On a New Formula: Reassessing Hooper Brewster-Jones Kate Bowan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tese Correções Defesa-23-7-16

! ALEXANDER SCRIABIN THE DEFINITION OF A NEW SOUND SPACE IN THE CRISIS OF TONALITY Luís Miguel Carvalhais Figueiredo Borges Coelho Tese apresentada à UniversidadeFiguiredo de Évora para obtenção do Grau de Doutor em Música e Musicologia Especialidade: Musicologia ORIENTADORES: Paulo de Assis Benoît Gibson ÉVORA, JULHO DE 2016 INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGAÇÃO E FORMAÇÃO AVANÇADA ALEXANDER SCRIABIN THE DEFINITION OF A NEW SOUND SPACE IN THE CRISIS OF TONALITY Luís Miguel Carvalhais Figueiredo Borges Coelho Tese apresentada à Universidade de Évora para obtenção do Grau de Doutor em Música e Musicologia Especialidade: Musicologia ORIENTADORES: Paulo de Assis Benoît Gibson ÉVORA, JULHO DE 2016 INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGAÇÃO E FORMAÇÃO AVANÇADA iii To Marta, João and Andoni, after one year of silent presence. To my parents. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to my friend Paulo de Assis, for all his dedication and encouragement in supervising my research. His enthusiasm, knowledge and always-challenging opinions were a permanent stimulus to look further. I thank Benoît Gibson for having accepted to co-supervise my work, despite my previous lack of any musicological experience. I extend my gratitude to Stanley Hanks, whose willingness to supervise my English was only limited by the small number of pages I could submit to his advice before the inexorable deadline. Thanks are also due to my former piano teachers—Amélia Vilar, Isabel Rocha, Vitaly Margulis, Dimitri Bashkirov and Galina Egyazarova—for having taught me everything I know about music. To my dear friends Catarina and André I will be always grateful: without their indefatigable assistance in the final assembling of this dissertation, my erratic relation with the writing software would have surely slipped into chaos. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2017). Michael Finnissy - The Piano Music (10 and 11) - Brochure from Conference 'Bright Futures, Dark Pasts'. This is the other version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17523/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] BRIGHT FUTURES, DARK PASTS Michael Finnissy at 70 Conference at City, University of London January 19th-20th 2017 Bright Futures, Dark Pasts Michael Finnissy at 70 After over twenty-five years sustained engagement with the music of Michael Finnissy, it is my great pleasure finally to be able to convene a conference on his work. This event should help to stimulate active dialogue between composers, performers and musicologists with an interest in Finnissy’s work, all from distinct perspectives. It is almost twenty years since the publication of Uncommon Ground: The Music of Michael Finnissy (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998). -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. ORCID: 0000-0002-0047-9379 (2021). New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices. In: McPherson, G and Davidson, J (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/25924/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices Ian Pace For publication in Gary McPherson and Jane Davidson (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), chapter 17. Introduction At the beginning of the twentieth century concert programming had transitioned away from the mid-eighteenth century norm of varied repertoire by (mostly) living composers to become weighted more heavily towards a historical and canonical repertoire of (mostly) dead composers (Weber, 2008). -

John Cage's Entanglement with the Ideas Of

JOHN CAGE’S ENTANGLEMENT WITH THE IDEAS OF COOMARASWAMY Edward James Crooks PhD University of York Music July 2011 John Cage’s Entanglement with the Ideas of Coomaraswamy by Edward Crooks Abstract The American composer John Cage was famous for the expansiveness of his thought. In particular, his borrowings from ‘Oriental philosophy’ have directed the critical and popular reception of his works. But what is the reality of such claims? In the twenty years since his death, Cage scholars have started to discover the significant gap between Cage’s presentation of theories he claimed he borrowed from India, China, and Japan, and the presentation of the same theories in the sources he referenced. The present study delves into the circumstances and contexts of Cage’s Asian influences, specifically as related to Cage’s borrowings from the British-Ceylonese art historian and metaphysician Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. In addition, Cage’s friendship with the Jungian mythologist Joseph Campbell is detailed, as are Cage’s borrowings from the theories of Jung. Particular attention is paid to the conservative ideology integral to the theories of all three thinkers. After a new analysis of the life and work of Coomaraswamy, the investigation focuses on the metaphysics of Coomaraswamy’s philosophy of art. The phrase ‘art is the imitation of nature in her manner of operation’ opens the doors to a wide- ranging exploration of the mimesis of intelligible and sensible forms. Comparing Coomaraswamy’s ‘Traditional’ idealism to Cage’s radical epistemological realism demonstrates the extent of the lack of congruity between the two thinkers. In a second chapter on Coomaraswamy, the extent of the differences between Cage and Coomaraswamy are revealed through investigating their differing approaches to rasa , the Renaissance, tradition, ‘art and life’, and museums. -

