The Salience of Ethnic Categories: Field and Natural Experimental

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maleru (ಮಲ ೇರು माले셁) Mystery Resolved

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 20, Issue 5, Ver. V (May. 2015), PP 06-27 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Scheduling of Tribes: Maleru (ಮಲ ೇರು माले셁) Mystery Resolved V.S.Ramamurthy1 M.D.Narayanamurthy2 and S.Narayan3 1,2,3(No 422, 9th A main, Kalyananagar, Bangalore - 560043, Karnataka, India) Abstract: The scheduling of tribes of Mysore state has been done in 1950 by evolving a list of names of communities from a combination of the 1901 Census list of Animist-Forest and Hill tribes and V.R.Thyagaraja Aiyar's Ethnographic glossary. However, the pooling of communites as Animist-Forest & Hill tribes in the Census had occurred due to the rather artificial classification of castes based on whether they were not the sub- caste of a main caste, their occupation, place of residence and the fictitious religion called ‘Animists’. It is not a true reflection of the so called tribal characteristics such as exclusion of these communities from the mainstrream habitation or rituals. Thus Lambáni, Hasalaru, Koracha, Maleru (Máleru ಮಲ ೇರು माले셁‘sic’ Maaleru) etc have been categorized as forest and hill tribes solely due to the fact that they neither belonged to established castes such as Brahmins, Vokkaligas, Holayas etc nor to the occupation groups such as weavers, potters etc. The scheduling of tribes of Mysore state in the year 1950 was done by en-masse inclusion of some of those communities in the ST list rather than by the study of individual communities. -

Gives Edge to BJP in Karnataka

VERDICT 2019 Sparring between Congress and JD (S) Gives Edge to BJP in Karnataka S. RAJENDRAN A para-motor flying in Vijayapura city on Monday, May 8, 2019, to encourage people to vote in coming Lok Sabha elections. Photo: Rajendra Singh Hajeri. For long a pocket borough of the Congress party Karnataka appears headed for a waveless election. The southern State, which goes to the polls in two phases - 14 seats each on April 18 and April 23, will see a direct contest between the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which is in government in the centre and the Congress-Janata Dal (Secular) combine, which is in power at the State. S. Rajendran, Senior Fellow, The Hindu Centre for Politics and Public Policy, Bengaluru, writes on how each of the main parties to the contest are placed. The two main contestents - the BJP and the Congress-JD (S) coalition, he says, are expected to share the spoils, though the former enjoys an edge. he 2019 General Election to the Lok Sabha for the 28 seats from Karnataka, to be held in two phases on April 18 and 23 (See Appendix for T dates and constituencies1), is expected to be markedly different from the last elections held in 2014. First, this time round the poll will be a direct challenge between the Congress-Janata Dal (Secular) [JD (S)] combine and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Second, there is no perceptible wave in favour of any political party. The two formations are, therefore, expected to share the spoils although the BJP enjoys considerable edge because of two factors: differences within the Congress party and the conflict of interests between the grassroots level workers of the Congress and the JD (S). -

