The War Against Iraq in Transnational Broadcasting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CNN Communications Press Contacts Press

CNN Communications Press Contacts Allison Gollust, EVP, & Chief Marketing Officer, CNN Worldwide [email protected] ___________________________________ CNN/U.S. Communications Barbara Levin, Vice President ([email protected]; @ blevinCNN) CNN Digital Worldwide, Great Big Story & Beme News Communications Matt Dornic, Vice President ([email protected], @mdornic) HLN Communications Alison Rudnick, Vice President ([email protected], @arudnickHLN) ___________________________________ Press Representatives (alphabetical order): Heather Brown, Senior Press Manager ([email protected], @hlaurenbrown) CNN Original Series: The History of Comedy, United Shades of America with W. Kamau Bell, This is Life with Lisa Ling, The Nineties, Declassified: Untold Stories of American Spies, Finding Jesus, The Radical Story of Patty Hearst Blair Cofield, Publicist ([email protected], @ blaircofield) CNN Newsroom with Fredricka Whitfield New Day Weekend with Christi Paul and Victor Blackwell Smerconish CNN Newsroom Weekend with Ana Cabrera CNN Atlanta, Miami and Dallas Bureaus and correspondents Breaking News Lauren Cone, Senior Press Manager ([email protected], @lconeCNN) CNN International programming and anchors CNNI correspondents CNN Newsroom with Isha Sesay and John Vause Richard Quest Jennifer Dargan, Director ([email protected]) CNN Films and CNN Films Presents Fareed Zakaria GPS Pam Gomez, Manager ([email protected], @pamelamgomez) Erin Burnett Outfront CNN Newsroom with Brooke Baldwin Poppy -

The Shortlist

The shortlist Children's factual programme or series television Mint Pictures for Australian Children's TV Bushwhacked! (Series 2) Foundation Deadly Pole to Pole BBC Natural History Unit Jawla 2014 Al Jazeera Children's Channel Made in SA South African Broadcasting Corporation Matanglawin: Worst Case Scenario Weather ABS-CBN Corporation Pay it Forward Observator, Antena 1 The Joy of Life (Vom Glück des Lebens) Westdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR) Factual online production Cronulla Riots-The Day that shocked a Nation SBS Television (Australia) Days of Rage Digital Initiative Channel NewsAsia Mediacorp Pte Ltd IRANORAMA Webdoc.FR/France 24 Sochi:Outside the Arena Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty [RFE/RL] Webdocumentary: Serengeti-Toward an Uncertain Future DW Deutsche Welle Zaatari Refugee Camp CNN Live sports coverage television Aviva Premiership Rugby Final 2014 Sunset+Vine Istaf Superseries Finals 2013/2014 Astro Arena SDN BHD The Grand National IMG Productions for Channel 4 Television Domestic current affairs documentary television Dispatches:Breadline Kids Channel 4 Television Failon Today:Deluge ABS-CBN Corporation John F Kennedy a Legacy Remembered Voice of America Spotlight:Guns and Government BBC Suidlanders- Preparing for a Revolution E Sat Pty Ltd The Way they Steel Antena 3 International current affairs documentary television Difficult Destinations: Turkmenistan deMENSEN Dispatches: Children on the Frontline Channel 4 Television Our World: Yemen-World's most dangerous Journey (for BBC World News, The BBC News Channel and BBC One) BBC -