A More Attractive ‘Way of Getting Things Done’ Freedom, Collaboration and Compositional Paradox in British Improvised and Experimental Music 1965-75

A more attractive ‘way of getting things done’ freedom, collaboration and compositional paradox in British improvised and experimental music 1965-75 Simon H. Fell A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield September 2017 copyright statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. ii. Copies of this thesis, either in full or in extracts, may be made only in accordance with the regulations of the University Library. Details of these regulations may be obtained from the Librarian. This page must form part of any such copies made. iii. The ownership of any patents, designs, trade marks and any and all other intellectual property rights except for the Copyright (the “Intellectual Property Rights”) and any reproductions of copyright works, for example graphs and tables (“Reproductions”), which may be described in this thesis, may not be owned by the author and may be owned by third parties. Such Intellectual Property Rights and Reproductions cannot and must not be made available for use without the prior written permission of the owner(s) of the relevant Intellectual Property Rights and/or Reproductions. 2 abstract This thesis examines the activity of the British musicians developing a practice of freely improvised music in the mid- to late-1960s, in conjunction with that of a group of British composers and performers contemporaneously exploring experimental possibilities within composed music; it investigates how these practices overlapped and interpenetrated for a period. -

5. Calling for International Solidarity: Hanns Eisler’S Mass Songs in the Soviet Union

From Massenlieder to Massovaia Pesnia: Musical Exchanges between Communists and Socialists of Weimar Germany and the Early Soviet Union by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Bryan Gilliam, Supervisor ___________________________ Edna Andrews ___________________________ John Supko ___________________________ Jacqueline Waeber Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 i v ABSTRACT From Massenlieder to Massovaia Pesnia: Musical Exchanges between Communists and Socialists of Weimar Germany and the Early Soviet Union by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Bryan Gilliam, Supervisor ___________________________ Edna Andrews ___________________________ John Supko ___________________________ Jacqueline Waeber An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 Copyright by Yana Alexandrovna Lowry 2014 Abstract Group songs with direct political messages rose to enormous popularity during the interwar period (1918-1939), particularly in recently-defeated Germany and in the newly- established Soviet Union. This dissertation explores the musical relationship between these two troubled countries and aims to explain the similarities and differences in their approaches to collective singing. The discussion of the very complex and problematic relationship between the German left and the Soviet government sets the framework for the analysis of music. Beginning in late 1920s, as a result of Stalin’s abandonment of the international revolutionary cause, the divergences between the policies of the Soviet government and utopian aims of the German communist party can be traced in the musical propaganda of both countries. -

