on biomass and energy, erased borders and microbial inven- tion, geological and nanographic time, and extinction events. The possibility of extinction has always been a latent figure in textual production and archives; but the current sense of depletion, decay, mutation and exhaustion calls for new modes of address, new styles of publishing and authoring, and new formats and speeds of distri- bution. As the pressures and re-alignments of this re-arrangement occur, so must the critical languages and conceptual templates, po- litical premises and definitions of ‘life.’ There is a particular need to publish in timely fashion experimental monographs that redefine the boundaries of disciplinary fields, rhetorical invasions, the in- terface of conceptual and scientific languages, and geomorphic and geopolitical interventions. Critical Climate Change is oriented, in this general manner, toward the epistemo-political mutations that correspond to the temporalities of terrestrial mutation. Immersion Into Noise Joseph Nechvatal OPEN HUMANITIES PRESS An imprint of MPublishing – University of Michigan Library, Ann Arbor, 2011 First edition published by Open Humanities Press 2011 Freely available online at http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.9618970.0001.001 Copyright © 2011 Joseph Nechvatal This is an open access book, licensed under the Creative Commons By Attribution Share Alike license. Under this license, authors allow anyone to download, reuse, reprint, modify, distribute, and/or copy this book so long as the authors and source are cited and resulting derivative works are licensed under the same or similar license. -

Michael Jackson's Gesamtkunstwerk

Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies Vol. 11, No. 5 (November 2015) Michael Jackson’s Gesamtkunstwerk: Artistic Interrelation, Immersion, and Interactivity From the Studio to the Stadium Sylvia J. Martin Michael Jackson produced art in its most total sense. Throughout his forty-year career Jackson merged art forms, melded genres and styles, and promoted an ethos of unity in his work. Jackson’s mastery of combined song and dance is generally acknowledged as the hallmark of his performance. Scholars have not- ed Jackson’s place in the lengthy soul tradition of enmeshed movement and mu- sic (Mercer 39; Neal 2012) with musicologist Jacqueline Warwick describing Jackson as “embodied musicality” (Warwick 249). Jackson’s colleagues have also attested that even when off-stage and off-camera, singing and dancing were frequently inseparable for Jackson. James Ingram, co-songwriter of the Thriller album hit “PYT,” was astonished when he observed Jackson burst into dance moves while recording that song, since in Ingram’s studio experience singers typically conserve their breath for recording (Smiley). Similarly, Bruce Swedien, Jackson’s longtime studio recording engineer, told National Public Radio, “Re- cording [with Jackson] was never a static event. We used to record with the lights out in the studio, and I had him on my drum platform. Michael would dance on that as he did the vocals” (Swedien ix-x). Surveying his life-long body of work, Jackson’s creative capacities, in fact, encompassed acting, directing, producing, staging, and design as well as lyri- cism, music composition, dance, and choreography—and many of these across genres (Brackett 2012). -

26.04.2016 Press Release Pop-Kultur

Press Release April 26, 2016, Berlin – Preview 2016: SELDA BAĞCAN feat. BOOM PAM / KEØMA / LIARS / FATIMA AL QADIRI / ROOSEVELT / BRANDT BRAUER FRICK / TRÜMMER / RICHARD HELL / ALGIERS / MATTHEW HERBERT / IMMERSION / SASSY BLACK / YOUR FRIEND / CAT’S EYES / FRANKIE COSMOS / A-WA / ZOLA JESUS / LUH / ZEBRA KATZ / DIÄT / IMARHAN – The complete lineup will be revealed at the presale start on May 9th, 2016 – Today on www.pop-kultur.berlin: Film premiere »Kurt’s Lighter« by Paul Kelly »Pop-Kutur« releases first names and highlights of its 2016 edition and announces that ticket presale starts on May 9th. “We consequently developed our concept for Pop-Kultur and asked ourselves: What trends and issues are currently relevant in the different pop-cultural scenes. We want to display today’s topics in real time – through concerts, talks, and workshops – without repeating ourselves.”, says Christian Morin, once more responsible for the lineup, together with Katja Lucker and Martin Hossbach. While »Pop- Kultur« 2015 was located in the Berghain, this year’s edition – August 31st – September 2nd – will spread throughout Neukölln, from the legendary SchwuZ, serving as the festivalcenter. The other venues, reachable by foot, are Heimathafen Neukölln, Huxleys Neue Welt, Passage-Kino, Keller, Prachtwerk. Selda Ba One of this year’s headliners is Selda Bağcan. For a lot of people, the dignified artist is not only one of the great voices of Anatolian psych Rock ğ music, she is the greatest voice. It’s crystal can clarity immediately engraves into your Soul. »Pop- Kultur« brings the opinion leader and favorite singer of Anohni (Antony Hegarty) and Elija Wood, amongst others, together with the band Boom Pam, back to Berlin. -

