Abelson – the Invention of Kleptomania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012-Fall.Pdf

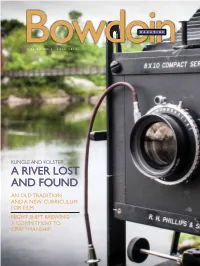

MAGAZINE BowdoiVOL.84 NO.1 FALL 2012 n KLINGLE AND KOLSTER A RIVER LOST AND FOUND AN OLD TRADITION AND A NEW CURRICULUM FOR FILM NIGHT SHIFT BREWING: A COMMITMENT TO CRAFTMANSHIP FALL 2012 BowdoinMAGAZINE CONTENTS 14 A River Lost and Found BY EDGAR ALLEN BEEM PHOTOGRAPHS BY BRIAN WEDGE ’97 AND MIKE KOLSTER Ed Beem talks to Professors Klingle and Kolster about their collaborative multimedia project telling the story of the Androscoggin River through photographs, oral histories, archival research, video, and creative writing. 24 Speaking the Language of Film "9,)3!7%3%,s0(/4/'2!0(3"9-)#(%,%34!0,%4/. An old tradition and a new curriculum combine to create an environment for film studies to flourish at Bowdoin. 32 Working the Night Shift "9)!.!,$2)#(s0(/4/'2!0(3"90!40)!3%#+) After careful research, many a long night brewing batches of beer, and with a last leap of faith, Rob Burns ’07, Michael Oxton ’07, and their business partner Mike O’Mara, have themselves a brewery. DEPARTMENTS Bookshelf 3 Class News 41 Mailbox 6 Weddings 78 Bowdoinsider 10 Obituaries 91 Alumnotes 40 Whispering Pines 124 [email protected] 1 |letter| Bowdoin FROM THE EDITOR MAGAZINE Happy Accidents Volume 84, Number 1 I live in Topsham, on the bank of the Androscoggin River. Our property is a Fall 2012 long and narrow lot that stretches from the road down the hill to our house, MAGAZINE STAFF then further down the hill, through a low area that often floods when the tide is Editor high, all the way to the water. -

Professional Criminals of America

D\\vv Cornell University Library XI The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924096989177 In compliance with current copyright law, Cornell University Library produced this replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Standard Z39.48-1992 to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. 2003 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY THIS BOOK IS ONE OF A COLLECTION MADE BY BENNO LOEWy I854-I9I9 AND BEQUEATHED TO CORNELL UNIVERSITY Professional Criminals of America. Negative by Andtrson, N. Y. J-TcIiMypc Pn'uiiijg Co., Boston. ^Ut^» PROFESSIONAL CRIMINALS OF AMERICA BY THOMAS BYRNES INSPECTOR OF POLICE AND CHIEF OF DETECTIVES NEW YORK CITY 'PRO BONO PUBLICO' CASSELL & COMPANY, Limited 739 & 741 BROADWAY. NEW YORK Copyright, 1886, By THOMAS BYRNES. All rights reserved. PRESS OF HUNTER & BEACH, NEW YORK. , ^^<DOeytcr-^ /fA.Cri^i.<^Ci^ //yrcpri^t^e^ (^u^ e-^e^.y^ INTRODUCTION. THE volume entitled "Professional Criminals of America," now submitted to the public, is not a work of fiction, but a history of the criminal classes. The writer has confined himself to facts, collected by systematic investigation and verified by patient research, during a continuous, active and honorable service of nearly a quarter of a century in the Police Department of the City of New York. Necessarily, during this long period, Inspector Thomas Byrnes has been brought into official relations with professional thieves of all grades, and has had a most favorable field for investigating the antecedents, history and achievements of the many dangerous criminals continually preying upon the community. -

