London's Image and Identity Revisiting London’S Cherished Views

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Admiralty Arch, Commissioned

RAFAEL SERRANO Beyond Indulgence THE MAN WHO BOUGHT THE ARCH commissioned We produced a video of how the building will look once restored and by Edward VII in why we would be better than the other bidders. We explained how Admiralty Arch, memory of his mother, Queen Victoria, and designed by Sir Aston the new hotel will look within London and how it would compete Webb, is an architectural feat and one of the most iconic buildings against other iconic hotels in the capital. in London. Finally, we presented our record of accountability and track record. It is the gateway between Buckingham Palace and Trafalgar Square, but few of those driving through the arch come to appreciate its We assembled a team that has sterling experience and track record: harmony and elegance for the simple reason that they see very little Blair Associates Architecture, who have several landmark hotels in of it. Londoners also take it for granted to the extent that they simply London to their credit and Sir Robert McAlpine, as well as lighting, drive through without giving it further thought. design and security experts. We demonstrated we are able to put a lot of effort in the restoration of public spaces, in conservation and This is all set to change within the next two years and the man who sustainability. has taken on the challenge is financier-turned-developer Rafael I have learned two things from my investment banking days: Serrano. 1. The importance of team work. When JP Morgan was first founded When the UK coalition government resolved to introduce more they attracted the best talent available. -

Imperial War Museum Annual Report and Accounts 2019-20

Imperial War Museum Annual Report and Accounts 2019-20 Presented to Parliament pursuant to section 9(8) Museums and Galleries Act 1992 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 7 October 2020 HC 782 © Crown copyright 2020 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at: www.gov.uk/official-documents. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] ISBN 978-1-5286-1861-8 CCS0320330174 10/20 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office 2 Contents Page Annual Report 1. Introduction 4 2. Strategic Objectives 5 3. Achievements and Performance 6 4. Plans for Future Periods 23 5. Financial Review 28 6. Staff Report 31 7. Environmental Sustainability Report 35 8. Reference and Administrative Details of the Charity, 42 the Trustees and Advisers 9. Remuneration Report 47 10. Statement of Trustees’ and Director-General’s Responsibilities 53 11. Governance Statement 54 The Certificate and Report of the Comptroller and Auditor 69 General to the Houses of Parliament Consolidated Statement of Financial Activities 73 The Statement of Financial Activities 74 Consolidated and Museum Balance Sheets 75 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 76 Notes to the financial statements 77 3 1. -

Abercrombie's Green-Wedge Vision for London: the County of London Plan 1943 and the Greater London Plan 1944

Abercrombie’s green-wedge vision for London: the County of London Plan 1943 and the Greater London Plan 1944 Abstract This paper analyses the role that the green wedges idea played in the main official reconstruction plans for London, namely the County of London Plan 1943 and the Greater London Plan 1944. Green wedges were theorised in the first decade of the twentieth century and discussed in multifaceted ways up to the end of the Second World War. Despite having been prominent in many plans for London, they have been largely overlooked in planning history. This paper argues that green wedges were instrumental in these plans to the formulation of a more modern, sociable, healthier and greener peacetime London. Keywords: Green wedges, green belt, reconstruction, London, planning Introduction Green wedges have been theorised as an essential part of planning debates since the beginning of the twentieth century. Their prominent position in texts and plans rivalled that of the green belt, despite the comparatively disproportionate attention given to the latter by planning historians (see, for example, Purdom, 1945, 151; Freestone, 2003, 67–98; Ward, 2002, 172; Sutcliffe, 1981a; Amati and Yokohari, 1997, 311–37). From the mid-nineteenth century, the provision of green spaces became a fundamental aspect of modern town planning (Dümpelmann, 2005, 75; Dal Co, 1980, 141–293). In this context, the green wedges idea emerged as a solution to the need to provide open spaces for growing urban areas, as well as to establish a direct 1 connection to the countryside for inner city dwellers. Green wedges would also funnel fresh air, greenery and sunlight into the urban core. -

