The Development of the Turbojet Engine in Britain and Germany As a Lens for Future Developments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Luftwaffe Wasn't Alone

PIONEER JETS OF WORLD WAR II THE LUFTWAFFE WASN’T ALONE BY BARRETT TILLMAN he history of technology is replete with Heinkel, which absorbed some Junkers engineers. Each fac tory a concept called “multiple independent opted for axial compressors. Ohain and Whittle, however, discovery.” Examples are the incandes- independently pursued centrifugal designs, and both encoun- cent lightbulb by the American inventor tered problems, even though both were ultimately successful. Thomas Edison and the British inventor Ohain's design powered the Heinkel He 178, the world's first Joseph Swan in 1879, and the computer by jet airplane, flown in August 1939. Whittle, less successful in Briton Alan Turing and Polish-American finding industrial support, did not fly his own engine until Emil Post in 1936. May 1941, when it powered Britain's first jet airplane: the TDuring the 1930s, on opposite sides of the English Chan- Gloster E.28/39. Even so, he could not manufacture his sub- nel, two gifted aviation designers worked toward the same sequent designs, which the Air Ministry handed off to Rover, goal. Royal Air Force (RAF) Pilot Officer Frank Whittle, a a car company, and subsequently to another auto and piston 23-year-old prodigy, envisioned a gas-turbine engine that aero-engine manufacturer: Rolls-Royce. might surpass the most powerful piston designs, and patented Ohain’s work detoured in 1942 with a dead-end diagonal his idea in 1930. centrifugal compressor. As Dr. Hallion notes, however, “Whit- Slightly later, after flying gliders and tle’s designs greatly influenced American savoring their smooth, vibration-free “Axial-flow engines turbojet development—a General Electric– flight, German physicist Hans von Ohain— were more difficult built derivative of a Whittle design powered who had earned a doctorate in 1935— to perfect but America's first jet airplane, the Bell XP-59A became intrigued with a propeller-less gas- produced more Airacomet, in October 1942. -

MTU-Museum Triebwerksgeschichte – Gestern, Heute Und Morgen MTU Museum 07 2009 01.Qxd 27.08.2009 13:47 Uhr Seite 4

MTU_Museum_07_2009_01.qxd 27.08.2009 13:47 Uhr Seite 3 MTU-Museum Triebwerksgeschichte – gestern, heute und morgen MTU_Museum_07_2009_01.qxd 27.08.2009 13:47 Uhr Seite 4 Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort 3 Unternehmen mit Tradition und Zukunft 4 Bewegte Geschichte 5 GP7000 – Antrieb für den Mega-Airbus 8 PW6000 – Antrieb des kleinen Airbus A318 8 EJ200 – Schub für den Eurofighter 9 PW4000 – Triebwerk der Boeing B777-200 10 MTR390 – Triebwerk des Tigers 10 V2500 – Antrieb für den Airbus A320 11 PW500 – Antrieb für Geschäftsreiseflugzeuge 12 RR250-C20 – Antrieb für Hubschrauber 12 RB199 – Antrieb des Tornado 13 CF6 – Power für Großraumflugzeuge 14 Lycoming GO-480-B1A6 – Lizenzfertigung bei BMW 15 MTU7042 – Erprobung einer LKW-Gasturbine 15 T64-MTU-7 – Lizenzbau in Deutschland 16 RB145R – Antrieb des VJ101C 16 RB193-12 – Antrieb für Senkrechtstarter 17 RB153 – Antrieb des VJ101E 17 J79 – Triebwerk des Starfighters 18 Tyne – Antrieb der Transall 19 BMW 6022 – Antrieb für den Bo105 19 DB 720 – Daimler-Nachkriegsära beginnt 20 BMW 801 – erster deutscher Doppelsternmotor 20 BMW 114 – Diesel-Flugmotor 21 BMW 003E – Schub für den Volksjäger 22 Riedel-Anlasser – Starter für Strahltriebwerke 23 BRAMO 323 R-1 „Fafnir“ – erfolgreichster BRAMO-Flugmotor 23 Daimler-Benz DB 605 – der „kleine“ Mercedes-Benz-Flugmotor 24 BMW 132 – Nachfolger des Hornet-Motors 25 Sh14A – erfolgreichster Siemens-Flugmotor 26 BMW VI – Erfolgsmotor der 1920er-Jahre 26 Daimler-Benz F4A – Vorläufer der DB 600-Familie 27 Daimler D IIIa – Ära der Kolbenflugmotoren beginnt 27 Exponate 28 Chirurg der Motoren 31 2 MTU_Museum_07_2009_01.qxd 27.08.2009 13:47 Uhr Seite 5 Vorwort Die Museumswelt wird nicht nur von großen Ausstellungen und Kunstgalerien jeder Couleur geprägt, sondern auch von technischen Samm- lungen, wie etwa dem Deutschen Museum in München. -

