Full Issue Winter 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electronic Press Kit for Laura Claridge

Electronic press kit for Laura Claridge Contact Literary Agent Carol Mann Carol Mann Agency 55 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10003 • Tel: 212 206-5635 • Fax: 212 675-4809 1 Personal Representation Dennis Oppenheimer • [email protected] • 917 650-4575 Speaking engagements / general contact • [email protected] Biography Laura Claridge has written books ranging from feminist theory to bi- ography and popular culture, most recently the story of an Ameri- can icon, Emily Post: Daughter of the Gilded Age, Mistress of Amer- ican Manners (Random House), for which she received a National Endowment for the Humanities grant. This project also received the J. Anthony Lukas Prize for a Work in Progress, administered by the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. Born in Clearwater, Florida, Laura Claridge received her Ph.D. in British Romanticism and Literary Theory from the University of Mary- land in 1986. She taught in the English departments at Converse and Wofford colleges in Spartanburg, SC, and was a tenured professor of English at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis until 1997. She has been a frequent writer and reviewer for the national press, appearing in such newspapers and magazines as The Wall Street Journal, Vogue, The Boston Globe, Los Angeles Times, and the Christian Science Monitor. Her books have been translated into Spanish, German, and Polish. She has appeared frequently in the national media, including NBC, CNN, BBC, CSPAN, and NPR and such widely watched programs as the Today Show. Laura Claridge’s biography of iconic publisher Blanche Knopf, The Lady with the Borzoi, will be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in April, 2016. -

Nieman Reports the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University

NIEMAN REPORTS THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY Vm. 60 No. 2 SuMMER 2006 Five Dollars Journalists: On the Subject of Courage 'Courage, I discovered while covering the "dirty war" in Argentina, I I I I is a relatively simple matter of ! I I overcoming fear. I realized one day that I could deal with the idea that I would be killed, simply by accepting it as a fact. The knot in my stomach loosened considerably after that. There was, after all, no reason to fear being killed once that reality had been accepted. ! I It is fear itself that makes one afraid.' I I' I' I ROBERT Cox, ON TELLING THE STORY OF THE 'DISAPPEARED' " to promote and elevate the standards of journalism" -Agnes Wahl Nieman, the benefactor of the Nieman Foundation. Vol. 60 No. 2 NIEMAN REPORTS Summer 2006 THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY Publisher Bob Giles Editor Melissa Ludtke Assistant Editor Lois Fiore Editorial Assistant Sarah Hagedorn Design Editor Diane Novetsky Nieman Reports (USPS #430-650) is published Editorial in March, June, September and December Telephone: 617-496-6308 by the Nieman Foundation at Hai-varcl University, E-Mail Address: One Francis Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138-2098. [email protected] Su bscriptions/B us iness Internet Address: 1elephone: 617-496-2968 www.nieman.ha1-vard.edu E-Mail Address: [email protected] Copyright 2006 by the President and Fellows of Ha1-vard College. Subscription $20 a year, S35 for two years; acid $10 per year for foreign airmail. Single copies S5. -

The Lady with the Borzoi: Blanche Knopf, Literary Tastemaker Extraordinaire Online

CLj9Y [Read free] The Lady with the Borzoi: Blanche Knopf, Literary Tastemaker Extraordinaire Online [CLj9Y.ebook] The Lady with the Borzoi: Blanche Knopf, Literary Tastemaker Extraordinaire Pdf Free Laura Claridge ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook #820761 in Books Laura Claridge 2016-04-12 2016-04-12Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 234.95 x 34.92 x 6.31l, 1.00 #File Name: 0374114250416 pagesThe Lady with the Borzoi Blanche Knopf Literary Tastemaker Extraordinaire | File size: 37.Mb Laura Claridge : The Lady with the Borzoi: Blanche Knopf, Literary Tastemaker Extraordinaire before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Lady with the Borzoi: Blanche Knopf, Literary Tastemaker Extraordinaire: 2 of 2 people found the following review helpful. One of America's Great Publishers at WorkBy Ronald H. ClarkBlanche Knopf (1894-1966) is the subject of this interesting biography--but it is as much a bio of Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., the publisher and the American publishing industry. Co-founder of the house in 1915, it was really Blanche who was the indefatigable spark plug whose ceaseless activity drove Knopf into the first ranks of American publishers. The book is essential reading for anyone interested in the development of American publishing during the first two-thirds of the 20th century. Given the enormous range of important books published by Knopf, the book also provides a very interesting mini-history of much of the important literature during this period and its key writers. For example, BK was a great friend of Henry Mencken as well as publisher of his classic "The American Language;" so the reader learns a good deal about this fascinating character. -

