Oceans of Archaea Abundant Oceanic Crenarchaeota Appear to Derive from Thermophilic Ancestors That Invaded Low-Temperature Marine Environments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anoxygenic Photosynthesis in Photolithotrophic Sulfur Bacteria and Their Role in Detoxication of Hydrogen Sulfide

antioxidants Review Anoxygenic Photosynthesis in Photolithotrophic Sulfur Bacteria and Their Role in Detoxication of Hydrogen Sulfide Ivan Kushkevych 1,* , Veronika Bosáková 1,2 , Monika Vítˇezová 1 and Simon K.-M. R. Rittmann 3,* 1 Department of Experimental Biology, Faculty of Science, Masaryk University, 62500 Brno, Czech Republic; [email protected] (V.B.); [email protected] (M.V.) 2 Department of Biology, Faculty of Medicine, Masaryk University, 62500 Brno, Czech Republic 3 Archaea Physiology & Biotechnology Group, Department of Functional and Evolutionary Ecology, Universität Wien, 1090 Vienna, Austria * Correspondence: [email protected] (I.K.); [email protected] (S.K.-M.R.R.); Tel.: +420-549-495-315 (I.K.); +431-427-776-513 (S.K.-M.R.R.) Abstract: Hydrogen sulfide is a toxic compound that can affect various groups of water microorgan- isms. Photolithotrophic sulfur bacteria including Chromatiaceae and Chlorobiaceae are able to convert inorganic substrate (hydrogen sulfide and carbon dioxide) into organic matter deriving energy from photosynthesis. This process takes place in the absence of molecular oxygen and is referred to as anoxygenic photosynthesis, in which exogenous electron donors are needed. These donors may be reduced sulfur compounds such as hydrogen sulfide. This paper deals with the description of this metabolic process, representatives of the above-mentioned families, and discusses the possibility using anoxygenic phototrophic microorganisms for the detoxification of toxic hydrogen sulfide. Moreover, their general characteristics, morphology, metabolism, and taxonomy are described as Citation: Kushkevych, I.; Bosáková, well as the conditions for isolation and cultivation of these microorganisms will be presented. V.; Vítˇezová,M.; Rittmann, S.K.-M.R. -

Limits of Life on Earth Some Archaea and Bacteria

Limits of life on Earth Thermophiles Temperatures up to ~55C are common, but T > 55C is Some archaea and bacteria (extremophiles) can live in associated usually with geothermal features (hot springs, environments that we would consider inhospitable to volcanic activity etc) life (heat, cold, acidity, high pressure etc) Thermophiles are organisms that can successfully live Distinguish between growth and survival: many organisms can survive intervals of harsh conditions but could not at high temperatures live permanently in such conditions (e.g. seeds, spores) Best studied extremophiles: may be relevant to the Interest: origin of life. Very hot environments tolerable for life do not seem to exist elsewhere in the Solar System • analogs for extraterrestrial environments • `extreme’ conditions may have been more common on the early Earth - origin of life? • some unusual environments (e.g. subterranean) are very widespread Extraterrestrial Life: Spring 2008 Extraterrestrial Life: Spring 2008 Grand Prismatic Spring, Yellowstone National Park Hydrothermal vents: high pressure in the deep ocean allows liquid water Colors on the edge of the at T >> 100C spring are caused by different colonies of thermophilic Vents emit superheated water (300C or cyanobacteria and algae more) that is rich in minerals Hottest water is lifeless, but `cooler’ ~50 species of such thermophiles - mostly archae with some margins support array of thermophiles: cyanobacteria and anaerobic photosynthetic bacteria oxidize sulphur, manganese, grow on methane + carbon monoxide etc… Sulfolobus: optimum T ~ 80C, minimum 60C, maximum 90C, also prefer a moderately acidic pH. Live by oxidizing sulfur Known examples can grow (i.e. multiply) at temperatures which is abundant near hot springs. -

Taurine Is a Major Carbon and Energy Source for Marine Prokaryotes in the North Atlantic Ocean Off the Iberian Peninsula

