Jakóbowicz (Jakobowicz, Jakubowicz) Surname Variants in Holocaust Records

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bayou Branches JEWISH GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY of NEW ORLEANS

Bayou Branches JEWISH GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY OF NEW ORLEANS VOLUME 7 NUMBER 1 SPRING/SUMMER 2001 GENEALOGY INSTITUTE OPENS AT CENTER FOR JEWISH HISTORY IN NEW YORK CITY JGSNO members are invited to submit articles for the All JGS members are welcome to visit, write, Jewish History, they are working with the Jew- next issue of Bayou or call the new Center for Jewish History Ge- ish genealogy community to serve family his- nealogy Institute, located in New York City. tory researchers at every level, and the Center Branches. All topics related The Center for Jewish History embodies the Genealogy Institute (CGI) has been formed to to genealogy are welcome. unique partnership of five major institutions carry out this critical aspect of the mission. Please submit before July of Jewish scholarship, history and art: Ameri- A comprehensive collection of genealogy refer- 31 to Carol Levy Monahan can Jewish Historical Society, American ence works also is being built. (The Genealogy at: Sephardi Federation, Leo Baeck Institute, Institute gladly accepts donations of reference Yeshiva University Museum and the YIVO In- books; anyone wishing to donate family histo- 4628 Fairfield Street stitute for Jewish Research. The Center ries, photographs or primary documents Metairie, LA 70006 serves the worldwide academic and general should contact the appropriate partner institu- communities with combined holdings of ap- tion.) proximately 100 million archival documents, Inside this issue: a half million books, and thousands of photo- Inquiries, visits, and support are welcome. Contact: graphs, artifacts, paintings and textiles-the Book Donations to East Jefferson 2 largest repository documenting the Jewish Center Genealogy Institute Regional Library –Update experience outside of Israel. -

Resource Center

38 RESOURCE CENTER RESOURCE CENTER The Resource Center welcomes you to explore the variety of computer databases, reference books, and translation services available in our two Resource Center rooms, conveniently located across from each other on the 4th floor. Books & Translations Winthrop Room - 4th floor Databases & Consultations Whittier Room - 4th floor Hours (for both rooms) Sunday 1pm – 6pm Monday 9am – 6pm Tuesday Winthrop 9am – 6pm Whittier 9am – 9pm* Wednesday & Thursday 9am – 6pm Friday 9am – 12pm *ProQuest Databases are available only on Tuesday, 9am – 9pm BOOKS & TRANSLATIONS (WINTHROP ROOM – 4TH FLOOR) This room includes selected reference books that will help you start your research, discover your surname origins, learn about country-specific genealogical resources, understand Hebrew gravestone inscriptions, etc. A complete listing of the titles is available in the Syllabus and in the Winthrop Room. Books can be borrowed for use only in the Winthrop Room by leaving a government-issued photo ID or passport with Resource Center staff. Translation services will be provided by appointment only and the appointments are scheduled for 20 minutes each. Please come to the Winthrop Room to sign up. DATABASES & CONSULTATIONS (WHITTIER ROOM – 4TH FLOOR) 30 computers will be available for complimentary searching of more than 20 databases. Most of these databases are normally available only by subscription or membership fees. The computers are available on a first-come-first- served basis, and their use is limited to 30 minutes when there are people waiting to use them. Special research assistance will be provided by representatives of JewishGen, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Ancestry.com and the American Jewish Historical Society-New England Archives. -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

The Role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin Struggle for Independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 1-1-1967 The role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin struggle for independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649. Andrew B. Pernal University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Pernal, Andrew B., "The role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin struggle for independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649." (1967). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 6490. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/6490 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. THE ROLE OF BOHDAN KHMELNYTSKYI AND OF THE KOZAKS IN THE RUSIN STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE FROM THE POLISH-LI'THUANIAN COMMONWEALTH: 1648-1649 by A ‘n d r e w B. Pernal, B. A. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History of the University of Windsor in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Faculty of Graduate Studies 1967 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Cesja Adresy Punktów Partners