Hot Air Solder Levelling in the Lead-Free

Hot Air Solder Leveling in the Lead-free Era Keith Sweatman Nihon Superior Co., Ltd. Osaka, Japan Abstract Although the advantages of Hot Air Solder Leveling (HASL) in providing the most robust solderable finish for printed circuit boards are well recognized, in the years leading up to the implementation of the EU RoHS Directive in July 2006 the conventional wisdom was that it would have no place in the new lead-free electronics manufacturing technology. The widely promoted view was that HASL, which had been the most popular printed circuit board finish in North America, Europe and most of Asia outside Japan during the tin-lead era, would be largely replaced in the lead-free era by Organic Solderability Protectants (OSP) and immersion silver with perhaps a minor role for immersion tin. This view was reinforced by some early trials of lead-free HASL in which the tin-silver-copper alloy, then promoted as the universal lead-free replacement for tin-lead, was used as the coating alloy. The aggressive dissolution of copper by that alloy and its non-eutectic behavior made it difficult to use and to get satisfactory results. In the meantime, however, in Europe a microalloyed tin-copper alloy with low copper dissolution and eutectic behavior was evaluated and found to yield promising results. A smooth mirror-bright finish could be achieved on existing equipment with process temperatures that existing laminate materials could accommodate. An unexpected advantage was that the thickness of the lead-free HASL finish was more uniform than typically obtained with tin-lead so that it could be used in applications previously excluded to tin-lead HASL because of concerns about coplanarity, e.g. -

SERIOUS Interconnect Cable CAPABILITIES

QwikConnect GLENAIR • JULY 2017 • VOLUME 21 NUMBER 3 SERIOUS Interconnect Cable CAPABILITIES Mario Trevino, Glenair Complex Cable Group QwikConnect ilitary, aerospace, and harsh-environment industrial interconnect applications require MEWIS cabling of a caliber not generally found on consumer-grade applications such SERIOUS as desktop computers or automobiles. In fact, the typical interconnect cable assembly made for high performance applications — from fighter jets to dismounted soldier systems — has little in Interconnect Cable common with their more pedestrian cousins in the consumer product arena including better shielding from electromagnetic interference, higher levels of environmental sealing and superior all-around CAPABILITIES mechanical performance. Lightweight Mighty Mouse 806 Lightweight, flexible, High-temperature tolerant SWAMP zone sensor/ abrasion-resistant power Miniaturized space-grade reusable wire-protection transducer and data cables for soldier harness assemblies conduit assembly interconnect C4ISR hubs for space launch cable applications assemblies Multibranch overbraided Nomex® High-speed fiber optic in-flight entertainment cable assemblies with cable jumpers overmolded connector High-density power junctions connector cables for extreme environments 2 QwikConnect • July 2017 Glenair: Where Connector Manufacturing and manufacturing capabilities combined with our Meets Cable Harness Assembly many years of experience in military grade and harsh environmental commercial cable harness fabrication. If there is one thing -

