Species Profile: Quercus Cedrosensis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malosma Laurina (Nutt.) Nutt. Ex Abrams

I. SPECIES Malosma laurina (Nutt.) Nutt. ex Abrams NRCS CODE: Family: Anacardiaceae MALA6 Subfamily: Anacardiodeae Order: Sapindales Subclass: Rosidae Class: Magnoliopsida Immature fruits are green to red in mid-summer. Plants tend to flower in May to June. A. Subspecific taxa none B. Synonyms Rhus laurina Nutt. (USDA PLANTS 2017) C. Common name laurel sumac (McMinn 1939, Calflora 2016) There is only one species of Malosma. Phylogenetic analyses based on molecular data and a combination of D. Taxonomic relationships molecular and structural data place Malosma as distinct but related to both Toxicodendron and Rhus (Miller et al. 2001, Yi et al. 2004, Andrés-Hernández et al. 2014). E. Related taxa in region Rhus ovata and Rhus integrifolia may be the closest relatives and laurel sumac co-occurs with both species. Very early, Malosma was separated out of the genus Rhus in part because it has smaller fruits and lacks the following traits possessed by all species of Rhus : red-glandular hairs on the fruits and axis of the inflorescence, hairs on sepal margins, and glands on the leaf blades (Barkley 1937, Andrés-Hernández et al. 2014). F. Taxonomic issues none G. Other The name Malosma refers to the strong odor of the plant (Miller & Wilken 2017). The odor of the crushed leaves has been described as apple-like, but some think the smell is more like bitter almonds (Allen & Roberts 2013). The leaves are similar to those of the laurel tree and many others in family Lauraceae, hence the specific epithet "laurina." Montgomery & Cheo (1971) found time to ignition for dried leaf blades of laurel sumac to be intermediate and similar to scrub oak, Prunus ilicifolia, and Rhamnus crocea; faster than Heteromeles arbutifolia, Arctostaphylos densiflora, and Rhus ovata; and slower than Salvia mellifera. -

The Collection of Oak Trees of Mexico and Central America in Iturraran Botanical Gardens

The Collection of Oak Trees of Mexico and Central America in Iturraran Botanical Gardens Francisco Garin Garcia Iturraran Botanical Gardens, northern Spain [email protected] Overview Iturraran Botanical Gardens occupy 25 hectares of the northern area of Spain’s Pagoeta Natural Park. They extend along the slopes of the Iturraran hill upon the former hay meadows belonging to the farmhouse of the same name, currently the Reception Centre of the Park. The minimum altitude is 130 m above sea level, and the maximum is 220 m. Within its bounds there are indigenous wooded copses of Quercus robur and other non-coniferous species. Annual precipitation ranges from 140 to 160 cm/year. The maximum temperatures can reach 30º C on some days of summer and even during periods of southern winds on isolated days from October to March; the winter minimums fall to -3º C or -5 º C, occasionally registering as low as -7º C. Frosty days are few and they do not last long. It may snow several days each year. Soils are fairly shallow, with a calcareous substratum, but acidified by the abundant rainfall. In general, the pH is neutral due to their action. Collections The first plantations date back to late 1987. There are currently approximately 5,000 different taxa, the majority being trees and shrubs. There are around 3,000 species, including around 300 species from the genus Quercus; 100 of them are from Mexico and Central America. Quercus costaricensis photo©Francisco Garcia 48 International Oak Journal No. 22 Spring 2011 Oaks from Mexico and Oaks from Mexico -