Community List

ANNEXURE - III LIST OF COMMUNITIES I. SCHEDULED TRIB ES II. SCHEDULED CASTES Code Code No. No. 1 Adiyan 2 Adi Dravida 2 Aranadan 3 Adi Karnataka 3 Eravallan 4 Ajila 4 Irular 6 Ayyanavar (in Kanyakumari District and 5 Kadar Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 6 Kammara (excluding Kanyakumari District and 7 Baira Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 8 Bakuda 7 Kanikaran, Kanikkar (in Kanyakumari District 9 Bandi and Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 10 Bellara 8 Kaniyan, Kanyan 11 Bharatar (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 9 Kattunayakan Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 10 Kochu Velan 13 Chalavadi 11 Konda Kapus 14 Chamar, Muchi 12 Kondareddis 15 Chandala 13 Koraga 16 Cheruman 14 Kota (excluding Kanyakumari District and 17 Devendrakulathan Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 18 Dom, Dombara, Paidi, Pano 15 Kudiya, Melakudi 19 Domban 16 Kurichchan 20 Godagali 17 Kurumbas (in the Nilgiris District) 21 Godda 18 Kurumans 22 Gosangi 19 Maha Malasar 23 Holeya 20 Malai Arayan 24 Jaggali 21 Malai Pandaram 25 Jambuvulu 22 Malai Vedan 26 Kadaiyan 23 Malakkuravan 27 Kakkalan (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 24 Malasar Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 25 Malayali (in Dharmapuri, North Arcot, 28 Kalladi Pudukkottai, Salem, South Arcot and 29 Kanakkan, Padanna (in the Nilgiris District) Tiruchirapalli Districts) 30 Karimpalan 26 Malayakandi 31 Kavara (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 27 Mannan Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 28 Mudugar, Muduvan 32 Koliyan 29 Muthuvan 33 Koosa 30 Pallayan 34 Kootan, Koodan (in Kanyakumari District and 31 Palliyan Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 32 Palliyar 35 Kudumban 33 Paniyan 36 Kuravan, Sidhanar 34 Sholaga 39 Maila 35 Toda (excluding Kanyakumari District and 40 Mala Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 41 Mannan (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 36 Uraly Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 42 Mavilan 43 Moger 44 Mundala 45 Nalakeyava Code III (A). -

Myths and Beliefs on Sacred Groves Among Kembatti Communities: a Case Study from Kodagu District, South-India

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH CULTURE SOCIETY ISSN: 2456-6683 Volume - 1, Issue - 10, Dec – 2017 UGC Approved Monthly, Peer-Reviewed, Refereed, Indexed Journal Impact Factor: 3.449 Publication Date: 31/12/2017 Myths and beliefs on sacred groves among Kembatti communities: A case study from Kodagu District, South-India Goutham A M.1, Annapurna M 2 1Research Scholar, Department of Studies in Anthropology, University of Mysore, Manasagangothri, Mysore, India 2Professor, Department of Studies in Anthropology(Rtd), University of Mysore, Manasagangothri, Mysore, India Email – [email protected] Abstract: Sacred groves are forest patches of pristine vegetation left untouched by the local inhabitants for centuries in the name of deities, related socio-cultural beliefs and taboos. Though the different scientists defined it from various points of view, the central idea or the theme of sacred grove remains the same. Conservation of natural resources through cultural and religious beliefs has been the practice of diverse communities in India, resulting in the occurrence of sacred groves all over the country. Though they are found in all bio-geographical realms of the country, maximum number of sacred groves is reported from Western Ghats, North East India and Central India. In Karnataka, sacred groves are known by many local names such as: Devarakadu, Kaan forest, Siddaravana, Nagabana, Bana etc. This paper gives detailed insight on sacred groves of kodagu District of Karnataka. Indigenous communities like Kembatti Holeyas and Kudiyas defined them as ‘tracts of virgin forest that were left untouched, harbour rich biodiversity, and are protected by the local people due to their cultural and religious beliefs and taboos that the deities reside in them and protect the villagers from different calamities’. -

Fertility Transition: the Case of Rural Communities in Karnataka, India

FERTILITY TRANSITION: THE CASE OF RURAL COMMUNITIES IN KARNATAKA, INDIA. T.V.Sekher Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore, India. Abstract Most developing societies are now experiencing demographic transition at varying levels. In a vast country like India with high demographic diversity and heterogeneity, the levels and stages of fertility decline differ significantly from state to state. Given this situation, it is interesting to have a look at demographic transition in South India ( a population of 220 million in 2001), which has now entered its last phase with fertility rates registering significant decline during the last two decades well ahead of other parts of the country. However, in view of the average level of economic development in this part of the country, the South Indian experience has revived discussions on the determinants of fertility reduction, notably about the respective role played by endogenous (cultural and historical features) and exogenous (economic transformations and governmental interventions) factors in popularizing family planning. The present paper has aimed at understanding the channels of fertility decline in the South Indian State of Karnataka through an analysis of socio-cultural and spatial differentials. It has also attempted to capture the self- sustaining nature of fertility reduction by bringing out the fact that fertility decline in one social group is fuelled by low fertility behaviour in other groups. For this purpose, three village studies were carried out by employing focus group discussions and individual case studies to gather qualitative data from different social groups.It was observed that villagers were trying to cope with new 'risk factors ' by modifying their behaviour, and one among them was the fertility behaviour. -

