©2016 Jennifer Lynn Pettit ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Happy 20Th Birthday Spycher by Diane White in September 2019, the Delightful Celebra- Tion for Spycher Highlighted the DREAM, DARE, DO & DEVELOP Theme

Chalet ChatterIssue 20 — Winter/Spring 2019-2020 Happy 20th Birthday Spycher by Diane White In September 2019, the delightful celebra- tion for Spycher highlighted the DREAM, DARE, DO & DEVELOP theme. Thanks to the coordinated efforts of Marjolein Zoll-Schriek on behalf of the Foundation and Swiss Friends. Charlotte Christ-Weber and Peira Fleiner founding Swiss members of the Foundation, former Guiders-in-Charge Inge Lyck and Katharina Kalcsics, Our Chalet’s historian Ann Mitchell, Katherine Duncan-Brown, and many THE SPYCHER at Our Chalet. others were in attendance. Delicious sweet treats, a special cake and sandwiches on a The DEVELOP is an ongoing process. Today braided bread loaf, along with tea and coffee, the Spycher welcomes all. On the first floor, the juice and hot chocolate, were enjoyed. A warm front area is reception, the shop and the man- and special thank you to Tanya Tulloch, World ager’s small office. Program and operation of- Centre Manager, and her staff for making all fices are located down the hall and in the Ann our dreams come true. Bodsen Room. On the second level are seven The DREAM for a new building began in the bedrooms, with 18 beds and three full bath- 1980s when the need for more beds, office rooms which are handicapped-accessible by a space, handicapped accessibility, and a confer- motorized lift. Each bedroom is named for one ence room was explored. Our Chalet’s program of the local mountains. The third level, the at- events highlighted the beginning of the Helen tic, accommodates eight beds and has a half- Storrow Seminars in 1986. -

Hclassifi Cation

Form No 10-300 (Rev 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FOR NPS USE ONLY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RECEIVED INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ___________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS_____ [NAME HISTORIC HOOVER HOUSE AND/OR COMMON ________Lou Henry Hoover House __ ____________________________ LOCATION STREET& NUMBER 623 Mirada Road Leland Stanford, Jr. University _NOTFOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Palo Alto _ VICINITY OF Twelfth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE California 06 Santa Clara 085 HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^-OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH _WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL ^PRIVATE RESIDENCE _SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS 3LYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER (OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Leland Stanford, Jr. University STREET & NUMBER Attn: Donald Carlson, University Relations CITY. TOWN STATE Stanford VICINITY OF California 94305 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC County Recorder, County of Santa Clara STREET & NUMBER 70 West Redding Street CITY. TOWN STATE San Jose, Galifornia REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE National Register of Historic Places DATE January 30, 1978 iFEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS National Park Service CITY. TOWN STATE Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE X_ EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^.ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS ^.ALTERED _MOVED DATE_ _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Lou Henry Hoover house is located at 623 Mirada Road at the southwest corner of Leland Stanford, Jr. -

Hatfield Aerial Surveys Photographs

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt609nf5sn Online items available Guide to the Hatfield Aerial Surveys photographs Daniel Hartwig Stanford University. Libraries.Department of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford, California October 2010 Copyright © 2015 The Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved. Guide to the Hatfield Aerial PC0086 1 Surveys photographs Overview Call Number: PC0086 Creator: Hatfield Aerial Photographers Title: Hatfield Aerial Surveys photographs Dates: 1947-1979 Physical Description: 3 Linear feet (43 items) Summary: This collection consists of aerial photographs of the Stanford University campus and lands taken by Hatfield Aerial Surveys, a firmed owned by Adrian R. Hatfield. The images date from 1947 to 1979 and are of two sizes: 18 by 22 inches and 20 by 24 inches. Language(s): The materials are in English. Repository: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford, CA 94305-6064 Email: [email protected] Phone: (650) 725-1022 URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Information about Access Open for research. Scope and Contents note This collection consists of aerial photographs of the Stanford University campus and lands taken by Hatfield Aerial Surveys, a firmed owned by Adrian R. Hatfield. The images date from 1947 to 1979 and are of two sizes: 18 by 22 inches and 20 by 24 inches. Access Terms Hatfield Aerial Photographers Aerial Photographs Box 1 AP4 Stanford campus, from Faculty housing area before Shopping Center and Medical Center built; Old Roble still standing, Stern under construction; ca. 1947 Box 1 AP5 Main academic campus, ca. -

