Place of Renuka in Coastal Maharashtra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JUN 0 5 1992 U~T1an"R

MEANING IN ARCHITECTURE: AN INVESTIGATION OF THE INDIGENOUS ENVIRONMENT IN BANGLADESH SAIF-UL- HAQ Bachelor of Architecture Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology Dhaka, 1986 Submitted to the Department of Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Architecture Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June, 1992 @ Saif-ul- Haq, 1992 The author hereby grants to M.I.T. the permission to reproduce and distribute publicly copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Sdnature of Author Department of Architecture May 08, 1992 Saif-tIf- Haq Certified by Visiting Professor of Architecture, 'Ihesis Supervisor Ronald Bentley Lewcock Accepted by I Chairman, I Ibebartmental Committee for Graduate Students Julian Beinart Rotch MASSACHUSETS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUN 0 5 1992 U~t1An"r- MEANING IN ARCHITECTURE: AN INVESTIGATION OF THE INDIGENOUS ENVIRONMENT IN BANGLADESH Saif-ul- Haq Submitted to the Department of Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Architecture Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. June, 1992. ABSTRACT A meaningful environment forms a necessary and essential part of a meaningful existence. Meaning is an interpretive problem, and meaning in architecture is difficult to grasp. Theoretical insights into meaning have to be based on analysis of existing and historical environments. The history of great architecture is a description of man's search and discovery of meaning under different conditions. This, in turn, may be used to help improve today's understanding of architecture. This study is triggered by a fundamental need to understand the architecture of Bangladesh. -

A Study of the Early Vedic Age in Ancient India

Journal of Arts and Culture ISSN: 0976-9862 & E-ISSN: 0976-9870, Volume 3, Issue 3, 2012, pp.-129-132. Available online at http://www.bioinfo.in/contents.php?id=53. A STUDY OF THE EARLY VEDIC AGE IN ANCIENT INDIA FASALE M.K.* Department of Histroy, Abasaheb Kakade Arts College, Bodhegaon, Shevgaon- 414 502, MS, India *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: December 04, 2012; Accepted: December 20, 2012 Abstract- The Vedic period (or Vedic age) was a period in history during which the Vedas, the oldest scriptures of Hinduism, were composed. The time span of the period is uncertain. Philological and linguistic evidence indicates that the Rigveda, the oldest of the Vedas, was com- posed roughly between 1700 and 1100 BCE, also referred to as the early Vedic period. The end of the period is commonly estimated to have occurred about 500 BCE, and 150 BCE has been suggested as a terminus ante quem for all Vedic Sanskrit literature. Transmission of texts in the Vedic period was by oral tradition alone, and a literary tradition set in only in post-Vedic times. Despite the difficulties in dating the period, the Vedas can safely be assumed to be several thousands of years old. The associated culture, sometimes referred to as Vedic civilization, was probably centred early on in the northern and northwestern parts of the Indian subcontinent, but has now spread and constitutes the basis of contemporary Indian culture. After the end of the Vedic period, the Mahajanapadas period in turn gave way to the Maurya Empire (from ca. -

Challenging the Devadasi System from a Framework Of

CHALLENGING THE DEVADASI SYSTEM FROM A FRAMEWORK OF INTERSECTIONALITY A Dissertation by MRUDULA ANNE Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Jamie Callahan Committee Members, Lisa Baumgartner Dongxiao Liu Jia Wang Head of Department, Fredrick Nafukho December 2014 Major Subject: Educational Human Resource Development Copyright 2014 Mrudula Anne ABSTRACT The practice of marrying girls to deities or priests existed historically in many cultures across South Africa, Europe, and the Middle East. In India alone, this system is known by different names like Devadasi, Mathamma, Jogini, Basavis. Through this study, I represent the unheard voices of Devadasi women from South India and use HRD concepts and principles to synthesize the findings. The field of HRD is not confined to the boundaries of an organization and can play a critical role in community development. This is the first step towards empowering the members of this system and it is hoped that the findings from this study will help inform the organizational practices of NGO’s working with this populace. This study includes a unique set of participants whose experiences have not been captured and examined using intersectionality and Bourdieu, thus contributing to literature. Data was collected through interviews with Devadasi women from South India, specifically Nizamabad, Mahabubnagar, and Tirupati. Five themes emerged from the data – dichotomy, identity, status, fear and locus of control. The theme ‘status’ refers to the participant’s intersecting identities as women and as people from lower castes. -

