Islamist Forces, Political Reordering of Libya and Exiles in Cairo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syria: the War of Constructing Identities in the Digital Space and the Power of Discursive Practices

CONFLICT RESEARCH PROGRAMME Research at LSE Conflict Research Programme Syria: The war of constructing identities in the digital space and the power of discursive practices Bilal Zaiter About the Conflict Research Programme The Conflict Research Programme is a four-year research programme managed by the Conflict and Civil Society Research Unit at the LSE and funded by the UK Department for International Development. Our goal is to understand and analyse the nature of contemporary conflict and to identify international interventions that ‘work’ in the sense of reducing violence or contributing more broadly to the security of individuals and communities who experience conflict. About the Authors Bilal Zaiter is a Palestinian-Syrian researcher and social entrepreneur based in France. His main research interests are discursive and semiotics practices. He focuses on digital spaces and data. Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the thoughtful discussions and remarkable support of both Dr. Rim Turkmani and Sami Hadaya from the Syrian team at LSE. They showed outstanding understanding not only to the particularities of the Syrian conflict but also to what it takes to proceed with such kind of multi-methods and multi-disciplinary work. They have been patient and it was great working with them. I would also like to thank the CRP for the grant they provided to conduct this study. Without the grant this work would not have been done. Special thanks to the three Syrian programmers and IT experts who worked with me to de- velop the software needed for my master’s degree research and for this research. They are living now in France, Germany and Austria. -

Hamas's Response to the Syrian Uprising Nasrin Akhter in a Recent

Hamas’s Response to the Syrian Uprising Nasrin Akhter In a recent interview with the pro-Syrian Al Mayadeen channel based in Beirut, the Hamas deputy chief, Mousa Abu Marzouk asserted in October 2013 that Khaled Meshaal was ‘wrong’ to have raised the flag of the Syrian revolution on his historic return to Gaza at the end of last year.1 While on the face of it, Marzouk’s comment may not in itself hold much significance, referring only to the literal act of raising the flag, an inadvertent error made during an exuberant rally in which a number of other flags were also raised, subsequent remarks by Marzouk during the course of the interview describing the Syrian state as the ‘beating heart of the Palestinian cause’ and acknowledging the previous ‘favour’ of the Syrian regime towards the movement2 may be more indicative of shift in Hamas’s position of open opposition towards the Asad regime. This raises the important question of whether we are now witnessing a third phase in Hamas’s response towards the Syrian Uprising. In the first stage of its response, a period lasting from the outbreak of hostilities in the southern city of Deraa in March 2011 until December 2011, Hamas’s position appeared to be one of constructive ambiguity, publicly refraining from condemning Syrian authorities, but studiously avoiding anything which could have been interpreted as an open act of support for the Syrian regime. Such a position clearly stemmed from Hamas’s own vulnerabilities, acting with caution for fear of exacting reprisals against the movement still operating out of Damascus. -

"Al-Assad" and "Al Qaeda" (Day of CBS Interview)

This Document is Approved for Public Release A multi-disciplinary, multi-method approach to leader assessment at a distance: The case of Bashar al-Assad A Quick Look Assessment by the Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA)1 Part II: Analytical Approaches2 February 2014 Contributors: Dr. Peter Suedfeld (University of British Columbia), Mr. Bradford H. Morrison (University of British Columbia), Mr. Ryan W. Cross (University of British Columbia) Dr. Larry Kuznar (Indiana University – Purdue University, Fort Wayne), Maj Jason Spitaletta (Joint Staff J-7 & Johns Hopkins University), Dr. Kathleen Egan (CTTSO), Mr. Sean Colbath (BBN), Mr. Paul Brewer (SDL), Ms. Martha Lillie (BBN), Mr. Dana Rafter (CSIS), Dr. Randy Kluver (Texas A&M), Ms. Jacquelyn Chinn (Texas A&M), Mr. Patrick Issa (Texas A&M) Edited by: Dr. Hriar Cabayan (JS/J-38) and Dr. Nicholas Wright, MRCP PhD (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace) Copy Editor: Mr. Sam Rhem (SRC) 1 SMA provides planning support to Combatant Commands (CCMD) with complex operational imperatives requiring multi-agency, multi-disciplinary solutions that are not within core Service/Agency competency. SMA is accepted and synchronized by Joint Staff, J3, DDSAO and executed by OSD/ASD (R&E)/RSD/RRTO. 2 This is a document submitted to provide timely support to ongoing concerns as of February 2014. 1 This Document is Approved for Public Release 1 ABSTRACT This report suggests potential types of actions and messages most likely to influence and deter Bashar al-Assad from using force in the ongoing Syrian civil war. This study is based on multidisciplinary analyses of Bashar al-Assad’s speeches, and how he reacts to real events and verbal messages from external sources. -