Study Suggests Racial Bias in Calls by NBA Referees 4 NBA, Some Players

Report: Study suggests racial bias in calls by NBA referees 4 NBA, some players dismiss study on racial bias in officiating 6 SUBCONSCIOUS RACISM DO NBA REFEREES HAVE RACIAL BIAS? 8 Study suggests referee bias ; NOTEBOOK 10 NBA, some players dismiss study that on racial bias in officiating 11 BASKETBALL ; STUDY SUGGESTS REFEREE BIAS 13 Race and NBA referees: The numbers are clearly interesting, but not clear 15 Racial bias claimed in report on NBA refs 17 Study of N.B.A. Sees Racial Bias In Calling Fouls 19 NBA, some players dismiss study that on racial bias in officiating 23 NBA calling foul over study of refs; Research finds white refs assess more penalties against blacks, and black officials hand out more to... 25 NBA, Some Players Dismiss Referee Study 27 Racial Bias? Players Don't See It 29 Doing a Number on NBA Refs 30 Sam Donnellon; Are NBA refs whistling Dixie? 32 Stephen A. Smith; Biased refs? Let's discuss something serious instead 34 4.5% 36 Study suggests bias by referees NBA 38 NBA, some players dismiss study on racial bias in officiating 40 Position on foul calls is offline 42 Race affects calls by refs 45 Players counter study, say refs are not biased 46 Albany Times Union, N.Y. Brian Ettkin column 48 The Philadelphia Inquirer Stephen A. Smith column 50 AN OH-SO-TECHNICAL FOUL 52 Study on NBA refs off the mark 53 NBA is crying foul 55 Racial bias? Not by refs, players say 57 CALL BIAS NOT HARD TO BELIEVE 58 NBA, players dismiss study on racial bias 60 NBA, players dismiss study on referee racial bias 61 Players dismiss -

Richard Quest

RICHARD QUEST CNN International Anchor Richard Quest is CNN’s foremost international business correspondent and presenter of Quest Means Business, the definitive word on how we earn and spend our money. Based in New York, he is one of the most instantly recognizable members of the CNN team. Quest Means Business destroys the myth that business is boring, bridging the gap between hard economics and entertaining television. CEOs and global finance ministers make a point of appearing on Quest Means Business. Guests of the show have included world leaders such as David Cameron and Petr Necas of the Czech Republic; the biggest names in banking such as Jamie Dimon of JP Morgan Chase Topics and Robert Zoellick, the former President of the World Bank; European policy makers including IMF boss Christine Lagarde, EC President Jose Manuel Barroso, Communications and former IMF chief Dominique Strauss-Kahn; and some of the most influential names in corporate America including DreamWorks CEO Jeffrey Katzenberg and former Ford CEO Alan Mulally. Quest’s dynamic and distinctive style has made him a unique figure in the field of business broadcasting. He has regularly reported from the G20 meetings and attends the World Economic Forum in Davos Switzerland each year. He has covered every major stock market and financial crisis since Black Monday in 1987 and has reported from key financial centres globally including Wall Street, London, Sao Paulo, Tokyo and Hong Kong. He is also the established airline and aviation correspondent at CNN. He has interviewed all of the major airline executives including Delta CEO Richard Anderson, Qatar Airways CEO Akbar Al Baker, AirAsia CEO Tony Fernandes and Emirates CEO Tim Clark. -

The Interviews

Jeff Schechtman Interviews December 1995 to April 2017 2017 Marcus du Soutay 4/10/17 Mark Zupan Inside Job: How Government Insiders Subvert the Public Interest 4/6/17 Johnathan Letham More Alive and Less Lonely: On Books and Writers 4/6/17 Ali Almossawi Bad Choices: How Algorithms Can Help You Think Smarter and Live Happier 4/5/17 Steven Vladick Prof. of Law at UT Austin 3/31/17 Nick Middleton An Atals of Countries that Don’t Exist 3/30/16 Hope Jahren Lab Girl 3/28/17 Mary Otto Theeth: The Story of Beauty, Inequality and the Struggle for Oral Health 3/28/17 Lawrence Weschler Waves Passing in the Night: Walter Murch in the Land of the Astrophysicists 3/28/17 Mark Olshaker Deadliest Enemy: Our War Against Killer Germs 3/24/17 Geoffrey Stone Sex and Constitution 3/24/17 Bill Hayes Insomniac City: New York, Oliver and Me 3/21/17 Basharat Peer A Question of Order: India, Turkey and the Return of the Strongmen 3/21/17 Cass Sunstein #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media 3/17/17 Glenn Frankel High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist and the Making of an American Classic 3/15/17 Sloman & Fernbach The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Think Alone 3/15/17 Subir Chowdhury The Difference: When Good Enough Isn’t Enough 3/14/17 Peter Moskowitz How To Kill A City: Gentrification, Inequality and the Fight for the Neighborhood 3/14/17 Bruce Cannon Gibney A Generation of Sociopaths: How the Baby Boomers Betrayed America 3/10/17 Pam Jenoff The Orphan's Tale: A Novel 3/10/17 L.A. -