Eeotheologieal Dimensions of Termite Hill

Eeotheologieal Dimensions of Termite Hill NANDKUMAR KAMAT ECOLOGY is most fundamental to the survival of human cultures and populations. Ecological resources are exploited by humans for creation of an artificial hierarchy of eco-systems. Technologies are evolved for efficient transfer of ecological resources. During this course of material and technological evolution symbols, motifs are absorbed; rituals are formulated, cults emerge through common symbols and rituals; gods and goddesses; demons and devils; spirits and angels assume forms and shapes and religious systems befitting the levels of technology get rooted. Magic is related to technology. Primitive agricultural and fertility magic could be considered as monopolised knowledge of stagnated, unevolved or dynamic technology depending upon the ecological specificity of each culture. The common determinants of ecological specificity of any region are soil and climate.1 The ecological dimensions of historical theology have to be examined from these common determinants. In this regard, the cults of earth-mother worship as found in South Konkan and Goa, could be test cases. Scientific elucidation of these cults and demystification of various beliefs, legends and rituals associated with them is necessary to find the true meaning of several historical phenomena. As A.C. Spawlding says, Hhistorians depend on a type of explanation that they claim is different from scientific explanation. While in fact, no separate form of historical explanation exists. "2 - Many quasi and pseudo-historical forms of explanations3 exist for the cult of Santeri, Ravalnatha, Skanda-Kartikeya, 84 Subhramanya and Muruga, Renuka, Parashurama and Yellamma, Jyotiba, Khandoba and Durga4. Mostly these are propagated through brahminic literature and sometimes through the folklore. -

Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples' Issues

Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples’ Issues Republic of India Country Technical Notes on Indigenous Peoples’ Issues REPUBLIC OF INDIA Submitted by: C.R Bijoy and Tiplut Nongbri Last updated: January 2013 Disclaimer The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IFAD concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The designations ‗developed‘ and ‗developing‘ countries are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. All rights reserved Table of Contents Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples‘ Issues – Republic of India ......................... 1 1.1 Definition .......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The Scheduled Tribes ......................................................................................... 4 2. Status of scheduled tribes ...................................................................................... 9 2.1 Occupation ........................................................................................................ 9 2.2 Poverty .......................................................................................................... -

Interpreting Sati: the Omplexc Relationship Between Gender and Power in India Cheyanne Cierpial Denison University

Denison Journal of Religion Volume 14 Article 2 2015 Interpreting Sati: The omplexC Relationship Between Gender and Power In India Cheyanne Cierpial Denison University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/religion Part of the Ethics in Religion Commons, and the Sociology of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Cierpial, Cheyanne (2015) "Interpreting Sati: The ompC lex Relationship Between Gender and Power In India," Denison Journal of Religion: Vol. 14 , Article 2. Available at: http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/religion/vol14/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Denison Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denison Journal of Religion by an authorized editor of Denison Digital Commons. Cierpial: Interpreting Sati: The Complex Relationship Between Gender and P INTERPRETING SATI: THE COMPLEX RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN GENDER AND POWER IN INDIA Interpreting Sati: The Complex Relationship Between Gender and Power In India Cheyanne Cierpial A recurring theme encountered in Hinduism is the significance of context sensitivity. In order to understand the religion, one must thoroughly examine and interpret the context surrounding a topic in Hinduism.1 Context sensitivity is nec- essary in understanding the role of gender and power in Indian society, as an exploration of patriarchal values, religious freedoms, and the daily ideologies as- sociated with both intertwine to create a complicated and elaborate relationship. The act of sati, or widow burning, is a place of intersection between these values and therefore requires in-depth scholarly consideration to come to a more fully adequate understanding. The controversy surrounding sati among religion schol- ars and feminist theorists reflects the difficulties in understanding the elaborate relationship between power and gender as well as the importance of context sen- sitivity in the study of women and gender in Hinduism. -