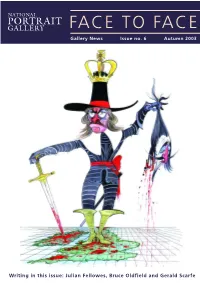

FACE to FACE Gallery News Issue No

P FACE TO FACE Gallery News Issue no. 6 Autumn 2003 Writing in this issue: Julian Fellowes, Bruce Oldfield and Gerald Scarfe FROM THE DIRECTOR The autumn exhibition Below Stairs: 400 Years of Servants’ Portraits offers an unusual opportunity to see fascinating images of those who usually remain invisible. The exhibition offers intriguing stories of the particular individuals at the centre of great houses, colleges or business institutions and reveals the admiration and affection that caused the commissioning of a portrait or photograph. We are also celebrating the completion of the new scheme for Trafalgar Square with the young people’s education project and exhibition, Circling the Square, which features photographs that record the moments when the Square has acted as a touchstone in history – politicians, activists, philosophers and film stars have all been photographed in the Square. Photographic portraits also feature in the DJs display in the Bookshop Gallery, the Terry O’Neill display in the Balcony Gallery and the Schweppes Photographic Portrait Prize launched in November in the Porter Gallery. Gerald Scarfe’s rather particular view of the men and women selected for the Portrait Gallery is published at the end of September. Heroes & Villains, is a light hearted and occasionally outrageous view of those who have made history, from Elizabeth I and Oliver Cromwell to Delia Smith and George Best. The Gallery is very grateful for the support of all of its Patrons and Members – please do encourage others to become Members and enjoy an association with us, or consider becoming a Patron, giving significant extra help to the Gallery’s work and joining a special circle of supporters. -

Greenwich Park

GREENWICH PARK CONSERVATION PLAN 2019-2029 GPR_DO_17.0 ‘Greenwich is unique - a place of pilgrimage, as increasing numbers of visitors obviously demonstrate, a place for inspiration, imagination and sheer pleasure. Majestic buildings, park, views, unseen meridian and a wealth of history form a unified whole of international importance. The maintenance and management of this great place requires sensitivity and constant care.’ ROYAL PARKS REVIEW OF GREEWNICH PARK 1995 CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD Greenwich Park is England’s oldest enclosed public park, a Grade1 listed landscape that forms two thirds of the Maritime Greenwich World Heritage Site. The parks essential character is created by its dramatic topography juxtaposed with its grand formal landscape design. Its sense of place draws on the magnificent views of sky and river, the modern docklands panorama, the City of London and the remarkable Baroque architectural ensemble which surrounds the park and its established associations with time and space. Still in its 1433 boundaries, with an ancient deer herd and a wealth of natural and historic features Greenwich Park attracts 4.7 million visitors a year which is estimated to rise to 6 million by 2030. We recognise that its capacity as an internationally significant heritage site and a treasured local space is under threat from overuse, tree diseases and a range of infrastructural problems. I am delighted to introduce this Greenwich Park Conservation Plan, developed as part of the Greenwich Park Revealed Project. The plan has been written in a new format which we hope will reflect the importance that we place on creating robust and thoughtful plans. -

H 955 Great Britain

Great Britain H 955 BACKGROUND: The heading Great Britain is used in both descriptive and subject cataloging as the conventional form for the United Kingdom, which comprises England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. This instruction sheet describes the usage of Great Britain, in contrast to England, as a subject heading. It also describes the usage of Great Britain, England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales as geographic subdivisions. 1. Great Britain vs. England as a subject heading. In general assign the subject heading Great Britain, with topical and/or form subdivisions, as appropriate, to works about the United Kingdom as a whole. Assign England, with appropriate subdivision(s), to works limited to that country. Exception: Do not use the subdivisions BHistory or BPolitics and government under England. For a work on the history, politics, or government of England, assign the heading Great Britain, subdivided as required for the work. References in the subject authority file reflect this practice. Use the subdivision BForeign relations under England only in the restricted sense described in the scope note under EnglandBForeign relations in the subject authority file. 2. Geographic subdivision. a. Great Britain. Assign Great Britain directly after topics for works that discuss the topic in relation to Great Britain as a whole. Example: Title: History of the British theatre. 650 #0 $a Theater $z Great Britain $x History. b. England, Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales. Assign England, Scotland, Northern Ireland, or Wales directly after topics for works that limit their discussion to the topic in relation to one of the four constituent countries of Great Britain. -