Miasto Kod pocztowy Ulica Nazwa Punktu Sprzedaży Telefon Aleksandrów Kujawski 87-700 Słowackiego 73A Martel Gsm 542826140 Bartoszyce 11-200 Bohaterów Warszawy 111 Marcomtel 791153900 Będzin 41-253 11 Listopada 10 KKTEL 722030560 Biała Podlaska 21-500 Jana III Sobieskiego 9 Telakces.com wyspa 517-949-391 Białystok 15-281 Legionowa 9/1 lok.33 MAR-TEL Marcin Mazewski 506704994 Białystok 15-703 Zwycięstwa 8 lok. 11. Bazar Madro MARTEL Marek Korol 505600600 Białystok 15-101 Jurowiecka 1 Telakces.com wyspa 737881996 Białystok 15-281 Legionowa 9/1 MEDIA-KOM lok. 8 857451313 Białystok 15-092 Sienkiewicza 26 MEDIA-KOM 602506009 Białystok 15-277 Świętojańska 15 Telakces.com 665 006 669 Białystok 15-281 Legionowa 9/1 lok. 29 MR tech Rafał Jackowski 600803605 Białystok 15-281 Legionowa 9/1 ZAKŁAD USŁUGOWY "TOMSAT" 602378724 Białystok 15-660 ul. Wrocławska 20 Telakces.com 737769937 Białystok 15-101 Jurowiecka 1 Telakces.com Białystok 15-814 Gen. Zygmunta Berlinga 10 lok. 30 Miltom Tomasz Milewski 535749575 Białystok 15-660 Wrocławska 20 Telakces.com wyspa Bielsk Podlaski 17-100 Mickiewicza 108/7 ŻUBER - GSM 730482757 Bielsko Biała 43-300 Leszczyńska 20 Telakces.com wyspa 737809022 Bielsko Biała 43-300 Gen.Andersa 81 FHU MOBILSTAR 797844441 Bielsko Biała 43-300 Leszczyńska 20 DARIUSZ RZEMPIEL FHU MOBILSTAR 660450902 Bielsko Biała 43-300 Sarni Stok 2 ART POWER 511383511 Bielsko Biała 43-300 Plac Wojska Polskiego 9 MPhone 338224454 BIELSKO BIAŁA 43-300 MOSTOWA 5 Telakces.com wyspa 799177388 Bielsko Biała 43-300 Sarni Stok 2 Telakces.com wyspa 799177388 Bogatynia 59-920 Kościuszki 22 XPRESERWIS Paweł Fułat 793933440 Brzeg Dolny 56-120 Tęczowa 14 LUKSA Łukasz Sąsiada 603472677 Brzeziny 95-060 Traugutta 5 PPHU FENIKS Piotr Jastrzębski 692495891 Bydgoszcz 85-094 M.C. -

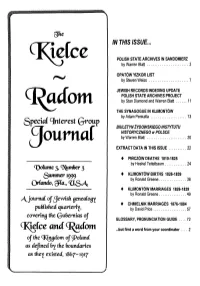

{Journal by Warren Blatt 2 0 EXTRACT DATA in THIS ISSUE 2 2

/N TH/S /SSUE... POLISH STATE ARCHIVES IN SANDOMIERZ by Warren Blatt 3 OPATÔWYIZKORLIST by Steven Weiss 7 JEWISH RECORDS INDEXING UPDATE POLISH STATE ARCHIVES PROJECT by Stan Diamond and Warren Blatt 1 1 THE SYNAGOGUE IN KLIMONTÔW by Adam Penkalla 1 3 Qpedd interest Qroup BIULETYN ZYDOWSKIEGOINSTYTUTU HISTORYCZNEGO w POLSCE {journal by Warren Blatt 2 0 EXTRACT DATA IN THIS ISSUE 2 2 • PINCZÔ W DEATHS 1810-182 5 by Heshel Teitelbaum 2 4 glimmer 1999 • KLIMONTÔ W BIRTHS 1826-183 9 by Ronald Greene 3 8 • KLIMONTÔ W MARRIAGES 1826-183 9 by Ronald Greene 4 9 o • C H Ml ELN IK MARRIAGES 1876-188 4 covering tfte Qufoernios of by David Price 5 7 and <I^ GLOSSARY, PRONUNCIATION GUIDE ... 72 ...but first a word from your coordinator 2 ojtfk as <kpne as tfie^ existed, Kieke-Radom SIG Journal, VoL 3 No. 3 Summer 1999 ... but first a word from our coordinator It has been a tumultuous few months since our last periodical. Lauren B. Eisenberg Davis, one of the primary founders of our group, Special Merest Group and the person who so ably was in charge of research projects at the SIG, had to step down from her responsibilities because of a serious journal illness in her family and other personal matters. ISSN No. 1092-800 6 I remember that first meeting in Boston during the closing Friday ©1999, all material this issue morning hours of the Summer Seminar. Sh e had called a "birds of a feather" meeting for all those genealogists interested in forming a published quarterly by the special interest group focusing on the Kielce and Radom gubernias of KIELCE-RADOM Poland. -

Moses Mendelssohn and the Jewish Historical Clock Disruptive Forces in Judaism of the 18Th Century by Chronologies of Rabbi Families