From Cold War to Civil War: 75 Years of Russian-Syrian Relations — Aron Lund

7/2019 From Cold War to Civil War: 75 Years of Russian-Syrian Relations — Aron Lund PUBLISHED BY THE SWEDISH INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS | UI.SE Abstract The Russian-Syrian relationship turns 75 in 2019. The Soviet Union had already emerged as Syria’s main military backer in the 1950s, well before the Baath Party coup of 1963, and it maintained a close if sometimes tense partnership with President Hafez al-Assad (1970–2000). However, ties loosened fast once the Cold War ended. It was only when both Moscow and Damascus separately began to drift back into conflict with the United States in the mid-00s that the relationship was revived. Since the start of the Syrian civil war in 2011, Russia has stood by Bashar al-Assad’s embattled regime against a host of foreign and domestic enemies, most notably through its aerial intervention of 2015. Buoyed by Russian and Iranian support, the Syrian president and his supporters now control most of the population and all the major cities, although the government struggles to keep afloat economically. About one-third of the country remains under the control of Turkish-backed Sunni factions or US-backed Kurds, but deals imposed by external actors, chief among them Russia, prevent either side from moving against the other. Unless or until the foreign actors pull out, Syria is likely to remain as a half-active, half-frozen conflict, with Russia operating as the chief arbiter of its internal tensions – or trying to. This report is a companion piece to UI Paper 2/2019, Russia in the Middle East, which looks at Russia’s involvement with the Middle East more generally and discusses the regional impact of the Syria intervention.1 The present paper seeks to focus on the Russian-Syrian relationship itself through a largely chronological description of its evolution up to the present day, with additional thematically organised material on Russia’s current role in Syria. -

LIBYA CONFLICT: SITUATION UPDATE March 2011

Pro-Qaddafi Movements and Statements LIBYA CONFLICT: SITUATION UPDATE March 2011 MARCH 31: Pro-Qaddafi forces repelled a counterattack by rebels at the town of Brega. According to one report, the pro- government forces have adopted the rebel tactic of using weapon mounted pickup trucks so as to be less vulnerable to coalition airstrikes. Rebel spokesman Mustafa Gheriania stated that despite the shift in tactics, Qaddafi remains reliant on his tanks and artillery. (Guardian) MARCH 31: Government spokesman Musa Ibrahim rejected rumors that Qaddafi and his sons had fled Libya, stating that “We are still here. We will remain here until the end.” (New York Times) MARCH 31: Ali Abdussalam Treki, appointed by Qaddafi as Libya’s permanent representative to the UN, refused to accept the post, condemning the “spilling of blood” in a statement read by his nephew. (Reuters) MARCH 31: Arriving Wednesday evening in London, Libyan foreign minister Musa Kusa announced his resignation and defection from the Qaddafi regime. British Foreign Secretary William Hague cited Kusa’s defection as evidence that Qaddafi’s rule is “under pressure and crumbling from within.” Kusa is the latest senior Libyan official to have broken ranks with the Qaddafi regime. (Washington Post) MARCH 31: Calling from Misrata, rebel spokesman Sami reported that pro-Qaddafi forces resumed “artillery bombardment this morning. The pro-Qaddafi forces could not enter the town but they are surrounding it.” Reuter( s) MARCH 30: Pro-Qaddafi forces, under the cover of heavy tank and artillery fire, retook the town of Brega, forcing a rebel retreat towards Ajdabiya. (Guardian) MARCH 30: Human Rights Watch issued a statement from Benghazi asserting that pro-Qaddafi forces are laying landmines in their campaign to seize control of the country. -

Political Progress in Libya?