Copyright Page

Copyright by Michael Dylan Sailors 2013 ! The Dissertation Committee for Michael Dylan Sailors certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Manhattan by Midnight: A Suite for Jazz Orchestra in Three Movements Committee: _______________________________________ John Mills, Supervisor _______________________________________ Jeff Hellmer, Co-Supervisor _______________________________________ John Fremgen _______________________________________ Thomas O’Hare _______________________________________ Laurie Scott Young _______________________________________ Bruce Pennycook ! Manhattan by Midnight: A Suite for Jazz Orchestra in Three Movements by Michael Dylan Sailors, B. Music; M. Music Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2013 ! Dedication To my father, whose support and guidance has meant the world to me. ! Acknowledgements Special thanks to: Jeff Hellmer, John Mills and John Fremgen for their guidance and mentorship throughout my entire doctoral experience; to Duke Ellington, Thad Jones, Ed Neumeister, and Wynton Marsalis for inspiring me to compose the music found herein. ! ! v Manhattan by Midnight: A Suite for Jazz Orchestra in Three Movements Michael Dylan Sailors, D.M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2013 Supervisor: John Mills Co-Supervisor: Jeff Hellmer Manhattan by Midnight is a three-movement work for jazz orchestra -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Experimental Music: Redefining Authenticity Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3xw7m355 Author Tavolacci, Christine Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Experimental Music: Redefining Authenticity A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts in Contemporary Music Performance by Christine E. Tavolacci Committee in charge: Professor John Fonville, Chair Professor Anthony Burr Professor Lisa Porter Professor William Propp Professor Katharina Rosenberger 2017 Copyright Christine E. Tavolacci, 2017 All Rights Reserved The Dissertation of Christine E. Tavolacci is approved, and is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2017 iii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my parents, Frank J. and Christine M. Tavolacci, whose love and support are with me always. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page.……………………………………………………………………. iii Dedication………………………..…………………………………………………. iv Table of Contents………………………..…………………………………………. v List of Figures….……………………..…………………………………………….. vi AcknoWledgments….………………..…………………………...………….…….. vii Vita…………………………………………………..………………………….……. viii Abstract of Dissertation…………..………………..………………………............ ix Introduction: A Brief History and Definition of Experimental Music -

The Compositional Language of Kenny Wheeler

THE COMPOSITIONAL LANGUAGE OF KENNY WHEELER by Paul Rushka Schulich School of Music McGill University, Montreal March 2014 A paper submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of D.Mus. Performance Studies ©Paul Rushka 2014 2 ABSTRACT The roots of jazz composition are found in the canon ofthe Great American Songbook, which constitutes the majority of standard jazz repertoire and set the compositional models for jazz. Beginning in the 1960s, leading composers including Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock began stretching the boundaries set by this standard repertoire, with the goal of introducing new compositional elements in order to expand that model. Trumpeter, composer, and arranger Kenny Wheeler has been at the forefront of European jazz music since the late 1960s and his works exemplify a contemporary approach to jazz composition. This paper investigates six pieces from Wheeler's songbook and identifies the compositional elements of his language and how he has developed an original voice through the use and adaptation of these elements. In order to identify these traits, I analyzed the melodic, harmonic, structural and textural aspects of these works by studying both the scores and recordings. Each of the pieces I analyzed demonstrates qualities consistent with Wheeler's compositional style, such as the expansion oftonality through the use of mode mixture, non-functional harmonic progressions, melodic composition through intervallic sequence, use of metric changes within a song form, and structural variation. Finally, the demands of Wheeler's music on the performer are examined. 3 Resume La composition jazz est enracinee dans le Grand repertoire American de la chanson, ou "Great American Songbook", qui constitue la plus grande partie du repertoire standard de jazz, et en a defini les principes compositionnels. -

The War to End War — the Great War

GO TO MASTER INDEX OF WARFARE GIVING WAR A CHANCE, THE NEXT PHASE: THE WAR TO END WAR — THE GREAT WAR “They fight and fight and fight; they are fighting now, they fought before, and they’ll fight in the future.... So you see, you can say anything about world history.... Except one thing, that is. It cannot be said that world history is reasonable.” — Fyodor Mikhaylovich Dostoevski NOTES FROM UNDERGROUND “Fiddle-dee-dee, war, war, war, I get so bored I could scream!” —Scarlet O’Hara “Killing to end war, that’s like fucking to restore virginity.” — Vietnam-era protest poster HDT WHAT? INDEX THE WAR TO END WAR THE GREAT WAR GO TO MASTER INDEX OF WARFARE 1851 October 2, Thursday: Ferdinand Foch, believed to be the leader responsible for the Allies winning World War I, was born. October 2, Thursday: PM. Some of the white Pines on Fair Haven Hill have just reached the acme of their fall;–others have almost entirely shed their leaves, and they are scattered over the ground and the walls. The same is the state of the Pitch pines. At the Cliffs I find the wasps prolonging their short lives on the sunny rocks just as they endeavored to do at my house in the woods. It is a little hazy as I look into the west today. The shrub oaks on the terraced plain are now almost uniformly of a deep red. HDT WHAT? INDEX THE WAR TO END WAR THE GREAT WAR GO TO MASTER INDEX OF WARFARE 1914 World War I broke out in the Balkans, pitting Britain, France, Italy, Russia, Serbia, the USA, and Japan against Austria, Germany, and Turkey, because Serbians had killed the heir to the Austrian throne in Bosnia. -