RICHARD QUEST CNN International Anchor & TV Personality of the Year

RICHARD QUEST CNN International Anchor & TV Personality of the Year Quest Means Business, which airs weekdays on CNN authority on making the most of doing business on the International, destroys the myth that business is boring, road - moving from A to B on company time. As a bridging the gap between hard economics and business travel specialist, Quest has become a voice of entertaining television. CEOs and global nance authority on subjects like the launch of the Airbus ministers make a point of appearing on QMB. Guests of A380. In 2012 Quest covered the US Election campaign the show have included world leaders such as David with his own series, American Quest, in which he Cameron and Petr Necas of the Czech Republic; the travelled across the country interviewing a diverse biggest names in banking such as Jamie Dimon of JP range of voters. Quest is also the face of CNN’s Morgan Chase and Robert Zoellick, the former coverage of major UK events. In 2012 he guided an President of the World Bank; European policy makers international audience through the Queen’s Diamond including IMF boss Christine Lagarde, EC President Jose Jubilee celebrations live from the banks of the River Manuel Barroso, and former IMF chief Dominique Thames and used his expert knowledge of the British Strauss-Kahn; and some of the most inuential names Royal Family to front the channel’s coverage of the in corporate America including DreamWorks CEO 2011 marriage of Prince William and Kate Middleton, Jerey Katzenberg and Ford CEO Alan Mulally. now the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge. -

NOMINEES for the 31St ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED by the NATIONAL ACADEMY of TELEVISION ARTS &

NOMINEES FOR THE 31st ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY ® AWARDS ANNOUNCED BY THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES Winners to be announced on September 27th at Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center Frederick Wiseman to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award New York, N.Y. – July 15, 2010 – Nominations for the 31st Annual News and Documentary Emmy ® Awards were announced today by the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS). The News & Documentary Emmy ® Awards will be presented on Monday, September 27 at a ceremony at Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center, located in the Time Warner Center in New York City. The event will be attended by more than 1,000 television and news media industry executives, news and documentary producers and journalists. Emmy ® Awards will be presented in 41 categories, including Breaking News, Investigative Reporting, Outstanding Interview, and Best Documentary, among others. “From the ongoing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, to the struggling American economy, to the inauguration of Barack Obama, 2009 was a significant year for major news stories,” said Bill Small, Chairman of the News & Documentary Emmy ® Awards. “The journalists and documentary filmmakers nominated this year have educated viewers in understanding some of the most compelling issues of our time, and we salute them for their efforts.” This year’s prestigious Lifetime Achievement Award will be given to Frederick Wiseman, one of the most accomplished documentarians in the history of the medium. In a career spanning almost half a century, Wiseman has produced, directed and edited 38 films. His documentaries comprise a chronicle of American life unmatched by perhaps any other filmmaker. -

31St Annual News & Documentary Emmy Awards

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES 31st Annual News & Documentary EMMY AWARDS CONGRATULATES THIS YEAR’S NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® NOMINEES AND HONOREES WEEKDAYS 7/6 c CONGRATULATES OUR NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® NOMINEES Outstanding Continuing Coverage of a News Story in a Regularly Scheduled Newscast “Inside Mexico’s Drug Wars” reported by Matthew Price “Pakistan’s War” reported by Orla Guerin WEEKDAYS 7/6 c 31st ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY ® AWARDS LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT / FREDERICK WISEMAN CHAIRMAN’S AWARD / PBS NEWSHOUR EMMY®AWARDS PRESENTED IN 39 CATEGORIES NOMINEES NBC News salutes our colleagues for the outstanding work that earned 22 Emmy Nominations st NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION CUSTOM 5 ARTS & SCIENCES / ANNUAL NEWS & SUPPLEMENT 31 DOCUMENTARY / EMMY AWARDS / NEWSPRO 31st Annual News & Documentary Letter From the Chairman Emmy®Awards Tonight is very special for all of us, but especially so for our honorees. NATAS Presented September 27, 2010 New York City is proud to honor “PBS NewsHour” as the recipient of the 2010 Chairman’s Award for Excellence in Broadcast Journalism. Thirty-five years ago, Robert MacNeil launched a nightly half -hour broadcast devoted to national and CONTENTS international news on WNET in New York. Shortly thereafter, Jim Lehrer S5 Letter from the Chairman joined the show and it quickly became a national PBS offering. Tonight we salute its illustrious history. Accepting the Chairman’s Award are four S6 LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT dedicated and remarkable journalists: Robert MacNeil and Jim Lehrer; HONOREE - FREDERICK WISEMAN longtime executive producer Les Crystal, who oversaw the transition of the show to an hourlong newscast; and the current executive producer, Linda Winslow, a veteran of the S7 Un Certain Regard By Marie-Christine de Navacelle “NewsHour” from its earliest days. -