Political progress in Libya? Standard Note: SNIA/6582 Last updated: 10 June 2013 Author: Ben Smith Section International Affairs and Defence Section After an election in July 2012 that pleased many observers by being peaceful and largely free and fair, Libya’s progress has been slow. The interim parliament, the General National Congress, finally agreed in February 2013 on the procedure for the election of a Constituent Assembly, charged with drawing up a constitution and presenting it to the electorate for approval at a referendum. The election to the Constituent Assembly should be held some time this year. However, security problems are mounting: the official security services are still ineffectual and the void has been filled by armed militias and gangs. Grievances that built up during the dictatorship and the revolution are not being resolved and ethnic, regional and local conflicts could threaten the integrity of the country. For more detail on the outcome of the 2012 election, see the Standard Note Libya’s General Assembly election 2012, July 2012 Contents 1 Political situation 2 1.1 The Qaddafis 3 1.2 Constituent Assembly 3 2 Security 4 2.1 Bani Walid 4 2.2 Benghazi 5 2.3 NATO assistance 6 3 Christians 6 4 Migrants 6 5 The south 7 6 Economy 8 7 Refugees and the UK 8 1 Political situation Libya’s political progress since the fall of Muammar Qaddafi has been mixed. On the positive side, both local and national elections have been held with little violence. Voters surprised some observers by not following the example of neighbouring Tunisia and Egypt and electing Muslim Brotherhood supporters but electing broadly secular representatives. -

NATO’S Deceitful Libya War of Aggression: Its Meaning for Africa

NATO’s Deceitful Libya War of Aggression: Its Meaning for Africa How will history judge the West’s imperial interference By Colin Benjamin Region: sub-Saharan Africa Global Research, September 01, 2011 Theme: US NATO War Agenda Black Star News 1 September 2011 In-depth Report: NATO'S WAR ON LIBYA Since last week, Western leaders, NATO — and their friends in the puppet propaganda press, sometimes referred to as “mainstream” media—have been celebrating the usurpation of Libya into the hands of the armed insurrectionist “rebels.” But how will history judge the West’s imperial interference, in Libya, and what does this awful episode portend for other African countries? Last week, the Benghazi “rebels” advanced into Tripoli, their path paved by NATO’s bombardment of Libya’s military installations and even civilian facilities. With much of the Libyan political infrastructure now in the hands of the “rebels,” Western leaders have been gloating about their imperial intervention in toppling Colonel Muammar Quathafi’s government. Mr. Quathafi remains at large; with a million-dollar bounty on his head. Several members of the Quathafi family are now said to be in Algeria, including his wife, Safiya, daughter Aisha, and two of his sons, Mohammed and Hannibal. Many have interpreted this development as proof of Quathafi’s capitulation. Yet, Quathafi spokesman, Moussa Ibrahim has warned “We will turn Libya into a volcano of lava and fire under the feet of the invaders and their treacherous agents.” His son Seif al- Islam has also broadcast a message saying loyalists will continue to fight. Rumors are swirling around the whereabouts of the colonel. -

A Discourse Analysis of the Western-Led Intervention in Libya (2011)

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS POLÍTICAS Y SOCIOLOGÍA DEPARTAMENTO DE CIENCIA POLÍTICA Y DE LA ADMINISTRACIÓN III TESIS DOCTORAL Human rights as performance: a discourse analysis of the Western-led intervention in Libya (2011) MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTOR PRESENTADA POR Matthew Robson DIRECTOR Heriberto Cairo Carou Madrid, 2018 © Matthew Robson, 2017 PHD THESIS HUMAN RIGHTS AS PERFORMANCE: A DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF THE WESTERN-LED INTERVENTION IN LIBYA (2011) Matthew Robson Director de tesis: Heriberto Cairo Carou Departamento de Ciencia Política y de la Administración III (Teorías y Formas Políticas y Geografía Humana) Universidad Complutense de Madrid 1 Dedicated to Mum and Dad. 2 CONTENTS Acknowledgements 6 Transliteration 7 Abstract 8 Summary 9 Resúmen 13 INTRODUCTION 20 Objectives and elaboration of research questions 22 Literature review on the military intervention in Libya 26 -Concerning the legality of the NATO mission 28 -Ethical considerations 30 -The politics of Western intervention in Libya 33 Summary of Sections 48 PART 1 METHODOLOGICAL AND THEORETICAL 40 FRAMEWORK CHAPTER 1 METHODOLOGY / RESEARCH DESIGN 41 1. 1 Making choices in post-structural discourse analysis 41 1. 2 Research design for the Western-led intervention in Libya 44 CHAPTER 2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK 53 2.1 The 'critical geopolitics' research project and 'imperiality' 53 2. 2 Questions of ontology and epistemology 62 3 2.3 Discourse, power and knowledge 69 2.4 Identity, performativity and intertextuality in foreign 77 policy discourse PART 2 LIBYA IN THE WESTERN GEOPOLITICAL 97 IMAGINATION CHAPTER 3 US AND UK RELATIONS WITH LIBYA 99 DURING THE COLD WAR 3. -