Linguistic Anthropology, Sociolinguistics and Language Teaching

FACULTY PROFILE 1. Name: Dr. Ravindranath, B. K Photo 2. Designation: Professor 3. Qualification: M.A, (Ling),M.A,(Anthro) PGDS, PGDL, Ph.D., 4. Area of Specialization: Linguistic anthropology, Sociolinguistics and Language teaching. 5. Awarded Junior/Senior Research Fellowship From Anthropological Survey of India, Southern Regional Centre, Mysore and Engaged in the National Project „People of India‟ (1987 – 1990) PUBLICATIONS: 1. Ravindranath, B. K. (2000). Devadiga. In K.S. Singh (Ed.), People of India: Karnataka, (Volume XXVI, Part one, pp. 361-365). Affiliated East-West Press Pvt.Ltd. New Delhi 110001. ISBN 81-85938-98-9 2. Ravindranath, B. K. (2000). Kalanady. In K.S. Singh (Ed.), People of India: Karnataka, (Volume XXVI, Part one, pp. 536-540). Affiliated East-West Press Pvt.Ltd. New Delhi 110001. ISBN 81-85938-98-9 3. Ravindranath, B. K. (2000). Karimpalan (SC). In K.S. Singh (Ed.), People of India: Karnataka, (Volume XXVI, Part one, pp. 583-587). Affiliated East-West Press Pvt.Ltd. New Delhi 110001. ISBN 81-85938-98-9 4. Ravindranath, B. K. (2000). Kidaran. In K.S. Singh (Ed.), People of India: Karnataka, (Volume XXVI, Part one, pp. 606-611). Affiliated East-West Press Pvt.Ltd. New Delhi 110001. ISBN 81-85938-98-9 5. Ravindranath, B. K. (2000). Koraga (ST). In K.S. Singh (Ed.), People of India: Karnataka, (Volume XXVI, Part one, pp. 652-657). Affiliated East-West Press Pvt.Ltd. New Delhi 110001. ISBN 81-85938-98-9 6. Ravindranath, B. K. (2000). Kunduvadian. In K.S. Singh (Ed.), People of India: Karnataka, (Volume XXVI, Part one, pp. -

July 2021.Pmd

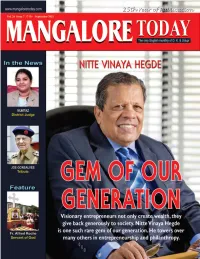

MANGALORE TODAY - SEPTEMBER 2021 1 2 MANGALORE TODAY - SEPTEMBER 2021 PPPOWER POINT PICTURE OF THE MONTH Hands-on Experience! Union Minister of State for Agriculture and Farmers' Welfare Shobha Karandlaje joins farmers in cultivating a fallow land at Kadekar village in Udupi as part of Hadilu Bhoomi Revival Scheme. ““““““ WWWORDSWORTH ”””””” “We must break the walls of “The musical world has caste, religion, superstitions the immense power to as well as mistrust that attract lakhs of people as create impediments in the music plays a very key role path of our progress” in enlivening our minds Prof Sabeeha B.Gowda, Professor, Dept of and hearts” Kannada Studies of Mangalore University at noted singer Ajay Warrior at the inaurual of a farewell ceremony on the occasion of her “Knowledge of local Karavali Music Camp in Mangaluru. retirement from service. languages will go a long way in assisting the police “Ranga Mandiras need to be “Man can lead a peaceful to efficiently maintain law protected if we have to life when he incorporates and order as well as in preserve and promote the good values and shuns his investigation of crimes” theatrical field” ego” City Police Commissioner N Shashi eminent Kannada movie director Rajendra Prof. P S Yadapadittaya, Vice Chancellor of Kumar at the inaugural of the month Singh Babu while launching the fund raising Mangalore University at the Kanaka lecture long Tulu learning workshop for police drive for the renovation of Don Bosco Hall in series at the University. officers and personnel. Mangaluru. MANGALORE TODAY - SEPTEMBER 2021 3 EEEDITOR’’’SSS EDGE VOL 24 ISSUE 7 SEPTEMBER 2021 Publisher and Editor V. -