DISCUSSION of the FLORA of GUADALUPE ISLAND Dr. Reid Moran1

DISCUSSION OF THE FLORA OF GUADALUPE ISLAND Dr. Reid Moran1: Guadalupe Island lies about 250 miles south- southwest of San Diego, California, and about 160 miles off the peninsula of Baja California, Mexico. Volcanic in origin and sep arated from the peninsula by depths of about 12,000 feet, it is clearly an oceanic island. Among the vascular plants recorded from Guadalupe Island and its islets, apparently 164 species are native. Goats, introduced more than a century ago, have eliminated some species and re duced others nearly to extinction. Outer Islet, a goatless refugium two miles south of the main island, has a native florula of 36 species. Nine of these (including Euphorbia misera and Lavatera occidentalis) are very scarce on the main island, largely confined to cliffs inaccessible to goats; another one (Coreopsis gigantea) has not been collected there since 1875; and five others (includ ing Lavatera lindsayi, Dudleya guadalupensis, and Rhus integri¬ folia) have never been recorded from there. Although it is not known that these five ever did occur on the main island, presum ably they did but were exterminated by the goats. These five, comprising 14 per cent of the native florula of Outer Islet, give the only suggestion we have as to how many species must have been eliminated from the main island by the goats before they could be found by botanists. Also reported from Guadalupe Island are 42 species that prob ably are not native. Several of these, each found only once, ap parently have not persisted; but, with the severe reduction of many native plants by the goats, other introduced plants have become abundant. -

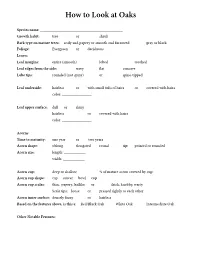

How to Look at Oaks

How to Look at Oaks Species name: __________________________________________ Growth habit: tree or shrub Bark type on mature trees: scaly and papery or smooth and furrowed gray or black Foliage: Evergreen or deciduous Leaves Leaf margins: entire (smooth) lobed toothed Leaf edges from the side: wavy fat concave Lobe tips: rounded (not spiny) or spine-tipped Leaf underside: hairless or with small tufs of hairs or covered with hairs color: _______________ Leaf upper surface: dull or shiny hairless or covered with hairs color: _______________ Acorns Time to maturity: one year or two years Acorn shape: oblong elongated round tip: pointed or rounded Acorn size: length: ___________ width: ___________ Acorn cup: deep or shallow % of mature acorn covered by cup: Acorn cup shape: cap saucer bowl cup Acorn cup scales: thin, papery, leafike or thick, knobby, warty Scale tips: loose or pressed tightly to each other Acorn inner surface: densely fuzzy or hairless Based on the features above, is this a: Red/Black Oak White Oak Intermediate Oak Other Notable Features: Characteristics and Taxonomy of Quercus in California Genus Quercus = ~400-600 species Original publication: Linnaeus, Species Plantarum 2: 994. 1753 Sections in the subgenus Quercus: Red Oaks or Black Oaks 1. Foliage evergreen or deciduous (Quercus section Lobatae syn. 2. Mature bark gray to dark brown or black, smooth or Erythrobalanus) deeply furrowed, not scaly or papery ~195 species 3. Leaf blade lobes with bristles 4. Acorn requiring 2 seasons to mature (except Q. Example native species: agrifolia) kelloggii, agrifolia, wislizeni, parvula 5. Cup scales fattened, never knobby or warty, never var. -

The Conservation of Forest Genetic Resources Case Histories from Canada, Mexico, and the United States

The Conservation of Forest Genetic Resources Case Histories from Canada, Mexico, and the United States value of gene banks in the conservation of forest genetic resources. By E Thomas Ledig, J.JesusVargas-Hernandez, and Kurt H. Johnsen Prepared as a task of the Forest Genetic Resources Study Group/North American Forestry CornrnissioniFood and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Reprinted from the Joul-rzal of Forestry, Vol. 96, No. 1, January 1998. Not for further reproduction. e Conservation of Forest Case Histories from Canada, Mexico, and the United States he genetic codes of living organ- taken for granted: release of oxygen and isms are natural resources no less storage of carbon, amelioration of cli- T than soil, air, and water. Genetic mate, protection of watersheds, and resources-from nucleotide sequences others. Should genetic resources be lost, in DNA to selected genotypes, popula- ecosystem function may also be dam- tions, and species-are the raw mater- aged, usually expressed as a loss of pri- ial in forestry: for breeders, for the for- mary productivity, the rate at which a est manager who produces an eco- plant community stores energy and pro- nomic crop, for society that reaps the duces organic matter (e.g., Fetcher and environmental benefits provided by Shaver 1990). Losses in primary pro- forests, and for the continued evolu- ductivity result in changes in nutrient tion of the species itself. and gas cycling in Breeding, of course, The loss g~f;a ecosystems (Bormann requires genetic variation. and Likens 1979). Continued improvement p population is Genetic diversity is in medicines, agricultural the most basic element By F. -