Architecture and Society in Edith Wharton's the Age of Innocence

"The Intolerable Ugliness of New York": Architecture and Society in Edith Wharton's The Age of Innocence Cynthia G. Falk Edith Wharton's novel The Age of Innocence was written in and about an era characterized in the United States by immense political, economic, and cul tural change, which led many Americans to reevaluate how they defined their country and themselves. As an expatriate, Wharton worked on the manuscript in France in the years just after World War I amidst ongoing debates about the Treaty of Versailles, wartime reparations, and the creation of the League of Nations. The work was received by the American public first in the summer of 1920, when it appeared in serial form in the magazine Pictorial Review, and again later that fall, when it was published as a novel. The story was set almost fifty years earlier in the New York and Newport, Rhode Island, of Wharton's youth. Through her descriptions of that earlier period's built environment and social conventions, Wharton drew conclusions about American society that car ried added weight in her own day. Wharton's assessment of architecture, inte rior design, and codes of conduct in late-nineteenth-century America distanced her from many of her American contemporaries by demonstrating her disillu sionment with her increasingly influential homeland. From the conclusion of the Civil War to the conclusion of World War I, Americans saw their country transformed. At the beginning of the period, the United States was still recovering from the destruction and division that resulted from sectional crisis. Violent conflicts with American Indians regularly threat- 0026-3079/2001/4202-019$2.50/0 American Studies, 42:2 (Summer 2001): 19-43 19 20 Cynthia G. -

Co-Operative Living at Stanford a Report of SWOPSI 146

CoopAtStan-28W Weds May 16 7:00 pm Draft Only — Draft Only — Draft Only Co-operative Living at Stanford A Report of SWOPSI 146 May 1990 Preface This report resulted from the hard work of the students of a Stanford Workshops on Political and Social Issues (SWOPSI) class called “Co-operative Living and the Current Crisis at Stanford.” Both instructors and students worked assiduously during Winter quarter 1990 researching and writing the various sections of this report. The success of the class’s actions at Stanford and of this report resulted from blending academics and activism (a fun but time-consuming combination). Contributing to this report were: Paul Baer (instructor) Chris Balz Natalie Beerer Tom Boellstorff Scott Braun Liz Cook Joanna Davidson (instructor) Yelena Ginzburg John Hagan Maggie Harrison Alan Haynie Madeline Larsen (instructor) Dave Nichols Sarah Otto Ethan Pride Eric Rose (instructor) Randy Schutt Eric Schwitzgebel Raquel Stote Jim Welch Michael Wooding Bruce Wooster ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people who contributed to this final report and the resolution of the Co-op crisis. Although we would like to mention everyone by name, it might double the length of this entire document. Our everlasting thanks go out to everyone who contributed. Especially Leland Stanford for having his co-operative vision, the SWOPSI Office for carrying it on and providing the opportunity for this class to happen, Henry Levin, our faculty sponsor for his help with the proposal process, Lee Altenberg, whose tremendous knowledge of Stanford co-operative lore is exceeded only by his boundless passion for the co-ops themselves; the Co-op Alumni network, the folks at the Davis, Berkeley, and Cornell co-ops, NASCO, and all of the existing Stanford co-ops for their support during this entire process. -