The Ann Arbor Democrat

THE ANN ARBOR DEMOCRAT. FIFTH YEAR. ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN, FRIDAY, JULY 27, 1883. NUMBER 254. A five-year-old son of Clark Webb, of Hud- which must have been fully 14 feet high, and to who will be the next senator from the old TOPICS OF THE TIMES. MICHIGAN NEWS. son, swallowed a dose of corbolic acid, and died SEWS OF THE WEEK. probably weighed a third more than Jnmbo. Granite state puzzles the politicians. FOLK NOTES. in frightful 6pasms. The tusk, he says, must have been at Iea»t 11 AM ARBOR DEMOCRAT feet long. The animal lived in the post pli >- FROM THE GRANITE STATE. Miss Bessie Colby, of Froyburg. Me. Flushing is to have anew Methodist church. On Thursday July 19th, two votes were tak- Next November the Prince of Wales Class county farmers are jubilant because PMOM THE TOSTOFFICE DEPARTMENT. cene period of the tertiary age. Prof. Boynton •rill be 42 years. will be three rears old on Ausrust 9 thev have completed their wheat harvest and A Rather ffllied Affair is of the opinion that the remains were washeo en in the New Hampshire legi«tation foi have saved the crop in such good condition. In April last one Sturdifant began proceed- Postmasters thoughout the country have into the gravel pit where they were found United States Senator. On the first ballot Gen. Grant's mother left an estate A few days ago she encountered a pois been notified to begii. preparations for theProf. Brown, instructor in natural history at Brigham received 114 and Chandler 79; on thi Chas. -

The Biography of Sophie Lyons (1848-1924)

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 Queen of the Underworld: The Biography of Sophie Lyons (1848-1924) Barbara M. Gray Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/424 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] QUEEN OF THE UNDERWORLD: THE BIOGRAPHY OF SOPHIE LYONS (1848-1924) By BARBARA GRAY A master's thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 BARBARA GRAY All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Date________________ __________________________________________ Shifra Sharlin, Thesis Advisor Date________________ __________________________________________ Matthew Gold, Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract QUEEN OF THE UNDERWORLD: THE BIOGRAPHY OF SOPHIE LYONS (1848-1924) by Barbara Gray Advisor: Professor Shifra Sharlin Sophie Lyons was a nineteenth-century American pickpocket, blackmailer, con-woman, and bank robber. She was raised in New York City’s underworld, by Jewish immigrant parents who were criminals that trained their children to pick pockets and shoplift. “Pretty Sophie” possessed a rare combination of skill at thievery, intellect, guts and beauty and became the woman Herbert Ashbury described in Gangs of New York as, "the most notorious confidence woman America has ever produced." Newspapers around the world chronicled Sophie’s exploits for more than sixty years, because her life read like a novel. -

1 Respectable White Ladies, Wayward Girls, and Telephone

Respectable White Ladies, Wayward Girls, and Telephone Thieves in Miami’s “Case of the Clinking Brassieres” Dr. Vivien Miller American & Canadian Studies, University of Nottingham In her landmark study of gender, family life, and domestic containment in the United States during the 1940s and 1950s, historian Elaine Tyler May noted the importance of the consumer, arms, and space races for Cold War Americans: “Family-centred spending was encouraged as a way of strengthening “the American way of life,” and thus fostering traditional, nuclear family and patriarchal values, and patriotism.1 A “fetishization of commodities” was integral to the new post-war national identity and the “feminine mystique” embodied the resurgence of neo-Victorian domesticity and motherhood.2 In 1947, journalist Ferdinand Lundberg and psychiatrist Marynia Farnham asserted that it was women’s nature to be passive and dependent. Female happiness was attained through marriage, homemaking and motherhood, while societal disarray was linked to female employment outside the home.3 Sociologist Wini Breines notes that a good life in the 1950s “was defined by a well- equipped house in the suburbs, a new car or two, a good white-collar job for the husband, well-adjusted and successful children taken care of by a full-time wife and mother. Leisure time and consumer goods constituted its centrepieces; abundance was its context. White skin was a criterion for its attainment.”4 The post-war US economy as measured by the purchase 1 Elaine Tyler May, Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era, (New York: Basic Books, 1988), especially Ch7: The Commodity Gap: Consumerism and the Modern Home, 162-182. -

American Images of Childhood in an Age of Educational and Social

AMERICAN IMAGES OF CHILDHOOD IN AN AGE OF EDUCATIONAL AND SOCIAL REFORM, 1870-1915 By AMBER C. STITT Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art History and Art CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May 2013 2 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the dissertation of Amber C. Stitt, candidate for the PhD degree*. _________________Henry Adams________________ (chair of the committee) _________________Jenifer Neils_________________ _________________Gary Sampson_________________ _________________Renée Sentilles_________________ Date: March 8, 2013 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 3 Table of Contents: List of Figures 11. Acknowledgments 38. Abstract 41. Introduction 43. Chapter I 90. Nineteenth-Century Children’s Social Reform 86. The Cruel Precedent. 88. The Cultural Trope of the “Bad Boy” 92. Revelations in Nineteenth-Century Childhood Pedagogy 97. Kindergarten 90. Friedrich Froebel 91. Froebel’s American Champions 93. Reflections of New Pedagogy in Children’s Literature 104. Thomas Bailey Aldrich 104. Mark Twain 107. The Role of Gender in Children’s Literature 110. Conclusions 114. Chapter II 117. Nineteenth-Century American Genre Painters 118. Predecessors 118. Early Themes of American Childhood 120. The Theme of Family Affection 121. 4 The Theme of the Stages of Life 128. Genre Painting 131. George Caleb Bingham 131. William Sidney Mount 137. The Predecessors: A Summary 144. The Innovators: Painters of the “Bad Boy” 145. Eastman Johnson 146. Background 147. Johnson’s Early Images of Children 151. The Iconic Work: Boy Rebellion 160. Johnson: Conclusions 165. Winslow Homer 166. Background 166. -

