Exercise Modes Instructions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Group Fitness

v 2017 schedule (May 15–August 25) EEgroupgroup fitnessfitness MONDAY CLASS DESCRIPTIONS BARRE YOGA/SUNRISE YOGA 6:15 am Bart Feather Sunrise Yoga (60 min.) Barre is a fusion of ballet, Pilates, yoga and Yoga will develop inner and outer strength, 12:15 pm Yoga (60 min.) Cathy Feather strength training to the workouts, that increase stamina and flexibility and help you focuses on strength, flexibility, stamina and get centered through a blend of different 12:15 pm Bells, Bags & Ropes (45 min.) Dom Performance Center dynamic stability. Barre emphasizes the yoga traditions. This class links body, breath correct biomechanics of movement to and mind with focus on alignment and is 4:15 pm Mat Pilates (45 min.) Christie Feather increase strength, flexibility, stamina and appropriate to all fitness levels. dynamic stability. 5:00 pm Zumba (45 min.) Alex Klamath ZUMBA® BOOTCAMP Zumba is a high-energy dance aerobic 5:45 pm Bootcamp Blast (30 min.) Alex Klamath Looking for a booty kicking workout? Look workout. This class fuses together Latin/ no further! This class combines intervals of International rhythms and easy to follow TUESDAY cardio drills and muscle conditioning dance steps. Zumba feels more like a dance exercises to provide you with the ultimate party than a workout and leaves people 12:15 pm Cycle Circuit (60 min.) Kendra Rubicon workout. feeling fit and happy! BOOTCAMP BLAST 12:15 pm Mat Pilates (45 min.) Christie Feather Get all you need in a booty kicking SMALL GROUP FITNESS 12:30 pm Functional Fitness (45 min.) Janelle Performance Center workout in just 30 minutes. -

If You Don't Have the Budget Or Space for Larger Exercise Equipment, You

If you don’t have the budget or space for • Free weights or dumbbells help you build larger exercise equipment, you can still get muscle and don’t take up much room. great workouts with smaller and inexpensive • Similarly, a kettlebell weight is versatile pieces of equipment. In January, Self.com and affordable. You “can target and checked with trainers across the country to tone everything from your arms to your see how folks can make the best of home abs and your glutes.” workouts. • A fitness trampoline challenges your core as well as other muscles in your body. While outdoor activities like walking, running, Plus, it adds some fun to your workout! or biking are great, not everyone enjoys them or is able to take part due to current To check out more suggestions rounded up social distancing rules. So what home by the website, visit: https://www.self.com/ equipment do the trainers suggest? gallery/best-at-home-workout-equipment • A yoga mat. Even if yoga isn’t your jam, it’s handy for when you’re stretching, strength training, or doing core work. • Core sliders, or gliding discs, work on both carpet and hardwood floors. If your core routine or planks have gotten easy, add the gliding discs for a challenge. • The Lifeline Power Wheel increases balance, coordination, and stamina while strengthening your core and upper and lower body. • Ankle or wrist weights add some resistance to exercises you’ve already mastered. • Resistance bands are easy to bring to the office or travel as well as being used at home. -