'Gaddafi Son's Death'

اﻓﻐﺎﻧﺴﺘﺎن آزاد – آزاد اﻓﻐﺎﻧﺴﺘﺎن AA-AA ﭼﻮ ﮐﺸﻮر ﻧﺒﺎﺷـﺪ ﺗﻦ ﻣﻦ ﻣﺒـــــــﺎد ﺑﺪﯾﻦ ﺑﻮم وﺑﺮ زﻧﺪه ﯾﮏ ﺗﻦ ﻣــــﺒﺎد ھﻤﮫ ﺳﺮ ﺑﮫ ﺳﺮ ﺗﻦ ﺑﮫ ﮐﺸﺘﻦ دھﯿﻢ از آن ﺑﮫ ﮐﮫ ﮐﺸﻮر ﺑﮫ دﺷﻤﻦ دھﯿﻢ www.afgazad.com [email protected] زﺑﺎن ھﺎی اروﭘﺎﺋﯽ European Languages Al Jazeera Scepticism surrounds 'Gaddafi son's death' 5/12/2011 Residents in the rebel stronghold of Benghazi have taken to the streets to celebrate Libyan government's announcement of the death of Muammar Gaddafi's youngest son in an air strike, but growing scepticism remains over the veracity of the news. Gaddafi and his wife were in the Tripoli house of his 29-year-old son, Saif al-Arab Gaddafi, when it was hit by at least one missile fired by a NATO warplane late on Saturday, Libyan government spokesman Moussa Ibrahim said Sunday. Al-Arab's compound in Tripoli’s Garghour neighbourhood was attacked "with full power" in a "direct operation to assassinate the leader of this country," Ibrahim said, calling the strike a violation of international law. "What we have now is the law of the jungle," he told a news conference. "We think now it is clear to everyone that what is happening in Libya has nothing to do with the protection of civilians." Ibrahim had earlier taken journalists to the remnants of a house in Tripoli, which Libyan officials said had been hit by at least three missiles. Given the level of destruction, it is unclear that anyone could have survived. No NATO confirmation Three loud explosions were heard in Tripoli on Saturday evening as jets flew overhead. -

Hezbollah's Concept of Deterrence Vis-À-Vis Israel According to Nasrallah

Hezbollah’s Concept of Deterrence vis-à-vis Israel according to Nasrallah: From the Second Lebanon War to the Present Carmit Valensi and Yoram Schweitzer “Lebanon must have a deterrent military strength…then we will tell the Israelis to be careful. If you want to attack Lebanon to achieve goals, you will not be able to, because we are no longer a weak country. If we present the Israelis with such logic, they will think a million times.” Hassan Nasrallah, August 17, 2009 This essay deals with Hezbollah’s concept of deterrence against Israel as it developed over the ten years since the Second Lebanon War. The essay looks at the most important speeches by Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah during this period to examine the evolution and development of the concept of deterrence at four points in time that reflect Hezbollah’s internal and regional milieu (2000, 2006, 2008, and 2011). Over the years, Nasrallah has frequently utilized the media to deliver his messages and promote the organization’s agenda to key target audiences – Israel and the internal Lebanese audience. His speeches therefore constitute an opportunity for understanding the organization’s stances in general and its concept of deterrence in particular. The Quiet Decade: In the Aftermath of the Second Lebanon War, 2006-2016 I 115 Edited by Udi Dekel, Gabi Siboni, and Omer Einav 116 I Carmit Valensi and Yoram Schweitzer Principal Messages An analysis of Nasrallah’s speeches, especially since 2011, shows that he has devoted them primarily to the war in Syria and internal Lebanese politics. -