Newsletter July-December 2011

Vol. 18 July-December 2011 No. 2 Taking a periodic review of the activities in the Institute helps in understanding the direction and pace of academic work as well as identifying the problem areas to be tackled in the course of development of the Institute. This exercise should not be taken as a routine drill but it should provide us a path for comparative understanding of our own accomplishments and shortfalls. I am happy that during the past six months, the activities in the Institute have sustained the earlier pace and pattern. An important task of faculty evaluation has been completed satisfactorily and provided good inputs for the faculty members and the Board of Governors. All the faculty colleagues cooperated and participated in the process of evaluation wholeheartedly and, I hope, they were able to pick up a few threads to move further towards excellence. I am quite pleased to record here the activities undertaken in the past six months with a sense of fulfillment, happiness as well as to kindle our thinking for future. From the During the last six months, the faculty and staff of the Institute were busy with a number Director’s Desk . of seminars, research projects and other academic activities. In this period, we organised 22 seminars at the Institute, averaging almost three events a month. These were attended by the faculty members as also invitees from outside. There were eight important events including a Training Programme in Econometrics for officers belonging to Indian Statistical Services; an International Post-Graduate Course on ‘Approaching the Environment in India – Issues and Methods in the Study of the Nature-Economy-Society Interface’ for the students from Nordic I am satisfied with this countries; another Training Workshop organised jointly with the University of Groningen, pace… but that does the Netherlands, on ‘Qualitative Data Analysis on Population Studies’. -

Madiga's Traditional Food Culture and Lifestyle

www.ijcrt.org © 2018 IJCRT | Volume 6, Issue 1 January 2018 | ISSN: 2320-2882 MADIGA’S TRADITIONAL FOOD CULTURE AND LIFESTYLE Dr.Jayaram Gollapudi Department of A.I.H.C & Archaeology Osmania University –Hyderabad Telangana; India -500007 Why the people of Madigas are used dry food, the Madigas almost daily food hunters from the century’s, the Madiga people closely related natural resources. Madigas traditionally lived in hamlets outside mainstream village life. By the twentieth century both British administration and Nizam’s administration began to employ them as village messengers. Madigas lived by tanning the leather and it was the “duty” of the Madiga family to provide chappals and other leather goods to the upper caste families with whom they were tied. Madigas contributed a lot to the music and dance. life system started Madiga with the marriages are contracted by negotiation among the Madigas and its allied castes. This is the only type in existence3 in these castes. Marriage with the following relatives is preferred among these castes (i) mother’s brother’s daughter, (ii) father’s sister’s daughter. Except the Madigas of Rayalaseema regions all regions, all others including the allied castes accept own sister’s daughter also in marriage. One can also marry his brother’s wife’s younger sister. Marriage is exogamous, i.e. marriage will not be contracted among the people of same intiperu. The custom of child betrothal exists. Key words: Culture, Life Style, Jambhava, Lord Shiva, Jwohari, Ornaments, Tattoos. The origin for the Jazz drums comes from the primitive but exact rhythm and beat producing “Thappeta” tanned skins covered on the wooden round frames and were played by beating them with two sticks. -