A Grace Paley Reader Stories, Essays, and Poetry Grace Paley; Edited by Kevin Bowen and Nora Paley; Introduction by George Saunders

Universal Harvester A Novel John Darnielle Life in a small town takes a dark turn when mysterious footage begins appearing on VHS cassettes at the local Video Hut Jeremy works at the counter of Video Hut in Nevada, Iowa. It’s a small town—the first “a” in the name is pronounced ay—smack in the center of the state. This is the late 1990s, pre-DVD, and the Hollywood Video in Ames poses an existential threat to Video Hut. But there are regular customers, a predictable rush in the late afternoon. It’s good enough for Jeremy: It’s a job; it’s quiet and regular; he gets to watch movies; he likes the owner, Sarah Jane; it gets him out of the house, where he and his dad try to avoid missing Mom, who died six years ago in a car wreck. FICTION But when Stephanie Parsons, a local schoolteacher, comes in to return Farrar, Straus and Giroux | 2/7/2017 her copy of Targets, starring Boris Karloff—an old movie, one Jeremy 9780374282103 | $25.00 Hardcover | 224 pages himself had ordered for the store—she has an odd complaint: “There’s Carton Qty: 24 | 8.3 in H | 5.5 in W something on it,” she says, but doesn’t elaborate. Two days later, Lindsey Brit., trans., 1st ser., audio: FSG Redinius brings back She’s All That, a new release, and complains that Dram.: The Gernert Company there’s something wrong with it: “There’s another movie on this tape.” MARKETING So Jeremy takes a look. -

March 2016 Archive

Share this: March 2016 | Volume 11 | Number 1 Now Is the Time… to Register From the Editor The generosity of BIO members for the 2016 BIO Conference when it comes to stepping up and helping out is one of the most gratifying things for me here at TBC. When I put out a call for assistance, people respond. Case in point: This month different organizations in New York are offering programs of interest to biographers that I would like to cover in the April issue. Our dedicated and intrepid NYC correspondent, Dona Munker, would attend all of them if she could, but logistics make it impossible. At BIO board member open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com Will Swift’s suggestion (thanks, Will!), I sent out an email to members in and around the city seeking aid. In less than 24 hours, I had two new reporters on board and back-ups if necessary. A big The Richmond Marriott Downtown is the site of events for Saturday, June 4, and thank you to them, as well as to within walking distance of the Library of Virginia, where the previous evening's the other writers who donate reception will be held. their time and expertise to TBC and every facet of BIO. Topping the list of volunteers If you’ve been putting off registering for the 2016 BIO Conference on June 3–5, who make BIO the thriving we strongly suggest you do it now, before the early-bird registration fee expires. -

Picture of a Life: Philip Short Explores the Biographer's Craft

Share this: July 2014 | Volume 9 | Number 5 Picture of a Life: Philip Short Explores the Biographer’s Craft More than four decades ago, while working as a freelance journalist in Malawi, Philip Short received a letter from Penguin: Would he be interested in writing a biography of Malawian president Hastings Banda, for the From the Editor publisher’s series Political Giants of the Someone is already handicapping 20th Century? Short readily agreed, the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for adding now, “I suspect they had no biography or autobiography? I was idea that I was then 23 years old!” taken aback when I saw a post at Since that auspicious start, Short Biographile weighing the chances As a newspaper journalist and BBC has a made his mark writing of Hillary Clinton’s Hard Choices copping that honor next year. correspondent, Short reported from biographies of world leaders. His most One, it’s a little early for that, no? Moscow, China, and Washington D.C. recent book, Mitterand: A Study in Two, I have a bias toward wanting Ambiguity, was published in the UK last the honor to go to a biography, fall and in April in the United States. With all his biographies, and with his next not a memoir. And three, as project on Russian leader Vladimir Putin, Short has chosen to focus on figures member Steve Weinberg explains outside the Anglo-American sphere. TBC interviewed Short to get his perspective in this issue, trying to figure out which books get nominated on what challenges that poses, and his general views of the craft of biography. -

