The Eidophusikon and Spring Gardens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Admiralty Arch, Commissioned

RAFAEL SERRANO Beyond Indulgence THE MAN WHO BOUGHT THE ARCH commissioned We produced a video of how the building will look once restored and by Edward VII in why we would be better than the other bidders. We explained how Admiralty Arch, memory of his mother, Queen Victoria, and designed by Sir Aston the new hotel will look within London and how it would compete Webb, is an architectural feat and one of the most iconic buildings against other iconic hotels in the capital. in London. Finally, we presented our record of accountability and track record. It is the gateway between Buckingham Palace and Trafalgar Square, but few of those driving through the arch come to appreciate its We assembled a team that has sterling experience and track record: harmony and elegance for the simple reason that they see very little Blair Associates Architecture, who have several landmark hotels in of it. Londoners also take it for granted to the extent that they simply London to their credit and Sir Robert McAlpine, as well as lighting, drive through without giving it further thought. design and security experts. We demonstrated we are able to put a lot of effort in the restoration of public spaces, in conservation and This is all set to change within the next two years and the man who sustainability. has taken on the challenge is financier-turned-developer Rafael I have learned two things from my investment banking days: Serrano. 1. The importance of team work. When JP Morgan was first founded When the UK coalition government resolved to introduce more they attracted the best talent available. -

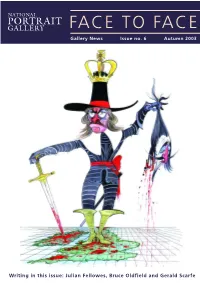

FACE to FACE Gallery News Issue No

P FACE TO FACE Gallery News Issue no. 6 Autumn 2003 Writing in this issue: Julian Fellowes, Bruce Oldfield and Gerald Scarfe FROM THE DIRECTOR The autumn exhibition Below Stairs: 400 Years of Servants’ Portraits offers an unusual opportunity to see fascinating images of those who usually remain invisible. The exhibition offers intriguing stories of the particular individuals at the centre of great houses, colleges or business institutions and reveals the admiration and affection that caused the commissioning of a portrait or photograph. We are also celebrating the completion of the new scheme for Trafalgar Square with the young people’s education project and exhibition, Circling the Square, which features photographs that record the moments when the Square has acted as a touchstone in history – politicians, activists, philosophers and film stars have all been photographed in the Square. Photographic portraits also feature in the DJs display in the Bookshop Gallery, the Terry O’Neill display in the Balcony Gallery and the Schweppes Photographic Portrait Prize launched in November in the Porter Gallery. Gerald Scarfe’s rather particular view of the men and women selected for the Portrait Gallery is published at the end of September. Heroes & Villains, is a light hearted and occasionally outrageous view of those who have made history, from Elizabeth I and Oliver Cromwell to Delia Smith and George Best. The Gallery is very grateful for the support of all of its Patrons and Members – please do encourage others to become Members and enjoy an association with us, or consider becoming a Patron, giving significant extra help to the Gallery’s work and joining a special circle of supporters. -

State Opening of Parliament State Opening of Parliament 1

State Opening of Parliament State Opening of Parliament 1 The State Opening of Parliament marks the Start of Parliament’s year start of the parliamentary year and the Queen’s The Queen’s Speech, delivered at State Opening, is the public Speech sets out the government’s agenda. statement of the government’s legislative programme for Parliament’s next working year. State Opening is the only regular occasion when the three constituent parts of Parliament that have to give their assent to new laws – the Sovereign, the House of Lords and the House of Commons – meet. The Speech is written by the government and read out in the House of Lords. Parliamentary year Queen’s Speech A ‘parliament’ runs from one general Members of both Houses and guests election to the next (five years). It is including judges, ambassadors and high broken up into sessions which run for commissioners gather in the Lords about a year – the ‘parliamentary year’. chamber for the speech. Many wear national or ceremonial dress.The Lord State Opening takes place on the first Chancellor gives the speech to the day of a new session. The Queen’s Queen who reads it out from the Speech marks the formal start to the Throne (right and see diagram on year. Neither House can conduct any page 4). business until after it has been read. Setting the agenda The speech is central to the State Contents Opening ceremony because it sets out the government’s legislative agenda Start of Parliament’s year 1 for the year. The final words, ‘Other Buckingham Palace to the House of Lords 2 measures will be laid before you’, give How it happens 4 the government flexibility to introduce Back to work 5 other bills (draft laws). -