Moses Mendelssohn and The Jewish Historical Clock Disruptive Forces in Judaism of the 18th Century by Chronologies of Rabbi Families To be given at the Conference of Jewish Genealogy in London 2001 By Michael Honey I have drawn nine diagrams by the method I call The Jewish Historical Clock. The genealogy of the Mendelssohn family is the tenth. I drew this specifically for this conference and talk. The diagram illustrates the intertwining of relationships of Rabbi families over the last 600 years. My own family genealogy is also illustrated. It is centred around the publishing of a Hebrew book 'Megale Amukot al Hatora' which was published in Lvov in 1795. The work of editing this book was done from a library in Brody of R. Efraim Zalman Margaliot. The book has ten testimonials and most of these Rabbis are shown with a green background for ease of identification. The Megale Amukot or Rabbi Nathan Nata Shpiro with his direct descendants in the 17th century are also highlighted with green backgrounds. The numbers shown in the yellow band are the estimated years when the individuals in that generation were born. For those who have not seen the diagrams of The Jewish Historical Clock before, let me briefly explain what they are. The Jewish Historical Clock is a system for drawing family trees ow e-drmanfly 1 I will describe to you the linkage of the Mendelssohn family branch to the network of orthodox rabbis. Moses Mendelssohn 1729-1786 was in his time the greatest Jewish philosopher. He was one of the first Jews to write in a modern language, German and thus opened the doors to Jewish emancipation so desired by the Jewish masses. -

Polish-Jewish Genealogical Research Handout

Polish-Jewish Genealogical Research Warren Blatt HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF POLISH BORDER CHANGES: 1795 — 3rd and final partition of Poland; Poland ceases to exist as a nation. Northern and western areas (Poznañ, Kalisz, Warsaw, £om¿a, Bia³ystok) taken by Prussia; Eastern areas (Vilna, Grodno, Brest) taken by Russia; Southern areas (Kielce, Radom, Lublin, Siedlce) becomes part of Austrian province of West Galicia. 1807 — Napoleon defeats Prussia; establishes Grand Duchy of Warsaw from former Prussian territory. 1809 — Napoleon defeats Austria; West Galicia (includes most of future Kielce-Radom-Lublin-Siedlce gubernias) becomes part of Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. 1815 — Napoleon defeated at Waterloo; Congress of Vienna establishes “Kingdom of Poland” (aka “Congress Poland” or “Russian Poland”) from former Duchy of Warsaw, as part of the Russian Empire; Galicia becomes part of Austro-Hungarian Empire; Western provinces are retained by Prussia. 1918 — End of WWI. Poland reborn at Versailles, but only comprising 3/5ths the size of pre-partition Poland. 1945 — End of WWII. Polish borders shift west: loses territory to U.S.S.R., gains former German areas. LOCATING THE ANCESTRAL SHTETL: _______, Gemeindelexikon der Reichsrate vertretenen Königreiche und Länder [Gazetteer of the Crown Lands and Territories Represented in the Imperial Council]. (Vienna, 1907). {Covers former Austrian territory}. _______, Spis Miejscowoœci Polskiej Rzeczypospolitej Ludowej [Place Names in the Polish Peoples' Republic]. (Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Komunicacji i Lacznosci, 1967). _______, Wykas Wredowych Nazw Miejscowoœci w Polsce [A List of Official Geographic Place Names in Poland]. (Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Akcydensowe, 1880). Barthel, Stephen S. and Daniel Schlyter. “Using Prussian Gazetteers to Locate Jewish Religious and Civil Records in Poznan”, in Avotaynu, Vol. -

Re-Branding a Nation Online: Discourses on Polish Nationalism and Patriotism

Re-Branding a Nation Online Re-Branding a Nation Online Discourses on Polish Nationalism and Patriotism Magdalena Kania-Lundholm Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Sal IX, Universitets- huset, Uppsala, Friday, October 26, 2012 at 10:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Kania-Lundholm, M. 2012. Re-Branding A Nation Online: Discourses on Polish Nationalism and Patriotism. Sociologiska institutionen. 258 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 978-91-506-2302-4. The aim of this dissertation is two-fold. First, the discussion seeks to understand the concepts of nationalism and patriotism and how they relate to one another. In respect to the more criti- cal literature concerning nationalism, it asks whether these two concepts are as different as is sometimes assumed. Furthermore, by problematizing nation-branding as an “updated” form of nationalism, it seeks to understand whether we are facing the possible emergence of a new type of nationalism. Second, the study endeavors to discursively analyze the ”bottom-up” processes of national reproduction and re-definition in an online, post-socialist context through an empirical examination of the online debate and polemic about the new Polish patriotism. The dissertation argues that approaching nationalism as a broad phenomenon and ideology which operates discursively is helpful for understanding patriotism as an element of the na- tionalist rhetoric that can be employed to study national unity, sameness, and difference. Emphasizing patriotism within the Central European context as neither an alternative to nor as a type of nationalism may make it possible to explain the popularity and continuous endur- ance of nationalism and of practices of national identification in different and changing con- texts. -