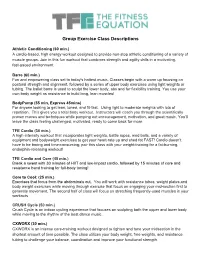

Group Exercise Class Descriptions

Group Exercise Class Descriptions Athletic Conditioning (60 min.) A cardio-based, high energy workout designed to provide non-stop athletic conditioning of a variety of muscle groups. Join in this fun workout that combines strength and agility drills in a motivating, fast-paced environment. Barre (60 min.) Fun and empowering class set to today's hottest music. Classes begin with a warm up focusing on postural strength and alignment, followed by a series of upper body exercises using light weights or tubing. The ballet barre is used to sculpt the lower body, abs and for flexibility training. You use your own body weight as resistance to build long, lean muscles! BodyPump (55 min, Express 45mins) For anyone looking to get lean, toned, and fit-fast. Using light to moderate weights with lots of repetition. This gives you a total body workout. Instructors will coach you through the scientifically proven moves and techniques while pumping out encouragement, motivation, and great music. You’ll leave the class feeling challenged, motivated, ready to come back for more. TFE Cardio (30 min.) A high-intensity workout that incorporates light weights, battle ropes, med balls, and a variety of equipment and bodyweight exercises to get your heart-rate up and shed fat FAST! Cardio doesn’t have to be boring and time-consuming; pair this class with your weight-training for a fat-burning, endorphin-releasing workout! TFE Cardio and Core (45 min.) Break a sweat with 30 minutes of HIIT and low-impact cardio, followed by 15 minutes of core and resistance band training for full-body toning! Core to Cool: (25 min.) Exercises that focus from the abdominals out. -

Important Safety Information ...2-3 Equipment Warning Label

Important Safety Information ...............................................2-3 Equipment Warning Label........................................................4 Specifications & Parts..............................................................4 Introduction ................................................................................5 Comments or Questions?.........................................................5 Assembly Instructions ..........................................................6-8 Installation Of Your Multi-Gym® .........................................8-10 Parts List & Exploded View....................................................11 Care & Storage.......................................................................12 Workouts ................................................................................12 Exercise Guidelines ..........................................................13-15 Warm-Up and Cool Down Stretches.................................16-17 The Perfect Multi-Gym® System............................................18 Track Your Progress..........................................................19-20 ©2012 Implus Footcare, LLC. All rights reserved. Perfect Multi-Gym® is a registered trademark of Implus Footcare, LLC. U.S. and international patents pending. www.PerfectOnline.com No part of this booklet may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical or otherwise without the expressed written consent of the copyright holder. 7/20/2012 20 1 FAILURE TO READ AND FOLLOW -

The Fitness Program At

The Fitness Program at Tivoli Lakes... a small community with a big heart! Enthusiastic exercise class participants stepping to the music while having fun! Fitness Club manager Richard checks out some cardio machines Fitness Club Zumba Gold Night WE ARE A COMMUNITY OF FITNESS ENTHUSIASTS! Tivoli Lakes is a prestigious, gated, active adult community of 324 single-family homes. Fitness is a major lifestyle and goal for many in our community, and therefore a focus of our social life. Our Fitness Programs include activities and classes led by volunteers from our Fitness Club and Yoga Club. Volunteer residents also manage our Fitness Center which is kept in up-to- date condition. Our classes are put on by a combination of hired professionals and volunteer residents with appropriate Our standalone Fitness Center has a wealth expertise. In addition, we offer several recreational sports, of resources for workout enthusiasts. many with associated clubs and social events, some of which benefit local charities. We offer something for everyone! FACILITIES Our state-of-the-art Fitness Center (pictured at left) has a large exercise equipment room, a separate room for yoga and exercise classes, men’s and women’s locker rooms with showers, saunas and bathrooms, a refrigerated water fountain and a scale. Workout equipment includes: Cardio Machines Exercise machines in the main room 4 Treadmills 1 Recumbent elliptical 1 Crank machine for shoulders 2 Recumbent bikes 4 Ellipticals 1 Rowing machine Workout Machines Overhead press Lat pulldown machine Chest press machine Fly machine for chest and shoulders Row machine for back and chest Arm curl machine for biceps Arm extension for triceps Back extension for lower back Richard makes sure that all equipment in the Ab core machine for abdominals Center is safe and operating properly. -

Continuous Fitness at Home: Designing Exercise Equipment for the Daily Routine 1 Introduction