The Reserve Advocate, 07-08-1922 A

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Reserve Advocate, 1921-1923 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 7-8-1922 The Reserve Advocate, 07-08-1922 A. H. Carter Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/reserve_advocate_news Recommended Citation Carter, A. H.. "The Reserve Advocate, 07-08-1922." (1922). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/reserve_advocate_news/38 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reserve Advocate, 1921-1923 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ONLY NEWSPAPER SMILE "AND THE PUBLISHED IN RESERVE ADVOCATE WORLD SMILES . WITH YOU CATRON COUNTY, N. M. NO NEED OF WEEPING VOL 10 TWO DOLLARS A YEAR RESERVE, CATRON COUNTY. NEW MEXICO, JULY 8, 1922, NO. 11 Business and Politics of Kind. .dining Co. Mogollon, N. M. When My Ship Gomes In is a the Right u is Well to Elect Good Men to Office. We Can Then Candalario Chavez, Mangus picture-yt- will enjoy to the THE RESERVE ADVOCATE It Chas Adair Luna Valley limit. Full of and it on pathos fun, Expect Proper Return the Investment. Sesario Sanchez Horse Springs. hay a puu on your heart Strings. RESERVE PUBLISHING PUBLISHERS. in COMPANY, from over the entire business is Conklin the Dynamiter is J. E. RHFIN, EDITOR AND GENERAL MANAGER Rprts ciuntry indicatejthat Amended List a scream. coming back to normal. By that is meant not alone .that every bus- f No. 2. " Come and laugh with us, Puplishedjevery Thursday at the tiaunt Buildiug, Reserve, New Mexico, iness ia more less prosperous, but that such prosperity is depend RESTORATION TO ENTRY OF week we Mon second-cias- able and will containue so long as the general public has confidence LAiNiJS IN NATIONAL FOREST. -

The Right Way to Do Wrong " May Amuse and Entertain My Readers and Place the Unwary on Their Guard

? I ' -J TUKT 'SI fc* M i\*^ iuii T Wi I '/ AN EXPOSE OF - SUCCESSFUL CRIMINALS BY HARRY KOUDINI Published by / HARRY HOUDINI BOSTON.MASS.U.&A. 1906 (yi) <*-. .-. A r; > ' v ScC^QU'i hAnk«>.0 COUEGE LIBRARY FROM THE BEQUEST OF EVERT MNSEN WENDELL • 918 COPYRIGHT, 1906, BY HARRY HOUDINI Illustrated by Henry Crossman Grover Printed by The Barta Press, Boston ■ . — •. " . I ,1 '* : \ * V' \ * \' \ \ \ \\ ; . _^^ , " (.. /^ . ' w- . ! . ' : i ,,. ^ .,., __,__ ,_. ..-.-. ' > »T 4. FLtMlttO- CHICAOO HARRY HOUDINI PREFACE »!V.Vi O would the deed were good I For now the Devil- that told me I did well, Says that this deed is chronicled in Hell I — Shakespeare. HERE is an under world — a world of cheat and crime — a world whose highest good is successful evasion of the laws of the land. You who live your life in placid respecta bility know but little of the real life of the denizens of this world. The daily records of the police courts, the startling disclosures of fraud and swindle in newspaper stories are about all the public know of this world of crime. Of the real thoughts and feelings of the criminal, of the terrible fascination which binds him to his nefarious career, of the thousands — yea, tens of thousands — of undiscovered crimes and unpunished criminals, you know but little. The object of this book is twofold : First, to safeguard the public against the practises of the criminal classes by exposing their various tricks and explaining the adroit methods by which they seek to defraud. "Knowledge is power " is an old saying.