What If There's No Brexit Deal?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

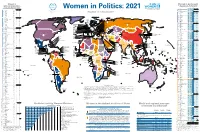

Women in Ministerial Positions, Reflecting Appointments up to 1 January 2021

Women in Women in parliament The countries are ranked and colour-coded according to the percentage of women in unicameral parliaments or the lower house of parliament, ministerial positions reflecting elections/appointments up to 1 January 2021. The countries are ranked according to the percentage of women in ministerial positions, reflecting appointments up to 1 January 2021. Rank Country Lower or single house Upper house or Senate % Women Women/Seats % Women Women/Seats Rank Country % Women Women Total ministers ‡ Women in Politics: 2021 50 to 65% 50 to 59.9% 1 Rwanda 61.3 49 / 80 38.5 10 / 26 1 Nicaragua 58.8 10 17 2 Cuba 53.4 313 / 586 — — / — 2 Austria 57.1 8 14 3 United Arab Emirates 50.0 20 / 40 — — / — ” Belgium 57.1 8 14 40 to 49.9% ” Sweden 57.1 12 21 4 Nicaragua 48.4 44 / 91 — — / — 5 Albania 56.3 9 16 Situation on 1 January 2021 5 New Zealand 48.3 58 / 120 — — / — 6 Rwanda 54.8 17 31 6 Mexico 48.2 241 / 500 49.2 63 / 128 7 Costa Rica 52.0 13 25 7 Sweden 47.0 164 / 349 — — / — 8 Canada 51.4 18 35 8 Grenada 46.7 7 / 15 15.4 2 / 13 9 Andorra 50.0 6 12 9 Andorra 46.4 13 / 28 — — / — ” Finland 50.0 9 18 10 Bolivia (Plurinational State of) 46.2 60 / 130 55.6 20 / 36 ” France 50.0 9 18 11 Finland 46.0 92 / 200 — — / — ” Guinea-Bissau* 50.0 8 16 12 South Africa 45.8 182 / 397 41.5 22 / 53 ” Spain 50.0 11 22 13 Costa Rica 45.6 26 / 57 — — / — 40 to 49.9% 14 Norway 44.4 75 / 169 — — / — 14 South Africa 48.3 14 29 15 Namibia 44.2 46 / 104 14.3 6 / 42 15 Netherlands 47.1 8 17 Greenland Latvia 16 Spain 44.0 154 / 350 40.8 108 / 265 16 -

CARIFORUM-UE 3651/18 1 the Fourth Meeting of the Joint

CARIFORUM-EU Brussels, 6 November 2018 ECONOMIC PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENT CARIFORUM-UE 3651/18 MINUTES Subject: Minutes of the Fourth Meeting of the Joint CARIFORUM-EU Council, held on 17 November 2017 in Brussels, Belgium The Fourth Meeting of the Joint CARIFORUM-EU Council (referred to hereafter as 'the Joint Council') took place in Brussels, Belgium, on 17 November 2017. The Joint Council was chaired on behalf of the European Union jointly by Mr Sven MIKSER, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Estonia, who represented the Council of the EU, and by Ms Cecilia MALMSTRÖM, European Commissioner for Trade. Ms Kamina JOHNSON SMITH, Minister of Foreign Affairs and Foreign Trade of Jamaica, served as CARIFORUM High Representative. CARIFORUM-UE 3651/18 1 EN 1. OPENING OF THE MEETING The Co-Chairs welcomed the participants to the Meeting. The list of participants is set out in Annex 1 to these Minutes. 2. ADOPTION OF AGENDA The Joint Council adopted the agenda as set out in document CARIFORUM-UE 3651/1/17 REV 1, as set out in Annex 2 to these Minutes. 3. PROCEDURAL MATTERS The Joint Council agreed on the procedures for conducting its business. 4. IMPLEMENTATION PROGRESS REPORT BY THE CARIFORUM-EU TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE The Joint Council took note of the oral progress report by the EU on the Seventh Meeting of the CARIFORUM-EU Trade and Development Committee (TDC), held on 15 November 2017 in Brussels, Belgium. The progress report is set out in Annex 3A to these Minutes. The essence of the reaction by the CARIFORUM High Representative is set out in Annex 3B to these Minutes. -

A Changing of the Guards Or a Change of Systems?