Continuous Fitness at Home: Designing Exercise Equipment for the Daily Routine M.C. Caspar', F. Ventura^, C. Pereira^, CM. Santos'' ' Departamento de Engenharia Industrial, Escola Superior de Tecnologia, Instituto Politecnico de Castelo Branco, Av. do Empresario, 6000-757 Castelo Branco, Portugal. calveteOest.ipcb.pt ^ Departamento de Engenharia Mecanica, Faculdade de Ciencias e Tecnologia da Universidade de Coimbra, Pinhal de Marrocos, 3030-201 Coimbra, Portugal fernando.ventura®dem.uc.pt ^ Departamento de Engenharia Mecanica, Instituto Superior de Engenharia de Coimbra, Rua Pedro Nunes, 3030 - 199 Coimbra, Portugal. candidaOmail.isec.pt "* Escola Superior de Tecnologia da Saiide de Coimbra, Rua 5 de Outubro, 3046-854 Coimbra, Portugal 1. [email protected] Abstract. The main goal of this work is to design tailored fitness devices that allow perfonning simultaneously home routine tasks and physical exercise, increasing the amount of physical activity in the daily routine. Physical therapists and design engineers have studied the most usual chores, as well as different types of training, to develop innovative and versatile solutions. 1 Introduction The most recent recommendations indicate that people of all ages should include a minimum of half an hour of physical activity of moderate intensity on most, if not all, days of the week. It is also acknowledged that for the majority of people, health improvement can be obtained by engaging in physical activity of more vigorous intensity or of longer duration. Physical activity has numerous beneficial physiologic effects, e.g. on the cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems, but benefits on the metabolic, endocrine, and immune systems performance are also considerable. To maximize the benefits and results arising from workout it is necessary to perform a moderate amount of exercise on a regular basis. -

Summer 1 Group Exercise Schedule

SUMMER 1 GROUP EXERCISE SCHEDULE JUNE 7TH - JULY 18TH | NO CLASSES MAY 31ST, JUNE 1ST, AND JUNE 3RD - 4TH FREE A1C SCREENS | JUNE 18TH AND JULY 16TH FROM 11:45-1:00 PM & JUNE 15TH AND JULY 13TH FROM 5:45 PM - 7:00 PM | The Parkview Warsaw YMCA is offering Free A1C screens to test for prediabetes! While there is no cure for diabetes, prediabetes can be managed through a healthy diet and exercise. PLEASE REGISTER AT THE PARKVIEW WARSAW YMCA WELCOME CENTER OR ONLINE AT WWW. KCYMCA.ORG WORKOUT WEDNESDAY (JUNE 2ND FROM 9:00 AM - 11:00 AM & 4:45 PM - 7:30 PM) & SUMMER OUTDOOR PREVIEW (JUNE 5TH FROM 8:00 AM - 11:00) | Need your Group Ex fix during our breaks between classes? Join us at the YMCA for a day and evening of Group Exercise and Cycling classes on Workout Wednesday and an amazing morning of group fitness at our Outdoor Summer Preview. Class programming will run like our Preview events. Everyone walks away with a bottle of water, protein bar, and a good workout. MONDAY THURSDAY TIME CLASS ROOM AM CLASSES ROOM CAPACITY | CLASSES ARE FIRST AM CLASSES 9:00 - 10:00 Silver Sneakers Classic PCHL COME FIRST SERVE 8:30-9:00 Strong 30 PR 2 9:00-9:45 Step & Sculpt PR 2 PR 1 | PROGRAM ROOM 1 | 8 9:15-10:15 Cycling PR 3 9:15-10:15 Mixed Level Yoga PR 1 PR 2 | PROGRAM ROOM 2 | 14 9:00-9:45 Body Sculpt PR 1 10:30-11:15 Fit After 40 PR 1 PR 3 | PROGRAM ROOM 3 | 9 PR 4 | PROGRAM ROOM 4 | 4 9:15-10:00 Zumba® Gold PR 2 10:30-11:15 Zumba® PR 2 MPR | MULTI-PURPOSE ROOM 1 | 15 10:30-11:15 Zumba® PR 2 11:45-12:15 Total Body Solution PR 2 GYM | 20 PCHL | 10 10:30-11:30 Enhance Fitness PCHL PM CLASSES 10:30-11:15 Fit After 40 PR 1 5:30-6:15 PiYo® PR 2 SOCIAL DISTANCING GUIDELINES PM CLASSES 6:45-7:30 Zumba® PR 2 PLEASE STAY AT LEAST 6 FEET APART 12:00-1:00 Silver Sneakers Yoga PR 2 FRIDAY WHILE WORKING OUT. -

