Warka Water Dorze, Ethiopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Conference on Environmental Systems Technical Session Schedule As of 07/17/2005 07:40 Pm

International Conference On Environmental Systems Technical Session Schedule As of 07/17/2005 07:40 pm Monday July, 11 Integrated Ground Test Facilities: Future Exploration Missions Session Code: ICES31 Room Sala Aldobrandini Session Time: 10:00 a.m. Integrated ground test facilities for future exploration missions are critical for the development of exploration systems. This session will discuss the technology behind, systems within, design of, and operating experiences with ground based test facilities. Organizers - W. Keith Splawn, Jinny Ferl, ILC Dover Inc. Chairpersons - Phil Spampinato, ILC Dover Inc. Time Paper No. Title 9:30 a.m. BREAK 10:00 a.m. 2005-01-2756 Mars Base Zero - A Terrestrial Analog Alan E. Drysdale, Boeing Co.; Ray Collins, ISECCO 10:30 a.m. 2005-01-2757 The Environment Control System of the KM6 Horizontal Chamber Hewei Pang; Dianfu Qie, Chunyang Li, CAST 11:00 a.m. 2005-01-2759 The Combined Ground Simulation Test Technology of Thermal Vacuum for Man-Extravehicular Space Suits-Spacecraft Hewei Pang; Dianfu Qie, Chunyang Li, CAST Monday July, 11 Panel: Spin-up Habitability Design: Terrestrial Design Know-How Applied to Space Projects Session Code: ICES53 Room Sala Aldobrandini Session Time: 3:45 p.m. The design of vehicle interiors for other types of transportation may yield ideas for improving the interiors of future spacecraft and habitats. In this informal session, two specially invited speakers will discuss their work in aviation and marine fields. Architect and aircraft cabin designer Arturo Vittori will discuss approaches to the interior layout of aircraft such as the A380, the Boeing 777 and the Boeing Dreamliner, and naval architect and yacht designer Martin Francis will describe and illustrate his commissions for the design and outfitting of private yachts. -

Architecture and Vision (AV) Is an AV’S Projects Have Received International International and Multidisciplinary Team Recognition

AirTree TalisEnterprise Arturo Vittori & Andreas Vogler Vittori & Andreas Arturo © 2011 Vittori © 2011 AR CHITECTURE AN D VI SIO N ARCwww.architectureandvision.comHwww.architectureandvision.comITECTURE AND VISION COMPANY PROFILE RECOGNITION Architecture and Vision (AV) is an AV’s projects have received international international and multidisciplinary team recognition. In 2006, a prototype of the working in architecture and design, extreme environment tent, ‘DesertSeal’ engaged in the development of innovative (2004), became part of the permanent solutions and technology transfer between collection of the MoMA in New York, after diverse fields for aerospace and terrestrial being featured in SAFE: Design Takes on applications. Founded in 2003 by architects Risk (2005), curated by Paola Antonelli. Arturo Vittori and Andreas Vogler, it is based In the same year, Chicago’s Museum of in Bomarzo (Viterbo, Italy) and Munich Science and Industry (MSI) selected Vittori (Germany). The company name not only and Vogler as ‘Modern Day Leonardos’ reflects the initials of the founders, but also for its ‘Leonardo da Vinci: Man, Inventor, their conviction that architecture needs Genius’ exhibition. In 2007, a model of a vision of the future to become a long the inflatable habitat ‘MoonBaseTwo’, lasting cultural contribution of its time. developed to allow long-term exploration The vision of AV is to improve the quality of on the Moon, was acquired for the collection life through a wise use of technologies and of the MSI, while ‘MarsCruiserOne’, the available resources to create a harmonious design for a pressurized laboratory rover for integration of humans, technology and human Mars exploration, was shown at the nature. -