July Issue Of

Share this: July 2015 | Volume 10 | Number 5 Lee’s Biography of We're Here Penelope Fitzgerald to Help Need help tracking down a Wins Plutarch Award source for your biography or have another question related to the craft? This month we begin Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life offering a new service: by Hermione Lee won the Author’s Queries. Our first Plutarch Award for best comes from BIO Vice biography of 2014, as President Cathy Curtis: selected by members of Does anyone have contact Biographers International information for the Knopf editor Organization. The winning who dealt with Elaine de open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com who dealt with Elaine de book was announced at the Kooning’s autobiography Sixth Annual BIO Conference proposal in the late 1980s, or, in Washington, DC. failing that, for Knopf editors “I am absolutely delighted Among Lee's other books is Biography: A Very who were employed by the to have been awarded this Short Introduction. publisher at that time? prize, especially when I look at the competition!” said If you can answer this question Dame Hermione Lee when she heard the news. President of Wolfson College, or have a query of your own, Oxford, England, Lee was not present at the announcement of the winner. let us know. The three Plutarch finalists were: The Lost Lives of the Daughters of Nicholas and Alexandria by Helen Rappaport The Mantle of Command: FDR at War, 1941-1942 by Nigel Hamilton From the Editor Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh by John Lahr From the preconference research Named after the ancient Greek biographer, the prize is the genre’s equivalent of orientations to the awarding of the third Plutarch Award, the the Oscar, in that BIO members chose the winner by secret ballot from nominees annual BIO conference last month selected by a committee of distinguished members of the craft. -

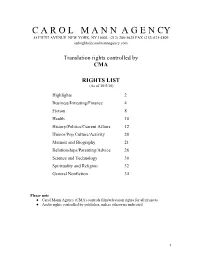

C a R O L M a N N a G E N Cy

C A R O L M A N N A G E N CY 55 FIFTH AVENUE NEW YORK, NY 10003 (212) 206-5635 FAX (212) 675-4809 [email protected] Translation rights controlled by CMA RIGHTS LIST (As of 10/5/16) Highlights 2 Business/Investing/Finance 4 Fiction 8 Health 10 History/Politics/Current Affairs 12 Humor/Pop Culture/Activity 20 Memoir and Biography 21 Relationships/Parenting/Advice 26 Science and Technology 30 Spirituality and Religion 32 General Nonfiction 34 Please note ● Carol Mann Agency (CMA) controls film/television rights for all projects ● Audio rights controlled by publisher, unless otherwise indicated 1 Highlights Paul Auster’s greatest, most heartbreaking and satisfying novel―a sweeping and surprising story of birthright and possibility, of love and of life itself: a masterpiece. Nearly two weeks early, on March 3, 1947, in the maternity ward of Beth Israel Hospital in Newark, New Jersey, Archibald Isaac Ferguson, the one and only child of Rose and Stanley Ferguson, is born. From that single beginning, Ferguson’s life will take four simultaneous and independent fictional paths. Four identical Fergusons made of the same DNA, four boys who are the same boy, go on to lead four parallel and entirely different lives. Family fortunes diverge. Athletic skills and sex lives and friendships and intellectual passions contrast. Each Henry Holt Ferguson falls under the spell of the magnificent Amy January 31st 2017 Schneiderman, yet each Amy and each Ferguson have a relationship like no other. Meanwhile, readers will take in each Ferguson’s pleasures and ache from each Ferguson’s pains, as the mortal plot of each Ferguson’s life rushes on. -

Exploring Religious Iconography in America, 1944-1950 Rebecca A

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2007 Life, Rockwell, and Radio: exploring religious iconography in America, 1944-1950 Rebecca A. Koerselman Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the American Studies Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Mass Communication Commons, Other History Commons, Religion Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Koerselman, Rebecca A., "Life, Rockwell, and Radio: exploring religious iconography in America, 1944-1950" (2007). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 14539. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/14539 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Life, Rockwell, and Radio: exploring religious iconography in America, 1944- 1950 by Rebecca A. Koerselman A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: History Program of Study Committee: Charles Dobbs, Major Professor Katherine Mellen Charron Kimberly Conger Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2007 Copyright © Rebecca A. Koerselman, 2007. All rights reserved. UMI Number: 1443072 UMI Microform 1443072