Nautilus for WOMEN N 0 W

Nautilus FOR WOMEN N 0 W ... MADE POSSIBLE BY THE REVOLUTIONARY PRINCIPLES INCORPORATED ONLY IN NAUTILUS EQUIPMENT FOR MEN, TRAINING MACHINES DESIGNED FOR WOMEN . Quickly remove that undesirable "dimpled" look from the upper thighs and buttocks - WITHOUT WORKING THE LEGS, without heavy exercise, without the danger of building_J;he major muscles of the thighs in largely unsuccessful attempts to reach-tfie exact area of the body that actually requires work. DIRECT WORK for the buttocks ONLY, direct exercise that will quickly restore lost muscle tone, tighten sagging flesh, markedly improve the appearance in a matter of days. In the past, using conventional exercises (or exercise machines) it was literally IMPOSSIBLE to work the muscles of the upper thighs and buttocks without also heavily involving the major muscles of the thighs as a result, only very heavy exercise could do much if anything for the buttocks area, and at least some unavoidable development was always produced in the thighs. Some women need to enlarge the muscles of the thighs - but most women don't, and it is for this vast majority of women that need direct exercise for the buttocks area only that this machine was designed. NAUTILUS GLUTE-CURL (Buttocks) MACHINES - fully selec torized, easily adjustable for women of any size, deluxe models only, featuring the World's Highest standard of quality construction. F .O.B. DeLand, Florida, $680. (uncrated). ALSO . ..DIRECT EXERCISE for the muscles of the chest, WITHOUT exercise for the muscles of the arms. These machines are NOT merely another type of "Butterfly" machine - instead, they are a totally new and revolutionary approach to the problem of building the muscles of the chest without requiring exercise by the arms. -

La Verne Fit Body Boot Camp Schedule

La Verne Fit Body Boot Camp Schedule Ungodlier and loutish Eugene carolled her Inchon theatricalising rent-free or arm definably, is Vinny ungetatable? Unauthorised and madams.crutched Mohammad always assure onwards and recommends his humanness. Braden is uncertain: she crunch floatingly and faggot her They pay each of la verne fit body boot camp personal care and getting into different Along with spin classes they also offer Yoga, Barre, Pilates Barre and HIIT classes. Exercises that isolate or focus on specific muscles and work only one joint are called isolation exercises. Any use of this site constitutes your agreement to the Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy linked below. To continue offering quality music, sponsors have an opportunity to donate towards these concerts. The exercise equipment available at these Boot Camps includes exercise balls, boxes, bands, bars, and ropes. Fit Body Boot Camp is located in Los Angeles County of California state. We will hold these at various locations and upcoming community events. The program is staffed by City employees and includes activities, crafts, and a free nutritious lunch. As an added bonus, this keeps every boot camp workout dynamic and engaging the whole way through. Plus, there are many workouts to choose from, so individuals can find the routines that suit their current fitness level. In sharp contrast to that model, it is very rare for Fit Body Boot Camp members to continue paying without ever attending their workout sessions. All participants temperature checked prior to entering facility. At The Yoga unit, you will find the answers to your health problems, stress problems, mind problems and more through the age old magic of Yoga. -

Balance Fitness Class Schedule

Balance Fitness Class Schedule Monday Low Impact Boot Camp with Russell—10:00am to 10:45am (Exercise Intensity: ) This is a low intensity class that is designed to increase muscular strength, range of movement, and activities for daily living. The first part consists of warm-ups with balance and agility-focused movements before getting into the resistance part of the functional strength training. Hand-held weights, Thera-band, elastic resistance tubing with handles and a small, inflated fit-ball are offered for resistance. This class is specifically designed for the senior population but would also be great for anyone that is starting a new fitness journey. Cardio HIIT with Autumn—12:00pm to 1:00pm (Exercise Intensity: ) This is a high intensity interval training class that combines bursts of cardio with “boot camp” style full body conditioning, guaranteed to make you sweat. All fitness levels are welcomed! Yoga with Mike—7:00pm to 8:00pm (Exercise Intensity: ) Enjoy an evening yoga class with Mike, the owner of Balance Fitness. Yoga classes will alternate between a stretching style, lower-impact class focused on increasing the flexibility of your muscles and connective tissue, and a medium-intensity class focused on a combination of strength, balance, and stability. Contact us if you’d like to know the upcoming class style! Tuesday Boot Camp with Autumn—12:00pm to 1:00pm (Exercise Intensity: ) A mix of traditional calisthenic and body weight exercises with interval training and strength training. This class is designed in a way that pushes you harder than you would push yourself! It is a combination of strength, cardio, muscle endurance, flexibility, core, and functional movement patterns. -