1 ANGELICO BOOK ARIA Bassa Risoluzione.Pdf

Atti del 4° Bio-INCONTRO ARIA_IL RESPIRO DELLA TERRA/AIR_THE EARTH BREATH Convegno Internazionale_Centro Polivalente “Frate Anselmo Caradonna” 25 maggio 2018_San Vito Lo Capo (Tp) A cura di Salvatore Cusumano e Giuseppe De Giovanni, INBAR (Istituto Nazionale di Bio-Architettura) Sezione di Trapani Comitato Scientifico Internazionale_International Scientific Committee Arch. Anna Carulli, Presidente Nazionale INBAR Arch. Salvatore Cusumano, Presidente INBAR Sez. Trapani Prof. Arch. Giuseppe De Giovanni, Presidente Comitato Scientifico INBAR Sez. Trapani, UNIPA Arch. Hendrik Müller, einszu33_Monaco (D) Prof.ssa Arch. Olimpia Niglio, Kyoto University Prof.ssa Arch. Ingrid Paoletti, Politecnico di Milano Arch. Vito Maria Mancuso, Presidente Ordine degli Architetti PPC della Provincia di Trapani Arch. Francesco Tranchida, Presidente Fondazione Architetti nel Mediterraneo “Francesco La Grassa” Segreteria Scientifica_Scientific Secreteriat Arch. Jolanda Marilù Anselmo Arch. Daniele Balsano Segreteria logistica_Logistical Secreteriat Arch. Nicola Lentini Editing Arch. Jolada Marilù Anselmo Grafic Designer Arch. Jolanda Marilù Anselmo © Copyright 2019 New Digital Frontiers srl Viale delle Scienze, Edificio 16 (c/o ARCA) 90128 Palermo www.newdigitalfrontiers.com ISBN (a stampa): 978-88-5509-016-2 ISBN (online): 978-88-5509-018-6 Patrocini_Sponsorship Università degli Studi di Palermo Dipartimento di Architettura D’ARCH Ordine degli Architetti Paesaggisti e Conservatori della Provincia di Trapani Fondazione Architetti nel Mediterraneo “Francesco La Grassa”, Trapani Collegio Provinciale dei Geometri Laureati di Trapani Con il sostegno di_With the support of: ARS (Assemblea Regionale Siciliana), Comune di San Vito Lo Capo (TP), OMER spa, Hectam srl, Giallo Macchine, Gieffe Soluzioni Edili, ETI Elettro Termo Idraulica. Indice Presentazioni Salvatore Cusumano 09 Apertura Lavori Matteo Rizzo 20 Sindaco del Comune di San Vito Lo Capo Vito Maria Mancuso 21 Presidente dell’Ordine degli Architetti P.P.C. -

3GATTI/Architecture and Vision/Atelier D/Atelier Manferdini/AWP, Alessandra Cianchetta/B+C Architectes/Barozzi / Veiga/Pietro Be