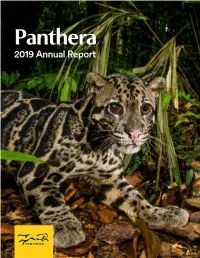

2019 Annual Report Panthera’S Mission Is to Ensure a Future for Wild Cats and the Vast Landscapes on Which They Depend

Panthera 2019 Annual Report Panthera’s mission is to ensure a future for wild cats and the vast landscapes on which they depend. Panthera Our vision is a world where wild cats thrive in healthy, natural and developed landscapes that sustain people and biodiversity. Contents 04 08 12 14 Nature Bats Last Cores and Conservation Program by Thomas S. Kaplan, Ph.D. Corridors in a Global Highlights Community 34 36 38 40 CLOUDIE ON CAMERA The Arabian A Corridor Searching for Conservation “I am particularly fond of this photograph of a clouded leopard Leopard to the World New Frontiers Science and because of the high likelihood that I wouldn’t capture it. After a leech and mosquito-filled five-day jungle trek, the biologists Initiatives Technology and I arrived at a ranger station at the top of the mountain in Highlights Malaysian Borneo, close to where this camera trap was located. I checked it but saw the battery was on its last leg. I decided to take the grueling full day’s hike back and forth to pick up a fresh battery. When I checked it the following afternoon, this young adult had come through just hours before. The physical 43 44 46 49 exhaustion was totally worth getting this amazing photograph.” 2019 Financial Board, Staff and Conservation After the Fires - Sebastian Kennerknecht, Panthera Partner Photographer Summary Science Council Council by Esteban Payán, Ph.D. 2 — 2019 ANNUAL REPORT A leopard in the Okavango Delta, Botswana Nature Bats Last The power of nature is an awesome thing to contemplate. the Jaguar Corridor. -

NOMINEES for the 40Th ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY ® AWARDS ANNOUNCED NBC's Andrea Mitchell to Be Honored with Lifetime

NOMINEES FOR THE 40th ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED NBC’s Andrea Mitchell to be honored with Lifetime Achievement Award September 24th Award Presentation at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall in NYC New York, N.Y. – July 25, 2019 (revised 10.18.19) – Nominations for the 40th Annual News and Documentary Emmy® Awards were announced today by The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS). The News & Documentary Emmy Awards will be presented on Tuesday, September 24th, 2019, at a ceremony at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall in New York City. The event will be attended by more than 1,000 television and news media industry executives, news and documentary producers and journalists. “The clear, transparent, and factual reporting provided by these journalists and documentarians is paramount to keeping our nation and its citizens informed,” said Adam Sharp, President & CEO, NATAS. “Even while under attack, truth and the hard-fought pursuit of it must remain cherished, honored, and defended. These talented nominees represent true excellence in this mission and in our industry." In addition to celebrating this year’s nominees in forty-nine categories, the National Academy is proud to honor Andrea Mitchell, NBC News’ chief foreign affairs correspondent and host of MSNBC's “Andrea Mitchell Reports," with the Academy’s Lifetime Achievement Award for her groundbreaking 50-year career covering domestic and international affairs. The 40th Annual News & Documentary Emmy® Awards honors programming distributed during the calendar -

Renowned CNN Anchor Richard Quest on the Tough Balancing Act Between Work — That He Says Is Also Fun — and Life. P4-5