Comparison of Helicopter Turboshaft Engines

Comparison of Helicopter Turboshaft Engines John Schenderlein1, and Tyler Clayton2 University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, 80304 Although they garnish less attention than their flashy jet cousins, turboshaft engines hold a specialized niche in the aviation industry. Built to be compact, efficient, and powerful, turboshafts have made modern helicopters and the feats they accomplish possible. First implemented in the 1950s, turboshaft geometry has gone largely unchanged, but advances in materials and axial flow technology have continued to drive higher power and efficiency from today's turboshafts. Similarly to the turbojet and fan industry, there are only a handful of big players in the market. The usual suspects - Pratt & Whitney, General Electric, and Rolls-Royce - have taken over most of the industry, but lesser known companies like Lycoming and Turbomeca still hold a footing in the Turboshaft world. Nomenclature shp = Shaft Horsepower SFC = Specific Fuel Consumption FPT = Free Power Turbine HPT = High Power Turbine Introduction & Background Turboshaft engines are very similar to a turboprop engine; in fact many turboshaft engines were created by modifying existing turboprop engines to fit the needs of the rotorcraft they propel. The most common use of turboshaft engines is in scenarios where high power and reliability are required within a small envelope of requirements for size and weight. Most helicopter, marine, and auxiliary power units applications take advantage of turboshaft configurations. In fact, the turboshaft plays a workhorse role in the aviation industry as much as it is does for industrial power generation. While conventional turbine jet propulsion is achieved through thrust generated by a hot and fast exhaust stream, turboshaft engines creates shaft power that drives one or more rotors on the vehicle. -

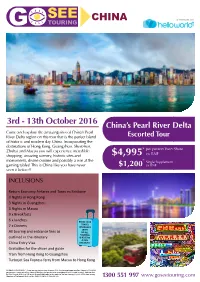

China's Pearl River Delta Escorted Tour

3rd - 13th October 2016 China’s Pearl River Delta Come and explore the amazing sites of China’s Pearl River Delta region on this tour that is the perfect blend Escorted Tour of historic and modern day China. Incorporating the destinations of Hong Kong, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, per person Twin Share Zhuhai and Macau you will experience incredible shopping, amazing scenery, historic sites and $4,995 ex BNE monuments, divine cuisine and possibly a win at the Single Supplement gaming tables! This is China like you have never $1,200 ex BNE seen it before!! BOOK YOUR TRAVEL INCLUSIONSINSURANCE WITH GO SEE Return EconomyTOURIN AirfaresG and Taxes ex Brisbane & RECEIVE A 25% 3 Nights in HongDISCOUNT Kong 3 Nights in Guangzhou 3 Nights in Macau 9 x Breakfasts 6 x lunches Book your Travel Insurance 7 x Dinners with Go See Touring All touring and entrance& fees receiv eas a 25% discount outlined in the itinerary China Entry Visa Gratuities for the driver and guide Train from Hong Kong to Guangzhou Turbojet Sea Express ferry from Macau to Hong Kong TERMS & CONDITIONS: * Prices are per person twin share in AUD. Single supplement applies. Deposit of $500.00 per person is required within 3 days of booking (unless by prior arrangement with Go See Touring), balance due by 03rd August 2016. For full terms & conditions refer to our website. Go See Touring Pty Ltd T/A Go See Touring Member of Helloworld QLD Lic No: 3198772 ABN: 72 122 522 276 1300 551 997 www.goseetouring.com Day 1 - Tuesday 04 October 2016 (L, D) Depart BNE 12:50AM Arrive HKG 7:35AM Welcome to Hong Kong!!!! After arrival enjoy a delicious Dim Sum lunch followed by an afternoon exploring the wonders of Kowloon. -