Microbial Ecology https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-019-01320-y MICROBIOLOGY OF AQUATIC SYSTEMS Taurine Is a Major Carbon and Energy Source for Marine Prokaryotes in the North Atlantic Ocean off the Iberian Peninsula Elisabeth L. Clifford1 & Marta M. Varela2 & Daniele De Corte3 & Antonio Bode2 & Victor Ortiz1 & Gerhard J. Herndl1,4 & Eva Sintes1,5 Received: 28 June 2018 /Accepted: 3 January 2019 # The Author(s) 2019 Abstract Taurine, an amino acid-like compound, acts as an osmostress protectant in many marine metazoans and algae and is released via various processes into the oceanic dissolved organic matter pool. Taurine transporters are widespread among members of the marine prokaryotic community, tentatively indicating that taurine might be an important substrate for prokaryotes in the ocean. In this study, we determined prokaryotic taurine assimilation and respiration throughout the water column along two transects in the North Atlantic off the Iberian Peninsula. Taurine assimilation efficiency decreased from the epipelagic waters from 55 ± 14% to 27 ± 20% in the bathypelagic layers (means of both transects). Members of the ubiquitous alphaproteobacterial SAR11 clade accounted for a large fraction of cells taking up taurine, especially in surface waters. Archaea (Thaumarchaeota + Euryarchaeota) were also able to take up taurine in the upper water column, but to a lower extent than Bacteria. The contribution of taurine assimilation to the heterotrophic prokaryotic carbon biomass production ranged from 21% in the epipelagic layer to 16% in the bathypelagic layer. Hence, we conclude that dissolved free taurine is a significant carbon and energy source for prokaryotes throughout the oceanic water column being utilized with similar efficiencies as dissolved free amino acids. -

Specificity Re-Evaluation of Oligonucleotide Probes for the Detection of Marine Picoplankton by Tyramide Signal Amplification-Fl

fmicb-08-00854 May 24, 2017 Time: 20:18 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 29 May 2017 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00854 Specificity Re-evaluation of Oligonucleotide Probes for the Detection of Marine Picoplankton by Tyramide Signal Amplification-Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization Virginie Riou, Marine Périot and Isabelle C. Biegala* Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Mediterranean Institute of Oceanography – Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, Aix Marseille Université – Université de Toulon, Marseille, France Edited by: Sophie Rabouille, Oligonucleotide probes are increasingly being used to characterize natural microbial Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), France assemblages by Tyramide Signal Amplification-Fluorescent in situ Hybridization (TSA- Reviewed by: FISH, or CAtalysed Reporter Deposition CARD-FISH). In view of the fast-growing rRNA Fernanda De Avila Abreu, databases, we re-evaluated the in silico specificity of eleven bacterial and eukaryotic Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil probes and competitor frequently used for the quantification of marine picoplankton. Tom Bibby, We performed tests on cell cultures to decrease the risk for non-specific hybridization, University of Southampton, before they are used on environmental samples. The probes were confronted to recent United Kingdom databases and hybridization conditions were tested against target strains matching *Correspondence: Isabelle C. Biegala perfectly with the probes, and against the closest non-target strains presenting one [email protected] -

Functional Equivalence and Evolutionary Convergence In

Functional equivalence and evolutionary convergence PNAS PLUS in complex communities of microbial sponge symbionts Lu Fana,b, David Reynoldsa,b, Michael Liua,b, Manuel Starkc,d, Staffan Kjelleberga,b,e, Nicole S. Websterf, and Torsten Thomasa,b,1 aSchool of Biotechnology and Biomolecular Sciences and bCentre for Marine Bio-Innovation, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales 2052, Australia; cInstitute of Molecular Life Sciences and dSwiss Institute of Bioinformatics, University of Zurich, 8057 Zurich, Switzerland; eSingapore Centre on Environmental Life Sciences Engineering, Nanyang Technological University, Republic of Singapore; and fAustralian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville, Queensland 4810, Australia Edited by W. Ford Doolittle, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada, and approved May 21, 2012 (received for review February 24, 2012) Microorganisms often form symbiotic relationships with eukar- ties (11, 12). Symbionts also can be transmitted vertically through yotes, and the complexity of these relationships can range from reproductive cells and larvae, as has been demonstrated in those with one single dominant symbiont to associations with sponges (13, 14), insects (15), ascidians (16), bivalves (17), and hundreds of symbiont species. Microbial symbionts occupying various other animals (18). Vertical transmission generally leads equivalent niches in different eukaryotic hosts may share func- to microbial communities with limited variation in taxonomy and tional aspects, and convergent genome evolution has been function among host individuals. reported for simple symbiont systems in insects. However, for Niches with similar selections may exist in phylogenetically complex symbiont communities, it is largely unknown how prev- divergent hosts that lead comparable lifestyles or have similar alent functional equivalence is and whether equivalent functions physiological properties. -

Genomic Analysis of Family UBA6911 (Group 18 Acidobacteria)

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.09.439258; this version posted April 10, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 2 Genomic analysis of family UBA6911 (Group 18 3 Acidobacteria) expands the metabolic capacities of the 4 phylum and highlights adaptations to terrestrial habitats. 5 6 Archana Yadav1, Jenna C. Borrelli1, Mostafa S. Elshahed1, and Noha H. Youssef1* 7 8 1Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, 9 OK 10 *Correspondence: Noha H. Youssef: [email protected] bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.09.439258; this version posted April 10, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 11 Abstract 12 Approaches for recovering and analyzing genomes belonging to novel, hitherto unexplored 13 bacterial lineages have provided invaluable insights into the metabolic capabilities and 14 ecological roles of yet-uncultured taxa. The phylum Acidobacteria is one of the most prevalent 15 and ecologically successful lineages on earth yet, currently, multiple lineages within this phylum 16 remain unexplored. Here, we utilize genomes recovered from Zodletone spring, an anaerobic 17 sulfide and sulfur-rich spring in southwestern Oklahoma, as well as from multiple disparate soil 18 and non-soil habitats, to examine the metabolic capabilities and ecological role of members of 19 the family UBA6911 (group18) Acidobacteria. -

Supplementary Materials: Patterns of Sponge Biodiversity in the Pilbara, Northwestern Australia

Diversity 2016, 8, 21; doi:10.3390/d8040021 S1 of S3 9 Supplementary Materials: Patterns of Sponge Biodiversity in the Pilbara, Northwestern Australia Jane Fromont, Muhammad Azmi Abdul Wahab, Oliver Gomez, Merrick Ekins, Monique Grol and John Norman Ashby Hooper 1. Materials and Methods 1.1. Collation of Sponge Occurrence Data Data of sponge occurrences were collated from databases of the Western Australian Museum (WAM) and Atlas of Living Australia (ALA) [1]. Pilbara sponge data on ALA had been captured in a northern Australian sponge report [2], but with the WAM data, provides a far more comprehensive dataset, in both geographic and taxonomic composition of sponges. Quality control procedures were undertaken to remove obvious duplicate records and those with insufficient or ambiguous species data. Due to differing naming conventions of OTUs by institutions contributing to the two databases and the lack of resources for physical comparison of all OTU specimens, a maximum error of ± 13.5% total species counts was determined for the dataset, to account for potentially unique (differently named OTUs are unique) or overlapping OTUs (differently named OTUs are the same) (157 potential instances identified out of 1164 total OTUs). The amalgamation of these two databases produced a complete occurrence dataset (presence/absence) of all currently described sponge species and OTUs from the region (see Table S1). The dataset follows the new taxonomic classification proposed by [3] and implemented by [4]. The latter source was used to confirm present validities and taxon authorities for known species names. The dataset consists of records identified as (1) described (Linnean) species, (2) records with “cf.” in front of species names which indicates the specimens have some characters of a described species but also differences, which require comparisons with type material, and (3) records as “operational taxonomy units” (OTUs) which are considered to be unique species although further assessments are required to establish their taxonomic status. -

Coupled Reductive and Oxidative Sulfur Cycling in the Phototrophic Plate of a Meromictic Lake T

Geobiology (2014), 12, 451–468 DOI: 10.1111/gbi.12092 Coupled reductive and oxidative sulfur cycling in the phototrophic plate of a meromictic lake T. L. HAMILTON,1 R. J. BOVEE,2 V. THIEL,3 S. R. SATTIN,2 W. MOHR,2 I. SCHAPERDOTH,1 K. VOGL,3 W. P. GILHOOLY III,4 T. W. LYONS,5 L. P. TOMSHO,3 S. C. SCHUSTER,3,6 J. OVERMANN,7 D. A. BRYANT,3,6,8 A. PEARSON2 AND J. L. MACALADY1 1Department of Geosciences, Penn State Astrobiology Research Center (PSARC), The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, USA 2Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA 3Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, USA 4Department of Earth Sciences, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, USA 5Department of Earth Sciences, University of California, Riverside, CA, USA 6Singapore Center for Environmental Life Sciences Engineering, Nanyang Technological University, Nanyang, Singapore 7Leibniz-Institut DSMZ-Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen, Braunschweig, Germany 8Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT, USA ABSTRACT Mahoney Lake represents an extreme meromictic model system and is a valuable site for examining the organisms and processes that sustain photic zone euxinia (PZE). A single population of purple sulfur bacte- ria (PSB) living in a dense phototrophic plate in the chemocline is responsible for most of the primary pro- duction in Mahoney Lake. Here, we present metagenomic data from this phototrophic plate – including the genome of the major PSB, as obtained from both a highly enriched culture and from the metagenomic data – as well as evidence for multiple other taxa that contribute to the oxidative sulfur cycle and to sulfate reduction. -