And Engelmann Oak (Q. Engelmannii) at the Acorn and Seedling Stage1

Insect-oak Interactions with Coast Live Oak (Quercus agrifolia) and Engelmann Oak (Q. engelmannii) at the Acorn and Seedling Stage1 Connell E. Dunning,2 Timothy D. Paine,3 and Richard A. Redak3 Abstract We determined the impact of insects on both acorns and seedlings of coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia Nee) and Engelmann oak (Quercus engelmannii E. Greene). Our goals were to (1) identify insects feeding on acorns and levels of insect damage, and (2) measure performance and preference of a generalist leaf-feeding insect herbivore, the migratory grasshopper (Melanoplus sanguinipes [Fabricus] Orthoptera: Acrididae), on both species of oak seedlings. Acorn collections and insect emergence traps under mature Q. agrifolia and Q. engelmannii revealed that 62 percent of all ground-collected acorns had some level of insect damage, with Q. engelmannii receiving significantly more damage. However, the amount of insect damage to individual acorns of both species was slight (<20 percent damage per acorn). Curculio occidentis (Casey) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), Cydia latiferreana (Walsingham) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae), and Valentinia glandulella Riley (Lepidoptera: Blastobasidae) were found feeding on both species of acorns. No-choice and choice seedling feeding trials were performed to determine grasshopper performance on the two species of oak seedlings. Quercus agrifolia seedlings and leaves received more damage than those of Q. engelmannii and provided a better diet, resulting in higher grasshopper biomass. Introduction The amount of oak habitat in many regions of North America is decreasing due to increased urban and agricultural development (Pavlik and others 1991). In addition, some oak species are exhibiting low natural regeneration. Although the status of Engelmann oak (Quercus engelmannii E. -

Engelmann Oak Survey Report 2018

Western Riverside County Multiple Species Habitat Conservation Plan Biological Monitoring Program 2018 Engelmann Oak (Quercus engelmannii) Recruitment Survey Report 25 February 2019 2018 Engelmann Oak Recruitment Survey Report TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 1 GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ................................................................................................................... 1 METHODS ............................................................................................................................ 2 PROTOCOL DEVELOPMENT ................................................................................................................ 2 STUDY SITE SELECTION ..................................................................................................................... 2 SURVEY METHODS ............................................................................................................................ 3 TRAINING ........................................................................................................................................... 4 DATA ANALYSIS ................................................................................................................................ 5 RESULTS .............................................................................................................................. 5 DISCUSSION ...................................................................................................................... -

Previously Unrecorded Damage to Oak, Quercus Spp., in Southern California by the Goldspotted Oak Borer, Agrilus Coxalis Waterhouse (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) 1 2 TOM W