Read PDF # Articles on Aircraft Engine

[PDF] Articles On Aircraft Engine Manufacturers Of Germany, including: Bmw 801, Bmw 003, Bramo 323, Bmw... Articles On Aircraft Engine Manufacturers Of Germany, including: Bmw 801, Bmw 003, Bramo 323, Bmw 803, Bmw 802, Bmw 132, Bmw Iv, Bmw V, Bmw Vi, Bmw Iiia, Bmw Vi 5,5, Bmw Vii Book Review Definitely among the best book I have possibly read. I have study and i am sure that i will going to go through once more once more later on. Your lifestyle span is going to be convert when you full looking at this publication. (Prof. Dam on K aut zer III) A RTICLES ON A IRCRA FT ENGINE MA NUFA CTURERS OF GERMA NY, INCLUDING: BMW 801, BMW 003, BRA MO 323, BMW 803, BMW 802, BMW 132, BMW IV, BMW V, BMW V I, BMW IIIA , BMW V I 5, 5, BMW V II - To read A rticles On A ircraft Eng ine Manufacturers Of Germany, including : Bmw 801, Bmw 003, Bramo 323, Bmw 803, Bmw 802, Bmw 132, Bmw Iv, Bmw V, Bmw V i, Bmw Iiia, Bmw V i 5, 5, Bmw V ii PDF, please access the link below and download the file or have accessibility to other information which might be relevant to Articles On Aircraft Engine Manufacturers Of Germany, including: Bmw 801, Bmw 003, Bramo 323, Bmw 803, Bmw 802, Bmw 132, Bmw Iv, Bmw V, Bmw Vi, Bmw Iiia, Bmw Vi 5,5, Bmw Vii book. » Download A rticles On A ircraft Eng ine Manufacturers Of Germany, including : Bmw 801, Bmw 003, Bramo 323, Bmw 803, Bmw 802, Bmw 132, Bmw Iv, Bmw V , Bmw V i, Bmw Iiia, Bmw V i 5, 5, Bmw V ii PDF « Our professional services was launched using a aspire to serve as a complete on the web digital catalogue which offers usage of great number of PDF file e-book catalog. -

2. Afterburners

2. AFTERBURNERS 2.1 Introduction The simple gas turbine cycle can be designed to have good performance characteristics at a particular operating or design point. However, a particu lar engine does not have the capability of producing a good performance for large ranges of thrust, an inflexibility that can lead to problems when the flight program for a particular vehicle is considered. For example, many airplanes require a larger thrust during takeoff and acceleration than they do at a cruise condition. Thus, if the engine is sized for takeoff and has its design point at this condition, the engine will be too large at cruise. The vehicle performance will be penalized at cruise for the poor off-design point operation of the engine components and for the larger weight of the engine. Similar problems arise when supersonic cruise vehicles are considered. The afterburning gas turbine cycle was an early attempt to avoid some of these problems. Afterburners or augmentation devices were first added to aircraft gas turbine engines to increase their thrust during takeoff or brief periods of acceleration and supersonic flight. The devices make use of the fact that, in a gas turbine engine, the maximum gas temperature at the turbine inlet is limited by structural considerations to values less than half the adiabatic flame temperature at the stoichiometric fuel-air ratio. As a result, the gas leaving the turbine contains most of its original concentration of oxygen. This oxygen can be burned with additional fuel in a secondary combustion chamber located downstream of the turbine where temperature constraints are relaxed. -

Helicopter Turboshafts

Helicopter Turboshafts Luke Stuyvenberg University of Colorado at Boulder Department of Aerospace Engineering The application of gas turbine engines in helicopters is discussed. The work- ings of turboshafts and the history of their use in helicopters is briefly described. Ideal cycle analyses of the Boeing 502-14 and of the General Electric T64 turboshaft engine are performed. I. Introduction to Turboshafts Turboshafts are an adaptation of gas turbine technology in which the principle output is shaft power from the expansion of hot gas through the turbine, rather than thrust from the exhaust of these gases. They have found a wide variety of applications ranging from air compression to auxiliary power generation to racing boat propulsion and more. This paper, however, will focus primarily on the application of turboshaft technology to providing main power for helicopters, to achieve extended vertical flight. II. Relationship to Turbojets As a variation of the gas turbine, turboshafts are very similar to turbojets. The operating principle is identical: atmospheric gases are ingested at the inlet, compressed, mixed with fuel and combusted, then expanded through a turbine which powers the compressor. There are two key diferences which separate turboshafts from turbojets, however. Figure 1. Basic Turboshaft Operation Note the absence of a mechanical connection between the HPT and LPT. An ideal turboshaft extracts with the HPT only the power necessary to turn the compressor, and with the LPT all remaining power from the expansion process. 1 of 10 American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics A. Emphasis on Shaft Power Unlike turbojets, the primary purpose of which is to produce thrust from the expanded gases, turboshafts are intended to extract shaft horsepower (shp). -