Toccata Classics TOCC 0127 Notes

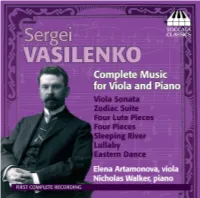

SERGEI VASILENKO AND THE VIOLA by Elena Artamonova The viola is occasionally referred to as ‘the Cinderella of instruments’ – and, indeed, it used to take a fairy godmother of a player to allow this particular Cinderella to go to the ball; the example usually cited in the liberation of the viola in a solo role is the British violist Lionel Tertis. Another musician to pay the instrument a similar honour – as a composer rather than a player – was the Russian Sergei Vasilenko (1872–1956), all of whose known compositions for viola, published and unpublished, are to be heard on this CD, the fruit of my investigations in libraries and archives in Moscow and London. None is well known; some are not even included in any of the published catalogues of Vasilenko’s music. Only the Sonata was recorded previously, first in the 1960s by Georgy Bezrukov, viola, and Anatoly Spivak, piano,1 and again in 2007 by Igor Fedotov, viola, and Leonid Vechkhayzer, piano;2 the other compositions receive their first recordings here. Sergei Nikiforovich Vasilenko had a long and distinguished career as composer, conductor and pedagogue in the first half of the twentieth century. He was born in Moscow on 30 March 1872 into an aristocratic family, whose inner circle of friends consisted of the leading writers and artists of the time, but his interest in music was rather capricious in his early childhood: he started to play piano from the age of six only to give it up a year later, although he eventually resumed his lessons. In his mid-teens, after two years of tuition on the clarinet, he likewise gave it up in favour of the oboe. -

Modal Prolongational Structure in Selected Sacred Choral

MODAL PROLONGATIONAL STRUCTURE IN SELECTED SACRED CHORAL COMPOSITIONS BY GUSTAV HOLST AND RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS by TIMOTHY PAUL FRANCIS A DISSERTATION Presented to the S!hoo" o# Mus%! and Dan!e and the Graduate S!hoo" o# the Un%'ers%ty o# Ore(on %n part%&" f$"#%""*ent o# the re+$%re*ents #or the degree o# Do!tor o# P %"oso)hy ,une 2./- DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: T%*othy P&$" Fran!%s T%t"e0 Mod&" Pro"on(ation&" Str$!ture in Se"e!ted S&!red Chor&" Co*)osit%ons by Gustav Ho"st and R&")h Vaughan W%""%&*s T %s d%ssertat%on has been ac!e)ted and ap)ro'ed in part%&" f$"#%""*ent o# the re+$%re*ents for the Do!tor o# P %"oso)hy de(ree in the S!hoo" o# Musi! and Dan!e by0 Dr1 J&!k Boss C &%r)erson Dr1 Ste) en Rod(ers Me*ber Dr1 S &ron P&$" Me*ber Dr1 Ste) en J1 Shoe*&2er Outs%de Me*ber and 3%*ber"y Andre4s Espy V%!e President for Rese&r!h & Inno'at%on6Dean o# the Gr&duate S!hoo" Or%(%n&" ap)ro'&" signatures are on f%"e w%th the Un%'ersity o# Ore(on Grad$ate S!hoo"1 Degree a4arded June 2./- %% 7-./- T%*othy Fran!%s T %s work is l%!ensed under a Creat%'e Co**ons Attr%but%on8NonCo**er!%&"8NoDer%'s 31. Un%ted States L%!ense1 %%% DISSERTATION ABSTRACT T%*othy P&$" Fran!%s Do!tor o# P %"oso)hy S!hoo" o# Musi! and Dan!e ,une 2./- T%t"e0 Mod&" Pro"on(ation&" Str$!ture in Se"e!ted S&!red Chor&" Co*)osit%ons by Gustav Ho"st and R&")h Vaughan W%""%&*s W %"e so*e co*)osers at the be(%nn%n( o# the t4entieth century dr%#ted away #ro* ton&" h%erar! %!&" str$!tures, Gustav Ho"st and R&")h Vaughan W%""%&*s sought 4ays o# integrating ton&" ideas w%th ne4 mater%&"s.