BTI 2020 A Changing of the Guards or A Change of Systems? Regional Report Sub-Saharan Africa Nic Cheeseman BTI 2020 | A Changing of the Guards or A Change of Systems? Regional Report Sub-Saharan Africa By Nic Cheeseman Overview of transition processes in Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe This regional report was produced in October 2019. It analyzes the results of the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) 2020 in the review period from 1 February 2017 to 31 January 2019. Author Nic Cheeseman Professor of Democracy and International Development University of Birmingham Responsible Robert Schwarz Senior Project Manager Program Shaping Sustainable Economies Bertelsmann Stiftung Phone 05241 81-81402 [email protected] www.bti-project.org | www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/en Please quote as follows: Nic Cheeseman, A Changing of the Guards or A Change of Systems? — BTI Regional Report Sub-Saharan Africa, Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung 2020. https://dx.doi.org/10.11586/2020048 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). Cover: © Freepick.com / https://www.freepik.com/free-vector/close-up-of-magnifying-glass-on- map_2518218.htm A Changing of the Guards or A Change of Systems? — BTI 2020 Report Sub-Saharan Africa | Page 3 Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................... -

FOREIGN AFFAIRS COUNCIL Brussels, 16 July 2018

FOREIGN AFFAIRS COUNCIL Brussels, 16 July 2018 PARTICIPANTS High Representative Ms Federica MOGHERINI High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Belgium: Mr Didier REYNDERS Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Foreign and European Affairs, with responsibility for Beliris and Federal Cultural Institutions Bulgaria: Ms Emilia KRALEVA Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs Czech Republic: Mr Jan HAMÁČEK Vice Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs Denmark: Mr Anders SAMUELSEN Minister for Foreign Affairs Germany: Mr Michael ROTH Minister of State, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Estonia: Mr Sven MIKSER Minister for Foreign Affairs Ireland: Mr Declan KELLEHER Permanent Representative Greece: Mr Georgios KATROUGALOS Deputy Minister for European Affairs Spain: Mr Josep BORRELL FONTELLES Minister for Foreign Affairs and Cooperation France: Mr Jean-Yves LE DRIAN Minister for Europe and for Foreign Affairs Croatia: Ms Marija PEJČINOVIĆ BURIĆ Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Foreign and European Affairs Italy: Ms Emanuela Claudia DEL RE State Secretary for Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation Cyprus: Mr Nikos CHRISTODOULIDES Minister for Foreign Affairs Latvia: Mr Edgars RINKĒVIČS Minister for Foreign Affairs Lithuania: Mr Linas LINKEVIČIUS Minister of Foreign Affairs Luxembourg: Mr Jean ASSELBORN Minister for Foreign and European Affairs, Minister for Immigration and Asylum Hungary: Mr Péter SZIJJÁRTÓ Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade Malta: Mr Carmelo ABELA Minister for Foreign Affairs and and -

