2001: a Space Odyssey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download This PDF File

Journal of Physics Special Topics P3_5 ALL THESE WORLDS ARE YOURS J. Bettles, I. Clarke, M. Perry and N. Pilkington. Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Leicester, Leicester, LE1 7RH. November 03, 2011 Abstract This paper investigates a plot point of the novel 2010: Odyssey Two by Arthur C. Clarke in which self replicating monoliths engulf Jupiter, increasing its density to the point when nuclear fusion can take place, giving birth to a new star. It was found that 1.629x1020 monoliths would be needed to trigger nuclear fusion in Jupiter's core, taking 136 hours to do so. Mission Profile Anomaly 1) was stated as being 11 feet tall In the second novel of Arthur C. Clarke's (3.35m) with dimensions in the exact ratio of Space Odyssey series, 2010: Odyssey Two, a 1:4:9 (the squares of the first three integers) crew was sent to discover what went wrong for depth, width and height respectively [2]. with an earlier mission to investigate a The monolith found orbiting Jupiter, monolith (figure 1) in orbit around Jupiter. designated TMA-2 (doubly inaccurate since it Shortly after they arrived, the crew were told was neither discovered in the Tycho crater to leave as “something wonderful” was going nor did it give off any magnetic signal), had to happen. The monolith disappeared from dimensions in the exact same ratio, but was orbit and a dark spot appeared on Jupiter and 718 times bigger than TMA-1 [3]. This enabled began to grow. The spot was a population of us to calculate the dimensions of TMA-2 as monoliths that were self replicating 267.5x1070x2407m with a volume of exponentially and consuming the planet. -

Up, Up, and Away by James J

www.astrosociety.org/uitc No. 34 - Spring 1996 © 1996, Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 390 Ashton Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94112. Up, Up, and Away by James J. Secosky, Bloomfield Central School and George Musser, Astronomical Society of the Pacific Want to take a tour of space? Then just flip around the channels on cable TV. Weather Channel forecasts, CNN newscasts, ESPN sportscasts: They all depend on satellites in Earth orbit. Or call your friends on Mauritius, Madagascar, or Maui: A satellite will relay your voice. Worried about the ozone hole over Antarctica or mass graves in Bosnia? Orbital outposts are keeping watch. The challenge these days is finding something that doesn't involve satellites in one way or other. And satellites are just one perk of the Space Age. Farther afield, robotic space probes have examined all the planets except Pluto, leading to a revolution in the Earth sciences -- from studies of plate tectonics to models of global warming -- now that scientists can compare our world to its planetary siblings. Over 300 people from 26 countries have gone into space, including the 24 astronauts who went on or near the Moon. Who knows how many will go in the next hundred years? In short, space travel has become a part of our lives. But what goes on behind the scenes? It turns out that satellites and spaceships depend on some of the most basic concepts of physics. So space travel isn't just fun to think about; it is a firm grounding in many of the principles that govern our world and our universe. -

The Odyssey Collection

2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C. Clarke Title: 2001: A space odyssey Author: Arthur C. Clarke Original copyright year: 1968 Epilogue copyright 1982 Foreword Behind every man now alive stand thirty ghosts, for that is the ratio by which the dead outnumber the living. Since the dawn of time, roughly a hundred billion human beings have walked the planet Earth. Now this is an interesting number, for by a curious coincidence there are approximately a hundred billion stars in our local universe, the Milky Way. So for every man who has ever lived, in this Universe there shines a star. But every one of those stars is a sun, often far more brilliant and glorious than the small, nearby star we call the Sun. And many - perhaps most - of those alien suns have planets circling them. So almost certainly there is enough land in the sky to give every member of the human species, back to the first ape-man, his own private, world-sized heaven - or hell. How many of those potential heavens and hells are now inhabited, and by what manner of creatures, we have no way of guessing; the very nearest is a million times farther away than Mars or Venus, those still remote goals of the next generation. But the barriers of distance are crumbling; one day we shall meet our equals, or our masters, among the stars. Men have been slow to face this prospect; some still hope that it may never become reality. Increasing numbers, however, are asking: "Why have such meetings not occurred already, since we ourselves are about to venture into space?" Why not, indeed? Here is one possible answer to that very reasonable question. -