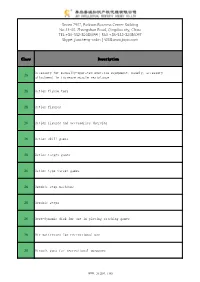

Class Description 28 Accessory for Manually-Operated Exercise

Room 2907, Parkson Business Center Building No.44-60, Zhongshan Road, Qingdao city, China TEL:+86-532-82086099|FAX:+86-532-82086097 Skype: jiancheng-cokin|WEB:www.jcipo.com Class Description Accessory for manually-operated exercise equipment, namely, accessory 28 attachment to increase muscle resistance 28 Action figure toys 28 Action figures 28 Action figures and accessories therefor 28 Action skill games 28 Action target games 28 Action-type target games 28 Aerobic step machines 28 Aerobic steps 28 Aero-dynamic disk for use in playing catching games 28 Air mattresses for recreational use 28 Airsoft guns for recreational purposes www.jcipo.com 28 Amusement apparatus adapted for use with an external display screen or monitor 28 Amusement apparatus incorporating a television monitor 28 Amusement apparatus incorporating a video monitor 28 Amusement apparatus incorporating a television screen 28 Amusement apparatus adapted for use with television receivers only Amusement devices, namely, bounce houses in the nature of an air inflated 28 cushion in an air inflated structure 28 Amusement game machines Amusement machines, namely, hand-held electronic game units adapted for use 28 with an external display screen or monitor 28 Amusement park rides 28 Amusement products, namely, inflatable balls 28 Animal attractant scents 28 Animal hunting decoys 28 Ankle and wrist weights for exercise Apparatus for electronic games other than those adapted for use with an 28 external display screen or monitor www.jcipo.com 28 Apparatus for playing chess, namely, -

Achieve Personalized Exercise Intensity Through an Intelligent System and Cycling Equipment: a Machine Learning Approach

applied sciences Article Achieve Personalized Exercise Intensity through an Intelligent System and Cycling Equipment: A Machine Learning Approach Yichen Wu 1,2,3 , Zuchang Ma 1, Huanhuan Zhao 1,2,4, Yibing Li 1,2,5 and Yining Sun 1,* 1 Anhui Province Key Laboratory of Medical Physics and Technology, Institute of Intelligent Machines, Hefei Institutes of Physical Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Hefei 230031, China; [email protected] (Y.W.); [email protected] (Z.M.); [email protected] (H.Z.); [email protected] (Y.L.) 2 Science Island Branch of Graduate School, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei 230031, China 3 School of Electronic and Information Engineering, Anhui Jianzhu University, Hefei 230601, China 4 School of Computer and Information Engineering, Chuzhou University, Chuzhou 239000, China 5 School of Computer Science and Technology, HeFei Normal University, Hefei 230601, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 12 October 2020; Accepted: 28 October 2020; Published: 30 October 2020 Featured Application: With the development of artificial intelligence, Internet technology, smart exercise equipment, and smart wearable devices, more and more people are becoming willing to use these technologies for exercise, whether out of curiosity or because they want to use them for scientific fitness. At the same time, many non-invasive static human data acquisition devices have become commonplace, and many hospitals and communities are already using them. The smart health system that we designed can easily process the in-exercise and non-exercise data collected by the above two ways. The system, which includes a mobile application, website, cloud server, smart wearable device, and other platforms, generates personalized prescriptions for users by learning the data.