THE PAN-PACIFIC ENTOMOLOGIST 84(4):288–300, (2008) Previously unrecorded damage to oak, Quercus spp., in southern California by the goldspotted oak borer, Agrilus coxalis Waterhouse (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) 1 2 TOM W. COLEMAN AND STEVEN J. SEYBOLD 1USDA Forest Service-Forest Health Protection, 602 S. Tippecanoe Ave., San Bernardino, California 92408 Corresponding author: e-mail: [email protected] 2USDA Forest Service-Pacific Southwest Research Station, Chemical Ecology of Forest Insects, 720 Olive Dr., Suite D, Davis, California 95616 e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. A new and potentially devastating pest of oaks, Quercus spp., has been discovered in southern California. The goldspotted oak borer, Agrilus coxalis Waterhouse (Coleoptera: Buprestidae), colonizes the sapwood surface and phloem of the main stem and larger branches of at least three species of Quercus in San Diego Co., California. Larval feeding kills patches and strips of the phloem and cambium resulting in crown die back followed by mortality. In a survey of forest stand conditions at three sites in this area, 67% of the Quercus trees were found with external or internal evidence of A. coxalis attack. The literature and known distribution of A. coxalis are reviewed, and similarities in the behavior and impact of this species with other tree-killing Agrilus spp. are discussed. Key Words. Agrilus coxalis, California, flatheaded borer, introduced species, oak mortality, Quercus agrifolia, Quercus chrysolepis, Quercus kelloggii, range expansion. INTRODUCTION Extensive mortality of coast live oak, Quercus agrifolia Ne´e (Fagaceae), Engelmann oak, Quercus engelmannii Greene, and California black oak, Q. kelloggii Newb., has occurred since 2002 on the Cleveland National Forest (CNF) in San Diego Co., California. -

From the Late Miocene-Early Pliocene (Hemphillian) of California

Bull. Fla. Mus. Nat. Hist. (2005) 45(4): 379-411 379 NEW SKELETAL MATERIAL OF THALASSOLEON (OTARIIDAE: PINNIPEDIA) FROM THE LATE MIOCENE-EARLY PLIOCENE (HEMPHILLIAN) OF CALIFORNIA Thomas A. Deméré1 and Annalisa Berta2 New crania, dentitions, and postcrania of the fossil otariid Thalassoleon mexicanus are described from the latest Miocene–early Pliocene Capistrano Formation of southern California. Previous morphological evidence for age variation and sexual dimorphism in this taxon is confirmed. Analysis of the dentition and postcrania of Thalassoleon mexicanus provides evidence of adaptations for pierce feeding, ambulatory terrestrial locomotion, and forelimb swimming in this basal otariid pinniped. Cladistic analysis supports recognition of Thalassoleon as monophyletic and distinct from other basal otariids (i.e., Pithanotaria, Hydrarctos, and Callorhinus). Re-evaluation of the status of Thalassoleon supports recognition of two species, Thalassoleon mexicanus and Thalassoleon macnallyae, distributed in the eastern North Pacific. Recognition of a third species, Thalassoleon inouei from the western North Pacific, is questioned. Key Words: Otariidae; pinniped; systematics; anatomy; Miocene; California INTRODUCTION perate, with a very limited number of recovered speci- Otariid pinnipeds are a conspicuous element of the ex- mens available for study. The earliest otariid, tant marine mammal assemblage of the world’s oceans. Pithanotaria starri Kellogg 1925, is known from the Members of this group inhabit the North and South Pa- early late Miocene (Tortonian Stage equivalent) and is cific Ocean, as well as portions of the southern Indian based on a few poorly preserved fossils from Califor- and Atlantic oceans and nearly the entire Southern nia. The holotype is an impression in diatomite of a Ocean. -

Southern Exposures

Searching for the Pliocene: Southern Exposures Robert E. Reynolds, editor California State University Desert Studies Center The 2012 Desert Research Symposium April 2012 Table of contents Searching for the Pliocene: Field trip guide to the southern exposures Field trip day 1 ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 5 Robert E. Reynolds, editor Field trip day 2 �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 19 George T. Jefferson, David Lynch, L. K. Murray, and R. E. Reynolds Basin thickness variations at the junction of the Eastern California Shear Zone and the San Bernardino Mountains, California: how thick could the Pliocene section be? ��������������������������������������������������������������� 31 Victoria Langenheim, Tammy L. Surko, Phillip A. Armstrong, Jonathan C. Matti The morphology and anatomy of a Miocene long-runout landslide, Old Dad Mountain, California: implications for rock avalanche mechanics �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 38 Kim M. Bishop The discovery of the California Blue Mine ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 44 Rick Kennedy Geomorphic evolution of the Morongo Valley, California ���������������������������������������������������������������������������� 45 Frank Jordan, Jr. New records -