ERASMUS EFFECT 3GATTI/Architecture and Vision/Atelier D/Atelier Manferdini/AWP, Alessandra Cianchetta/B+C Architectes/Barozzi / Veiga/Pietro Belluschi/ Francesco Benelli/Lina Bo Bardi/Shumi Bose, Roberta Marcaccio/Cannatà & Fernandes/ Pippo Ciorra/Meredith Clausen/Michele Colucci/ CORREIA / RAGAZZI Arquitectos/CRISTÓBAL + MONACO arquitectos/Claudia Cucchiarato/ Abroad Italian Architects Domitilla Dardi/Delugan Meissl Associated Architects/Olivia De Oliveira, Claudia Zollinger/ Djuric-Tardio Architectes/DOSarchitects/ Durisch + Nolli Architetti/ecoLogicStudio/Peter Eisenman, Guido Zuliani/EMBT | Enric Miralles - Benedetta Tagliabue/Exposure Architects/ External Reference Architects/Fil Rouge Architetti italiani Architecture/fondaRIUS/Silvia Forlati/Fusina6/ all’estero GA Architecture/Pedro Gadanho/Vittorio Garatti/ Italian Architects Romaldo Giurgola/gravalosdimonte arquitectos/ Abroad Hans Ibelings/KOKAISTUDIOS/KUEHN MALVEZZI/ LAN Architecture/Leap/John A. Loomis/LOOP Landscape & Architecture Design/LOT-EK/MAB Marotta Basile Arquitectura/Duccio Malagamba/ Marpillero Pollak Architects/mOa mario Occhiuto architetture/MORQ*/NABITO/Sergio Nava/nbAA Nadir Bonaccorso/Caterina Padoa Schioppa/ Paratelier/Paritzki Liani Architects/Renzo Piano, Piano & Rogers/PiSaA/Stefano Rabolli Pansera/Carlo Ratti Associati/Raymond Terry Schnadelbach/Paolo Soleri/Federica Soletta/ Simone Solinas, ssa/Studio Fuksas/STUDIO RAMOPRIMO/Elisabetta Terragni + metaLAB + XYcomm/Ternullomelo Architects/ Paolo Tombesi/XCOOP EURO 28,00 ISBN 978-88-7462-604-5 In mountain regions of Ethiopia women and children walk every day for several Architecture hours to collect water from sources often unsafe that they share with animals and Vision and are at risk of contamination. To offer an alternative to this dramatic Munich, Germany situation, Architecture and Vision has designed Warka Water, a tower of 9 m WARKA WATER height that has a special fabric hanging inside to collect drinking water from Ethiopia the air by condensation. -

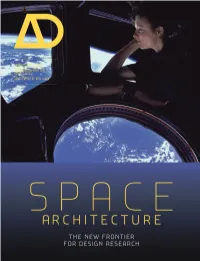

Space Architecture the New Frontier for Design Research

ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN GUEST-EDITED BY NEIL LEACH SPACE ARCHITECTURE THE NEW FRONTIER FOR DESIGN RESEARCH 06 / 2014 ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2014 ISSN 0003-8504 PROFILE NO 232 ISBN 978-1118-663301 IN THIS ISSUE 1 ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN GUEST-EDITED BY NEIL LEACH SPACE ARCHITECTURE: THE NEW FRONTIER FOR DESIGN RESEARCH 5 EDITORIAL 30 MoonCapital: Helen Castle Life on the Moon 100 Years After Apollo Andreas Vogler 6 ABOUT THE GUEST-EDITOR Neil Leach 36 Architecture For Other Planets A Scott Howe 8 INTRODUCTION Space Architecture: Th e New Frontier 40 Buzz Aldrin: Mission to Mars for Design Research Neil Leach Neil Leach 46 Colonising the Red Planet: 16 What Next for Human Space Flight? Humans to Mars in Our Time Brent Sherwood Robert Zubrin 20 Planet Moon: Th e Future of 54 Terrestrial Space Architecture Astronaut Activity and Settlement Neil Leach Madhu Th angavelu 64 Space Tourism: Waiting for Ignition Ondřej Doule 70 Alpha: From the International Style to the International Space Station Constance Adams and Rod Jones EDITORIAL BOARD Will Alsop Denise Bratton Paul Brislin Mark Burry André Chaszar Nigel Coates Peter Cook Teddy Cruz Max Fordham Massimiliano Fuksas Edwin Heathcote Michael Hensel Anthony Hunt Charles Jencks Bob Maxwell Brian McGrath Jayne Merkel Peter Murray Mark Robbins Deborah Saunt Patrik Schumacher Neil Spiller Leon van Schaik Michael Weinstock 36 Ken Yeang Alejandro Zaera-Polo 2 108 78 Being a Space Architect: 108 3D Printing in Space Astrotecture™ Projects for NASA Neil Leach Marc M Cohen 114 Astronauts Orbiting on Th eir Stomachs: 82 Outside the Terrestrial Sphere Th e Need to Design for the Consumption Greg Lynn FORM: N.O.A.H. -