Los Motores Aeroespaciales, A-Z

Sponsored by L’Aeroteca - BARCELONA ISBN 978-84-608-7523-9 < aeroteca.com > Depósito Legal B 9066-2016 Título: Los Motores Aeroespaciales A-Z. © Parte/Vers: 1/12 Página: 1 Autor: Ricardo Miguel Vidal Edición 2018-V12 = Rev. 01 Los Motores Aeroespaciales, A-Z (The Aerospace En- gines, A-Z) Versión 12 2018 por Ricardo Miguel Vidal * * * -MOTOR: Máquina que transforma en movimiento la energía que recibe. (sea química, eléctrica, vapor...) Sponsored by L’Aeroteca - BARCELONA ISBN 978-84-608-7523-9 Este facsímil es < aeroteca.com > Depósito Legal B 9066-2016 ORIGINAL si la Título: Los Motores Aeroespaciales A-Z. © página anterior tiene Parte/Vers: 1/12 Página: 2 el sello con tinta Autor: Ricardo Miguel Vidal VERDE Edición: 2018-V12 = Rev. 01 Presentación de la edición 2018-V12 (Incluye todas las anteriores versiones y sus Apéndices) La edición 2003 era una publicación en partes que se archiva en Binders por el propio lector (2,3,4 anillas, etc), anchos o estrechos y del color que desease durante el acopio parcial de la edición. Se entregaba por grupos de hojas impresas a una cara (edición 2003), a incluir en los Binders (archivadores). Cada hoja era sustituíble en el futuro si aparecía una nueva misma hoja ampliada o corregida. Este sistema de anillas admitia nuevas páginas con información adicional. Una hoja con adhesivos para portada y lomo identifi caba cada volumen provisional. Las tapas defi nitivas fueron metálicas, y se entregaraban con el 4 º volumen. O con la publicación completa desde el año 2005 en adelante. -Las Publicaciones -parcial y completa- están protegidas legalmente y mediante un sello de tinta especial color VERDE se identifi can los originales. -

Sir Frank Whittle

Daniel Guggenheim Medal MEDALIST FOR 1946 For pioneering the development of turbojet propulsion of aircraft. SIR FRANK WHITTLE One day in July 1942, during World War II, a slightly-built young Englishman arrived in Washington on a highly confidential mission. So important was the equipment that accompanied him, so vital its secret, that he traveled under an assumed name and many who met him knew him only as “Frank.” He was in fact Frank Whittle, then a Wing Commander in the Royal Air Force; pioneer of the turbojet engine which was destined to make one of the most pro-found changes in aircraft propulsion since the beginning of powered flight. Born in Coventry, England, on June 1, 1907, Whittle entered Leamington College at the age of 11 on a scholarship won in elementary school. At the age of 16 he entered the Royal Air Force as an aircraft apprentice in the trade of metal rigger. At the final examination he was granted a cadetship at the Royal Air Force College, Cranwell. During 1928 and 1929, as a pilot officer, he spent fifteen months in the lllth Fighter Squadron and was then assigned to a flying instructors’ course at the Central Flying School, Wittering. It was during this course that the idea of using the turbine for jet propulsion first occurred to him. His patent application was filed in January, 1930. After one year as flying instructor and eighteen months as a floatplane and catapult testpilot, he was sent to Henlow in 1932 to take the Officers Engineering Course. The summer of 1934 saw him at Cambridge University (Peterhouse). -