Community Community Indian Rowad Ehlela Cultural talks about P6Center P16 his life and (ICC) organises a overcoming farewell get- challenges together for a long with a positive time staff . mindset. Sunday, August 5, 2018 Dhul-Qa’da 23, 1439 AH Doha today: 340 - 420 QQuestuest Renowned CNN anchor Richard Quest on the tough balancing act between work — that he says is also fun — and life. P4-5 COVER STORY 2 GULF TIMES Sunday, August 5, 2018 COMMUNITY ROUND & ABOUT Patrick DIRECTION: Mandie Fletcher CAST: Beattie Edmondson, Ed Skreik, Emily Atack, Jennifer Saunders SYNOPSIS: This comedy fi lm is about a young woman named Sarah, whose life changes when her grandmother gives her prized possession, a spoilt Pug named Patrick. Sarah is a young woman whose life PRAYER TIME is in a bit of a mess. The last thing she needs is someone Fajr 3.39am else to look after. Sarah and Shorooq (sunrise) 5.03am Patrick are ‘a match made Zuhr (noon) 11.40am in hell’. He eats bedroom Asr (afternoon) 3.08pm slippers, destroys furniture Maghreb (sunset) 6.19pm and turns up his nose at Isha (night) 7.49pm regular dog food. She moans and struggles with the duties of fur-motherhood. USEFUL NUMBERS THEATRES: The Mall, Landmark, Royal Plaza Emergency 999 Worldwide Emergency Number 112 Kahramaa – Electricity and Water 991 Local Directory 180 International Calls Enquires 150 Hamad International Airport 40106666 Labor Department 44508111, 44406537 Mowasalat Taxi 44588888 Qatar Airways 44496000 Hamad Medical Corporation 44392222, 44393333 Qatar General Electricity and Water Corporation 44845555, 44845464 Primary Health Care Corporation 44593333 44593363 Qatar Assistive Technology Centre 44594050 Qatar News Agency 44450205 44450333 Q-Post – General Postal Corporation 44464444 Humanitarian Services Offi ce (Single window facility for the repatriation of bodies) Ministry of Interior 40253371, 40253372, 40253369 Ministry of Health 40253370, 40253364 Hamad Medical Corporation 40253368, 40253365 Leo Da Vince: Mission Monalisa some experience in inventing advanced give all the money he debts. -

World Economic Forum Annual Meeting

World Economic Forum Annual Meeting List of Participants As of 30 April 2013 Davos-Klosters, Switzerland, 23-27 January 2013 Ivonne A-Baki Minister for the Yasuní-ITT Initiative of Ecuador Svein Aaser Chairman of the Board Telenor ASA Norway Florencio B. Abad Secretary of Budget and Management of the Philippines Mhammed Abbad Founder Al Jisr Morocco Andaloussi Faisal J. Abbas Editor-in-Chief Al Arabiya News Channel, United Arab Emirates English Service Ali Abbasov Minister of Communication and Information Technologies of Azerbaijan Mustafa Partner and Chairman of the Executive The Abraaj Group United Arab Emirates Abdel-Wadood Committee Mohd Razali Abdul Chairman Peremba Group of Companies Malaysia Rahman Khalid Honorary Chairman Vision 3 United Arab Emirates Abdulla-Janahi Abdullah II Ibn Al King of the Hashemite Kingdom of Hussein Jordan Rovnag Abdullayev President SOCAR (State Oil Company Azerbaijan of the Azerbaijan Republic) Shinzo Abe Prime Minister of Japan Derek Aberle Executive Vice-President, Qualcomm Qualcomm USA Incorporated and Group President Asanga Executive Director Lakshman Kadirgamar Sri Lanka Abeyagoonasekera Institute for International Relations and Strategic Studies Reuben Abraham Executive Director, Centre for Emerging Indian School of Business India Markets Solutions Magid Abraham Co-Founder, President and Chief comScore Inc. USA Executive Officer Issa Abdul Salam Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Salam International Qatar Abu Issa Investment Ltd Aclan Acar Chairman of the Board of Directors Dogus Otomotiv AS