Thames Path Walk Section 2 North Bank Albert Bridge to Tower Bridge

Thames Path Walk With the Thames on the right, set off along the Chelsea Embankment past Section 2 north bank the plaque to Victorian engineer Sir Joseph Bazalgette, who also created the Victoria and Albert Embankments. His plan reclaimed land from the Albert Bridge to Tower Bridge river to accommodate a new road with sewers beneath - until then, sewage had drained straight into the Thames and disease was rife in the city. Carry on past the junction with Royal Hospital Road, to peek into the walled garden of the Chelsea Physic Garden. Version 1 : March 2011 The Chelsea Physic Garden was founded by the Worshipful Society of Start: Albert Bridge (TQ274776) Apothecaries in 1673 to promote the study of botany in relation to medicine, Station: Clippers from Cadogan Pier or bus known at the time as the "psychic" or healing arts. As the second-oldest stops along Chelsea Embankment botanic garden in England, it still fulfils its traditional function of scientific research and plant conservation and undertakes ‘to educate and inform’. Finish: Tower Bridge (TQ336801) Station: Clippers (St Katharine’s Pier), many bus stops, or Tower Hill or Tower Gateway tube Carry on along the embankment passed gracious riverside dwellings that line the route to reach Sir Christopher Wren’s magnificent Royal Hospital Distance: 6 miles (9.5 km) Chelsea with its famous Chelsea Pensioners in their red uniforms. Introduction: Discover central London’s most famous sights along this stretch of the River Thames. The Houses of Parliament, St Paul’s The Royal Hospital Chelsea was founded in 1682 by King Charles II for the Cathedral, Tate Modern and the Tower of London, the Thames Path links 'succour and relief of veterans broken by age and war'. -

State Opening of Parliament State Opening of Parliament 1

State Opening of Parliament State Opening of Parliament 1 The State Opening of Parliament marks the Start of Parliament’s year start of the parliamentary year and the Queen’s The Queen’s Speech, delivered at State Opening, is the public Speech sets out the government’s agenda. statement of the government’s legislative programme for Parliament’s next working year. State Opening is the only regular occasion when the three constituent parts of Parliament that have to give their assent to new laws – the Sovereign, the House of Lords and the House of Commons – meet. The Speech is written by the government and read out in the House of Lords. Parliamentary year Queen’s Speech A ‘parliament’ runs from one general Members of both Houses and guests election to the next (five years). It is including judges, ambassadors and high broken up into sessions which run for commissioners gather in the Lords about a year – the ‘parliamentary year’. chamber for the speech. Many wear national or ceremonial dress.The Lord State Opening takes place on the first Chancellor gives the speech to the day of a new session. The Queen’s Queen who reads it out from the Speech marks the formal start to the Throne (right and see diagram on year. Neither House can conduct any page 4). business until after it has been read. Setting the agenda The speech is central to the State Contents Opening ceremony because it sets out the government’s legislative agenda Start of Parliament’s year 1 for the year. The final words, ‘Other Buckingham Palace to the House of Lords 2 measures will be laid before you’, give How it happens 4 the government flexibility to introduce Back to work 5 other bills (draft laws). -