Caste Politics and State Integration: a Case Study of Mysore State

MAHESH RAMASWAMY, ASHA S. Caste Politics and State Integration... 195 DOI: 10.1515/ijas-2015-0009 MAHESH RAMASWAMY DVS EVENING COLLEGE ASHA. S GOVERNMENT FIRST GRADE COLLEGE Caste Politics and State Integration: a Case Study of Mysore State Abstract: The subject of unifi cation is as vibrant as national movement even after 58 years of a fractured verdict. More than to achieve a physical conjugation it was an attempt for cultural fusion. The aspiration for linguistic unifi cation was a part of the national discourse. The movement, which began with mystic originations, later on turned out to become communal. Political changes during 1799 A.D. and 1857 A.D. changed the fortunes of Mysore state and ultimately led to its disintegration and became the reason for this movement. The concept of unifi cation is akin to the spirit of nationalism, against the background of colonial regime assigning parts of land to different administrative units without taking into consideration the historical or cultural aspects of that place. Kannadigas marooned in multi lingual states experient an orphaned situation got aroused with the turn of nineteenth century. The problem precipitated by the company was diluted by British when they introduced English education. Though the positive aspect like emergence of middle class is pragmatic, rise of communalism on the other hand is not idealistic. This research paper is designed to examine the polarization of castes during unifi cation movement of Mysore State (Presently called as State of Karnataka, since 1973, which was termed Mysore when integrated) which came into being in 1956 A.D. -

Reservations in India

INTRODUCTION In early September 2001, world television news viewers saw an unusual sight. A delegation from India had come to the United Nations Conference on Racism in Durban, South Africa, not to join in condemnations of Western countries but to condemn India and its treatment of its Dalits (oppressed), as Indians better known abroad as “untouchables” call themselves. The Chairman of India’s official but independent National Human Rights Commission thought the plight of one-sixth of India’s population was worthy of inclusion in the conference agenda, but the Indian government did not agree. India’s Minister of State for External Affairs stated that raising the issue would equate “casteism with racism, which makes India a racist country, which we are not.”1 Discrimination against groups of citizens on grounds of race, religion, language, or national origin has long been a problem with which societies have grappled. Religion, over time, has been a frequent issue, with continuing tensions in Northern Ireland and in Bosnia being but two recent and still smoldering examples. Race-based discrimination in the United States has a long history beginning with evictions of Native Americans by European colonists eager for land and other natural resources and the importation of African slaves to work the land. While the framers of the U.S. Constitution papered over slavery in 1787, it was already a moral issue troubling national leaders, including some Southern slave owners like Washington and Jefferson. On his last political mission, the aging Benjamin Franklin lobbied the first new Congress to outlaw slavery. 1 “Indian Groups Raise Caste Question,” BBC News, September 6, 2001. -

Battles for Bangalore: Reterritorialising the City Janaki Nair Centre for the Study of Culture and Society Bangalore, India

Battles for Bangalore: Reterritorialising the City Janaki Nair Centre for the Study of Culture and Society Bangalore, India A divided city, cleaved by a swathe of parkland and administrative buildings that runs from north west to south east, was united in the single Bangalore City Corporation in 1949.1 No longer did the Bangalore Civil and Military station (referred to as the Cantonment, and the location since 1809 of British troops and their followers), have a separate administration from the old city area. And not just a geographical unity was forged, since the maps of linguistic, cultural and political traditions were redrawn. A previous move to unite the Cantonment, then under the control of the British Resident, with the rest of Princely Mysore was resisted by several cultural and economic groups that had long resided in the Station and enjoyed the perquisites of serving the colonial masters.2 A flurry of petitions protested the proposed "retrocession" of 1935 which would bring the Bangalore Cantonment under the Mysore administration; only the war delayed this move until July 1947.3 By 1949, such petitions were no deterrent to the plans of the new masters. But in the five decades since the formation of the Bangalore corporation, the city's east-west zonation continues to persist, and the uncomfortable question of "independence"4, or at least administrative freedom of the erstwhile cantonment has often been reiterated5. Most frequently, this has been in response to emerging cultural and political movements that seek to reterritorialise the city, refashioning its symbols, monuments or open spaces to evoke other memories, or histories that reflect the triumphs of the nation state, the hopes and aspirations of linguistic nationalisms or of social groups who have long lacked either economic or symbolic capital in the burgeoning city of Bangalore.