Our Migrant Shorebirds in Southern South America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IOM Regional Strategy 2020-2024 South America

SOUTH AMERICA REGIONAL STRATEGY 2020–2024 IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. Publisher: International Organization for Migration Av. Santa Fe 1460, 5th floor C1060ABN Buenos Aires Argentina Tel.: +54 11 4813 3330 Email: [email protected] Website: https://robuenosaires.iom.int/ Cover photo: A Syrian family – beneficiaries of the “Syria Programme” – is welcomed by IOM staff at the Ezeiza International Airport in Buenos Aires. © IOM 2018 _____________________________________________ ISBN 978-92-9068-886-0 (PDF) © 2020 International Organization for Migration (IOM) _____________________________________________ All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. PUB2020/054/EL SOUTH AMERICA REGIONAL STRATEGY 2020–2024 FOREWORD In November 2019, the IOM Strategic Vision was presented to Member States. It reflects the Organization’s view of how it will need to develop over a five-year period, in order to effectively address complex challenges and seize the many opportunities migration offers to both migrants and society. It responds to new and emerging responsibilities – including membership in the United Nations and coordination of the United Nations Network on Migration – as we enter the Decade of Action to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. -

North America Other Continents

Arctic Ocean Europe North Asia America Atlantic Ocean Pacific Ocean Africa Pacific Ocean South Indian America Ocean Oceania Southern Ocean Antarctica LAND & WATER • The surface of the Earth is covered by approximately 71% water and 29% land. • It contains 7 continents and 5 oceans. Land Water EARTH’S HEMISPHERES • The planet Earth can be divided into four different sections or hemispheres. The Equator is an imaginary horizontal line (latitude) that divides the earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres, while the Prime Meridian is the imaginary vertical line (longitude) that divides the earth into the Eastern and Western hemispheres. • North America, Earth’s 3rd largest continent, includes 23 countries. It contains Bermuda, Canada, Mexico, the United States of America, all Caribbean and Central America countries, as well as Greenland, which is the world’s largest island. North West East LOCATION South • The continent of North America is located in both the Northern and Western hemispheres. It is surrounded by the Arctic Ocean in the north, by the Atlantic Ocean in the east, and by the Pacific Ocean in the west. • It measures 24,256,000 sq. km and takes up a little more than 16% of the land on Earth. North America 16% Other Continents 84% • North America has an approximate population of almost 529 million people, which is about 8% of the World’s total population. 92% 8% North America Other Continents • The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of Earth’s Oceans. It covers about 15% of the Earth’s total surface area and approximately 21% of its water surface area. -

Age-Related Differences in Ruddy Turnstone Foraging and Aggressive Behavior

AGE-RELATED DIFFERENCES IN RUDDY TURNSTONE FORAGING AND AGGRESSIVE BEHAVIOR SARAH GROVES ABSTRACT.--Theforaging behavior of fall migrant Ruddy Turnstoneswas studiedon the Mas- sachusettscoast on 2 different substrates,barnacle-covered rocks and sand and weed-litteredflats. Foragingrates differedsignificantly between the 2 substrates.On eachsubstrate the foragingand successrates of adults and juveniles differed significantly while the frequenciesof successwere similarfor both age-classes.The observeddifferences in foragingrates of adultsand juvenilesmay be due to the degreeof refinementof foragingtechniques. Experience in searchingfor and handling prey may be a primary factor accountingfor thesedifferences, and foragingperformance probably improves with age and experience.Alternatively, the differencesmay be due to the presenceof inefficient juveniles that do not survive to adulthood. Both adultsand juveniles in the tall-depressedposture were dominant in aggressiveinteractions much morefrequently than birds in the tall-levelposture. In mixedflocks of foragingadult and juvenile turnstones,the four possibletypes of aggressiveinteractions occurred nonrandomly. Adult over juvenile interactionsoccurred more frequently than expected,and juvenile over adult interac- tions were never seen.A tentative explanationof this phenomenonmay be that juveniles misinter- pret or respondambivalently to messagesconveyed behaviorally by adultsand thusbecome espe- cially vulnerableto aggressionby adults.The transiencyof migrantsmade it unfeasibleto evaluate -

South America Wine Cruise!