Etrvscan • Demonstrating the 7

DEVELOPMENT OF SERIF-LESS TYPE — TIMELINE SSTUVVW XYWUZa aSWbV ZSa cVUdcW ecYX IUfgh, RYiVcU MSgWV, f jcYXSaSWk Image rights and references: fcbZSUVbUlVWkSWVVc, cVbVSmVa f gVUUVc nfUVn: Røùú, Nøû. 11, 1760. ecYX ZSa Italy Fig: XVWUYc fWn ecSVWn GSYmfWWS BfUUSaUf PScfWVaS. TZV IUfgSfW fcbZSUVbUoa 1. (Left) Leonardo Agostini (1686) Le Gemme Antiche Fiurate. Engraving of a ‘Magic Gem’ of serif-less cVjdUfUSYW Zfn bYXV SWbcVfaSWkgh dWnVc fUUfbpVn ecYX FcVWbZ fcbZSUVbUa letterforms. Tav. Fig.52 [83] CARAERI MAGICI in lapis lazuli. © GIA Library Additional Collections (Gemological Institute of America), in the public domain. fWn gSUVcfch bcSUSba Ye UZV fcUa UZcYdkZYdU UZV 1750a. CgfaaSbfg RYXfW Emf. XX 1. (Right) Leonardo Agostini (1593-1669). Portrait aged 63, frontispiece from Le Gemme Antiche Fiurate, 1686. © GIA fcbZSUVbUdcV fa fW SnVfg qfa iVSWk bZfggVWkVn SW efmYdc Ye rUZV GcVVpo Library Additional Collections (Gemological Institute of America), in the public domain. 2. Dempster, Thomas (1579-1625). Coke, Thomas, Earl of qSUZSW qZfU iVbfXV pWYqW fa UZV GcfVbYlRYXfW nVifUV. Leicester, and Bounarroti, Filippo (1723). De Etruria Regali, III Libri VII, nunc primum editi curante Thomas Coke. Opus postumum. Florentiæ: Cajetanus Tartinius. Written in With some disdain he writes: “My Work ‘On the Magnificence of 1616-19. Liber Tertius, Tabulæ Eugubinæ. (viewer pp.693-702). Tabular I of V. © Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, digital.onb.ac.at in the public domain. Architecture of the Romans’ has been finished some time since... it consists 3. (Left) Forlivesi, Padre Giovanni Nicola (Giannicola). From the Convent of San Marco in Corneto. The Augustinian of 100 sheets of letterpress in Italian and Latin and of 50 plates, the IN DCCLVI GIAMBAISTA PIRANESI RELEASED monk’s 14 written bulletins to Anton Francesco Gori with observational drawings and decipherment of Etruscan inscriptions at Tarquinia near Corneto, from 11th May to 4th whole on Atlas paper. -

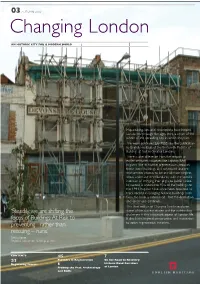

Changing London Issue 3

03 AUTUMN 2003 Changing London AN HISTORIC CITY FOR A MODERN WORLD Map-making, lists and descriptions have helped Londoners through the ages keep a sense of the whole of the sprawling city in which they live. The work continues: July 2003 saw the publication by English Heritage of the thirteenth Register of Buildings at Risk in Greater London. There is one difference from the records of earlier centuries, however.The London BAR Register, like its twelve predecessors, records those listed buildings and scheduled ancient monuments known to be at risk from neglect, decay, under-use or redundancy with the specific intention of bringing their plight to public notice. Its success is undeniable: 90% of the buildings on the 1991 Register have since been repaired. Its track record in bringing historic buildings back from the brink is established – but the dereliction and under-use continue. This third edition of Changing London explores ‘Steadily, we are shifting the some of the success stories and the outstanding challenges in this important aspect of London life. focus of Buildings At Risk to It also looks beyond conservation and restoration preventing –rather than to active regeneration initiatives. rescuing – ruins.’ Delcia Keate Regional Adviser for Buildings at Risk. CONTENTS 4/5 7 2/3 Partners in Regeneration On the Road to Recovery: Registering Success 6 Historic Road Corridors Probing the Past: Archaeology of London and BARs 03 AUTUMN 2003 REGISTERING SUCCESS Delcia Keate Regional Adviser for Buildings at Risk ‘WE CAN NOW USE THE REGISTER PROACTIVELY TO IDENTIFY EMERGING ISSUES, SO THAT SCARCE RESOURCES CAN BE DEPLOYED MORE EFFECTIVELY.’ In July English Heritage published Heritage Lottery Fund are the thirteenth edition of the commissioning a study to explore London Register of Buildings at Risk. -