The New Whittle Laboratory Decarbonising Propulsion and Power

The New Whittle Laboratory Decarbonising Propulsion and Power The impressive work undertaken by the Whittle Laboratory, through the National Centre for Propulsion “and Power project, demonstrates the University’s leadership in addressing the fundamental challenges of climate change. The development of new technologies, allowing us to decarbonise air travel and power generation, will be central to our efforts to create a carbon neutral future. Professor Stephen Toope, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambridge ” 2 The New Whittle Laboratory Summary Cambridge has a long tradition of excellence in the propulsion and power sectors, which underpin aviation and energy generation. From 1934 to 1937, Frank Whittle studied engineering in Cambridge as a member of Peterhouse. During this time he was able to advance his revolutionary idea for aircraft propulsion and founded ‘Power Jets Ltd’, the company that would go on to develop the jet engine. Prior to this, in 1884 Charles Parsons of St John’s College developed the first practical steam turbine, a technology that today generates more than half of the world’s electrical power.* Over the last 50 years the Whittle Laboratory has built on this heritage, playing a crucial role in shaping the propulsion and power sectors through industry partnerships with Rolls-Royce, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and Siemens. The Whittle Laboratory is also the world’s most academically successful propulsion and power research institution, winning nine of the last 13 Gas Turbine Awards, the most prestigious prize in the field, awarded once a year since 1963. Aviation and power generation have brought many benefits – connecting people across the world and providing safe, reliable electricity to billions – but decarbonisation of these sectors is now one of society’s greatest challenges. -

A Study on the Stall Detection of an Axial Compressor Through Pressure Analysis

applied sciences Article A Study on the Stall Detection of an Axial Compressor through Pressure Analysis Haoying Chen 1,† ID , Fengyong Sun 2,†, Haibo Zhang 2,* and Wei Luo 1,† 1 Jiangsu Province Key Laboratory of Aerospace Power System, College of Energy and Power Engineering, Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, No. 29 Yudao Street, Nanjing 210016, China; [email protected] (H.C.); [email protected] (W.L.) 2 AVIC Aero-engine Control System Institute, No. 792 Liangxi Road, Wuxi 214000, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally to this work. Received: 5 June 2017; Accepted: 22 July 2017; Published: 28 July 2017 Abstract: In order to research the inherent working laws of compressors nearing stall state, a series of compressor experiments are conducted. With the help of fast Fourier transform, the amplitude–frequency characteristics of pressures at the compressor inlet, outlet and blade tip region outlet are analyzed. Meanwhile, devices imitating inlet distortion were applied in the compressor inlet distortion disturbance. The experimental results indicated that compressor blade tip region pressure showed a better performance than the compressor’s inlet and outlet pressures in regards to describing compressor characteristics. What’s more, compressor inlet distortion always disturbed the compressor pressure characteristics. Whether with inlet distortion or not, the pressure characteristics of pressure periodicity and amplitude frequency could always be maintained in compressor blade tip pressure. For the sake of compressor real-time stall detection application, a compressor stall detection algorithm is proposed to calculate the compressor pressure correlation coefficient. The algorithm also showed a good monotonicity in describing the relationship between the compressor surge margin and the pressure correlation coefficient. -

Comparative Study on Energy R&D Performance: Gas Turbine Case

Comparative Study on Energy R&D Performance: Gas Turbine Case Study Prepared by Darian Unger and Howard Herzog Massachusetts Institute of Technology Energy Laboratory Prepared for Central Research Institute of Electric Power Industry (CRIEPI) Final Report August 1998 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. INTRODUCTION/OVERVIEW .................................................................................1 2. GAS TURBINE BACKGROUND...............................................................................4 3. TECHNOLOGICAL IMPROVEMENTS .......................................................................6 4. GAS SUPPLY AND AVAILABILITY .......................................................................20 5. ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERNS ............................................................................25 6. ELECTRIC RESTRUCTURING AND CHANGING MARKET CONDITIONS ....................27 7. DRIVER INTERACTIONS .....................................................................................33 8. LESSONS FROM OTHER CASE STUDIES ................................................................39 9. CONCLUSIONS AND LESSONS.............................................................................42 APPENDIX A: TURBINE TIMELINE ..........................................................................44 APPENDIX B: REFERENCES REVIEWED ..................................................................49 APPENDIX C: EXPERTS INTERVIEWED....................................................................56 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Gas