South America Wine Cruise! 17-Day Voyage Aboard Oceania Marina Santiago to Buenos Aires January 28 to February 14, 2022 Prepare to be awestruck by the magnificent wonders of South America! Sail through the stunning fjords of Patagonia and experience the cheerfully painted colonial buildings and cosmopolitan lifestyle of Uruguay and Argentina. Many people know about the fantastic Malbec, Torrontes, Tannat, and Carminiere wines that come from this area, but what they may not know is how many other great styles of wine are made by passionate winemakers throughout Latin America. This cruise will give you the chance to taste really remarkable wines from vineyards cooled by ocean breezes to those perched high in the snow-capped Andes. All made even more fun and educational by your wine host Paul Wagner! Your Exclusive Onboard Wine Experience Welcome Aboard Reception Four Exclusive Wine Paired Dinners Four Regional Wine Seminars Farewell Reception Paul Wagner Plus Enjoy: Renowned Wine Expert and Author Pre-paid Gratuities! (Expedia exclusive benefit!) "After many trips to Latin America, I want to share the wines, food and Complimentary Wine and Beer with lunch and dinner* culture of this wonderful part of the Finest cuisine at sea from Executive Chef Jacques Pépin world with you. The wines of these FREE Unlimited Internet (one per stateroom) countries are among the best in the Country club-casual ambiance world, and I look forward to Complimentary non-alcoholic beverages throughout the ship showing you how great they can be on this cruise.” *Ask how this can be upgraded to the All Inclusive Drink package onboard. -

Population Analysis and Community Workshop for Far Eastern Curlew Conservation Action in Pantai Cemara, Desa Sungai Cemara – Jambi

POPULATION ANALYSIS AND COMMUNITY WORKSHOP FOR FAR EASTERN CURLEW CONSERVATION ACTION IN PANTAI CEMARA, DESA SUNGAI CEMARA – JAMBI Final Report Small Grant Fund of the EAAFP Far Eastern Curlew Task Force Iwan Febrianto, Cipto Dwi Handono & Ragil S. Rihadini Jambi, Indonesia 2019 The aim of this project are to Identify the condition of Far Eastern Curlew Population and the remaining potential sites for Far Eastern Curlew stopover in Sumatera, Indonesia and protect the remaining stopover sites for Far Eastern Curlew by educating the government, local people and community around the sites as the effort of reducing the threat of habitat degradation, habitat loss and human disturbance at stopover area. INTRODUCTION The Far Eastern Curlew (Numenius madagascariencis) is the largest shorebird in the world and is endemic to East Asian – Australian Flyway. It is one of the Endangered migratory shorebird with estimated global population at 38.000 individual, although a more recent update now estimates the population at 32.000 (Wetland International, 2015 in BirdLife International, 2017). An analysis of monitoring data collected from around Australia and New Zealand (Studds et al. in prep. In BirdLife International, 2017) suggests that the species has declined much more rapidly than was previously thought; with an annual rate of decline of 0.058 equating to a loss of 81.7% over three generations. Habitat loss occuring as a result of development is the most significant threat currently affecting migratory shorebird along the EAAF (Melville et al. 2016 in EAAFP 2017). Loss of habitat at critical stopover sites in the Yellow Sea is suspected to be the key threat to this species and given that it is restricted to East Asian - Australasian Flyway, the declines in the non-breeding are to be representative of the global population. -

Hudsonian Godwit (Limosa Haemastica) at Orielton Lagoon, Tasmania, 09/03/2018

Hudsonian Godwit (Limosa haemastica) at Orielton Lagoon, Tasmania, 09/03/2018 Peter Vaughan and Andrea Magnusson E: T: Introduction: This submission pertains to the observation and identification of a single Hudsonian Godwit (Limosa haemastica) at Orielton Lagoon, Tasmania, on the afternoon of the 9th of March 2018. The bird was observed in the company of 50 Bar-tailed Godwits (Limosa lapponica) and a single Black-tailed Godwit (Limosa limosa), and both comparative and diagnostic features were used to differentiate it from these species. Owing to the recognised difficulties in differentiating similar species of wading birds, this submission makes a detailed analysis of the features used to identify the godwit in question. If accepted, this sighting would represent the eighth confirmed record of this species in Australia, and the second record of this species in Tasmania. Sighting and Circumstances: The godwit in question was observed on the western side of Orielton Lagoon in Tasmania, at approximately 543440 E 5262330 N, GDA 94, 55G. This location is comprised of open tidal mudflats abutted by Sarcicornia sp. saltmarsh, and is a well- documented roosting and feeding site for Bar-tailed Godwits and several other species of wading bird. This has included, for the past three migration seasons, a single Black-tailed Godwit (extralimital at this location) associating with the Bar-tailed Godwit flock. The Hudsonian Godwit was observed for approximately 37 minutes, between approximately 16:12 and 16:49, although the mixed flock of Bar-tailed Godwits and Black-tailed Godwits was observed for 55 minutes prior to this time. The weather during observation was clear skies (1/8 cloud cover), with a light north- easterly breeze and relatively warm temperatures (wind speed nor exact temperature recorded). -