Childhoods End PDF Book

CHILDHOODS END PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Arthur Charles Clarke | 218 pages | 29 Mar 1994 | Random House USA Inc | 9780345347954 | English | New York, United States Childhoods End PDF Book Old SF sometimes has a kick to it that nothing modern can quite manage. Education had overcome most of these, for a well-stocked mind is safe from boredom. Arthur C. Color: Color. Despite initial resistance and distrust from governments, the Overlords systematically eliminate disease, war, hunger, and pollution, setting the stage for the 'Golden Age of Humanity'. Tommy 2 episodes, Darius Amarfio Jefferson He was awarded the CBE in The Science Fiction Handbook. The human characters were very similar to one another. The sort of thing John Lennon imagined and no religion too. While our questions about human existence may be limited to how and why, the fact that man rules the Earth is indisputable. I do not. Books by Arthur C. By radio, Rodricks describes a vast burning column ascending from the planet. A society that was evolving to the greatest heights of artistic and progressive achievements starts to prefer apathy. Director Brian Lighthill revisited the radio adaptation proposal and obtained the rights in Sure, there are a few glimpses of its era- Childhood's End is a stone-cold Science Fiction classic. Oxford University Press. Earth transforms into a kind of utopia in a hundred years during which disease, poverty, hunger, crimes, social inequality, threat of nuclear wars are permanently eliminated thanks to the diplomacy and benevolence of the Overlords. Ricky falls ill, allegedly from exposure to poisons on the overlord ship. -

The Overlord's Burden:The Source of Sorrow in Childhood's End Matthew Candelaria

The Overlord's Burden:The Source of Sorrow in Childhood's End Matthew Candelaria In the novels of Arthur C. Clarke's most productive period, from Earthlight (1951) to Imperial Earth (1976), children appear as symbols of hope for the future. The image of the Star-Child at the end of 2001: A Space Odyssey (his collaboration with Stanley Kubrick) is imprinted on the cultural eye of humanity as we cross into the twenty-first century, and this image is emblematic of Clarke's use of children in this period. However, Clarke's most important contribution to the science-fiction genre is Childhoods End (1953), and it concludes with a very different image of children, children whose faces are "emptier than the faces of the dead," faces that contain no more feeling than that of "a snake or an insect" (Œ204). Indeed, this inverted image of children corresponds to the different mood of Childhoods End: in contrast to Clarke's other, op• timistic novels, a subtle pessimism pervades this science fiction classic. What is the source of this uncharacteristic sorrow? What shook the faith of this ardent proponent of space exploration, causing him to de• clare, "the stars are not for Man" (CE 136), even when he was chairman of the British Interplanetary Society? In assessing his reputation in the introduction to their seminal collection of essays on Clarke, Olander and Greenberg call him "a propagandist for space exploration [...] a brilliant "hard science fiction" extrapolator [...] a great mystic and modern myth-maker [...] a market-oriented, commercially motivated, and 'slick' fiction writer" (7). -

2001: a Space Odyssey by James Verniere “The a List: the National Society of Film Critics’ 100 Essential Films,” 2002

2001: A Space Odyssey By James Verniere “The A List: The National Society of Film Critics’ 100 Essential Films,” 2002 Reprinted by permission of the author Screwing with audiences’ heads was Stan- ley Kubrick’s favorite outside of chess, which is just another way of screwing with heads. One of the flaws of “Eyes Wide Shut” (1999), Kubrick’s posthumously re- leased, valedictory film, may be that it doesn’t screw with our heads enough. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), however, remains Kubrick’s crowning, confounding achievement. Homeric sci-fi film, concep- tual artwork, and dopeheads’ intergalactic Gary Lockwood and Keir Dullea try to hold a discussion away from the eyes of HAL 9000. joyride, 2001 pushed the envelope of film at Courtesy Library of Congress a time when “Mary Poppins” and “The Sound of Music” ruled the box office. 3 million years in the past and ends in the eponymous 2001 with a sequence dubbed, with a wink and nod to As technological achievement, it was a quantum leap be- the Age of Aquarius, “the ultimate trip.” In between, yond Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers serials, although it “2001: A Space Odyssey” may be more of a series of used many of the same fundamental techniques. Steven landmark sequences than a fully coherent or satisfying Spielberg called 2001 “the Big Bang” of his filmmaking experience. But its landmarks have withstood the test of generation. It was the precursor to Andrei Tarkovsky’s time and repeated parody. “Solari” (1972), Spielberg’s “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” (1977) and George Lucas’s “Star The first arrives in the wordless “Dawn of Man” episode, Wars” (1977), as well as the current digital revolution. -

Moonstruck: How Realistic Is the Moon Depicted in Classic Science Fiction Films?