30 October 2007

MoonBaseTwo 30 October 2007 20 m 36 m Index Index 2 Inspiration 3 Site 5 Design Description 9 Transportation and Configuration 11 Design Development 13 Drawings 16 Elevations 23 Illustrations 31 Model 1/100 scale 41 Exhibitions 43 Credits 48 9th International Conference on Exploration and Utilisation of the Moon MoonBaseTwo Inspiration 9th International Conference on Exploration and Utilisation of the Moon MoonBaseTwo Legacy AV packaging study 2002 Future Systems, 1985 Langley inflatable space station 1961 Kriss Kennedy NASA 1989 Werner von Braun’s Collier studies, 1953 9th International Conference on Exploration and Utilisation of the Moon MoonBaseTwo Site 9th International Conference on Exploration and Utilisation of the Moon MoonBaseTwo 9th International Conference on Exploration and Utilisation of the Moon MoonBaseTwo Distance SPACE MOON House on the Moon 0,16 G Space Station 28’000 km/h House in Orbit 0 G 400km 384’403 km Concorde 2200 km/h Jumbo Jet 17km E RE 990 km/h AC HE House SP SP 11km O TM A m 1 G 0k 10 Mount Everest 9km EARTH 9th International Conference on Exploration and Utilisation of the Moon MoonBaseTwo Moon - South Pole Moon Southpole Illumination map of Shackleton crater (circle just to the right of center). The area within the crater that receives no solar light (i.e., lies permanently in shadow) is believed to maintain a temperature of about 40 K (-233° C or -388° F). If water vapor has been deposited there, it should remain frozen at or below the surface. 9th International Conference on Exploration and Utilisation of the Moon MoonBaseTwo Design Description 9th International Conference on Exploration and Utilisation of the Moon MoonBaseTwo Description Typology: Moon base to support habitation and ‘MoonBaseTwo’ is an inflatable laboratory for In an extreme, compact environment , psy- scientific exploration. -

Curriculum Vitae | Andreas Vogler

Curriculum Vitae | Andreas Vogler Address: Hohenstaufenstrasse 10 80801 Munich, Germany mobile: +49 173 3570833 [email protected] www.architectureandvision.com Date of Birth: January 15, 1964 Place of Origin: Lungern, Switzerland Nationality: Swiss Status: Married Memberships: 1997 | Member “Deutscher Werkbund” 2002 | AIAA American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (Member of the Design Engineering Technical Committee DETC; Aerospace Architecture Subcommittee) 2002 | Bavarian Architect Chamber Education: 1999 | Accreditation courses Bavarian Architects Chamber 1994 | Graduated as Dipl. Arch. Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) Zürich, Switzerland | Diploma Work: Weather Station on Weissfluhjoch, Arosa 1992 | Rhode Island School of Design, Architecture | 1992-1993 1985 | University of Berlin (FU), Germany, Science of Theatre and Journalism | 1985-1986 1984 | University of Basel, Switzerland, French & German literature, History of Art | 1984-1985 Work: 2005 | TU Delft, The Netherlands | Research: Building Technology, Concept House Program | 06.2005-07.2006 2003 | Royal Academy of Fine Arts, School of Architecture, Copenhagen, Denmark | Guest Professor, Research Topic: The House as a Product | 04.2003-03.2005 2003 | Founded the team Architecture and Vision, with Arturo Vittori 1998 | Own office in Munich, Germany (1998 Hessische Landesvertretung Berlin competition, 2nd Prize; 1999 Hospital in Bozen, Italy, Teamwork with ITEG/Emmrich/competition 2nd stage; 1999 Biosphere BUGA 2001 Potsdam, pre selected competition; -