Quick Guide More Information on the European Defence Agency Is Available at

www.eda.europa.eu Quick guide More information on the European Defence Agency is available at : www.eda.europa.eu European Defence Agency - Quick guide ISBN : 978-92-95075-31-3 DOI : 10.2836/07889 © European Defence Agency, 2016 For reproduction or use of this material, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holder. For any use or reproduction of individual photos, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. Photo credits : p. 12 ©EEAS, P. 13 ©The European Union, p. 14 ©Luftwaffe, p. 15 ©Airbus Group, p. 17 ©Thales Alenia Space, p. 18 © eda, p. 19 © eda, p. 20 ©Austrian Ministry of Defence, p. 21 ©Eurocontrol, p. 22 ©European Commission Archives, p. 23 ©European Commission Archives Responsible editor : Eric Platteau PRINTED IN BELGIUM PRINTED ON ELEMENTAL CHLORINE-FREE BLEACHED PAPER (ECF) 2 EUROPEAN DEFENCE AGENCY Quick guide BRUSSELS » 2016 3 CONTENT 1 | WHO WE ARE 06 Our structure 06 Our missions 07 Our organisation 08 The EDA’s added value 09 2 | HOW WE WORK 10 Close cooperation with other EU structures 11 Close cooperation with non-EU actors and third parties 11 Pooling & Sharing 12 3 | WHAT WE DO 13 EDA’s four main capability development programmes 14 Air-to-Air Refuelling (AAR) 14 Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems 15 Cyber Defence 16 Governmental Satellite Communications (GovSatCom) 16 Examples of efficient cooperation enabled by EDA 17 Airlift Trainings & Exercises 17 Counter-Improvised Explosive Devices 18 Military Airworthiness 18 Support to Operations 19 Examples of EDA acting as an interface -

Brexit: the Unintended Consequences

A SYMPOSIUM OF VIEWS Brexit: The Unintended Consequences Bold policy changes always seem to produce unintended consequences, both favorable and unfavorable. TIE asked more than thirty noted experts to share their analysis of the potential unintended consequences—financial, economic, political, or social—of a British exit from the European Union. 6 THE INTERNATIONAL ECONOMY SPRING 2016 Britain has been an liberal approaches to various elements of financial market frameworks. essential part of an Yet our opinions can differ. First, we have almost completely different experiences with our countries’ fi- opinion group nancial industries during the Great Recession. The Czech financial sector served as a robust buffer, shielding us defending more from some of the worst shocks. The British have had a rather different experience with their main banks, which market-based and to some extent drives their position on risks in retail bank- ing. This difference is heightened by the difference in the liberal approaches. relative weight of financial institutions in our economies, as expressed by the size of the financial sector in relation MIROSLav SINGER to GDP. The fact that this measure is three to four times Governor, Czech National Bank larger in the United Kingdom than in the Czech Republic gives rise to different attitudes toward the risk of crisis in here is an ongoing debate about the economic mer- the financial industry and to possible crisis resolution. In its and demerits of Brexit in the United Kingdom. a nutshell, in sharp contrast to the United Kingdom, the THowever, from my point of view as a central banker Czech Republic can—if worse comes to worst—afford to from a mid-sized and very open Central European econ- close one of its major banks, guarantee its liabilities, and omy, the strictly economic arguments are in some sense take it into state hands to be recapitalized and later sold, overwhelmed by my own, often very personal experience without ruining its sovereign rating. -

Ten Issues to Watch in 2021

ISSN 2600-268X Ten issues to watch in 2021 IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service Author: Étienne Bassot Members' Research Service PE 659.436 – January 2021 EN This EPRS publication seeks to offer insights and put into context ten key issues and policy areas that are likely to feature prominently on the political agenda of the European Union in 2021. It has been compiled and edited by Isabelle Gaudeul-Ehrhart of the Members' Research Service, based on contributions from the following policy analysts: Marie-Laure Augère and Anna Caprile (Food for all? Food for thought), Denise Chircop and Magdalena Pasikowska-Schnass (Culture in crisis?), Costica Dumbrava (A new procedure to manage Europe's borders), Gregor Erbach (A digital boost for the circular economy), Silvia Kotanidis (Conference on the Future of Europe, in the introduction), Elena Lazarou (A new US President in the White House), Marianna Pari (The EU recovery plan: Turning crisis into opportunity?), Jakub Przetacznik and Nicole Scholz (The vaccine race for health safety), Ros Shreeves and Martina Prpic (Re-invigorating the fight against inequality?), Branislav Staniček (Turkey and stormy waters in the eastern Mediterranean) and Marcin Szczepanski (Critical raw materials for Europe). The cover image was produced by Samy Chahri. Further details of the progress of on-going EU legislative proposals, including all those mentioned in this document, are available in the European Parliament's Legislative Train Schedule, at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/legislative-train/ LINGUISTIC VERSIONS Original: EN Translations: DE, FR Manuscript completed in January 2021. DISCLAIMER AND COPYRIGHT This document is prepared for, and addressed to, the Members and staff of the European Parliament as background material to assist them in their parliamentary work. -