Reference Books on Jewish Names

Courtesy of the Ackman & Ziff Family Genealogy Institute June 2007 Reference Books On Jewish Names Ames, Winthrop. What Shall We Name the Baby? New York: Simon & Schuster, 1935. REF YIVO CS 2367 .A4 1935 Bahlow, Hans. Dictionary of German Names: Madison, WI: Max Kade Institute for German American Studies, 2002. REF LBI CS 2541 B34 D53 Beider, Alexander. A Dictionary of Ashkenazic Given Names: Their Origins, Structure, Pronunciation, and Migrations. Bergenfield, NJ: Avotaynu, 2001, 682 pp. Identifies more than 15,000 given names derived from 735 root names. Includes a 300page thesis on the origins, structure, pronunciation, and migrations of Ashkenazic given names. Genealogy Institute CS 3010 .B18 Beider, Alexander. A Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from Galicia . Avotaynu, 2004. Covers 25,000 different surnames used by Jews in Galicia., describing the districts within Galicia where the surname appeared, the origin of the meaning of the name, and the variants found. Genealogy Institute . CS 3010 .Z9 G353 2004 Beider, Alexander. A Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from the Kingdom of Poland. Teaneck, NJ: Avotaynu, Inc., 1996, 608 pp. More than 32,000 Jewish surnames with origins in that part of the Russian Empire known as the Kingdom of Poland or Congress Poland. Genealogy Institute CS 3010 .B419 Beider, Alexander. A Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from the Russian Empire. Teaneck, NJ: Avotaynu, Inc., 1993, 784 pp. A compilation of 50,000 Jewish surnames from the Russian Pale of Settlement describing their geographic distribution within the Russian Empire at the start of the 20th century, an explanation of the meaning of the name, and spelling variants. -

DNA Evidence of a Croatian and Sephardic Jewish Settlement on the North Carolina Coast Dating from the Mid to Late 1500S Elizabeth C

International Social Science Review Volume 95 | Issue 2 Article 2 DNA Evidence of a Croatian and Sephardic Jewish Settlement on the North Carolina Coast Dating from the Mid to Late 1500s Elizabeth C. Hirschman James A. Vance Jesse D. Harris Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/issr Part of the Anthropology Commons, Communication Commons, Genealogy Commons, Geography Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Political Science Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hirschman, Elizabeth C.; Vance, James A.; and Harris, Jesse D. () "DNA Evidence of a Croatian and Sephardic Jewish Settlement on the North Carolina Coast Dating from the Mid to Late 1500s," International Social Science Review: Vol. 95 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/issr/vol95/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Nighthawks Open Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Social Science Review by an authorized editor of Nighthawks Open Institutional Repository. DNA Evidence of a Croatian and Sephardic Jewish Settlement on the North Carolina Coast Dating from the Mid to Late 1500s Cover Page Footnote Elizabeth C. Hirschman is the Hill Richmond Gott rP ofessor of Business at The nivU ersity of Virginia's College at Wise. James A. Vance is an Associate Professor of Mathematics at The nivU ersity of Virginia's College at Wise. Jesse D. Harris is a student studying Computer Science -

How Much Conrad in Conrad Criticism?: Conrad's Artistry, Ideological

Yearbook of Conrad Studies (Poland) Vol. 13 2018, pp. 41–54 doi: 10.4467/20843941YC.18.004.11239 HOW MUCH CONRAD IN CONRAD CRITICISM?: CONRAD’S ARTISTRY, IDEOLOGICAL MEDIATIZATION AND IDENTITY A COMMEMORATIVE ADDRESS ON THE 160TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE WRITER’S BIRTH Grażyna Maria Teresa Branny Jesuit University Ignatianum in Kraków Abstract: The eponymous question of the present address as well as its main premise concern the issue of reading Conrad as opposed to the issue of Conrad’s readings. Although the writer insisted on the priority of artistic expression in his oeuvres over their thematic content, he tends to be ana- lyzed with a view to precedence of content over form. Moreover, his application in his less known short fiction of the then novel modernist device of denegation usually ascribed to Faulkner, is hardly given its due in criticism. What distorts Conrad is, likewise, ideological mediatization of his fiction and biography. And, last but not least, comes insufficient appreciation among Western Conradians of the significance for his writings of his Polish background, and especially his border- land szlachta heritage, where also Polish criticism has been at fault. As emphasized, in comparison with Conrad’s Englishness, which comes down to the added value of his home, family, friends, and career in England as well as the adopted language, his Polishness is about l’âme: the patriotic spirit of Conrad’s ancestry, traumatic childhood experience, Polish upbringing and education, sen- sibilities and deeply felt loyalties deriving from his formative years in Poland. Therefore, one of the premises put forward in the present address is that perhaps Conrad should be referred to as an English writer with his Polish identity constantly inscribed and reinscribed into the content and form of his oeuvres, rather than simply an English writer of Polish descent as he is now.