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List The target species list (species to be surveyed) should not change over the course of the study, therefore determining the target species list is an important project design task. Because waterbirds, including shorebirds, can occur in very high numbers in a census area, it is often not possible to count all species without compromising the quality of the survey data. For the basic shorebird census program (protocol 1), we recommend counting all shorebirds (sub-Order Charadrii), all raptors (hawks, falcons, owls, etc.), Common Ravens, and American Crows. This list of species is available on our field data forms, which can be downloaded from this site, and as a drop-down list on our online data entry form. If a very rare species occurs on a shorebird area survey, the species will need to be submitted with good documentation as a narrative note with the survey data. Project goals that could preclude counting all species include surveys designed to search for color-marked birds or post- breeding season counts of age-classed bird to obtain age ratios for a species. When conducting a census, you should identify as many of the shorebirds as possible to species; sometimes, however, this is not possible. For example, dowitchers often cannot be separated under censuses conditions, and at a distance or under poor lighting, it may not be possible to distinguish some species such as small Calidris sandpipers. We have provided codes for species combinations that commonly are reported on censuses. Combined codes are still species-specific and you should use the code that provides as much information as possible about the potential species combination you designate. -

The Systematic Position of the Surfbird, Aphriza Virgata

THE SYSTEMATIC POSITION OF THE SURFBIRD, APHRIZA VIRGATA JOSEPH R. JEHL, JR. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104 The taxonomic relationships of the Surfbird, ( 1884) elevated the tumstone-Surfbird unit Aphriza virgata, have long been one of the to family rank. But, although they stated (p. most controversial problems in shorebird clas- 126) that Aphrizu “agrees very closely” with sification. Although the species has been as- Arenaria, the only points of similarity men- signed to a monotypic family (Shufeldt 1888; tioned were “robust feet, without trace of web Ridgway 1919), most modern workers agree between toes, the well formed hind toe, and that it should be placed with the turnstones the strong claws; the toes with a lateral margin ( Arenaria spp. ) in the subfamily Arenariinae, forming a broad flat under surface.” These even though they have reached no consensuson differences are hardly sufficient to support the affinities of this subfamily. For example, familial differentiation, or even to suggest Lowe ( 1931), Peters ( 1934), Storer ( 1960), close generic relationship. and Wetmore (1965a) include the Arenariinae Coues (1884605) was uncertain about the in the Scolopacidae (sandpipers), whereas Surfbirds’ relationships. He called it “a re- Wetmore (1951) and the American Ornithol- markable isolated form, perhaps a plover and ogists ’ Union (1957) place it in the Charadri- connecting this family with the next [Haema- idae (plovers). The reasons for these diverg- topodidae] by close relationships with Strep- ent views have never been stated. However, it silas [Armaria], but with the hind toe as well seems that those assigning the Arenariinae to developed as usual in Sandpipers, and general the Charadriidae have relied heavily on their appearance rather sandpiper-like than plover- views of tumstone relationships, because schol- like. -