Chandogya Upanishad 1.2.1: Once Upon a Time the Gods and the Demons, Both Descendants of Prajapati, Were Engaged in a Fight

A Preview “… Dr. Prasad’s collections of the two largest and most difficult to understand Upanishads make an in-road and gives access to the magnificent conclusions left by the ancient sages of India. This book gives us a view of the information which was divulged by those teachers. It is easy to read and understand and will encourage you to delve deeper into the subject matter.” CONTENTS 1. Chāndogya Upanishad……..…….…. 3 1. The big famine…………………………….…..... 6 2. The cart-man…………………………….………13 3 Satyakama Jabala and Sevā………………… 14 4. Fire teaches Upakosala…………….………… 15 Chāndogya 5. Svetaketu: five questions……………………. 18 and 6. Svetaketu: nature of sleep…………………... 22 7. That thou art, O Svetaketu………………….…23 Brihadāranyaka 8. Indra and virochana……………………….….. 29 Commentary…………………………...……..... 31 Upanishads End of Commenrary……………………....….. 55 Two large and difficult Upanishads are presented 2. Brihadāranyaka Upanishad …….…56 (without original Sanskrit verses) in simple modern English for those advanced students who have 9. Dialogue: Ajtsatru-Gargya……………...…. 61 read Bhagavad-Gita and other 9 Principal 10. Yajnavalkya and maitreyi ……………....…..63 Upanishads. Simpler important verses are 11. Meditation taught through horse’s head.. 65 12. Yajnavalkya: The best Vedic Scholar…… 66 printed in underlined-bold; comm- 13. Three ‘Da’ …………………………….…….…78 entaries from translators, references&Glossary. Commentary…………………………….……... 84 14. Each soul is dear to the other………...……90 By 15. The Wisdom of the Wise (Yagnavalkya)… 91 16. Gargi and the Imperishable ……………..…94 Swami Swahananda 17. Janaka and Yajnavalkya 1 ……………..…..95 and 18. Janaka and Yajnavalkya 2 …………..……..97 Swami Madhavananda et al. 19. The Process of Reincarnation…… …..… 100 Editor: Ramananda Prasad End of Commenrary …………….…..……….105 A Brief Sanskrit Glossary On page 844 of 908 of the pdf: www.gita-society.com/108Upanishads.pdf INTERNATIONAL GITA ***** Editor’s note: Most of the materials in this book are SOCIETY taken from the above webpage which does not have a Copyright mark. -

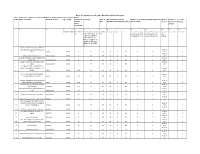

Bpc(Maharashtra) (Times of India).Xlsx

Notice for appointment of Regular / Rural Retail Outlet Dealerships BPCL proposes to appoint Retail Outlet dealers in Maharashtra as per following details : Sl. No Name of location Revenue District Type of RO Estimated Category Type of Minimum Dimension (in Finance to be arranged by the applicant Mode of Fixed Fee / Security monthly Site* M.)/Area of the site (in Sq. M.). * (Rs in Lakhs) Selection Minimum Bid Deposit Sales amount Potential # 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9a 9b 10 11 12 Regular / Rural MS+HSD in SC/ SC CC1/ SC CC- CC/DC/C Frontage Depth Area Estimated working Estimated fund required Draw of Rs in Lakhs Rs in Lakhs Kls 2/ SC PH/ ST/ ST CC- FS capital requirement for development of Lots / 1/ ST CC-2/ ST PH/ for operation of RO infrastructure at RO Bidding OBC/ OBC CC-1/ OBC CC-2/ OBC PH/ OPEN/ OPEN CC-1/ OPEN CC-2/ OPEN PH From Aastha Hospital to Jalna APMC on New Mondha road, within Municipal Draw of 1 Limits JALNA RURAL 33 ST CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 Draw of 2 VIllage jamgaon taluka parner AHMEDNAGAR RURAL 25 ST CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 VILLAGE KOMBHALI,TALUKA KARJAT(NOT Draw of 3 ON NH/SH) AHMEDNAGAR RURAL 25 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 Village Ambhai, Tal - Sillod Other than Draw of 4 NH/SH AURANGABAD RURAL 25 ST CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 ON MAHALUNGE - NANDE ROAD, MAHALUNGE GRAM PANCHYAT, TAL: Draw of 5 MULSHI PUNE RURAL 300 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 ON 1.1 NEW DP ROAD (30 M WIDE), Draw of 6 VILLAGE: DEHU, TAL: HAVELI PUNE RURAL 140 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 VILLAGE- RAJEGAON, TALUKA: DAUND Draw of 7 ON BHIGWAN-MALTHAN -