{DOWNLOAD} Sofia Khan Is Not Obliged 1St Edition

SOFIA KHAN IS NOT OBLIGED 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ayisha Malik | --- | --- | --- | 9781785770043 | --- | --- Laughing at Racism and Assimilation in a Novel by Ayisha Malik | Al Bawaba View all. More top stories. Bing Site Web Enter search term: Search. The results are troubling and deeply revealing Barbara Windsor was the 4ft 10in bombshell who slept with two Krays and seduced a nation. I'm a big softie! Today's headlines Most Read Meghan Markle appears on CNN to pay tribute to 'quiet heroes' of the coronavirus pandemic and the 'power of The new Age of Aquarius and what it means for you in This month Jupiter and Saturn will meet to make You are having a laugh! Chaos at the school gates as millions of London children head to classes with no idea when they will finish Kay Burley's friends 'hunt Sky News leakers who tipped off photographers about her lockdown-breaching Germany's coronavirus outbreak is 'out of control', Angela Merkel's economy minister says as country heads Britain's drivers have been hit by pothole menace even harder this year with more cars being damaged on Chaos as banks shut expats' accounts amid fears over restrictions after Brexit transition ends on January 1 Princess Beatrice is accused of flouting Covid rules by 'joining five friends for three-hour indoor dinner GPs in England will start offering Pfizer Covid jab from surgeries and town halls today - while Scottish The hell of having Covid in a long-distance marriage: For decades, rock icon Suzi Quatro's husband has lived All we want for Christmas is a supermarket -

Swiss Events

If you can't read the graphics, please download the pdf version here. SWISS EVENTS IN NEW YORK AND IN THE NORTHEASTERN PART OF THE U.S. for the period of September 12 – 26, 2012 Join us on Facebook! UPCOMING/ONGOING EVENTS Film | Music | Visual Arts | Architecture | Coming Soon | Meanwhile in Switzerland Dates, locations and ticket prices are subject to change. Please confirm before visiting events! HIGHLIGHT Thursday, September 20 FERDINAND HODLER Neue Galerie EXHIBITION OPENING 1048 Fifth Avenue New York, NY Ferdinand Hodler: View to Infinity will be the www.neuegalerie.org largest American exhibition ever devoted to this major Swiss artist. Hodler was admired by such Austrian artists as Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele, whose work is essential to the Neue Galerie collection. The organizing curator for the Neue Galerie is Jill Lloyd, a distinguished scholar who has assembled several important shows for the museum, including Van Gogh and Expressionism. The exhibition is co-organized by the Fondation Beyeler, Basel, where it will be on view from January 27 to May 26, 2013. Image: Ferdinand Hodler, Self-Portrait, 1916. FILM Saturday, September 22 TINGUELY Howard Gilman Theater 4:15pm FILM SCREENING Lincoln Center 144 West 65th Street Everything is in movement—immobility New York, NY doesn’t exist. So went the credo of Jean www.filmlinc.com Tinguely, one of the most popular, and influential, sculptors of the 20th century. This long-overdue portrait of Tinguely traces his development from his boyhood in Switzerland to his crucial stay in Paris in the early 1950s, as well as his encounters with surrealism, pop art and arte povera. -

Innovation Through Traditional Water Knowledge: an Approach to the Water Crisis

ARTICLES Innovation Through Traditional Water Knowledge: An Approach to the Water Crisis CHIARA PAPPALARDO* ABSTRACT Water supplies are being depleted and are further threatened by the impacts of climate change. The current water management systems are ill equipped to deal with the issue in signi®cant part because they do not promote distributed water collection, water conservation, and water reuse. It is critical that water laws be reformed to encourage these practices. Fortunately, a combination of often forgotten traditional water practices and more recent innovations in water use and management can help resolve this growing water crisis. These include rainwater capture, black and grey water recycling and reuse, and new advanced technologies to purify water. Stepping up these solutions through legal and regulatory change will offer local of®cials and water managers a better chance to meet present demands and future needs in an increasingly water-constrained world. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................. 629 I. The Water Challenge in The United States. ...................... 631 A. The Precarious State of Water Supply ...................... 631 1. Population Growth ................................ 631 * Doctor of Juridical Science (S.J.D.) candidate at Georgetown University Law Center. Former Research Fellow and Professional Lecturer in Law at American University Washington College of Law. LL.M., General, The George Washington University Law School 2019; LL.M. in Energy and Environmental Law, -