Canadian English: a Linguistic Reader

Occasional Papers Number 6 Strathy Language Unit Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario Canadian English: A Linguistic Reader Edited by Elaine Gold and Janice McAlpine Occasional Papers Number 6 Strathy Language Unit Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario Canadian English: A Linguistic Reader Edited by Elaine Gold and Janice McAlpine © 2010 Individual authors and artists retain copyright. Strathy Language Unit F406 Mackintosh-Corry Hall Queen’s University Kingston ON Canada K7L 3N6 Acknowledgments to Jack Chambers, who spearheaded the sociolinguistic study of Canadian English, and to Margery Fee, who ranges intrepidly across the literary/linguistic divide in Canadian Studies. This book had its beginnings in the course readers that Elaine Gold compiled while teaching Canadian English at the University of Toronto and Queen’s University from 1999 to 2006. Some texts gathered in this collection have been previously published. These are included here with the permission of the authors; original publication information appears in a footnote on the first page of each such article or excerpt. Credit for sketched illustrations: Connie Morris Photo credits: See details at each image Contents Foreword v A Note on Printing and Sharing This Book v Part One: Overview and General Characteristics of Canadian English English in Canada, J.K. Chambers 1 The Name Canada: An Etymological Enigma, 38 Mark M. Orkin Canadian English (1857), 44 Rev. A. Constable Geikie Canadian English: A Preface to the Dictionary 55 of Canadian English (1967), Walter S. Avis The -

Fish TLR4 Does Evolution of Lipopolysa

Evolution of Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) Recognition and Signaling: Fish TLR4 Does Not Recognize LPS and Negatively Regulates NF- κB Activation This information is current as of September 27, 2021. María P. Sepulcre, Francisca Alcaraz-Pérez, Azucena López-Muñoz, Francisco J. Roca, José Meseguer, María L. Cayuela and Victoriano Mulero J Immunol 2009; 182:1836-1845; ; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801755 Downloaded from http://www.jimmunol.org/content/182/4/1836 References This article cites 50 articles, 13 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/ http://www.jimmunol.org/content/182/4/1836.full#ref-list-1 Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists by guest on September 27, 2021 • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2009 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. The Journal of Immunology Evolution of Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) Recognition and Signaling: Fish TLR4 Does Not Recognize LPS and Negatively Regulates NF-B Activation1 María P. Sepulcre,* Francisca Alcaraz-Pe´rez,2*† Azucena Lo´pez-Mun˜oz,2* Francisco J. -

The Two-Way Immersion Toolkit

The Two-Way Immersion Toolkit Elizabeth Howard, Julie Sugarman, Marleny Perdomo, and Carolyn Temple Adger ������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������������ Since 1975, The Education Alliance, a department at Brown University, has helped the education community improve schooling for our children. We conduct applied research and evaluation, and provide technical assistance and informational resources to connect research and practice, build knowledge and skills, and meet critical needs in the fi eld. With offi ces in Rhode Island, New York, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands, and a dedicated team of over 100 skilled professionals, we provide services and resources to K-16 institutions across the country and beyond. As we work with educators, we customize our programs to the specifi c needs of our clients. Northeast and Islands Regional Educational Laboratory (LAB) The Education Alliance at Brown University is home to the Northeast and Islands Regional Educational Laboratory (LAB), one of ten educational laboratories funded by the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences. Our goals are to improve teaching and learning, advance school improvement, build capacity for reform, and develop strategic alliances with key members of the region’s education and policymaking community. The LAB develops educational products and services for school administrators, policymakers, teachers, and parents in New England, New York, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. -