MOONSTRUCK: HOW REALISTIC IS THE MOON DEPICTED IN CLASSIC SCIENCE FICTION FILMS? DONA A. JALUFKA and CHRISTIAN KOEBERL Institute of Geochemistry, University of Vienna. Althanstrasse 14, A-1090 Vienna, Austria (E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]) Abstract. Classical science fiction films have been depicting space voyages, aliens, trips to the moon, the sun, Mars, and other planets, known and unknown. While it is difficult to critique the depiction of fantastic places, or planets about which little was known at the time, the situation is different for the moon, about which a lot of facts were known from astronomical observations even at the turn of the century. Here we discuss the grade of realism with which the lunar surface has been depicted in a number of movies, beginning with George Méliès’ 1902 classic Le Voyage dans la lune and ending, just before the first manned landing on the moon, with Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Many of the movies present thoughtful details regarding the actual space travel (rockets), but none of the movies discussed here is entirely realistic in its portrayal of the lunar surface. The blunders range from obvious mistakes, such as the presence of a breathable atmosphere, or spiders and other lunar creatures, to the persistent vertical exaggeration of the height and roughness of lunar mountains. This is surprising, as the lunar topography was already well understood even early in the 20th century. 1. Introduction Since the early days of silent movies, the moon has often figured prominently in films, but mainly as a backdrop for a variety of more or (most often) less well thought-out plots. -

43759498.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Keele Research Repository This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights and duplication or sale of all or part is not permitted, except that material may be duplicated by you for research, private study, criticism/review or educational purposes. Electronic or print copies are for your own personal, non- commercial use and shall not be passed to any other individual. No quotation may be published without proper acknowledgement. For any other use, or to quote extensively from the work, permission must be obtained from the copyright holder/s. The security of the European Union’s critical outer space infrastructures Phillip A. Slann This electronic version of the thesis has been edited solely to ensure compliance with copyright legislation and excluded material is referenced in the text. The full, final, examined and awarded version of the thesis is available for consultation in hard copy via the University Library Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Relations March 2015 Keele University Abstract This thesis investigates the European Union’s (EU) conceptualisation of outer space security in the absence of clear borders or boundaries. In doing so, it analyses the means the EU undertakes to secure the space segments of its critical outer space infrastructures and the services they provide. The original contribution to knowledge offered by this thesis is the framing of European outer space security as predicated upon anticipatory mechanisms targeted towards critical outer space infrastructures. The objective of this thesis is to contribute to astropolitical literature through an analysis of the EU’s efforts to secure the space segments of its critical outer space infrastructures, alongside a conceptualisation of outer space security based upon actor-specific threats, critical infrastructures and anticipatory security measures. -

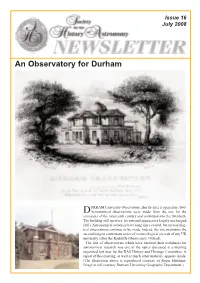

An Observatory for Durham

Issue 16 July 2008 An Observatory for Durham URHAM University Observatory, shortly after it opened in 1840. DAstronomical observations were made from the site for the remainder of the nineteenth century and continued into the twentieth. The building still survives, its external appearance largely unchanged (left). Astronomical activities have long since ceased, but meteorolog- ical observations continue to be made. Indeed, the site maintains the second longest continuous series of meteorological records of any UK university (after the Radcliffe Observatory, Oxford). The fate of observatories which have outlived their usefulness for astronomical research was one of the topics discussed at a meeting organised last year by the RAS History and Heritage Committee. A report of this meeting, as well as much other material, appears inside. (The illustration above is reproduced courtesy of Roger Hutchins. Image at left courtesy Durham University Geography Department.) Editorial Clive Davenhall ELCOME to the July 2008 widely, any topic in the history of cant impact on our discipline. Until Wissue of the Newsletter. This astronomy. We encourage you to 2007 he was the Project Manager for issue sees a return to our normal contribute. Longer contributions, the NASA Astrophysics Data fare, after the ‘Space Age Special’ of such as articles and book reviews, System (ADS) and led the small no. 15. It is also something of a also continue to be welcome, of team which developed this biblio- bumper issue, partly because of course. graphic service. From modest begin- material deferred from last time. One piece of good news, which we nings it has become a comprehen- Less happily it is also somewhat report on p7, is that the SHA’s Vice- sive on-line index of the astronomi- delayed, for which we apologise. -