Project of Statistical Data Collection on Film and Audiovisual Markets in 9 Mediterranean Countries

Film and audiovisual data collection project EU funded Programme FILM AND AUDIOVISUAL DATA COLLECTION PROJECT PROJECT TO COLLECT DATA ON FILM AND AUDIOVISUAL PROJECT OF STATISTICAL DATA COLLECTION ON FILM AND AUDIOVISUAL MARKETS IN 9 MEDITERRANEAN COUNTRIES Country profile: 3. LEBANON EUROMED AUDIOVISUAL III / CDSU in collaboration with the EUROPEAN AUDIOVISUAL OBSERVATORY Dr. Sahar Ali, Media Expert, CDSU Euromed Audiovisual III Under the supervision of Dr. André Lange, Head of the Department for Information on Markets and Financing, European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe) Tunis, 27th February 2013 Film and audiovisual data collection project Disclaimer “The present publication was produced with the assistance of the European Union. The capacity development support unit of Euromed Audiovisual III programme is alone responsible for the content of this publication which can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union, or of the European Audiovisual Observatory or of the Council of Europe of which it is part.” The report is available on the website of the programme: www.euromedaudiovisual.net Film and audiovisual data collection project NATIONAL AUDIOVISUAL LANDSCAPE IN NINE PARTNER COUNTRIES LEBANON 1. BASIC DATA ............................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Institutions................................................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Landmarks ............................................................................................................................... -

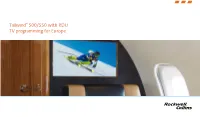

Tailwind® 500/550 with RDU TV Programming for Europe

Tailwind® 500/550 with RDU TV programming for Europe European Programming 23 CNBC Europe E 57 WDR Köln G 91 N24 Austria G 125 EinsPlus G ® for Tailwind 500/550 with RDU 24 Sonlife Broadcasting Network E 58 WDR Bielefeld G 92 rbb Berlin G 126 PHOENIX G A Arabic G German P Portuguese 25 Russia Today E 59 WDR Dortmund G 93 rbb Brandenburg G 127 SIXX G D Deutch K Korean S Spanish 26 GOD Channel E 60 WDR Düsseldorf G 94 NDR FS MV G 128 sixx Austria G E English M Multi T Turkish F French Po Polish 27 BVN TV D 61 WDR Essen G 95 NDR FS HH G 129 TELE 5 G 28 TV Record SD P 62 WDR Münster G 96 NDR FS NDS G 130 DMAX G Standard Definition Free-to-Air channel 29 TELESUR S 63 WDR Siegen G 97 NDR FS SH G 131 DMAX Austria G 30 TVGA S 64 Das Erste G 98 MDR Sachsen G 132 SPORT1 G The following channel list is effective April 21, 2016. Channels listed are subject to change 31 TBN Espana S 65 hr-fernsehen G 99 MDR S-Anhalt G 133 Eurosport 1 Deutschland G without notice. 32 TVE INTERNACIONAL EUROPA S 66 Bayerisches FS Nord G 100 MDR Thüringen G 134 Schau TV G Astra 33 CANAL 24 HORAS S 67 Bayerisches FS Süd G 101 SWR Fernsehen RP G 135 Folx TV G 34 Cubavision Internacional S 68 ARD-alpha G 102 SWR Fernsehen BW G 136 SOPHIA TV G 1 France 24 (in English) E 35 RT Esp S 69 ZDF G 103 DELUXE MUSIC G 137 Die Neue Zeit TV G 2 France 24 (en Français) F 36 Canal Algerie F 70 ZDFinfo G 104 n-tv G 138 K-TV G 3 Al Jazeera English E 37 Algerie 3 A 71 zdf_neo G 105 RTL Television G 139 a.tv G 4 NHK World TV E 38 Al Jazeera Channel A 72 zdf.kultur G 106 RTL FS G 140 TVA-OTV