Collected Stories 1911-1937 Ebook, Epub

COLLECTED STORIES 1911-1937 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Edith Wharton | 848 pages | 16 Oct 2014 | The Library of America | 9781883011949 | English | New York, United States Collected Stories 1911-1937 PDF Book In "The Mission of Jane" about a remarkable adopted child and "The Pelican" about an itinerant lecturer , she discovers her gift for social and cultural satire. Sandra M. Marion Elizabeth Rodgers. Collected Stories, by Edith Wharton ,. Anson Warley is an ageing New York bachelor who once had high cultural aspirations, but he has left them behind to give himself up to the life of a socialite and dandy. Sort order. Michael Davitt Bell. A Historical Guide to Edith Wharton. With this two-volume set, The Library of America presents the finest of Wharton's achievement in short fiction: 67 stories drawn from the entire span of her writing life, including the novella-length works The Touchstone , Sanctuary , and Bunner Sisters , eight shorter pieces never collected by Wharton, and many stories long out-of-print. Anthony Trollope. The Edith Wharton Society Old but comprehensive collection of free eTexts of the major novels, stories, and travel writing, linking archives at University of Virginia and Washington State University. The Library of America series includes more than volumes to date, authoritative editions that average 1, pages in length, feature cloth covers, sewn bindings, and ribbon markers, and are printed on premium acid-free paper that will last for centuries. Elizabeth Spencer. Inspired by Your Browsing History. Books by Edith Wharton. Hill, Hamlin L. This work was followed several other novels set in New York. -

Noteworthy.Pdf

Deodar Cedar Cedrus deodara 7 Three deodar cedars at Burnham Pavilion, along Serra and Galvez streets, date to 1915; two are about 4 feet in diameter, the much-pruned double- trunk specimen is 5 feet across. Some of Stanford’s Noteworthy Trees Atlas Cedar Cedrus libani atlantica ‘Glauca’ 8 In the lawn in front of Hoover Tower, this tree was planted by President This list of noteworthy trees at Stanford is a compilation by the author and editors of this Benjamin Harrison during a campus visit in 1891. book, staff members of the Stanford Grounds Department, and other interested tree lovers. See the Tree List in Order of Botanical Names, beginning on page 32, for more information on Port Orford Cedar Chamaecyparis lawsoniana 9 each species. Map on inside back cover shows approximate locations of these trees. Several examples, new and old, of this graceful conifer can be seen at King- scote Gardens, including columnar forms near the pond, one with gold tips. 1 Santa Lucia Fir Abies bracteata In the grove on Serra Street, left of the entrance to Lou Henry Hoover Floss-Silk Tree Chorisia speciosa 10 Building. Planted before 1900, this is thought to be Stanford’s only speci- An interesting green-trunk tree with impressive spines and spectacular men of the rare, slow-growing tree. flowers, in the outer southwest island of the Quad. See the main text for other good examples. 2 Spanish Fir Abies pinsapo A superb full specimen partially obscures 634 Alvarado Row; it probably Monterey Cypress Cupressus macrocarpa 11 was planted around 1908, when the house was built. -