Electric Immersion Heaters

electric immersion heaters electric heating and controls Table Of Contents Selection Guide . 1-3. Quick Ship Screw Plug Heaters . 4-8. Construction Features . 4 1” Screw Plug Heaters . 5 1-1/4” Screw Plug Heaters . 6 2” Screw Plug Heaters . 7 2-1/2” Screw Plug Heaters . 8 Stock Screw Plug Heater . 9 Screw Plug Heaters . 10-17. 1” Screw Plug Heaters . 10 1-1/4” Screw Plug Heaters . 11-12. 2” Screw Plug Heaters . 13-15. 2-1/2” Screw Plug Heaters . 16-17. Heater Options . 17 Flange Heaters . 18-28. Construction Features . 18-21. Water Heaters . 22-24. Oil Heaters . 25-26. Heater Options . 27-28. Over-the-Side Heaters . 29-31. Construction Features . 29 Heater Options . 29 Water Heaters . 30 Oil Heaters . 31 CSA Listed Explosion-proof Heaters . 32-35. Construction Features . 32 Temperature Code Calculations . 33 Water Heaters . 34 Oil Heaters . 35 Tank and Basin Heaters . 36-38. Pipe Insert Heaters . 36 Deep Tank Heaters . 36 Cooling Tower Heaters . 37-38. Control Panels . 39-41. Contactor Control Panels . 39 SCR Control Panels . 40 Cooling Tower Control Panels . 41 Thermostats and Accessories . 42-44. Special Purpose Heaters . 45-46. Bottom-Mounted Heaters . 45 Rectangular Flange Heaters . 46 Series 770 Flange Heaters . 46 Dimension Sheet for Screw Plug Heaters . 47-48. Limited Warranty . Back Cover Selection Guide Selection Guide Heater construction is selected on the basis of the following criteria: Calculating KW Capacity • Space Available for both elements and headers. If a great In general, KW capacity will be determined by one of two fac- deal of heat must be concentrated in a small volume, one tors: the heat required to bring the process up to temperature, heater with multiple elements should be used. -

NOCTURNAL EMISSIONS a Diary of Dreams

NOCTURNAL EMISSIONS a diary of dreams nathan j robinson may all your nightmares disappear and all your dreams be realized. “And what if there are only spiders there, or some- thing of that sort? … We always imagine eternity as something beyond our conception, something vast, vast! But why must it be vast? Instead of all that, what if it’s one little room, like a bath house in the country, black and grimy and spiders in every corner, and that’s all eternity is? I sometimes fancy it like that.” —Dostoevsky TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction........................................................13 A Concentration in Triangles..................................19 Zatz............................................................................... 19 Te Bill Gates Scholarship....................................... 21 Roger............................................................................ 23 Te Package................................................................ 26 Te Perfect Smile....................................................... 29 Te Girl Who Wrote For BuzzFeed....................... 31 Nosebleed.................................................................... 33 Te Pornographers’ Convention............................ 36 A Beard........................................................................ 36 Manatee County Jail................................................. 37 Four Flashes................................................................ 37 Te Golan Heights................................................... 39 -

School Catalog

School Catalog Rev. 1/5/15-1/4/16 Millennium Academy of Hair, LLC 4009 MAIN STREET BRIDGEPORT, CT 06606 (203)549-9911 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents Page 2 Introduction/Objective Page 3 State of Connecticut: Laws & Regulations Pages 4-14 Guidelines for Prevention of HIV & Hepatitis B Pages 15-17 Sanitation Procedure Page 18 Cosmetology Kit List Pages 19 Rules and Regulations Page 20 Admissions Policy and Barriers to Employment Page 21 Absence/ Tardiness Policy Page 21 Makeup Policy Page 21 Policy Changes Page 21 Termintation Policy Page 21 Drug Free Statement Page 22 Program Outline Pages 23-25 Grading Scale Page 26 Graduation Requirements Page 26 Satisfactory Progress Policy: Evaluation Periods, Reporting Forms & Pages 27-28 Sample Forms Appeal Page 28 Leave of Absence Page 28 Withdrawal & and Program Incomplete Page 28 Sample Termination Letter Page 29 Internal Complaint Procedure Page 30 Information Security Plan/Notice of Non-disclosure of Information Pages 30-32 FERPA Page 33 Student Records Policy Page 34 School Advisors Page 34 Resource Center Page 34 Off Premise Activity Waiver & Release Page 35 Photo Release Page 36 Guidelines for Success / Goal Setting Pages 37-38 Acknowledgment Page 39 Tuition, Fees, Costs and Payment information Page 40 Refund Policy Pages 41-42 Barbering Program Outline and Barbering Kit Pages 43-45 List of School Staff and Title Page(s) 46 Facility Pages 46 Placement Information Page 46 School Schedule Page(s) 46 Room and Board Page 46 Page | 2 INTRODUCTION/OBJECTIVE Message From The School President: Welcome to Millennium Academy of Hair, LLC.