Devi: the Great Goddess (Smithsonian Institute)

Devi: The Great Goddess Detail of "Bhadrakali Appears to Rishi Chyavana." Folio 59 from the Tantric Devi series. India, Punjab Hills, Basohli, ca 1660-70. Opaque watercolor, gold, silver, and beetle-wing cases on paper. Purchase, Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution F1997.8 Welcome to Devi: The Great Goddess. This web site has been developed in conjunction with the exhibition of the same name. The exhibition is on view at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery from March 29, 1999 through September 6, 1999. Like the exhibition, this web site looks at the six aspects of the Indian goddess Devi. The site offers additional information on the contemporary and historical worship of Devi, activities for children and families, and a list of resources on South Asian arts and cultures. You may also want to view another Sackler web site: Puja: Expressions of Hindu Devotion, an on-line guide for educators explores Hindu worship and provides lesson plans and activities for children. This exhibition is made possible by generous grants from Enron/Enron Oil & Gas International, the Rockefeller Foundation, The Starr Foundation, Hughes Network Systems, and the ILA Foundation, Chicago. Related programs are made possible by Victoria P. and Roger W. Sant, the Smithsonian Educational Outreach Fund, and the Hazen Polsky Foundation. http://www.asia.si.edu/devi/index.htm (1 of 2) [7/1/2000 10:06:15 AM] Devi: The Great Goddess | Devi Homepage | Text Only | | Who is Devi | Aspects of Devi | Interpreting Devi | Tantric Devi | For Kids | Resources | | Sackler Homepage | Acknowledgements | The Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560. -

Part I the Religions of Indian Origin

Part I The Religions of Indian Origin MRC01 13 6/4/04, 10:46 AM Religions of Indian Origin AFGHANISTAN CHINA Amritsar Kedamath Rishikesh PAKISTAN Badrinath Harappa Hardwar Delhi Indus R. NEPAL Indus Civilization BHUTAN Mohenjo-daro Ayodhya Mathura Lucknow Ganges R. Pushkar Prayag BANGLADESH Benares Gaya Ambaji I N D I A Dakshineshwar Sidphur Bhopal Ahmadabad Jabalpur Jamshedpur Calcutta Dwarka Dakor Pavagadh Raipur Gimar Kadod Nagpur Bhubaneswar Nasik-Tryambak Jagannath Puri Bombay Hyderabad Vishakhapatnam Arabian Sea Panaji Bay of Bengal Tirupati Tiruvannamalai-Kaiahasti Bangalore Madras Mangalore Kanchipuram Pondicherry Calicut Kavaratti Island Madurai Thanjavar Hindu place of pilgrimage Rameswaram Pilgrimage route Major city SRI LANKA The Hindu cultural region 14 MRC01 14 6/4/04, 10:46 AM 1 Hinduism Hinduism The Spirit of Hinduism Through prolonged austerities and devotional practices the sage Narada won the grace of the god Vishnu. The god appeared before him in his hermitage and granted him the fulfillment of a wish. “Show me the magic power of your Maya,” Narada prayed. The god replied, “I will. Come with me,” but with an ambiguous smile on his lips. From the shade of the hermit grove, Vishnu led Narada across a bare stretch of land which blazed like metal under the scorching sun. The two were soon very thirsty. At some distance, in the glaring light, they perceived the thatched roofs of a tiny village. Vishnu asked, “Will you go over there and fetch me some water?” “Certainly, O Lord,” the saint replied, and he made off to the distant group of huts. When Narada reached the hamlet, he knocked at the first door. -