Monthly Forecast

May 2021 Monthly Forecast 1 Overview Overview 2 In Hindsight: Is There a Single Right Formula for In May, China will have the presidency of the Secu- Da’esh/ISIL (UNITAD) is also anticipated. the Arria Format? rity Council. The Council will continue to meet Other Middle East issues include meetings on: 4 Status Update since our virtually, although members may consider holding • Syria, the monthly briefings on political and April Forecast a small number of in-person meetings later in the humanitarian issues and the use of chemical 5 Peacekeeping month depending on COVID-19 conditions. weapons; China has chosen to initiate three signature • Lebanon, on the implementation of resolution 7 Yemen events in May. Early in the month, it will hold 1559 (2004), which called for the disarma- 8 Bosnia and a high-level briefing on Upholding“ multilateral- ment of all militias and the extension of gov- Herzegovina ism and the United Nations-centred internation- ernment control over all Lebanese territory; 9 Syria al system”. Wang Yi, China’s state councillor and • Yemen, the monthly meeting on recent 11 Libya minister for foreign affairs, is expected to chair developments; and 12 Upholding the meeting. Volkan Bozkir, the president of the • The Middle East (including the Palestinian Multilateralism and General Assembly, is expected to brief. Question), also the monthly meeting. the UN-Centred A high-level open debate on “Addressing the During the month, the Council is planning to International System root causes of conflict while promoting post- vote on a draft resolution to renew the South Sudan 13 Iraq pandemic recovery in Africa” is planned. -

Planning for EU Military Operations

January 2010 81 Command and control? Planning for EU military operations Luis Simón ISBN 978-92-9198-161-8 ISSN 1608-5000 QN-AB-10-081-EN-C published by the European Union Institute for Security Studies 43 avenue du Président Wilson - 75775 Paris cedex 16 - France phone: + 33 (0) 1 56 89 19 30 fax: + 33 (0) 1 56 89 19 31 e-mail: [email protected] www.iss.europa.eu European union Institute for Security Studies OCCASIONAL PAPErS n° 80 Oct 2009 Risky business? The EU, China and dual-use technology May-Britt U. Stumbaum n° 79 Jun 2009 The interpolar world: a new scenario Giovanni Grevi n° 78 Apr 2009 Security Sector Reform in Afghanistan: the EU’s contribution The Institute for Security Studies (EUISS) Eva Gross n° 77 Mar 2009 From Suez to Shanghai: The European Union and Eurasian maritime security was created in January 2002 as a Paris-based autonomous agency of the European Union. James Rogers Following an EU Council Joint Action of 20 July 2001, modified by the Joint Action of 21 December 2006, it is now an integral part of the new structures that will support the fur- n° 76 Feb 2009 EU support to African security architecture: funding and training components ther development of the CFSP/ESDP. The Institute’s core mission is to provide analyses and Nicoletta Pirozzi recommendations that can be of use and relevance to the formulation of EU policies. In n° 75 Jan 2009 Les conflits soudanais à l’horizon 2011 : scénarios carrying out that mission, it also acts as an interface between experts and decision-makers Jean-Baptiste Bouzard at all levels. -