ARTHUR C. CLARKE Father of Satellite Communication

K. SMILES MASCARENHAS ARTHUR C. CLARKE Father of Satellite Communication Sir Arthur C. Clarke, one of the greatest science fiction Feature Article Feature writers, will continue to shine like a bright star among the scientific greats of our time for years to come. “Prediction is very difficult, especially if it’s about the future.” A geostationary satellite is a satellite that has its revolution — Niels Bohr period equal to the earth’s rotation period. When viewed from any geographical point, it will appear to be stationary above it. HEN we see Wimbledon live, or the opening ceremony To satisfy this condition, the satellite has to orbit the earth at a of the Olympics, via satellite, we seldom remember height of 36, 000 km above the equator. Technologically, it would Wthe person who first suggested that satellites could be not have appeared feasible at that time. An orbit of 36,000 km used for communication purposes. Even when that person above the equator is officially recognized by the International entered the Glorious Abode on 19 March 2008, few TV channels Astronomical Union (IAU) as a “Clarke Orbit”, in his honour. The remembered him with gratitude. Even Science Fiction buffs who concept was published in the “Wireless World” magazine in read his novels avidly must have failed to notice the demise of a October 1945. Clarke would have made billions if he had great Scientific Prophet—Sir Arthur C. Clarke who predicted not patented his idea. But like the great Marie Curie, who refused to only communication through geostationary satellites, but also patent her discovery of Radium, Clarke’s only intention was to advances in computer technology. -

Filmografía De Arthur C. Clarke 12

2 Índice: 1. Murió Arthur C. Clarke, maestro de la Ciencia ficción. 2. Arthur C. Clarke. Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre. 3. La estrella. Arthur C. Clarke 4. El centinela. Arthur C. Clarke 5. Entrevista a Sir Arthur C. Clarke: “La Humanidad sobrevivirá a la avalancha de información” por Nalaka Gunawardene 6. La última orden. Arthur C. Clarke 7. Crimen en Marte. Arthur C. Clarke 8. Frases célebres de Arthur C. Clarke 9. Que te vaya bien mi clon. Obituario a Arthur C. Clarke. Por H2blog. 10. Los nueve mil millones de nombres de Dios. Arthur C. Clarke 11. Sección cine: Filmografía de Arthur C. Clarke 12. Historia del cine ciberpunk. 1993. New Dominion Tank Police. 8 Man Alter. Guyver 2. Robocop 3. Para descargar números anteriores de Qubit, visitar http://www.eldiletante.co.nr Para subscribirte a la revista, escribir a [email protected] 3 MURIÓ ARTHUR C. CLARKE, MAESTRO DE LA CIENCIA FICCIÓN Publicado el 21 Marzo 08 El martes 18, falleció Arthur C. Clarke. Autor del relato El centinela, que sirvió de base para el guión-novela que Stanley Kubrick llevaría al cine como 2001: Odisea del Espacio. Científico, sentó las bases para las órbitas geoestacionarias (órbita Clarke en su honor) de los satélites; en los 1960 fue comentarista para la CBS de las misiones Apolo que llevaron al hombre a la Luna en 1969. Nota de La Nación (Argentina) COLOMBO, Sri Lanka, 19/mar/08.- El escritor británico Arthur C. Clarke, cuya obra hizo aportes tanto a la ciencia ficción como a los descubrimientos científicos, falleció ayer, a los 90 años, en un hospital de la capital de Sri Lanka, donde residía desde 1956. -

A Space Odyssey

2001: A Space Odyssey Peter Krämer BFI Film Classics The BFI Film Classics is a series of books that introduces, interprets and celebrates landmarks of world cinema. Each volume offers an argument for the film’s ‘classic’ status, together with discussion of its production and reception history, its place within a genre or national cinema, an account of its technical and aesthetic importance, and in many cases, the author’s personal response to the film. For a full list of titles available in the series, please visit our website: <www.palgrave.com/bfi> ‘Magnificently concentrated examples of flowing freeform critical poetry.’ Uncut ‘A formidable body of work collectively generating some fascinating insights into the evolution of cinema.’ Times Higher Education Supplement ‘The series is a landmark in film criticism.’ Quarterly Review of Film and Video Editorial Advisory Board Geoff Andrew, British Film Institute Laura Mulvey, Birkbeck College, Edward Buscombe University of London W illiam P. Germano, The Cooper Union for Alastair Phillips , University of Warwick the Advancement of Science and Art Dana Polan, New York University Lalitha Gopalan, University of Texas at B. Ruby Rich, University of California, Austin Santa Cruz Lee Grieveson, University College London Amy Villarejo, Cornell University Nick James, Editor, Sight & Sound Zhen Zhang, New York University This page intentionally left blank 2001: A Space Odyssey Peter Krämer A BFI book published by Palgrave Macmillan © Peter Krämer 2010 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS.