Guidebook on African Commodity and Derivatives Exchanges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

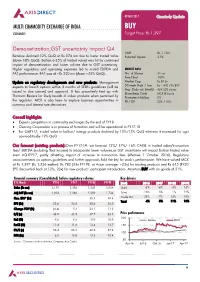

MULTI COMMODITY EXCHANGE of INDIA BUY EXCHANGES Target Price: Rs 1,397

09 MAY 2017 Quarterly Update MULTI COMMODITY EXCHANGE OF INDIA BUY EXCHANGES Target Price: Rs 1,397 Demonetization,GST uncertainty impact Q4 CMP : Rs 1,153 Revenue declined 12% QoQ at Rs 874 mn due to lower traded value Potential Upside : 21% (down 10% QoQ). Bullion (~35% of traded value) was hit by continued impact of demonetization and lower volume due to GST uncertainty. Higher regulatory and operating expenses led to muted EBITDA and MARKET DATA PAT performance. PAT was at ~Rs 220 mn (down ~35% QoQ). No. of Shares : 51 mn Free Float : 100% Update on regulatory developments and new products: Management Market Cap : Rs 59 bn expects to launch options within 3 months of SEBI’s guidelines (will be 52-week High / Low : Rs 1,420 / Rs 852 Avg. Daily vol. (6mth) : 429,628 shares issued in due course) and approval. It has proactively tied up with Bloomberg Code : MCX IB Equity Thomson Reuters for likely launch of index products when permitted by Promoters Holding : 0% the regulator. MCX is also keen to explore business opportunities in FII / DII : 23% / 36% currency and interest rate derivatives. Concall highlights ♦ Expects competition in commodity exchanges by the end of FY18 ♦ Clearing Corporation is in process of formation and will be operational in FY17-18 ♦ For Q4FY17, traded value in bullion/ energy products declined by 18%/13% QoQ whereas it increased for agri commoditiesby 19% QoQ Our forecast (existing products):Over FY17-19, we forecast 12%/ 17%/ 16% CAGR in traded value/transaction fees/ EBITDA (including float income) to incorporate lower volumes,as GST uncertainty will impact bullion traded value even inQ1FY17, partly offsetting impact of increase in transaction fees (effective 1 October 2016). -

Kicking the Bucket Shop: the Model State Commodity Code As the Latest Weapon in the State Administrator's Anti-Fraud Arsenal, 42 Wash

Washington and Lee Law Review Volume 42 | Issue 3 Article 6 Summer 6-1-1985 Kicking the Bucket Shop: The oM del State Commodity Code as the Latest Weapon in the State Administrator's Anti-Fraud Arsenal Julie M. Allen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr Part of the Securities Law Commons Recommended Citation Julie M. Allen, Kicking the Bucket Shop: The Model State Commodity Code as the Latest Weapon in the State Administrator's Anti-Fraud Arsenal, 42 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 889 (1985), https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol42/iss3/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington and Lee Law Review at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Law Review by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KICKING THE BUCKET SHOP: THE MODEL STATE COMMODITY CODE AS THE LATEST WEAPON IN THE STATE ADMINISTRATOR'S ANTI-FRAUD ARSENAL JuIE M. ALLEN* In April 1985, the North American Securities Administrators Association adopted the Model State Commodity Code. The Model Code is designed to regulate off-exchange futures and options contracts, forward contracts, and other contracts for the sale of physical commodities but not exchange-traded commodity futures contracts or exchange-traded commodity options. Specif- ically, the Model Code addresses the problem of boiler-rooms and bucket shops-that is, the fraudulent sale of commodities to the investing public. -

World Map of the Futures Field 3.Mmap - 2008-12-18

Albania Andorra Armenia Belarus Bosnia and Herzegovina Croatia (EU candidate) Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (EU candidate) Georgia Iceland Liechtenstein Moldova Monaco Montenegro Futurama Idébanken NTNU Norway Foresight University of Tromsö Non-EU Plausible Futures Club2015.ru Ru ssi a Moscow MP node San Marino Serbia European Futurists Conference Lucerne Futurizon Gottlieb Duttweiler Institut moderning Switzerland Prognos ROOS Office for Cultural Innovation Swissfuture - Swiss Society for Futures Studies Tüm Fütüristler Dernegi (MP node) Turkey (EU candidate) M-GEN Ukraine Vatican City State Institute for Future Studies Robert Jungk Bibliothek für Zukunftsfragen Austria RSA (MP node) Zukunftszentrum Tirol Institut Destrée (MP node) Kate Thomas & Kleyn Belgium Panopticon ForeTech Bulgaria Cyprus Czech Republic Future Navigator Instituttet for Fremtidsforskning Denmark Ministeriet for Videnskab, Teknologi och Udvikling Association of Professional Futurists Estonian Institute for Futures Studies Estonia Club of Rome Finland Futures Academy (MP node) Enhance Project Finland Futures Research Centre Foresight International Finnish Society for Futures Studies Finland Future Institute International TEKES National Technology Agency International Council for Science (ICSU) VTT International Institute for Forecasters Association Nationale de la Recherche Technique BIPE Network of European Technocrats Centre D'etudes Prospectiveset D'informations Internationales Committee for Information, Computer and Communications Policy Centre d'analyse -

Food Speculationspeculation Ploughing Through the Meanders in Food Speculation

PloughingPloughing throughthrough thethe meandersmeanders inin FoodFood SpeculationSpeculation Ploughing through the meanders in Food Speculation Collaborator Process by Place and date of writing: Bilbao, February 2011. Written by Mónica Vargas y Olivier Chantry from the (ODG) Observatori del Deute en la Globalització (Observatory on Debt in Globalization) of the Càtedra UNESCO de Sostenibilitat Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (Po- lytechnic University of Catalonia’s UNESCO Chair on Sustainability) and edi- ted by Gustavo Duch from Revista Soberanía Alimentaria, Biodiversidad y Culturas (Food Sovereignty, Biodiversity and Cultures Magazine). With the support of Grain www.grain.org and of Mundubat www.mundubat.org This material may be freely shared, although we would appreciate your quoting the source. Co-financed by: “This publication has been produced with the financial support of the Spanish Agency for International Co-operation for Development (AECID). The contents of this publica- tion are the exclusive responsibility of Mundubat and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the AECID.” Index Introduction 5 1. Food speculation: what is it and where does it originate from? 8 Initial definitions 8 Origin and functioning of futures markets 9 In the 1930’s: a regulation that legitimized speculation 12 2. The scaffolding of 21st-century food speculation 13 Liberalization of financial and agricultural markets: two parallel processes 13 Fertilizing the ground for speculation 14 Ever more complex financial engineering 15 3. Agribusiness’ -

Private Ordering at the World's First Futures Exchange

Michigan Law Review Volume 98 Issue 8 1999 Private Ordering at the World's First Futures Exchange Mark D. West University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Contracts Commons, Law and Economics Commons, Legal History Commons, and the Securities Law Commons Recommended Citation Mark D. West, Private Ordering at the World's First Futures Exchange, 98 MICH. L. REV. 2574 (2000). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol98/iss8/8 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRIVATE ORDERING AT THE WORLD'S FIRST FUTURES EXCHANGE Mark D. West* INTRODUCTION Modern derivative securities - financial instruments whose value is linked to or "derived" from some other asset - are often sophisti cated, complex, and subject to a variety of rules and regulations. The same is true of the derivative instruments traded at the world's first organized futures exchange, the Dojima Rice Exchange in Osaka, Japan, where trade flourished for nearly 300 years, from the late sev enteenth century until shortly before World War II. This Article analyzes Dojima's organization, efficiency, and amalgam of legal and extralegal rules. In doing so, it contributes to a growing body of litera ture on commercial self-regulation1 while shedding new light on three areas of legal and economic theory. -

Elixir Journal

50958 Garima saxena and Rajeshwari kakkar / Elixir Inter. Law 119 (2018) 50958-50966 Available online at www.elixirpublishers.com (Elixir International Journal) International Law Elixir Inter. Law 119 (2018) 50958-50966 Performance of Stock Markets in the Last Three Decades and its Analysis Garima saxena and Rajeshwari kakkar Amity University, Noida. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Stock market refers to the market where companies stocks are traded with both listed Received: 6 April 2018; and unlisted securities. Indian stock market is also called Indian equity market. Indian Received in revised form: equity market was not organized before independence due to the agricultural conditions, 25 May 2018; undeveloped industries and hampering by foreign business enterprises. It is one of the Accepted: 5 June 2018; oldest markets in India and started in 18th century when east India Company started trading in loan securities. During post-independence the capital market became more Keywords organized and RBI was nationalized. As we analyze the performance of stock markets Regulatory framework, in the last three decades, it comes near enough to a perfectly aggressive marketplace Reforms undertaken, permitting the forces of demand and delivers an inexpensive degree of freedom to Commodity, perform in comparison to other markets in particular the commodity markets. list of Deposit structure, reforms undertaken seeing the early nineteen nineties include control over problem of Net worth, investors. capital, status quo of regulator, screen primarily based buying and selling and threat management. Latest projects include the t+2 rolling settlement and the NSDL was given the obligation to assemble and preserve an important registry of securities marketplace participants and experts. -

Today's Top Research Idea Market Snapshot Research Covered

12 May 2021 ASIAMONEY Brokers Poll 2020 (India) Today’s top research idea Godrej Consumer : New leadership offers scope for transformative change Upgrade to Buy We view Mr. Sudhir Sitapati’s appointment as MD and CEO of GCPL as a potentially transformative event in the fortunes of the company. Mr. Sitapati comes with impressive experience in heading HUVR’s F&R business and as part of the senior management team in the Detergents business, which Market snapshot have done very well under his tenure and where marketing campaigns in both segments have a high value impact. His appointment as MD and CEO for five Equities - India Close Chg .% CYTD.% years, as well has his relative young age (mid-40s), gives him adequate time to Sensex 49,162 -0.7 3.0 Nifty-50 14,851 -0.6 6.2 formulate and implement strategic changes. Nifty-M 100 24,972 0.8 19.8 The underpenetrated Household Insecticides (HI, ~70%/50% penetration in Equities-Global Close Chg .% CYTD.% urban/rural) and Hair Color (~30% penetration) categories could greatly S&P 500 4,152 -0.9 10.5 benefit from Mr. Sitapati’s past experience, where GCPL has struggled to Nasdaq 13,389 -0.1 3.9 boost penetration. FTSE 100 6,948 -2.5 7.5 DAX 15,120 -1.8 10.2 After more than a decade of being Neutral on the company (downgraded to Hang Seng 10,432 -2.1 -2.9 Neutral in Aug’10), a stand that has been vindicated particularly in the past Nikkei 225 28,609 -3.1 4.2 five years, we are upgrading the stock to Buy. -

The Evolution of European Traded Gas Hubs

December 2015 The evolution of European traded gas hubs OIES PAPER: NG 104 Patrick Heather The contents of this paper are the authors’ sole responsibility. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies or any of its members. Copyright © 2015 Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (Registered Charity, No. 286084) This publication may be reproduced in part for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgment of the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. ISBN 978-1-78467-046-7 i December 2015: The evolution of European traded gas hubs Preface In following the process of the transition of continental European gas pricing over the past decade, research papers published by the OIES Gas Programme have increasingly observed that the move from oil-indexed to hub or market pricing is a clear secular trend, strongest in northwest Europe but spreading southwards and eastwards. Certainly at an overview level, such a statement appears to be supported by the measurable levels of trading volumes and liquidity. The annual surveys on pricing of wholesale gas undertaken by the IGU also lend quantitative evidence of these trends. So if gas hub development dynamics in Europe are analogous to ‘ripples in a pond’ spreading outwards from the UK and Dutch ‘epicentre’, what evidence do we have that national markets and planned or nascent hubs at the periphery are responding? This is more than an academic question. -

(Ifs) PART 2: DRIVING the DRIVERS and INDICES

FREDERICK S. PARDEE CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL FUTURES EXPLORE UNDERSTAND SHAPE WORKING PAPER 2005.05.24.b FORECASTING PRODUCTIVITY AND GROWTH WITH INTERNATIONAL FUTURES (IFs) PART 2: DRIVING THE DRIVERS AND INDICES Author: Barry B. Hughes May 2005 Note: If cited or quoted, please indicate working paper status. PARDEE.DU.EDU Forecasting Productivity and Growth in International Futures (IFs) Part 2: Driving the Drivers and Indices Table of Contents 1. The Objectives and Context ........................................................................................ 1 2. Social Capital: Governance Quality ........................................................................... 4 2.1 Existing Measures/Indices .................................................................................. 4 2.2 Forward Linkages: Does Governance Affect Growth? ..................................... 7 2.3 Backward Linkages (Drivers): How Forecast Governance Effectiveness? ..... 11 2.4 Specifics of Implementation in IFs: Backward Linkages ................................ 14 2.5 Comments on Other Aspects of Social Capital ................................................. 16 3. Physical Capital: Modern (or Information-Age) Infrastructure ............................... 17 3.1 Existing Infrastructure Indices: Is There a Quick and Easy Approach? .......... 18 3.2 Background: Conceptual, Data and Measurement Issues ................................ 19 3.3 Infrastructure in IFs .......................................................................................... -

Training Manual Frederick S. Pardee Center for Ifs Josef Korbel School of International Studies Univ

International Futures (IFs) Training Manual Frederick S. Pardee Center for IFs Josef Korbel School of International Studies University of Denver www.ifs.du.edu | www.ifsforums.du.edu Contact: [email protected] This manual was written by the following: Barry B Hughes Mohammod T Irfan Eli Margolese -Malin Jonathan D Moyer Carey Neill José Sol órzano Table of Contents 1 General Overview ............................................................................................................................. 4 2 Introduction to IFs ............................................................................................................................. 5 2.1 What IFs Can Do ............................................................................................................................ 6 2.2 The Structure of IFs ....................................................................................................................... 7 2.3 IFs Philosophy ................................................................................................................................ 9 2.4 IFs Vocabulary ............................................................................................................................. 10 2.5 Geographic Representation in IFs ............................................................................................... 11 2.6 Key Features of IFs ...................................................................................................................... 12 3 Introduction to Forecasting -

January 19,2006 Rule 10A-1

SIDLEY AUSTIN LLP BElJlNG GENEVA SAN FRANCISCO 787 SEVENTH AVENUE BRUSSELS HONG KONG SHANGHAI NEW YORK. NY 10018 CHICAGO LONDON SINGAPORE 2128395300 DALLAS LOS ANGELES fOKYO 212 839 5599 FAX NEW YORK WASHINGTON. DC I FOUNDED 1866 January 19,2006 Rule 10a-1; Rule 200(g) of Regulation SHO; Rule 10 1 and James A. Brigagliano, Esq. 102 of Regulation M; Section Assistant Director, Trading Practices ll(d)(l) and Rule lldl-2 ofthe Office of Trading Practices and Processing Securities Exchange Act of 1934, Division of Market Regulation Securities and Exchange Commission 100 F Street, N.E. Washington, DC 20549 Re: Request of DB Commodity Index Tracking Fund and DB Commodity Services LLC for Exemptive, Interpretative or No-Action Relief from Rule 10a-1 under, Rule 200(g) of Regulation SHO under, Rules 101 and 102 of Regulation M under, Section ll(d)(l) of and Rule lldl-2 under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended Dear Mr. Brigagliano: We are writing on behalf of DB Commodity Index Tracking Fund (the "Fund"), a ~elawkestatutory trust and a public commodity pool, and DB Commodity Services LLC ("DBCS"), which will be the registered commodity pool operator ("CPO) and managing owner (the "Managing Owner") of the Fund. The Fund and the Managing Owner (a) on their own behalf and (b) on behalf of (1) the DB Commodity Index Tracking Master Fund (the "Master Fund"); (2) ALPS Distributors, Inc. (the "Distributor"), which provides certain distribution-related administrative services for the Fund; (3) the American Stock Exchange ("'AMEX") and any -

Lfs Broking Private Limited

LFS BROKING PRIVATE LIMITED (Member BSE, NSE, MCX & CDSL) A P P L IC A T IO N F O R A D D IT IO N A L S EG M E N T / EX C H A N G E F O R T R A D IN G A C C O U N T Client Code Client Name Branch/ AP Code Branch/ AP Name LFS BROKING PVT. LTD. CIN NO.: U67190PN2011PTC140719 Registered Office Address: Office No. 311/75, 3rd Floor, Shrinath Plaza, ‘B’ Wing, F.C. Road, Shivaji Nagar, Bhamburda, Pune - 411005. Correspondence Office Address: Unit No. 08, 2nd Floor, Prabhadevi Industrial Estate, 408 Veer Savarkar Marg, Prabhadevi, Mumbai - 400025. Tel: (91) 22-49228222 Fax: (91) 22-49228221 Website: www.lfsbroking.in Exchange Segment SEBI Registration No. Member Code Date of Registration BSE CASH/FO INZ 000101238 6628 February 20, 2017 NSE CASH/FO/CD INZ 000101238 90022 February 20, 2017 MCX COMMODITY INZ 000101238 56350 February 20, 2017 CDSL Depository Participant IN-DP-CDSL-363-2018 85400 April 05, 2018 IL & FS Securities Services Ltd. IL&FS House, Plot No.14, Raheja Vihar, Chandivali, Clearing Member for NSE (FO & CD) Segments: Andheri (E), Mumbai - 400072. Tel.: 022-42493000 www.ilfsdp.com SMC Comtrade Ltd. Clearing Member for MCX Commodity 11/6B, Shanti Chamber, Pusa Road, New Delhi ‐ 110005. Derivatives Segment: Tel.: 011-30111000 www.smcindiaonline.com Mr. Anand Tamhane Compliance Officer Details: Ph : 022-49228222 Ext: 225 Email id : [email protected] Mr. Saiyad Jiyajur Rahaman Director/CEO Details: Ph : 022-49228222 Ext. 220 Email id : [email protected] For any grievance / dispute please contact LFS BROKING PVT.