Yu-Chen Ling and John W. Moreau

Microbial Distribution and Activity in a Coastal Acid Sulfate Soil System Introduction: Bioremediation in Yu-Chen Ling and John W. Moreau coastal acid sulfate soil systems Method A Coastal acid sulfate soil (CASS) systems were School of Earth Sciences, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC 3010, Australia formed when people drained the coastal area Microbial distribution controlled by environmental parameters Microbial activity showed two patterns exposing the soil to the air. Drainage makes iron Microbial structures can be grouped into three zones based on the highest similarity between samples (Fig. 4). Abundant populations, such as Deltaproteobacteria, kept constant activity across tidal cycling, whereas rare sulfides oxidize and release acidity to the These three zones were consistent with their geological background (Fig. 5). Zone 1: Organic horizon, had the populations changed activity response to environmental variations. Activity = cDNA/DNA environment, low pH pore water further dissolved lowest pH value. Zone 2: surface tidal zone, was influenced the most by tidal activity. Zone 3: Sulfuric zone, Abundant populations: the heavy metals. The acidity and toxic metals then Method A Deltaproteobacteria Deltaproteobacteria this area got neutralized the most. contaminate coastal and nearby ecosystems and Method B 1.5 cause environmental problems, such as fish kills, 1.5 decreased rice yields, release of greenhouse gases, Chloroflexi and construction damage. In Australia, there is Gammaproteobacteria Gammaproteobacteria about a $10 billion “legacy” from acid sulfate soils, Chloroflexi even though Australia is only occupied by around 1.0 1.0 Cyanobacteria,@ Acidobacteria Acidobacteria Alphaproteobacteria 18% of the global acid sulfate soils. Chloroplast Zetaproteobacteria Rare populations: Alphaproteobacteria Method A log(RNA(%)+1) Zetaproteobacteria log(RNA(%)+1) Method C Method B 0.5 0.5 Cyanobacteria,@ Bacteroidetes Chloroplast Firmicutes Firmicutes Bacteroidetes Planctomycetes Planctomycetes Ac8nobacteria Fig. -

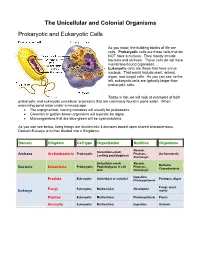

The Unicellular and Colonial Organisms Prokaryotic And

The Unicellular and Colonial Organisms Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells As you know, the building blocks of life are cells. Prokaryotic cells are those cells that do NOT have a nucleus. They mostly include bacteria and archaea. These cells do not have membrane-bound organelles. Eukaryotic cells are those that have a true nucleus. That would include plant, animal, algae, and fungal cells. As you can see, to the left, eukaryotic cells are typically larger than prokaryotic cells. Today in lab, we will look at examples of both prokaryotic and eukaryotic unicellular organisms that are commonly found in pond water. When examining pond water under a microscope… The unpigmented, moving microbes will usually be protozoans. Greenish or golden-brown organisms will typically be algae. Microorganisms that are blue-green will be cyanobacteria. As you can see below, living things are divided into 3 domains based upon shared characteristics. Domain Eukarya is further divided into 4 Kingdoms. Domain Kingdom Cell type Organization Nutrition Organisms Absorb, Unicellular-small; Prokaryotic Photsyn., Archaeacteria Archaea Archaebacteria Lacking peptidoglycan Chemosyn. Unicellular-small; Absorb, Bacteria, Prokaryotic Peptidoglycan in cell Photsyn., Bacteria Eubacteria Cyanobacteria wall Chemosyn. Ingestion, Eukaryotic Unicellular or colonial Protozoa, Algae Protista Photosynthesis Fungi, yeast, Fungi Eukaryotic Multicellular Absorption Eukarya molds Plantae Eukaryotic Multicellular Photosynthesis Plants Animalia Eukaryotic Multicellular Ingestion Animals Prokaryotic Organisms – the archaea, non-photosynthetic bacteria, and cyanobacteria Archaea - Microorganisms that resemble bacteria, but are different from them in certain aspects. Archaea cell walls do not include the macromolecule peptidoglycan, which is always found in the cell walls of bacteria. Archaea usually live in extreme, often very hot or salty environments, such as hot mineral springs or deep-sea hydrothermal vents. -