Norway: Defence 2008

Norwegian Defence 2008 Norwegian Defence 2008 2 CONTENT NORWEGIAN SECURITY And DEFEncE POLICY 4 1. Security Policy Objectives 5 Defence Policy Objectives 5 2. Defence Tasks 6 3. Areas of Government Focus 7 4. International Cooperation 8 UN 8 NATO 9 EU 10 Nordic cooperation 11 5. National Cooperation 12 DEFEncE STRUCTURE And AcTIVITIES 14 1. Constitutional Division of Responsibility in Norway 15 2. The Strategic Leadership of the Armed Forces 15 The Ministry Of Defence 16 3. The Defence Agencies 17 The Norwegian Armed Forces 17 4. The Norwegian Armed Forces 18 5. The Service Branches 19 The Norwegian Army 19 The Royal Norwegian Navy 20 Royal Norwegian Air Force 21 Home Guard 22 6. Personnel Policy 23 7. National Service 23 8. Materiel and Investments 24 Overview of Forces Engaged in International Operations 25 SUppLEMENt – THE FACTS 26 1. The Defence Budget 27 2. International Operations 27 3. Ranks and Insignia 28 4. Non-Governmental Organisations 29 5. Addresses 32 Norwegian Security and Defence Policy 4 1. SECURITY POLICY OBJECTIVES The principal objective of Norwegian security policy is to safeguard and promote national security policy interests. This is best achieved by contributing to peace, security and stability both in areas adjacent to Norway and in the wider world. Nationally Norway must be in a position to uphold its sovereignty and sove- reign rights and to exercise authority in order to safeguard our interests. At the same time, the progress of globalisation means that geo- graphical distance is no longer a determining factor for potential threats to our security. -

Economic Partnership Agreement Between the Cariforum States, of the One Part, and the European Community and Its Member States, of the Other Part

Organization of American States ECONOMIC PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE CARIFORUM STATES, OF THE ONE PART, AND THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY AND ITS MEMBER STATES, OF THE OTHER PART Article 1 The objectives of this Agreement are: a)Contributing to the reduction and eventual eradication of poverty through the establishment of a trade partnership consistent with the objective of sustainable development, the Millennium Development Goals and the Cotonou Agreement; b)Promoting regional integration, economic cooperation and good governance thus establishing and implementing an effective, predictable and transparent regulatory framework for trade and investment between the Parties and in the CARIFORUM region; c)Promoting the gradual integration of the CARIFORUM States into the world Objectives economy, in conformity with their political choices and development priorities; d)Improving the CARIFORUM States' capacity in trade policy and trade related issues; e)Supporting the conditions for increasing investment and private sector initiative and enhancing supply capacity, competitiveness and economic growth in the CARIFORUM region; f)Strengthening the existing relations between the Parties on the basis of solidarity and mutual interest. To this end, taking into account their respective levels of development and consistent with WTO obligations, the Agreement shall enhance commercial and economic relations, support a new trading dynamic between the Parties by means of the progressive, asymmetrical liberalisation of trade between them and reinforce, broaden -

Finnish Defence Forces International Centre the Many Faces of Military

Finnish Defence Forces International Finnish Defence Forces Centre 2 The Many Faces of Military Crisis Management Lessons from the Field Edited by Mikaeli Langinvainio Finnish Defence Forces FINCENT Publication Series International Centre 1:2011 1 FINNISH DEFENCE FORCES INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FINCENT PUBLICATION SERIES 1:2011 The Many Faces of Military Crisis Management Lessons from the Field EDITED BY MIKAELI LANGINVAINIO FINNISH DEFENCE FORCES INTERNATIONAL CENTRE TUUSULA 2011 2 Mikaeli Langinvainio (ed.): The Many Faces of Military Crisis Management Lessons from the Field Finnish Defence Forces International Centre FINCENT Publication Series 1:2011 Cover design: Harri Larinen Layout: Heidi Paananen/TKKK Copyright: Puolustusvoimat, Puolustusvoimien Kansainvälinen Keskus ISBN 978–951–25–2257–6 ISBN 978–951–25–2258–3 (PDF) ISSN 1797–8629 Printed in Finland Juvenens Print Oy Tampere 2011 3 Contents Jukka Tuononen Preface .............................................................................................5 Mikaeli Langinvainio Introduction .....................................................................................8 Mikko Laakkonen Military Crisis Management in the Next Decade (2020–2030) ..............................................................12 Antti Häikiö New Military and Civilian Training - What can they learn from each other? What should they learn together? And what must both learn? .....................................................................................20 Petteri Kurkinen Concept for the PfP Training