The London Gazette, August 30, 1898

5216 THE LONDON GAZETTE, AUGUST 30, 1898. DISEASES OF ANIMALS ACTS, 1894 AND 1896. RETURN of OUTBREAKS of the undermentioned DISEASES for the Week ended August 27th, 1898, distinguishing Counties fincluding Boroughs*). ANTHRAX. GLANDERS (INCLUDING FARCY). County. Outbreaks Animals Animals reported. Attacked. which Animals remainec reported Oui^ Diseased during ENGLAND. No. No. County. breaks at the the reported. end of Week Northampton 2 6 the pre- as At- Notts 1 1 vious tacked. Somerset 1 1 week. Wilts 1 1 WALES. ENGLAND. No. No. No. 1 Carmarthen 1 1 London 0 15 Middlesex 1 • *• 1 Norfolk 1 SCOTLAND. Kirkcudbright 1 1 SCOTLAND. Wigtown . ... 1 1 1 1 TOTAL 8 " 12 TOTAL 10 3 17 * For convenience Berwick-upon-Tweed is considered to be in Northumberland, Dudley is con- sidered to be in Worcestershire, Stockport is considered to be in Cheshire, and the city of London ia considered to be in the county of London. ORDERS AS TO MUZZLING DOGS, Southampton. Boroughs of Portsmouth, and THE Board of Agriculture have by Order pre- Winchester (15 October, 1897). scribed, as from the dates mentioned, the Kent.—(1.) The petty sessional divisions of Muzzling of Dogs in the districts and parts of Rochester, Bearstead, Mailing, Cranbrook, Tun- districts of Local Authorities, as follows :—• bridge Wells, Tunbridge, Sevenoaks, Bromley, Berkshire.—The petty sessional divisions of and Dartford (except such portions of the petty Reading, Wokinghana, Maidenhead, and sessional divisions of Bromley and Dartford as Windsor, and the municipal borough of are subject to the provisions of the City and Maidenhead, m the county of Berks. -

Lambeth Bridge and the Location of the Southbound Bus Stop on Lambeth Palace Road Has Been Moved Back to Its Existing Location

Appendix B: Likely journey time impacts following changes to the design post consultation Summary of changes from 2017 consultation Following consultation feedback in 2017 several turning movements have now been retained eastbound onto Lambeth Bridge and the location of the southbound bus stop on Lambeth Palace Road has been moved back to its existing location. The following turning movements are now allowed at all times of day for all vehicles: Millbank North to Lambeth Bridge and Millbank South to Lambeth Bridge. The shared pedestrian and cycle areas have been reviewed and removed where it is safe for cyclists to use the carriageway. Shared use remains between Millbank South and Horseferry Road. There is also a carriageway level cycle lane through the footway between Millbank North and Lambeth Bridge. These alterations to the design in response to consultation feedback have resulted in some changes to the modelled journey times. Please note journey times are not directly comparable to the 2017 consultation. This is due to the modelled area being extended to ensure all journey times changes are captured by the modelling assessment. The tables below compare future modelled journey times with and without the Lambeth Bridge scheme. Both models include demand changes associated with committed developments and population growth, and planned changes to the road network. This allows us to isolate other changes on the network and present the predicted impact of the Lambeth Bridge scheme. 39 Revised Journey Times: Buses Future Journey Time without