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings & Speeches Vol. 4

Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar (14th April 1891 - 6th December 1956) BLANK DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR WRITINGS AND SPEECHES VOL. 4 Compiled by VASANT MOON Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar : Writings and Speeches Vol. 4 First Edition by Education Department, Govt. of Maharashtra : October 1987 Re-printed by Dr. Ambedkar Foundation : January, 2014 ISBN (Set) : 978-93-5109-064-9 Courtesy : Monogram used on the Cover page is taken from Babasaheb Dr. Ambedkar’s Letterhead. © Secretary Education Department Government of Maharashtra Price : One Set of 1 to 17 Volumes (20 Books) : Rs. 3000/- Publisher: Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India 15, Janpath, New Delhi - 110 001 Phone : 011-23357625, 23320571, 23320589 Fax : 011-23320582 Website : www.ambedkarfoundation.nic.in The Education Department Government of Maharashtra, Bombay-400032 for Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Source Material Publication Committee Printer M/s. Tan Prints India Pvt. Ltd., N. H. 10, Village-Rohad, Distt. Jhajjar, Haryana Minister for Social Justice and Empowerment & Chairperson, Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Kumari Selja MESSAGE Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the Chief Architect of Indian Constitution was a scholar par excellence, a philosopher, a visionary, an emancipator and a true nationalist. He led a number of social movements to secure human rights to the oppressed and depressed sections of the society. He stands as a symbol of struggle for social justice. The Government of Maharashtra has done a highly commendable work of publication of volumes of unpublished works of Dr. Ambedkar, which have brought out his ideology and philosophy before the Nation and the world. In pursuance of the recommendations of the Centenary Celebrations Committee of Dr. -

CONCEIVING the GODDESS an Old Woman Drawing a Picture of Durga-Mahishasuramardini on a Village Wall, Gujrat State, India

CONCEIVING THE GODDESS An old woman drawing a picture of Durga-Mahishasuramardini on a village wall, Gujrat State, India. Photo courtesy Jyoti Bhatt, Vadodara, India. CONCEIVING THE GODDESS TRANSFORMATION AND APPROPRIATION IN INDIC RELIGIONS Edited by Jayant Bhalchandra Bapat and Ian Mabbett Conceiving the Goddess: Transformation and Appropriation in Indic Religions © Copyright 2017 Copyright of this collection in its entirety belongs to the editors, Jayant Bhalchandra Bapat and Ian Mabbett. Copyright of the individual chapters belongs to the respective authors. All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher. Monash University Publishing Matheson Library and Information Services Building, 40 Exhibition Walk Monash University Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia www.publishing.monash.edu Monash University Publishing brings to the world publications which advance the best traditions of humane and enlightened thought. Monash University Publishing titles pass through a rigorous process of independent peer review. www.publishing.monash.edu/books/cg-9781925377309.html Design: Les Thomas. Cover image: The Goddess Sonjai at Wai, Maharashtra State, India. Photograph: Jayant Bhalchandra Bapat. ISBN: 9781925377309 (paperback) ISBN: 9781925377316 (PDF) ISBN: 9781925377606 (ePub) The Monash Asia Series Conceiving the Goddess: Transformation and Appropriation in Indic Religions is published as part of the Monash Asia Series. The Monash Asia Series comprises works that make a significant contribution to our understanding of one or more Asian nations or regions. The individual works that make up this multi-disciplinary series are selected on the basis of their contemporary relevance.