Southern Oak Woodlands of the Santa Rosa Plateau, Riverside County, California Earl W

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 10 | Issue 4 Article 8 1984 Southern Oak Woodlands of the Santa Rosa Plateau, Riverside County, California Earl W. Lathrop Henry A. Zuill Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Lathrop, Earl W. and Zuill, Henry A. (1984) "Southern Oak Woodlands of the Santa Rosa Plateau, Riverside County, California," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 10: Iss. 4, Article 8. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol10/iss4/8 ALISO 10(4), 1984, pp. 603-611 SOUTHERN OAK WOODLANDS OF THE SANTA ROSA PLATEAU, RIVERSIDE COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Earl W. Lathrop and Henry A. Zuill INTRODUCTION The Santa Rosa Plateau is a distinct topographic unit located at the south eastern end of the Santa Ana Mountains (Lathrop and Thome 1968). The southern oak woodland community in the Santa Ana Mountains is closely associated with grasslands, but mainly occurs from Los Pinos and El Cariso southward, with its greatest development on the Santa Rosa Plateau (Lathrop and Thome 1968). Quercus engelmannii Greene (Engelmann oak, Fig. 1) and Q. agrifolia Nee (coast live oak, Fig. 2) are dominant in this community with associated species of Ceanothus, Rhus, Ribes, and other shrubby genera, intruding from the chaparral (Thome 1976). Lathrop and Thome (1978) presented a brief account of species associated with the oak woodlands on Mesa de Burro of the Santa Rosa Plateau. Snow ( 1972, 1979) and Zuill (1967) reported on distribution and structure of Q. engelmannii and Q. agrifolia on the plateau. -

Lemonade Berry

Native Plants in the South Pasadena Nature Park - #1 Powerpoint Presentation and Photographs by Barbara Eisenstein, October 23, 2012 To identify plants use some of your senses (and your common sense): Look at: plant size and shape ۵ leaf size, shape, color, texture and arrangement ۵ flower types, color, arrangement ۵ Touch (with care): fuzzy or smooth leaves ۵ stiff or flexible stems ۵ Smell: Many California plants have very distinctive odors especially in their leaves ۵ Some weeds are easily distinguished from natives by their smell ۵ Taste: !!!Never taste a plant you are unsure of. Some plants are poisonous ۵ Listen: .Rustling leaves can be hint ۵ NATIVE TREES AND LARGE SHRUBS • Coast live oak • Sugar bush • Engelmann oak • Laurel sumac • So. CA black walnut • Lemonade berry • Western sycamore • Yellow willow • Blue elderberry • Holly-leaf cherry • Toyon NATIVE Coast Live Oak (Quercus agrifolia) • Key Identifying Traits: Broad, evergreen oak tree with dark green leaves. Leaves cupped, green above, usually lighter beneath, with spines on margin Trunk is massive with gray bark. Tree, height: up to 30’, width: 35’ • Other facts: Magnificent native tree. Resistant to many pests and diseases but susceptible to oak root fungus (Armillaria mellea). To protect from root fungus, water established trees infrequently but deeply and avoid summer water. • May be confused with: Other oaks. Cupped leaves with spiny margins distinguish this oak. Bark is often smooth gray but in mature trees can be rough and variable. NATIVE Engelmann oak (Quercus engelmannii) • Key Identifying Traits: Drought deciduous tree, height: rarely taller than 40 ft., width: mature tree broader than tall.