Purple Sandpiper

Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision Report Date: January 13, 2016 Calidris maritima (Purple Sandpiper) Priority 1 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) Class: Aves (Birds) Order: Charadriiformes (Plovers, Sandpipers, And Allies) Family: Scolopacidae (Curlews, Dowitchers, Godwits, Knots, Phalaropes, Sandpipers, Snipe, Yellowlegs, And Woodcock) General comments: Recent surveys suggest population undergoing steep population decline within 10 years. IFW surveys conducted in 2014 suggest population declined by 49% since 2004 (IFW unpublished data). Maine has high responsibility for wintering population, regional surveys suggest Maine may support over 1/3 of the Western Atlantic wintering population. USFWS Region 5 and Canadian Maritimes winter at least 90% of the Western Atlantic population. Species Conservation Range Maps for Purple Sandpiper: Town Map: Calidris maritima_Towns.pdf Subwatershed Map: Calidris maritima_HUC12.pdf SGCN Priority Ranking - Designation Criteria: Risk of Extirpation: NA State Special Concern or NMFS Species of Concern: NA Recent Significant Declines: Purple Sandpiper is currently undergoing steep population declines, which has already led to, or if unchecked is likely to lead to, local extinction and/or range contraction. Notes: Recent surveys suggest population undergoing steep population decline within 10 years. IFW surveys conducted in 2014 suggest population declined by 49% since 2004 (IFW unpublished data). Maine has high responsibility for wintering populat Regional Endemic: Calidris maritima's global geographic range is at least 90% contained within the area defined by USFWS Region 5, the Canadian Maritime Provinces, and southeastern Quebec (south of the St. Lawrence River). Notes: Recent surveys suggest population undergoing steep population decline within 10 years. IFW surveys conducted in 2014 suggest population declined by 49% since 2004 (IFW unpublished data). -

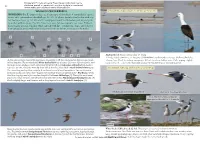

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

Biogeographical Profiles of Shorebird Migration in Midcontinental North America

U.S. Geological Survey Biological Resources Division Technical Report Series Information and Biological Science Reports ISSN 1081-292X Technology Reports ISSN 1081-2911 Papers published in this series record the significant find These reports are intended for the publication of book ings resulting from USGS/BRD-sponsored and cospon length-monographs; synthesis documents; compilations sored research programs. They may include extensive data of conference and workshop papers; important planning or theoretical analyses. These papers are the in-house coun and reference materials such as strategic plans, standard terpart to peer-reviewed journal articles, but with less strin operating procedures, protocols, handbooks, and manu gent restrictions on length, tables, or raw data, for example. als; and data compilations such as tables and bibliogra We encourage authors to publish their fmdings in the most phies. Papers in this series are held to the same peer-review appropriate journal possible. However, the Biological Sci and high quality standards as their journal counterparts. ence Reports represent an outlet in which BRD authors may publish papers that are difficult to publish elsewhere due to the formatting and length restrictions of journals. At the same time, papers in this series are held to the same peer-review and high quality standards as their journal counterparts. To purchase this report, contact the National Technical Information Service, 5285 Port Royal Road, Springfield, VA 22161 (call toll free 1-800-553-684 7), or the Defense Technical Infonnation Center, 8725 Kingman Rd., Suite 0944, Fort Belvoir, VA 22060-6218. Biogeographical files o Shorebird Migration · Midcontinental Biological Science USGS/BRD/BSR--2000-0003 December 1 By Susan K. -

The First Record of Common Ringed Plover (Charadrius Hiaticula) in British Columbia

The First Record of Common Ringed Plover (Charadrius hiaticula) in British Columbia. By Rick Toochin. Submitted: April 15, 2019. Introduction and Distribution The Common Ringed Plover (Charadrius hiaticula) is a widespread Old World shorebird species that is found breeding in the Arctic and subarctic regions from Greenland, Europe, east to Siberia (O’Brien et al. 2006). In North America, this species breeds on Baffin Island, eastern Ellesmere Island (Godfrey 1986). The Common Ringed Plover winters primarily from Western Europe, the Mediterranean Basin, throughout Africa, including Madagascar, and the Middle East (Hayman et al. 1986, O’Brien et al. 2006, Brazil 2009). There are three recognized subspecies of the Common Ringed Plover (Thies et al. 2018). Distinction between the subspecies is based on moult; with features changing clinally North to South, rather than East to West, making it impossible to draw a dividing line in Northwestern Europe (del Hoyo et al. 1996, Snow and Perrins 1998). The nominate subspecies of Common Ringed Plover is (C. h. hiaticula ) which breeds from southern Scandinavia to Great Britain, and northwestern France (Wiersma et al. 2019). This subspecies winters from Great Britain, south into Africa (del Hoyo et al. 1996, Snow and Perrins 1998). The second subspecies of the Common Ringed Plover is (C. h. tundrae) which is found breeding from northern Scandinavia, and northern Russia east to the Chukotskiy Peninsula, and is a casual breeder also in the northern Bering Sea region of Alaska on St Lawrence Island (Wiersma et al. 2019). This subspecies winters in the Caspian Sea region, and from Southwest Asia, south and east to South Africa (Wiersma et al.