Secret Side of London Scavenger Hunt

Secret Side of London Scavenger Hunt What better way to celebrate The Senior Section Spectacular than by exploring one of the greatest cities in the world! London is full of interesting places, monuments and fascinating museums, many of which are undiscovered by visitors to our capital city. This scavenger hunt is all about exploring a side to London you might never have seen before… (all these places are free to visit!) There are 100 Quests - how many can you complete and how many points can you earn? You will need to plan your own route – it will not be possible to complete all the challenges set in one day, but the idea is to choose parts of London you want to explore and complete as many quests as possible. Read through the whole resource before starting out, as there are many quests to choose from and bonus points to earn… Have a great day! The Secret Side of London Scavenger Hunt resource was put together by a team of Senior Section leaders in Hampshire North to celebrate The Senior Section Spectacular in 2016. As a county, we used this resource as part of a centenary event with teams of Senior Section from across the county all taking part on the same day. We hope this resource might inspire other similar events or maybe just as a way to explore London on a unit day trip…its up to you! If you would like a badge to mark taking part in this challenge, you can order a Hampshire North County badge designed by members of The Senior Section to celebrate the centenary (see photo below). -

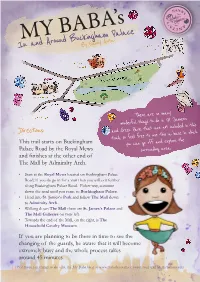

In and Around Buckingham Palace

MY BABA’s In and Around BuckinghamBy Nanny Anita Palace There are so many wonderful things to do in St. James’s Directions: and Green Park that are not included in this trail, so feel free to use this a base in which This trail starts on Buckingham you can go off and explore the Palace Road by the Royal Mews surrounding area. and finishes at the other end of The Mall by Admiralty Arch. • Start at the Royal Mews located on Buckingham Palace Road; if you do go in for a visit then you will exit further along Buckingham Palace Road. Either way, continue down the road until you come to Buckingham Palace. • Head into St. James’s Park and follow The Mall down to Admiralty Arch. • Walking down The Mall there are St. James’s Palace and The Mall Galleries on your left. • Towards the end of the Mall, on the right, is The Household Cavalry Museum. If you are planning to be there in time to see the changing of the guards, be aware that it will become extremely busy and the whole process takes around 45 minutes. For more fun things to do visit the My Baba blog at www.mybaba.com or tweet your trail @ mybabatweets INFORMATION For Attractions ATTRACTION OPENING TIMES COST February, March, November Adult 8.75 Royal Mews 10am-4pm Under 17s 5.40 April-October Under 5s free 10am-5pm Open during the sum- Adult 19.75 mer only: check their Buckingham Under 17s 11.25 website for details. Palace Under 5s free Adults 3.00 Daily 10am-5pm Mall Galleries Under 18s free April-October Adults 7.00 10am-6pm Household Calvary Child 5.00 November-March Museum Under 5s free 10am-5pm N.B Security into these attractions is very tight and you will be subject to airport style checks. -

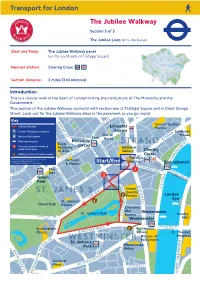

The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5

Transport for London. The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5. The Jubilee Loop (anti-clockwise). Start and finish: The Jubilee Walkway panel (on the south side of Trafalgar Square). Nearest station: Charing Cross . Section distance: 2 miles (3 kilometres). Introduction. This is a circular walk in the heart of London linking the institutions of The Monarchy and the Government. This section of the Jubilee Walkway connects with section one at Trafalgar Square and at Great George Street. Look out for the Jubilee Walkway discs in the pavement as you go round. Directions. This walk starts from Trafalgar Square. Did you know? Trafalgar Square was laid out in 1840 by Sir Charles Barry, architect of the new Houses of Parliament. The square, which is now a 'World Square', is a place for national rejoicing, celebrations and demonstrations. It is dominated by Nelson's Column with the 18-foot statue of Lord Nelson standing on top of the 171-foot column. It was erected in honour of his victory at Trafalgar. With Trafalgar Square behind you and keeping Canada House on the right, cross Cockspur Street and keep right. Go around the corner, passing the Ugandan High Commission to enter The Mall under the large stone Admiralty Arch - go through the right arch. Keep on the right-hand side of the broad avenue that is The Mall. Did you know? Admiralty Arch is the gateway between The Mall, which extends southwest, and Trafalgar Square to the northeast. The Mall was laid out as an avenue between 1660-1662 as part of Charles II's scheme for St James's Park. -