System Technik Funktion

WISSEN, BILDUNG, INFORMATION FÜR DIE BAUWIRTSCHAFT Erscheinungsort Perchtoldsdorf, Verlagspostamt 2380 Perchtoldsdorf. P.b.b. 02Z033056; ISSN: 1606-4550 Juli/Aug. 2010 Juli/Aug. FACHMAGAZIN www.architektur-online.com05 architektur 2010 FACHMAGAZIN 05 SYSTEM TECHNIK FUNKTION System, Technik, Funktion Undercurrent Architects ABK Architects zanderroth architekten E12,- TRIPTYQUE Albert Wimmer ZT GmbH Lang Vonier Architekten ZT GmbH Architecture and Vision Visionäres Denken mit Verantwortung Text: Beate Bartlmä MercuryHouseOne „We design with an awareness of the past, geschärft, und die Erkenntnisse werden auf TechTextil-Wettbewerb in Frankfurt entwi- for the present with a vision for the future to irdische Projekte übertragen. Technischer ckelt, und möchte den urbanen öffentlichen come. We believe, in this way architecture Wissenstransfer und Nachhaltigkeit sind Platz wieder in den Fokus als Zentrum des would not be a formal trend anymore but an hier Themen, die automatisch im Hintergrund sozialen Austausches und der Aktivitäten answer to the needs of society, for today mitwirken. Luft (Sauerstoff) und Wasser, alles stellen. Der Baldachin des Pavillons verän- through the years to come. A new understan- wird bei der Planung einer Raumkapsel genau dert seine Position in Antwort auf den Input ding of our planet as a fragile ecosystem is bedacht, da jedes zusätzliche Kilogramm an der umgebenden Umwelt, wie Sonne, Wind developing.” Gewicht auch transportiert werden muss. und die Bewegungen der Menschen. Die vier Raumkapseln, die längere Zeit unterwegs Elektromotoren werden mit Energie gespeist, „Wir entwerfen mit einem Bewusstsein für sind, sollen, gleich einem kleinen Planeten, die mittels des photovoltaischen Gewebes die Vergangenheit, für die Gegenwart mit unabhängig funktionieren. Gedanken an der Abdeckung gewonnen wird. -

4Dframe's Warka Water Workshop

Bridges Finland Conference Proceedings Modelling Environmental Problem-Solving through STEAM Activities: 4Dframe’s Warka Water Workshop Kristóf Fenyvesi (*) University of Jyväskylä, Finland Ars GEometrica Community, Experience Workshop Math-Art Movement Website: www.experienceworkshop.hu E-mail: [email protected] Ho-Gul Park (1), Taeyoung Choi (1), Kwangcheol Song (1), Seungsuk Ahn (2) 1) 4D Mathematics and Science Creativity Institute, Korea; 2) Wonkwang High School, Korea E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In this paper the Korean 4Dframe educational modelling kit’s rich capacities are presented within a STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Mathematics) education workshop. The workshop is an adaptation of the Warka Water social design project, launched by the architect Arturo Vittori in response to Ethiopia’s diminished sources of drinking water. Participants of the workshop will study the geometry of the Warka Water tower and understand its water harvesting technique, which is based on collecting water from the air. Introduction The 4Dframe educational modelling kit was developed by Ho-Gul Park, a Korean engineer and model maker originally inspired by classical, Korean architecture. 4Dframe’s concept is based upon the structural analysis and geometric formalization of building techniques utilized in the construction of Korea’s traditional, wooden buildings. 4Dframe set consists of just a small number of elegantly structured, simple module pieces. The wealth of structural variability offered by this versatile device renders it an excellent educational tool for conceptualizing, modelling, or analyzing topics relevant to all STEAM fields, such as science, technology, engineering (including robotics), arts (including architecture, or design), and mathematics [10] and relevant to these fields’ integrated pedagogical approach as well.