Archaeal Distribution and Abundance in Water Masses of the Arctic Ocean, Pacific Sector

Vol. 69: 101–112, 2013 AQUATIC MICROBIAL ECOLOGY Published online April 30 doi: 10.3354/ame01624 Aquat Microb Ecol FREEREE ACCESSCCESS Archaeal distribution and abundance in water masses of the Arctic Ocean, Pacific sector Chie Amano-Sato1, Shohei Akiyama1, Masao Uchida2, Koji Shimada3, Motoo Utsumi1,* 1University of Tsukuba, Tennodai, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8572, Japan 2National Institute for Environmental Studies, Onogawa, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8506, Japan 3Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology, Konan, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108-8477, Japan ABSTRACT: Marine planktonic Archaea have been recently recognized as an ecologically impor- tant component of marine prokaryotic biomass in the world’s oceans. Their abundance and meta- bolism are closely connected with marine geochemical cycling. We evaluated the distribution of planktonic Archaea in the Pacific sector of the Arctic Ocean using fluorescence in situ hybridiza- tion (FISH) with catalyzed reporter deposition (CARD-FISH) and performed statistical analyses using data for archaeal abundance and geochemical variables. The relative abundance of Thaum - archaeota generally increased with depth, and euryarchaeal abundance was the lowest of all planktonic prokaryotes. Multiple regression analysis showed that the thaumarchaeal relative abundance was negatively correlated with ammonium and dissolved oxygen concentrations and chlorophyll fluorescence. Canonical correspondence analysis showed that archaeal distributions differed with oceanographic water masses; in particular, Thaumarchaeota were abundant from the halocline layer to deep water, where salinity was higher and most nutrients were depleted. However, at several stations on the East Siberian Sea side of the study area and along the North- wind Ridge, Thaumarchaeota and Bacteria were proportionally very abundant at the bottom in association with higher nutrient conditions. -

Insights Into Archaeal Evolution and Symbiosis from the Genomes of a Nanoarchaeon and Its Inferred Crenarchaeal Host from Obsidian Pool, Yellowstone National Park

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Microbiology Publications and Other Works Microbiology 4-22-2013 Insights into archaeal evolution and symbiosis from the genomes of a nanoarchaeon and its inferred crenarchaeal host from Obsidian Pool, Yellowstone National Park Mircea Podar University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Kira S. Makarova National Institutes of Health David E. Graham University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Yuri I. Wolf National Institutes of Health Eugene V. Koonin National Institutes of Health See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_micrpubs Part of the Microbiology Commons Recommended Citation Biology Direct 2013, 8:9 doi:10.1186/1745-6150-8-9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Microbiology at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Microbiology Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Mircea Podar, Kira S. Makarova, David E. Graham, Yuri I. Wolf, Eugene V. Koonin, and Anna-Louise Reysenbach This article is available at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange: https://trace.tennessee.edu/ utk_micrpubs/44 Podar et al. Biology Direct 2013, 8:9 http://www.biology-direct.com/content/8/1/9 RESEARCH Open Access Insights into archaeal evolution and symbiosis from the genomes of a nanoarchaeon and its inferred crenarchaeal host from Obsidian Pool, Yellowstone National Park Mircea Podar1,2*, Kira S Makarova3, David E Graham1,2, Yuri I Wolf3, Eugene V Koonin3 and Anna-Louise Reysenbach4 Abstract Background: A single cultured marine organism, Nanoarchaeum equitans, represents the Nanoarchaeota branch of symbiotic Archaea, with a highly reduced genome and unusual features such as multiple split genes.