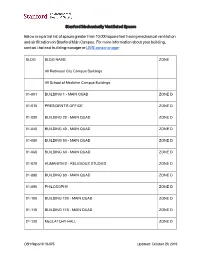

Mechanically-Ventilated-Spaces

Stanford Mechanically Ventilated Spaces Below is a partial list of spaces greater than 10,000 square feet having mechanical ventilation and air filtration on Stanford Main Campus. For more information about your building, contact the local building manager or LBRE zone manager: BLDG BLDG NAME ZONE All Redwood City Campus Buildings All School of Medicine Campus Buildings 01-001 BUILDING 1 - MAIN QUAD ZONE D 01-010 PRESIDENT'S OFFICE ZONE D 01-020 BUILDING 20 - MAIN QUAD ZONE D 01-040 BUILDING 40 - MAIN QUAD ZONE D 01-050 BUILDING 50 - MAIN QUAD ZONE D 01-060 BUILDING 60 - MAIN QUAD ZONE D 01-070 HUMANITIES - RELIGIOUS STUDIES ZONE D 01-080 BUILDING 80 - MAIN QUAD ZONE D 01-090 PHILOSOPHY ZONE D 01-100 BUILDING 100 - MAIN QUAD ZONE D 01-110 BUILDING 110 - MAIN QUAD ZONE D 01-120 McCLATCHY HALL ZONE D OSH Report# 19-075 Updated: October 29, 2019 01-160 WALLENBERG HALL ZONE D 01-170 BUILDING 170 - MAIN QUAD ZONE D 01-200 LANE HISTORY CORNER ZONE D 01-240 BUILDING 240 - MAIN QUAD ZONE D 01-250 BUILDING 250 - MAIN QUAD ZONE D 01-260 PIGOTT HALL (LANGUAGE CORNER) ZONE D 01-320 BRAUN CORNER (GEOLOGY CORNER) ZONE D 01-360 BUILDING 360 - MAIN QUAD ZONE D 01-370 BUILDING 370 - MAIN QUAD ZONE D 01-380 SLOAN MATHEMATICS CTR (MATH CORNER) ZONE D 01-420 JORDAN HALL (PSYCHOLOGY) ZONE D 01-460 MARGARET JACKS HALL ZONE D 01-500 MEMORIAL CHURCH ZONE D 02-010 BOOKSTORE ZONE C 02-020 CENTER FOR EDUCATIONAL RSCH (CERAS) ZONE C 02-040 NEUKOM BUILDING ZONE C 02-050 LAW SCHOOL - CROWN QUADRANGLE ZONE C OSH Report# 19-075 Updated: October 29, 2019 02-070 MUNGER GRADUATE RESIDENCE - J-SoH (Building 5) MARKET R&DE AND MAIN LOBBY 02-100 HUMANITIES CENTER ZONE C 02-140 KINGSCOTE GARDENS ZONE C 02-210 BRAUN MUSIC CENTER ZONE C 02-300 TRESIDDER MEMORIAL UNION ZONE C 02-350 FACULTY CLUB ZONE C 02-500 TERMAN ENGINEERING LABORATORY ZONE A 02-520 MECHANICAL ENGINEERING, TSG ZONE A 02-530 MECHANICAL ENGINEERING ADMIN. -

Wharton - Wikipedia

4/27/2020 Edith Wharton - Wikipedia Edith Wharton Edith Wharton (/ hw rtən/; born Edith Newbold Jones; January 24, 1862 – August 11, 1937) was an American Edith Wharton novelist, short story writer, playwright, and designer. Wharton drew upon her insider's knowledge of the upper class New York "aristocracy" to realistically portray the lives and morals of the Gilded Age. In 1921, she was the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Literature. She was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame in 1996.[1] Contents Biography Early life Early writing Socialite and debutante 1880s Travels and life abroad Edith Wharton, c. 1895 Later years Death Born Edith Newbold Writing Jones Career January 24, 1862 Themes in writings New York City Influences Died August 11, 1937 Works (aged 75) Novels Saint-Brice-sous- Novellas and novelette Forêt, France Poetry Short story collections Resting Cimetière des place Non-fiction Gonards As editor Occupation Novelist, short story Adaptations writer, designer. Film Notable Pulitzer Prize for Television awards Literature Theater 1921 The Age of In popular culture Innocence References Spouse Edward Robbins Citations Bibliography Wharton (1885– 1913) Further reading https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edith_Wharton 1/16 4/27/2020 Edith Wharton - Wikipedia External links Online editions Signature Biography Early life Edith Wharton was born Edith Newbold Jones on January 24, 1862 to George Frederic Jones and Lucretia Stevens Rhinelander at their brownstone at 14 West Twenty-third Street in New York City.[2][3] To her -