We Hope This Visual Guide Prepares You for Your Trip to Our Theatre. We

We hope this visual guide prepares you for your trip to our Theatre. We wish to show you what our building looks like, who you might meet and what you might experience during your visit. GETTING HERE Trafalgar Studios is a theatre in Central London. We have two performance spaces inside known as Studio 1 and Studio 2. Mostly plays are performed here and both children and adults come to watch them. The theatre is in an area of London called ‘the West End’. There are lots of theatres around here and it can be quite busy. This map shows where you can find us. There are many different ways to travel around London. You may arrive by train, taxi or bus. There are many famous London sights near Trafalgar Studios. For instance, you may see this statue on your way. It is called ‘Nelson’s Column’ and is found in Trafalgar Square. The road in the photo below is called Whitehall. This is the road that the theatre is on. The pavement in front of the entrance of the venue is raised by 2 steps. You can find a flat pavement on Spring Gardens, the street parallel to Whitehall. The closest train stations to the Trafalgar Studios are Charing Cross Station (4 min walk) and Waterloo Station (17 min walk via the Golden Jubilee Bridge). The closest tube stations are Charing Cross (1 min walk), then Leicester Square (8 min walk) and Westminster (9 min walk). There are also few underground car parks near the venue. See below: Q-Park Trafalgar, right next to Trafalgar Square (Spring Gardens, St. -

20171003 Forbes

10/3/2017 Exclusive: Inside The New Luxury Hotel In London's Admiralty Arch / Lifestyle / #DeLuxe OCT 3, 2017 @ 10:14 AM 32 Exclusive: Inside The New Luxury Hotel In London's Admiralty Arch Doug Gollan, CONTRIBUTOR FULL BIO Opinions expressed by Forbes Contributors are their own. Built as a monument to the British Navy and a memorial to Queen Victoria, Admiralty Arch is one of London's most notable landmarks. Gateway to The Mall, it straddles the processional route that leads to Buckingham Palace. Every time a Head of State visits the UK and goes to meet The Queen, they drive through the arch. Every time there is a Royal wedding or funeral, they drive through the Arch. For Queen Elizabeth II’s Coronation in 1953, her procession came through Admiralty Arch on the way from Westminster Abbey to Buckingham Palace (pictured below). In 2020, fully restored to its former grandeur, it will open as a 100-room luxury hotel. In an exclusive preview for Forbes.com, below are interior shots of The Mountbatten Suites, by the interior decorator David Mlinaric (the National Gallery, Royal Opera House, Victoria and Albert Museum and private clients such as Lord Rothschild and Mick Jagger). While usually, suites are the last part of the construction, in this case, the developer wanted to get to know the building and understand any challenges it might throw up. Former residents of the building include Winston Churchill (before becoming Prime Minister and moving to Downing Street) and Lord Mountbatten and his father. Future James Bond creator Ian Fleming worked as personal assistant to the Director of the Naval Intelligence Division at Admiralty Arch. -

Global Gateway London an International Center for Scholarship and Collaboration

GLOBAL GATEWAY LONDON AN INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARSHIP AND COLLABORATION WELCOME TO NOTRE DAME The University of Notre Dame boasts a network of extraordinary facilities and programs located around the world—the Notre Dame Global Gateways. Under the aegis of Notre Dame International (NDI), the Global Gateways are academic and intellectual centers where scholars, students, and leaders from universities, government, business, and the community gather to discuss issues of topical and enduring relevance. At each Global Gateway, the Notre Dame community and its many international partners and colleagues work together to advance knowledge across all disciplines with a view to the common good. London is home to one of six Notre Dame Global Gateways, with the others located in Beijing, Chicago, Dublin, Jerusalem, and Rome. The London Global Gateway consists of two major facilities: an academic center (Fischer Hall at Trafalgar Square) and a 270-bed residence building (Conway Hall, close to the South Bank near Waterloo Station). These two facilities, located in vibrant Central London, are within easy walking distance of each other. Whether for hosting a large conference or merely for providing office space for a day or two, Fischer Hall and Conway Hall serve the needs of the Notre Dame community in London. • The Summer Engineering Program in LONDON London exposes Notre Dame students to innovative technological achievements PROGRAMS during a six-week program. • The Law Summer Program is open The London Global Gateway is active to Notre Dame and non-Notre Dame year-round, hosting a myriad of activities law students and has between 30 including graduate and undergraduate and 40 participants. -