Stanford University (A): Indirect Cost Recovery

Graduate School of Business S-A-155A Stanford University July 1994 Stanford University (A): Indirect Cost Recovery March 13, 1991, Capitol Hill, Washington, D.C. “What we will hear today is a story of tax-payer dollars going to bloated overhead [rather] than to scientific research. It is a story of excess and arrogance, compounded by lax government oversight,” said John D. Dingell (D-Mich.), Chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations. Dingell concludes that three explanations are possible for events at Stanford University: “One is that there is great incompetence out there; one is that there is rascality out there; one is there may be both.” Less than a year earlier, the New York Times had praised Stanford for “slashing its budget 13 percent, laying off nonteaching employees and tearing up organiza- tional charts—all the while pledging not to raise tuition by more than 1 percentage point above the inflation rate.” The acting dean of Harvard University’s faculty of arts and sciences said, “These concerns are quite common. I admire Stanford for the fact that they have started to tackle this, and I am quite sure the rest of us will follow soon—not necessarily in terms of major cuts, but in terms of attempting to deal with these financial questions.”1 Background Stanford is at the center of a roiling dispute over the federal research dol- lars that vaulted the University to international prominence. In a statement to Copyright c 1991 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. -

Triennial Report World Conference Document #6A Covid-19 Pandemic

2018-2020 TRIENNIAL REPORT WORLD CONFERENCE DOCUMENT #6A COVID-19 PANDEMIC: WAGGGS RESPONSE TO COVID-19 COVID-19, and its global impact, became the all-encompassing focal point for 2020. For the girl, the pandemic created huge social, emotional, health and financial anxiety, and even now, we are still only beginning to understand its true scale. Girls, volunteers and leaders from around the Movement responded quickly. They came together to support communities, create essential equipment for frontline workers, deliver food and care packages for the elderly and the vulnerable, all the while remaining a collective beacon of light. The pandemic also drove Girl Guiding and Girl Scouting worldwide to pause in-person activities in its near entirety and, move, where possible to an online offering. It has put immense strain on our Members; as a Movement, we were not sufficiently web-ready, many Members do not have the financial and organisational resources needed to weather this period, and the financial uncertainty caused by the economic slowdown has in turn affected workforce and income sources. Like many of our Members, WAGGGS too as an Organisation has been deeply impacted by the pandemic. We took the decision in March 2020 to close all of our World Centres and, in April, we closed both the World Bureau in London and the Brussels office. Where available, we placed nearly half of our eligible staff into government-supported job protection programmes. We adapted our staff and organisational model to ensure that we could continue to meet the immediate -

Property and Identity in the Custom of the Country and Ultimately Meaning, on Personal Identity As Volatile Economic Conditions Erode Familiar Social Structures

Sassoubre 687 PROPERTY AND IDENTITY IN f THE CUSTOM OF THE COUNTRY Ticien Marie Sassoubre Critical responses to The Custom of the Country have been deeply influenced by events in Edith Wharton's life during the period over which the novel was written (1907–13). Connections between the novel and Wharton's financial success (resulting from her shrewd- ness in negotiation with publishers as well as her literary talent and productivity), her affair with Morton Fullerton, and the difficult deci- sion to divorce her husband of nearly thirty years are readily appar- ent. As a result, The Custom of the Country is consistently read as a novel about divorce, or a critique of the patriarchal oppression of women.1 In these readings, Undine Spragg, the novel's main figure, is conceived as a frustrated entrepreneur forced by her gender to pursue her business in the domestic sphere.2 The critical preoccupa- tion with the novel as a fictionalization of Wharton's personal experi- ences explains why those who have so frequently praised its fine prose and unflinching social observation have either exaggerated Undine's "success" or felt, with Percy Lubbock, that the novel lacks "a controlling and unifying center" (53). In this article, I argue that The Custom of the Country should be read as a novel about changing property relations and the ways in which those property relations are constitutive of personal identity. Reading the novel through this lens discloses its carefully constructed narrative structure and the- matic coherence—a coherence distorted by readings concerned pri- marily with its treatment of gender inequality or divorce.