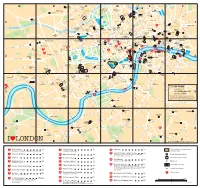

200 2 Willow Road 157 10 Downing Street 35 Abbey Road Studios 118

200 index 2 Willow Road 157 Fifty-Five 136 10 Downing Street 35 Freedom Bar 73 Guanabara 73 A Icebar 112 Abbey Road Studios 118 KOKO 137 Accessoires 75, 91, 101, 113, 129, 138, Mandarin Bar 90 Ministry of Sound 63 147, 162 Oliver’s Jazz Bar 155 Admiralty Arch 29 Portobello Star 100 Aéroports Princess Louise 83 London Gatwick Airport 171 Proud Camden 137 London Heathrow Airport 170 Purl 120 Afternoon tea 110 Salt Whisky Bar 112 Albert Memorial 88 She Soho 73 Alimentation 84, 101, 147 Shochu Lounge 83 Ambassades de Kensington Palace Simmon’s 83 Gardens 98 The Commercial Tavern 146 Antiquités 162 The Craft Beer Co. 73 Apsley House 103 The Dublin Castle 137 ArcelorMittal Orbit 166 The George Inn 63 Argent 186 The Mayor of Scaredy Cat Town 147 Artisanat 162 The Underworld 137 Auberges de jeunesse 176 Up the Creek Comedy Club 155 Vagabond 84 B Battersea Park 127 Berwick Street 68 Bank of England Museum 44 Big Ben 36 Banques 186 Bloomsbury 76 Banqueting House 34 Bond Street 108 Barbican Centre 51 Boris Bikes 185 Bars et boîtes de nuit 187 Borough Market 61 Admiral Duncan 73 Boxpark 144 Bassoon 39 Brick Lane 142 Blue Bar 90 British Library 77 BrewDog 136 Bunga Bunga 129 British Museum 80 Callooh Callay 146 Buckingham Palace 29 Cargo 146 Bus à impériale 184 Churchill Arms 100 Duke of Hamilton 162 C fabric 51 Cadeaux 39, 121, 155 http://www.guidesulysse.com/catalogue/FicheProduit.aspx?isbn=9782765826774 201 Cadogan Hall 91 Guy Fawkes Night 197 Camden Market 135 London Fashion Week 194, 196 Camden Town 130 London Film Festival 196 Cenotaph, The 35 London Marathon 194 Centres commerciaux 51, 63 London Restaurant Festival 196 Charles Dickens Museum 81 New Year’s Day Parade 194 Cheesegrater 40 New Year’s Eve Fireworks 197 Chelsea 122 Notting Hill Carnival 196 Pearly Harvest Festival 196 Chelsea Flower Show 195 Six Nations Rugby Championship 194 Chelsea Physic Garden 126 St. -

Spring Gardens, Westminster, London, SW1A

www.rib.co.uk Spring Gardens, Westminster, London, SW1A A two bedroom third and fourth floor duplex apartment situated in a beautiful period building on a quiet street adjacent to Trafalgar Square and Admiralty Arch, it is just a short walk to St James's Park. Spring Gardens is a street in London, crossing The Mall between Ad miralty Arch and Trafalgar Square. It was named after the gardens which were previously on the site, which featured a trick fountain. The gardens had been named after Sir William Spring, 2nd Baronet. Currently, the buildings in Spring Gardens include the Trafalgar Hotel, as well as the Headquarters of the British Council, and the London offices of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Located next to Charing Cross station, this apartment would work extremely well for those who need the benefits of multiple excellent transport links across the capital. Conveniently located in the heart of London's West End with easy access to a wealth of London landmarks, theatres, boutiques, restaurants and the activity of the West End and also within close proximity of St James's and Whitehall. £1,700,000 23-24 Margaret Street, London, W1W 8LF Misrepresentation Act 1967. These particulars are intended only to give a fair description of the property and do not T 020 7637 0821 F 020 7637 8827 form the basis of a contract or ay part thereof. These E [email protected] descriptions and all other information are believed to be correct but their accuracy is in no way guaranteed. -

A 1 2 3 Bcdef 4 1 2 3 4 Bcdef

F I N London C Canal H ROAD Kilburn L AD Museum Islington A BCDEE St. John’s RO F A Y High Road B Wood RT B R E B D E O L London A A Y A Zoo R D E Mornington O O C R A W St. John’s UPPER STREET Kilburn Park M IN Crescent A D E CALEDONIAN Angel D R H Kings Cross I L Wood P N D L A KINGS A I OAD A Queen’s Park M E R N British NVILL L G CROSS NTO G S D P PE V R T Library A A O Regent’s Park S G O O A CI R L Lord’s T Sadler’s Wells T N EUSTON Y N Y E V L I E RO E E Cricket B Kings Cross Theatre A R K A D N D A E K Ground . D Thameslink N ST. N C A D Y R G . PANCRAS H O D O R D A Kensal S S O R A O P R F T W Maida Vale A D A D A E G Green D O R R N T . U O R Clerkenwell E D O R E R K E T E H N W R L T R A E W Euston S A D S R E I L G N RO R U L O E W V S Euston E O Y N R O T E R A ' B G S E O N A Square ' R R AD IN H D U S D T A G 1 O O R T L 1 G O R N E L A T E A E J L N EE E A N .